Anisocoria

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

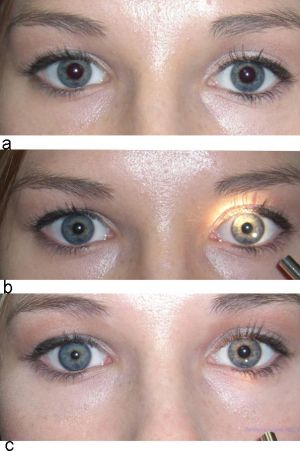

Anisocoria. © 2019 Neuro-ophthalmology Virtual Education Library: NOVEL [1]

Disease Entity

Disease

Anisocoria indicates unequal pupil sizes. It is relatively common, and causes vary from benign physiologic anisocoria to potentially life-threatening emergencies. Thus, thorough clinical evaluation is important for appropriate diagnosis and management of the underlying cause.

Etiology

Generally, anisocoria is caused by impaired dilation (a sympathetic response) or impaired constriction (a parasympathetic response) of pupils. An injury or lesion in either pathway may result in changes in pupil size.

Physiologic (also known as simple or essential) anisocoria is the most common cause of unequal pupil sizes, affecting up to 20% of the population.[2] It is a benign condition with a difference in pupil size of less than or equal to 1 mm.[3] The exact cause is unknown, but it is thought to be due to transient asymmetric supranuclear inhibition of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus that controls the pupillary sphincter.[4] Light and near responses are intact, and the degree of anisocoria is typically equal in light and dark. Physiologic anisocoria may be intermittent, persistent, or even self-resolving.

Congenital anomalies in the structure of the iris may contribute to abnormal pupillary sizes and shapes that present in childhood. Examples include aniridia, coloboma, and ectopic pupil.

Mechanical anisocoria results from damage to the iris or its supporting structures. Causes include physical injury from ocular trauma or surgery, inflammatory conditions such as uveitis, angle-closure glaucoma leading to iris occlusion of the trabecular meshwork, or intraocular tumors causing physical distortion of the iris.

Pharmacologic anisocoria can present as mydriasis or miosis following administration of agents that act on the pupillary dilator or sphincter muscles. Anticholinergics such as atropine, homatropine, tropicamide, scopolamine, and cyclopentolate lead to mydriasis and cycloplegia by inhibiting parasympathetic M3 receptors of the pupillary sphincter and ciliary muscles. Scopolamine patches, glycopyrrolate antiperspirants, nasal vasoconstrictors, and herbals such as jimsonweed, blue nightshade, and angel’s trumpet can dilate pupils.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12] The use of pilocarpine, a nonselective muscarinic receptor agonist in the parasympathetic nervous system, may result in a small and poorly reactive pupil. Sympathomimetics, such as adrenaline, clonidine, and phenylephrine, cause mydriasis through their actions at ɑ1-receptors of the pupillary dilator muscle. Prostaglandins, opioids, and organophosphate insecticides can constrict pupils as well.[6][13][14]

Horner syndrome (oculosympathetic palsy) is classically described by the triad of ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis, although clinical presentations may vary. Anisocoria is greater in the dark due to a defect in the pupillary dilator response secondary to lesions along the sympathetic trunk. Central or first-order lesions are often caused by stroke (may present as lateral medullary syndrome) or demyelinating disease. Preganglionic or second-order neuron lesions may be caused by a Pancoast tumor, mediastinal or thyroid mass, cervical rib, neck trauma, or surgery. Postganglionic or third-order neuron lesions include carotid artery dissection, cavernous sinus lesion, otitis media, and head or neck trauma. Further pharmacologic workup (see Clinical Diagnosis) is useful in confirming Horner syndrome and historically was used to localize the lesion.

Adie tonic pupil results from damage to the parasympathetic ciliary ganglion or short ciliary nerves that innervate the sphincter pupillae and ciliary muscle. Aberrant reinnervation and upregulation of postsynaptic receptors lead to the clinical presentation of a tonically dilated pupil with reaction to near stimulation but poor reaction to light. Ninety percent of cases occur in women between the ages of 20 and 40 years, 80% of cases are unilateral, and 70% of cases are associated with decreased deep tendon reflexes (Adie syndrome).[3] Adie pupil may involve an orbital process, while bilateral cases may indicate systemic processes.[6]

Oculomotor (third) nerve palsy varies in presentation and etiology. The oculomotor nerve innervates 4 extraocular muscles (superior rectus, medial rectus, inferior rectus, and inferior oblique), the sphincter pupillae muscle, the ciliary muscle, and the levator palpebrae muscle. Third nerve palsies rarely present as isolated mydriasis; associated findings include ptosis, an ipsilateral “down and out” gaze, and loss of accommodation. Compressive lesions from head trauma, intracranial aneurysms, uncal herniation, and tumors typically involve the pupil as they affect the superficial parasympathetic fibers that innervate the sphincter pupillae. Ischemic or diabetic oculomotor nerve palsies can spare the pupil.[15]

