Duane Retraction Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Duane Retraction Syndrome is a congenital strabismus syndrome occurring in isolated or syndromic forms. It presents with a variety of clinical features including diplopia, anisometropia, and amblyopia.

Disease Entity

H50.81 Duane's syndrome[1]

Disease

Duane retraction syndrome (also known as Stilling-Turk-Duane syndrome) is a congenital, nonprogressive strabismus syndrome most famously described by Alexander Duane in 1905.[2][3] Its characteristics include:

- Complete or partial (less common) absence of abduction[2]

- Widening of palpebral aperture with abduction[2]

- Retraction of globe on adduction[2]

- Narrowing of palpebral fissure during adduction (induced ptosis)[2]

- Partial deficiency of adduction[4]

- Oblique movement with attempts at adduction[4]

- Upshoot or downshoot of globe with adduction (Leash Phenomenon)[2]

- Deficiency of convergence[4]

Etiology

Duane retraction syndrome is present in about 1 out of every 1000 persons in the general population, with females making up 60% of affected individuals who have unilateral involvement.[3][5][6] Bilateral manifestations constitute an estimated 15 – 20 % of all reported cases of Duane retraction syndrome.[7][8] Accounting for up to 4% of all strabismus cases, it is the most common type of congenital aberrant ocular innervation.[5]

There are three major types of Duane retraction syndrome:

- Type 1 (75–80% of patients) presents with abduction more limited than adduction and a variably present an esotropia in primary gaze, with a compensatory head turn to the involved side

- Type 2 (5–10% of patients) presents with adduction more limited than abduction and a variably present with an exotropia in primary gaze with a compensatory head turn to the uninvolved side

- Type 3 (10-20% of patients) presents with abduction and adduction similarly limited, with either an esotropia or exotropia in primary gaze and a compensatory head turn to the involved side[9]

Most instances of Duane retraction syndrome are isolated with no known association with other diseases. Isolated forms most often occur sporadically and typically are unilateral, with a left eye predominance.[5][6] Genetic and hereditary factors play a significant role in the etiologic spectrum. Ten percent of isolated instances are inherited, and these usually present bilaterally with associated vertical movement abnormalities.[5] The inherited isolated forms can be associated with either dominant or recessive autosomal mutations:

- Type 1: autosomal dominant (locus 8q13)[3]

- Type 2: autosomal dominant (mutation of CHN1 at DURS2 locus 2q31-q32.1)[3][10]and autosomal recessive.[10] Alterations in the DURS2 gene likely interfere with the ontogenesis of abducens motor neurons and exert a milder effect on oculomotor nerve development.[11]

Syndromic and systemic associations are also well- recognized. About 30% of the time, Duane retraction syndrome is associated with other congenital anomalies (syndromic forms).[5][6] Commonly associated diseases and characteristic features include Okihiro syndrome (radial ray), Wildervanck syndrome (Klippel-Feil anomaly, deafness), Moebius syndrome (congenital paresis of facial and abducens cranial nerves), Holt–Oram syndrome (abnormalities of the upper limbs and heart), Morning Glory syndrome (abnormalities of the optic disc), and Goldenhar syndrome (malformation of the jaw, cheek and ear, usually on one side of the face).[5][6][9] Syndromic forms of Duane restriction syndrome can result from various mutations, depending on the associated syndrome. For example, Okihiro syndrome–related forms are autosomal dominant (SALL4 mutations), Goldenhar syndrome–related instances are mostly sporadic with both autosomal dominant and recessive forms, and Wildervanck syndrome–related instances are irregularly dominant with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity.[2][9]

General Pathology

Duane retraction syndrome is attributed to agenesis or dysplasia of the abducens motor neurons, with aberrant innervation of the lateral rectus muscle by a misdirected branch of the oculomotor nerve.[9] As observed in other congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders, the absent or deficient input from the primary motor nucleus is partially compensated by neighboring cranial pathways. In Duane retraction syndrome, this maladaptive substitution leads to paradoxical co-innervation of the lateral rectus muscle by the oculomotor nerve, while its normal abducens nerve innervation remains incomplete or absent. One proposed theory is that the spatial proximity of the oculomotor and abducens nerves within the cavernous sinus and orbital apex facilitates axonal misrouting during embryogenesis, thereby underpinning the anomalous neural cross-connections that underlie this syndrome.[12] The outcome is a distinctive dysinnervational pattern characterized by simultaneous activation of the medial and lateral rectus muscles during attempted adduction, producing the hallmark presentation of globe retraction and limitation of abduction.

