Ocular Rosacea

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Background

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory acneiform skin condition that primarily affects the centrofacial and periocular regions. Most frequently found in patients 30-60 years old and is up to three times more common in women. According to the National Rosacea Society estimates, 16 million Americans suffer from acne rosacea, and 58%–72% of rosacea patients develop ophthalmic findings. There are four distinct subtypes, with type IV being ocular rosacea.[2] The hallmarks of ocular rosacea include bilateral chronic blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction, and chronic scarring. There are subsequent tear film instability and debris, tearing, discomfort, photophobia, keratitis, and blurred vision. Some patients also develop recurrent chalazia secondary to meibomian gland dysfunction.[3] Symptomatically patients may complain of burning and foreign body sensation.[4] Left untreated, recurrent episodes can lead to peripheral corneal ulceration, corneal scarring , and neovascularization.

Disease Entity

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory acneiform skin condition that leads to erythema of the skin on the face and neck. It can frequently involve the eyes with studies showing ocular involvement in 6 to 58% of patients. It is characterized by a malar rash, which can include papules and pustules on the face and neck. The hallmarks of ocular rosacea include bilateral chronic blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. At the slit lamp, eyelid margin telangiectasia, and inspissation of the meibomian glands are seen. Patients frequently develop evaporative dry eye. Some patients develop recurrent chalazia. Symptomatically patients may complain of burning and foreign body sensation. Left untreated, recurrent episodes can lead to peripheral corneal ulceration, corneal scarring, and neovascularization.[5]

Pathophysiology

Rosacea is thought to be an inflammatory condition with altered immune system responses and vascular dysregulation. Patients with ocular rosacea have abnormally enhanced sensitivity to common environmental stimuli, such as sun exposure, extremes of weather, spicy foods, heated beverages, emotional stress, strenuous exercise, alcohol and caffeine consumption (vasodilatory effects), certain cosmetics, medications (amiodarone, niacin, beta blockers, topical steroids, nasal steroids), high doses of vitamins B6 and B12, and dairy products.[4] These factors contribute to activation of the inflammatory response and immune system, which expresses an enhanced level of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in the epidermis. Upregulated TLR2 in keratinocytes leads to an increase in activity of an enzyme serine protease, KLK5, which has a role in cathelicidin production. Cathelicidin in turn causes an increase in the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) level in epidermal keratinocytes leading to vascular endothelial changes and angiogenesis. Its corneal effects include increased matrix metalloproteinase production by corneal stromal fibroblasts and epithelial cells.[3]

Additional sources of inflammation include elevated levels of interleukin-1a and b, gelatinase B (metalloproteinase-9) and collagenase-2 (MMP-8) in the tear fluids of patients with ocular rosacea. Elevated serum level of Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alfa) and overexpression of ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) and HLA-DR in conjunctival epithelial cells of these patients is also observed.[3]

Etiology

Acne rosacea, commonly known simply as rosacea, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that primarily affects the central face. Its exact cause remains unclear, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic, environmental, and immune-related factors. The following are the main etiologies associated with acne rosacea:

1. Vascular Dysregulation-Abnormalities in the cutaneous blood vessels can lead to flushing, persistent redness, and the development of telangiectasia (visible blood vessels). Triggers such as heat, alcohol, spicy foods, and emotional stress exacerbate vasodilation.

2. Immune Dysfunction-Overactivity of the innate immune system, particularly elevated levels of antimicrobial peptides like cathelicidins, leads to chronic inflammation and skin barrier dysfunction. Dysregulation of inflammatory pathways can contribute to skin hypersensitivity.

3. Microbial Factors-Demodex folliculorum, a microscopic mite commonly found on the skin, is present in higher densities in rosacea patients. Its interaction with the immune system may induce inflammation. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection has been suggested, as this bacterium produces vasoactive substances that might exacerbate rosacea symptoms.

4. Genetic Predisposition-A family history of rosacea increases the likelihood of developing the condition, though specific genetic mutations have not been clearly identified.

5. Ultraviolet Radiation-Prolonged UV exposure damages the dermal matrix and worsens inflammation, contributing to persistent erythema and telangiectasia.

6. Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers-Extreme temperatures, wind, humidity, and exposure to irritants like skincare products or cosmetics can worsen symptoms. Consumption of alcohol, caffeine, or spicy foods and emotional stress may exacerbate the condition.