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias include primary headache disorders that may result in anisocoria, miosis, or ptosis.[6][16] They present with unilateral head pain with ipsilateral autonomic symptoms, such as lacrimation and rhinorrhea.[6]

Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy is a disorder of autoantibodies that target autonomic ganglia.[6][17] It affects sympathetic and parasympathetic systems that may result in pupillary abnormalities, anisocoria, orthostatic hypotension, and anhidrosis.[6][17][18]

Relevant Anatomy

Physiologic control of pupillary function is dictated by sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation to the pupillary dilator and the pupillary sphincter muscles, respectively. Pupillary function is autonomic, largely occurring in response to light stimulation and adrenergic tone.

The sympathetic pathway is a 3-order neuron pathway that mediates pupillary dilation. The first-order neuron originates from the posterolateral hypothalamus and travels caudally down the brainstem to the ciliospinal center of Budge (C8-T2). The second-order neuron continues over the lung apex and synapses at the superior cervical ganglion located at the carotid bifurcation. The third-order neuron ascends within the adventitia of the internal carotid artery wall into the cavernous sinus to ultimately synapses at the pupillary dilator muscle, the Muller muscle of the upper eyelid, and the inferior tarsal muscle of the lower eyelid.

The parasympathetic pathway is a 4-order neuron pathway that controls pupillary constriction and accommodation. Afferent light stimulus is received by retinal ganglion cells whose axons traverse as the optic nerve, optic chiasm, and optic tract to eventually synapse at the pretectal nuclei of the dorsal midbrain at the level of the superior colliculi. The second-order neuron connects each pretectal nucleus to bilateral Edinger-Westphal nuclei in the midbrain, thus allowing for the consensual light reflex. The Edinger-Westphal nucleus then supplies parasympathetic fibers to the third cranial nerve, which traverses the cavernous sinus and enters the orbit via the superior orbital fissure to synapse at the ipsilateral ciliary ganglion. Postganglionic fibers of the short ciliary nerve reach the sphincter pupillae and ciliary muscles.

Diagnosis

History

A careful history to elucidate the onset and chronicity of anisocoria may be useful for determining its etiology. Old photographs can provide information because symptoms may not exist or may go unnoticed. Chronic anisocoria without associated symptoms may point to a benign process such as physiologic anisocoria, whereas sudden-onset anisocoria in the setting of other symptoms may be more worrisome. For example, anisocoria with headaches, confusion, altered mental status, and other focal neurologic deficits suggests an underlying mass effect and may require further neurologic workup and intervention.

A complete ophthalmic history is important because coexisting ocular conditions and previous surgeries or trauma to the head or orbit may contribute to anisocoria. A thorough review of medications, especially any medication with the potential for topical exposure, may provide an explanation for pharmacologic anisocoria. Discussion of exposure to certain narcotics, insecticides (organophosphates), or plants (Brugmansia angel’s trumpet or Datura devil’s trumpet) should also be considered.

Physical Examination

External eye structures should be examined for associated ocular manifestations. Ptosis and gaze deviation may suggest an oculomotor nerve palsy, whereas proptosis may indicate a space-occupying lesion in the orbit.

A thorough pupillary exam is crucial, and it is best done in dim light with the patient’s eyes fixed on a distant object to eliminate the near reaction. Pupils should be compared for size in light and in dark, shape, position, symmetry, and reactivity. The pupils should be evaluated for direct and consensual responses that are normally equal in speed and magnitude. Accommodation to near stimuli should also be examined (ie, to evaluate for light-near dissociation). Impaired light reaction in the setting of a normal near reaction may suggest an Adie tonic pupil or Argyll Robertson pupils of syphilis.

The slit-lamp examination can provide additional information for associated or coexisting ocular conditions. Congenital, traumatic, and surgical causes of anisocoria will often be associated with other structural defects (eg, iris sphincter tears, iris atrophy). The anterior chamber can be examined for signs of uveitis. Abnormal gonioscopy and tonometry findings may suggest angle-closure glaucoma. The clinical picture of Adie tonic pupil under slit-lamp examination shows sectoral iris palsy and vermiform iris movement.[19]

A detailed neurologic exam may help to localize lesions, evaluate for accompanying signs of cranial nerve involvement, and assess for focal neurologic deficits in the sensory, motor, and deep tendon reflex pathways.