Pathophysiology

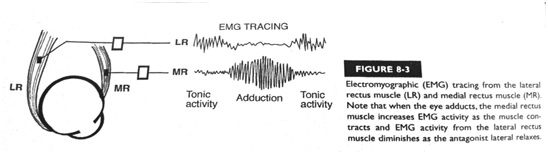

Historically, two principal theories have been described to explain the pathogenesis of Duane retraction syndrome: the myogenic and neurogenic theories. The myogenic theory, suggested by early studies, describes fibrosis or inelasticity of the lateral rectus muscles and abnormally posterior insertion of the medial rectus muscle.[9] Although this theory accounted for some of the mechanical features observed, it did not explain the characteristic paradoxical movements and co-contraction patterns. In addition, some of these structural anomalies may likely arise secondary to aberrant innervation, reflecting the complex interplay between neurogenic input and muscle development. On the contrary, the neurogenic theory, now widely commonly accepted, originated in postmortem studies conducted by researchers at the John Hopkins University in the 1980s.[13] This theory proposes that a disturbance in embryologic development between weeks 4–8 results in an absent abducens nerve with anomalous innervations of the lateral rectus muscle by a branch of the oculomotor nerve, coinciding with the differentiation and migration of abducens motor neurons.[13] Simultaneous activation of the medial and lateral rectus muscles may be the cause of global retraction (Figure 1).[14]

High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has since corroborated these original findings.[15] In many patients with Duane retraction syndrome, the abducens nerve is absent or markedly hypoplastic, and in some, the oculomotor and optic nerves are also underdeveloped.[16] Electromyographic studies have provided compelling physiologic evidence for this mechanism. Absent lateral rectus electrical activity during abduction and paradoxical activation during adduction was first documented in 1956.[17] Subsequent investigations confirmed that the degree of aberrant co-innervation varies widely, comprising patterns of synergistic activation not only with the medial rectus but also with superior and inferior rectus muscles.[18] These observations substantiate the concept that Duane retraction syndrome represents a continuum of dysinnervational phenotypes, rather than a single discrete entity.[19] With this disease paradigm, the variability in clinical presentation – ranging from esotropic to exotropic deviations and differing degrees of vertical overshoot – reflects the proportion and spatial distribution of normal versus aberrant innervation received by lateral rectus, as well as the specific horizontal gaze position at which anomalous innervation is activated.

Risk Factors

The only known risk factor for the isolated type of Duane retraction syndrome is a germline mutation in one of the associated genes, in which an affected parent has a 50% chance of transmitting the mutation to their child. Yet, this hereditary form accounts for only 10% of isolated cases, as the remaining 90% arise sporadically.[5] An affected parent is also a risk factor for the syndromic forms; however, the chance of passing an affected gene onto offspring varies according to the associated syndrome.

Primary Prevention

No means of primary prevention have been identified.

Diagnosis

Clinical Exam

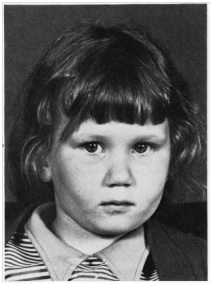

Evaluation of Duane retraction syndrome follows standard strabismus assessment principles – measurement of visual acuity, ocular motility, binocular status, and refraction. Frank strabismus in the primary gaze is present in 76% of individuals with Duane retraction syndrome.[3] Other clinical features include compensatory head turn to avoid diplopia (Image 1),[20] limitation of abduction, induced ptosis on adduction (Image 2),[5] poor binocular vision, and anisometropia. Visual acuity is typically normal, although amblyopia occurs in about 10% of individuals and generally responds well to early conventional therapy.[3] Hyperopia remains the most common refractive error observed.[8]

Comprehensive evaluation of ocular ductions is essential to define the extent of abduction and adduction deficits, globe retraction, and anomalous vertical movements. Measuring the palpebral fissure width in adduction and abduction provides an indirect estimate of the degree of aberrant lateral rectus innervation. Forced duction, forced augmentation, and force generation tests help differentiate mechanical restriction or muscle contracture from innervation deficits, while the force generation test also confirms paradoxical lateral rectus co-contraction in Type II and Type III disease.[21]