7. Neurovascular Dysregulation-Dysregulation of nerve function in the skin can amplify flushing, burning, and stinging sensations seen in rosacea patients. Understanding these etiological factors is crucial for tailoring effective treatment strategies and advising patients on lifestyle modifications to minimize triggers.

Clinical Presentation

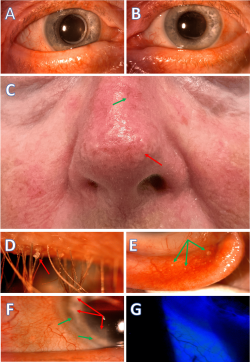

Facial features of rosacea include erythematous changes involving the malar region, nose, and eyelids. These characteristic changes range from mild discoloration to severe, violaceous changes to skin tone. Telangiectasias are another defining feature in this region. Some clinical presentations may include papulopustular changes.

Slit-lamp examination of the eyelid margins reveals telangiectasia and erythema of the lid margin in 50–94% of patients. Meibomian gland dysfunction is present in up to 92% of rosacea patients and is characterized by excess, abnormally turbid meibomian gland secretion, which causes plugging of the gland orifices and recurrent hordeolum/chalazion. Additionally, the ocular surface inflammation leads to interpalpebral bulbar conjunctival hyperemia, as well as follicular and papillary reaction.

Rhinophyma of the nose can occur as a late finding. Corneal alterations are also detected in 25–50% of patients with ocular rosacea and may range from mild punctate epithelial keratitis accompanying the blepharoconjunctivitis to corneal neovascularization, infiltration, ulceration and perforation.[3]

One potential severe complication on the spectrum of rosacea, Morbihan syndrome can present as insidious swelling of the forehead, nose, glabella, cheeks and periorbital regions of the face.[6] Common additional signs, similar to rosacea include erythema, telangiectasias, papules, pustules and facial flushing.[6]

Diagnosis

Originally, rosacea was classified by subtype by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee[7]:

- Erythematotelangiectatic

- Papulopustular

- Phymatous

- Ocular

Recently, the Global Rosacea Consensus Panel proposed both major and minor features that would classify rosacea. Diagnostic features are a persistent centrofacial erythema associated with periodic intensification by potential trigger factors and phymatous changes. Major features: flushing/transient centrofacial erythema, inflammatory papules and pustules, telangiectasia, and ocular manifestations (lid margin telangiectasia, blepharitis, and keratitis/conjunctivitis/sclerokeratitis). Minor features: burning sensation of the skin, stinging sensation of the skin, edema, and dry sensation of the skin.[2] Ocular manifestations may appear in the absence of other diagnostic phenotypes.[7]

Differential diagnosis

- Lupus erythematosus

- Herpes simplex keratitis

- Seborrheic or contact dermatitis

- Cellulitis

- Morbihan Syndrome (often associated with Rosacea)

- Atopic dermatitis

- Blepharoconjunctivitis associated with other causes

Management

Conservative management includes lifestyle modification (avoidance of triggers), warm compresses, eyelid scrubs, and digital massage.[2][4][8] Medical management varies depending on severity. To relieve the dry eye associated with ocular rosacea, artificial tears and lubricating agents are used.[2] Systemic, subantimicrobial tetracyclines (doxycycline, minocycline) and macrolides (azithromycin) are thought to decrease inflammation associated with rosacea and are often first-line agents for patients with moderate disease.[2][9][10] While antibiotics may present a great treatment option for patients with ocular rosacea, side effects should be considered (vaginal/oral candidiasis, gastrointestinal distress, photosensitivity, teratogenicity, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and allergies). At the lower doses used for ocular rosacea management, it is postulated that oral antibiotics have a favorable impact on matrix metalloproteinases, interleukins, nitric oxide, activated B-lymphocytes, and collagen abnormalities that have been associated with this disease.[2] Topical metronidazole has a grade A evidence rating for the treatment of mild to moderate inflammatory rosacea, with a small study showing an improvement in rosacea-related eyelid health.[2][4]

Immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclosporine, have also been used to reduce chronic eyelid and corneal inflammation.[2][4] Although the medical literature reports mixed results, interventional office treatments include Lipiflow/Intense Pulse Light therapy, meibomian gland expression, and punctal occlusion may be considered.[2][11][12] Intense Pulsed Light therapy in particular was demonstrated to increase the outflow of the meibomian glands thereby reducing bacterial counts seen in meibum stasis. It also causes the downregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators and stimulate alteration in the microcirculation thereby decreasing periocular inflammation and erythema.[13] Treatment of chalazia may require excision. Severe ophthalmic disease may require ocular surface reconstruction (amniotic membrane placement, conjunctival flap, tissue adhesives), and penetrating keratoplasty for corneal perforation.[2]

Future interventions may include novel therapies for various cytokines, chemokines, and angiogenesis factors. Chemodenervation (i.e. Botox) has recently been trialed for rosacea management, hypothesized to inhibit vasodilatory mechanisms.[14] As our knowledge of the cellular and molecular basis for ocular rosacea grows, the management will most likely transition to a highly-selective and more targeted approach.