Signs and Symptoms

Isolated anisocoria is often asymptomatic, though mydriasis may cause glare, photosensitivity, and impaired accommodation. Presence of pain, headaches, ptosis, diplopia, blurred vision, numbness, weakness, or ataxia may warrant further evaluation for more life-threatening conditions including traumatic injury, intracranial mass, aneurysm, stroke, or carotid dissection.

Clinical Diagnosis

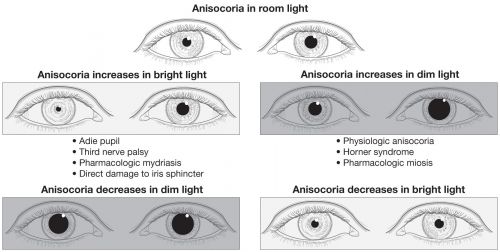

In the diagnostic workup for anisocoria, it is useful to distinguish between anisocoria that is greater in the dark and anisocoria that is greater in the light. This can be followed by a series of pharmacologic tests to further determine the exact etiology.[20]

Anisocoria that is greater in the dark suggests a lesion in the sympathetic pathway, which results in an abnormal pupil that is smaller and unable to dilate in response to removal of a light stimulus. Causes include Horner syndrome, iritis, mechanical anisocoria, and pharmacologic anisocoria from miotics, narcotics, or insecticides.

If Horner syndrome is suspected but the classic triad is not present, then 1 to 2 drops (separated by 5 minutes) of 4%-10% cocaine can be administered to both eyes with re-evaluation after 30 to 45 minutes. Cocaine prevents the reuptake of norepinephrine at the postsynaptic third-order neuron, resulting in dilation of the normal pupil but no movement of the Horner pupil. Therefore, in the presence of Horner syndrome, there is an increase in pupillary asymmetry after cocaine instillation. Apraclonidine, a strong α2- and weak α1-agonist, is a more readily available alternative to cocaine. Although 0.5%-1% apraclonidine causes constriction of the normal pupil due to its strong α2-adrenergic activity, it causes reversal of anisocoria in a Horner pupil by moderately dilating the affected pupil that has denervation supersensitivity (when supersensitivity is present, apraclonidine’s weak α1-agonist activity predominates).[21] Importantly, apraclonidine use is contraindicated in young children, so cocaine is the appropriate choice in these cases.

In addition, 1% hydroxyamphetamine (Paredrine) can be used to localize the lesion in Horner syndrome. Hydroxyamphetamine requires an intact third-order sympathetic neuron to stimulate norepinephrine release. Therefore, an asymmetric dilation suggests a third-order or postganglionic lesion, whereas equal pupillary dilation indicates a central or preganglionic lesion.[23] Pharmacologic localization may be challenging because it is recommended that hydroxyamphetamine be administered 48 hours following apraclonidine or cocaine due to possible false-positive and false-negative rates.[6][23][24] In cases of acute Horner syndrome, it is appropriate to proceed to imaging without pharmacologic lesion localization.

On the other hand, anisocoria that is greater in the light suggests a parasympathetic defect, resulting in an abnormal pupil that is larger and unable to constrict in response to a light stimulus. Causes include Adie tonic pupil, oculomotor nerve palsy, mechanical issues, or pharmacologic dilation from mydriatics/cycloplegics (atropine, tropicamide, cyclopentolate), cocaine, or other pharmacologic agents like scopolamine (eg, exposure from use of a scopolamine patch for nausea/motion sickness) or glycopyrronium (eg, exposure from use of glycopyrronium wipes for treatment of hyperhidrosis).

The use of pilocarpine can be diagnostic in this setting. Low doses of 0.1%-0.125% pilocarpine or 2.5% methacholine do not constrict a normal pupil but result in constriction of an Adie tonic pupil due to hypersensitivity from the upregulation of cholinergic receptors. If no constriction is observed, a higher dose of 1% pilocarpine is used. Pupillary constriction suggests an oculomotor nerve palsy, whereas no response indicates a pharmacologic cause to the anisocoria. Notably, as already mentioned, oculomotor palsy presenting as isolated anisocoria would be exceedingly rare.

Diagnostic Procedures

Imaging of the head, neck, and chest can help identify causes of Horner syndrome or oculomotor nerve palsies when pharmacologic tests are equivocal or clinical suspicion persists for an underlying aneurysm, dissection, stroke, or tumor.

Management

The most important step in managing anisocoria is evaluating for dangerous underlying causes (ie, posterior communicating artery aneurysm causing a third nerve palsy, internal carotid dissection causing a Horner syndrome, acute angle closure causing iris ischemia) and if any are present, proceeding with appropriate treatment of the underlying condition. In and of itself, anisocoria is often asymptomatic and often does not require intervention. Mechanical anisocoria secondary to trauma may require surgery to correct the structural defect. Mechanical anisocoria secondary to other ophthalmic conditions such as uveitis or acute-angle glaucoma can be medically and/or surgically managed as indicated. Pharmacologic anisocoria typically resolves with cessation of the offending agent. Benign causes of Horner syndrome and oculomotor nerve palsy can be observed. Consultation with a neurologist or neuro-ophthalmologist is recommended for atypical cases, such as autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.[6] However, life-threatening causes such as stroke, aneurysm, hemorrhage, dissection, and tumor must be ruled out and/or managed appropriately.

Additional Resources

- Anisocoria. North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society. Patient Brochures for Patients. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.nanosweb.org/anisocoria

- Boyd K. What is anisocoria? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye Health. September 9, 2024. Accessed June 18, 2025. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-anisocoria

References

- ↑ Lee, AG. Anisocoria. Neuro-ophthalmology Virtual Education Library: NOVEL. Web Site Available at https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6cc5cm7 Accessed March 24, 2022. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

- ↑ Lam BL, Thompson HS, Corbett JJ. The prevalence of simple anisocoria. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104(1):69-73.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kaiser PK, Friedman NJ. The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology. 4th ed. Saunders; 2014:647.

- ↑ Loewenfeld IE. "Simple, central" anisocoria: a common condition, seldom recognized. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;83(5):832-839.

- ↑ Pharmacologic miosis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed June 18, 2025. https://www.aao.org/education/image/pharmacologic-miosis-2

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Gross JR, McClelland CM, Lee MS. An approach to anisocoria. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27(6):486-492.

- ↑ Moeller JJ, Maxner CE. The dilated pupil: an update. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7(5):417-422.

- ↑ Firestone D, Sloane C. Not your everyday anisocoria: Angel's trumpet ocular toxicity. J Emerg Med. 2007;33(1):21-24.

- ↑ Izadi S, Choudhary A, Newman W. Mydriasis and accommodative failure from exposure to topical glycopyrrolate used in hyperhidrosis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26(3):232-233.

- ↑ Thompson HS. Cornpicker's pupil: Jimson weed mydriasis. J Iowa Med Soc. 1971;61(8):475-477.

- ↑ Rubinfeld RS, Currie JN. Accidental mydriasis from blue nightshade "lipstick." J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1987;7(1):34-37.

- ↑ Thiele EA, Riviello JJ. Scopolamine patch-induced unilateral mydriasis. Pediatrics. 1995;96(3 Pt 1):525.

- ↑ Slattery A, Liebelt E, Gaines LA. Common ocular effects reported to a poison control center after systemic absorption of drugs in therapeutic and toxic doses. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(6):519-523.

- ↑ Dinslage S, Diestelhorst M, Kuhner H, Krieglstein GK. The effect of latanoprost 0.005% on pupillary reaction of the human eye. Ophthalmologe. 2000;97(6):396-401.

- ↑ Goldstein JE, Cogan DG. Diabetic ophthalmoplegia with special reference to the pupil. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960;64:592-600.

- ↑ May A. Diagnosis and clinical features of trigemino-autonomic headaches. Headache. 2013;53(9):1470-1478.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nakane S, Higuchi O, Koga M, et al. Clinical features of autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy and the detection of subunit-specific autoantibodies to the ganglionic acetylcholine receptor in Japanese patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118312.

- ↑ Li Y, Jammoul A, Mente K, et al. Clinical experience of seropositive ganglionic acetylcholine receptor antibody in a tertiary neurology referral center. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52(3):386-391.

- ↑ Thompson HS. Segmental palsy of the iris sphincter in Adie's syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96(9):1615-1620.

- ↑ Thompson HS, Pilley SFJ. Unequal pupils. A flow chart for sorting out the anisocorias. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976;21(1):45-48.

- ↑ Koc F, Kavuncu S, Kansu T, Acaroglu G, Firat E. The sensitivity and specificity of 0.5% apraclonidine in the diagnosis of oculosympathetic paresis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(11):1442-1444.

- ↑ Anisocoria. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed June 18, 2025. https://www.aao.org/education/image/anisocoria-2

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Cremer SA, Thompson HS, Digre KB, Kardon RH. Hydroxyamphetamine mydriasis in Horner's syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(1):71-76.

- ↑ Van der Wiel HL, Van Gijn J. Localization of Horner's syndrome. Use and limitations of the hydroxyamphetamine test. J Neurol Sci. 1983;59(2):229-235.