Additional Resources

- Boyd K, Jimenez EM. Ocular Rosacea. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/ocular-rosacea-list. Accessed March 20, 2019.

References

- ↑ Khadamy J (January 01, 2024) Ocular Rosacea: Don’t Forget Eyelids and Skin in the Assessment of This Stubborn Ocular Surface Disease. Cureus 16(1): e51439. doi:10.7759/cureus.51439

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Wladis EJ, Adam AP. Treatment of Ocular Rosacea. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018 May - Jun;63(3):340-346. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2017.07.005. Epub 2017 Aug 4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Awais M, Anwar MI, Iftikhar R, Iqbal Z, Shehzad N, Akbar B. Rosacea - the ophthalmic perspective. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2015;34(2):161-6. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2014.930749. Epub 2014 Jul 9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Oge' LK1, Muncie HL2, Phillips-Savoy AR1. Rosacea: Diagnosis and Treatment.Am Fam Physician. 2015 Aug 1;92(3):187-96.

- ↑ Gurnani B, Christy J, Narayana S, Kaur K, Moutappa F. Corneal Perforation Secondary to Rosacea Keratitis Managed with Excellent Visual Outcome. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2022;14(27):162-167. doi:10.3126/nepjoph.v14i1.36454

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Helm KF, et al. A clinical and histopathologic study of granulomatous rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;25:1038.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;78(1):148–155.

- ↑ Layton AM. Pharmacologic treatments for rosacea. Clin Dermatol. 2017 Mar - Apr;35(2):207-212. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.10.016. Epub 2016 Oct 27.

- ↑ Wladis EJ, Bradley EA, Bilyk JR, Yen MT, Mawn LA. Oral Antibiotics for Meibomian Gland-Related Ocular Surface Disease: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2016 Mar;123(3):492-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.062. Epub 2015 Dec 23. PMID: 26707417.

- ↑ Webster GF, Durrani K, Suchecki J. Ocular rosacea, psoriasis, and lichen planus. Clin Dermatol. 2016 Mar-Apr;34(2):146-50. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2015.11.014. Epub 2015 Nov 22.

- ↑ Wladis EJ, Aakalu VK, Foster JA, Freitag SK, Sobel RK, Tao JP, Yen MT. Intense Pulsed Light for Meibomian Gland Disease: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2020 Sep;127(9):1227-1233. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.03.009. Epub 2020 Apr 21. PMID: 32327256.

- ↑ Dell SJ, Gaster RN, Barbarino SC, Cunningham DN. Prospective evaluation of intense pulsed light and meibomian gland expression efficacy on relieving signs and symptoms of dry eye disease due to meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:817–827. Published 2017 May 2. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S130706

- ↑ Bunya V, March de Ribot F, Barmettler A, Yen MT, Nguyen Barkat C. American Academy of Opthalmology Eye Wiki. Intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy. 2023.

- ↑ Scala J, Vojvodic A, Vojvodic P, Vlaskovic-Jovicevic T, Peric-Hajzler Z, Matovic D, Dimitrijevic S, Vojvodic J, Sijan G, Stepic N, Wollina U, Tirant M, Thuong NV, Fioranelli M, Lotti T. Botulin Toxin Use in Rosacea and Facial Flushing Treatment. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019 Aug 30;7(18):2985-2987. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.784. PMID: 31850105; PMCID: PMC6910814.

- Stone DU, Chodosh J. Ocular rosacea: an update on pathogenesis and therapy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15(6):499-502

- AAO Basic and Clinical Science Course, External Disease and Cornea, 2010-2011, 69-70.

- Papier A1, Tuttle DJ, Mahar TJ.Differential Diagnosis of the Swollen Red Eyelid. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Dec 15;76(12):1815-24.

- Celiker H, Toker E, Ergun T, Cinel L. An unusual presentation of ocular rosacea. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2017 Nov-Dec;80(6):396-398. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20170097.