Alphabetical patterns, most commonly a V-pattern, arise from co-activation of the horizontal and vertical recti rather than oblique muscle dysfunction.[22] Accurate prism-covering testing with controlled fixation is essential, as the secondary deviation (when the affected eye fixates) invariably exceeds the primary deviation. Because Duane retraction syndrome is often associated with other ocular systemic congenital anomalies, including sensorineural hearing loss and craniofacial abnormalities, individuals should undergo a thorough systemic examination to ensure accurate diagnosis and comprehensive management. Photographic documentation of ocular motility and anomalous head position is helpful for future review.[9]

Laboratory Tests

Molecular genetic testing of CHN1 is available, and is recommended only in familial cases.[9]

Imaging Techniques

As noted above, in Duane retraction syndrome, MRI may show absence or hypoplasia of the abducens nerve, and in some cases, the oculomotor and optic nerves. However, imaging is not typically recommended for diagnostic purposes. Brain and orbital MRI can be completed prior to surgical intervention for better visualization of orbital anatomy.[9]

Differential Diagnosis

While diagnosis of Duane retraction syndrome is generally based on its hallmark features – limited horizontal motility, globe retraction, and narrowing of the palpebral fissures on adduction - in subtle or atypical presentations, particularly in young children, it may be confused with congenital sixth nerve palsy, especially in esotropic cases with limited abduction and minimal retraction. Key distinguishing features include the absence of globe retraction and anomalous vertical movements in sixth nerve palsy, which also has a larger esotropic angle. Similarly, exotropic Duane retraction syndrome may resemble oculomotor nerve palsy, though the latter lacks both globe retraction and vertical overshoots.

Furthermore, the differential diagnosis of Duane retraction syndrome encompasses a wide range of congenital and restrictive motility disorders that manifest as strabismus or limitations of extraocular movements. This includes, but is not limited to, Okihiro syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Wildervanck syndrome, Moebius syndrome, Holt–Oram syndrome, Morning Glory syndrome, abducens nerve palsy, Brown syndrome, Marcus–Gunn jaw winking syndrome, and infantile esotropia. Traumatic restrictive strabismus and accessory or anomalous extraocular muscles can also mimic Duane retraction syndrome, particularly when they produce globe retraction and variable motility limitation. In these cases, orbital imaging, such as high-resolution MRI, can often be invaluable for distinguishing Duane retraction syndrome from other structural and syndromic disorders.

As previously described, Duane retraction syndrome is frequently accompanied by additional congenital anomalies, a fact of considerable diagnostic importance when evaluating patient with atypical strabismus. Approximately one-third of the patients exhibit systemic malformations, with musculoskeletal, auditory, and limb defects occurring far more often than in the general population.[23] Associated ocular abnormalities include iris dysplasia, pupillary defects, cataract, heterochromia, coloboma, nystagmus, ptosis, epibulbar dermoids, and optic nerve hypoplasia. Systemic findings commonly affect the craniofacial region, spine, and extremities, including preauricular tags, spina bifida, Chiari I malformation, cleft palate, rib and foot anomalies, and sensorineural hearing loss. Syndromic associations include Goldenhar, Klippel-Feil, and Duane-plus variants.

Management

Evaluation Following Diagnosis

Evaluation should include a family history, assessment of family members who may be at risk in the first year of life, and consideration of genetic counseling if a familial pattern is identified.

Non-Surgical Management

Spectacles or contact lenses can be prescribed to address refractive error, with prism glasses used in select situations to improve compensatory head position.[9] A small study (4 patients) conducted in 2008 found that extraocular muscle injections of botulinum toxin may help to decrease the amount of deviation and lessen the upshoot or downshoot of the globe with adduction ("leash phenomenon").[24] Amblyopia can be managed with standard therapy. [9]

Surgical Management

Patients should be counseled that no current medical or surgical intervention can fully restore normal ocular motility across all gaze positions, as the primary defect of nerve innervation persists. Surgery, therefore, does not cure Duane retraction syndrome; instead, it aims to correct the deviation in the primary position, thereby improving a compensatory head position that can occur in some individuals.[9] [25] It can also improve the leash phenomenon.[9]

Indications for Surgery

A patient should be considered for surgical correction if they have at least one of the following characteristics:

- an abnormal head position greater than or equal to 15 degrees[25]

- a significant deviation in the primary position[25]

- severe induced ptosis: a reduction of greater than or equal to 50% of the width of the palpebral fissure on adduction[26]

Pre-Surgical Evaluation

Key clinical variables guiding surgical planning include the residual abduction and adduction function (reflecting lateral rectus innervation), the degree of globe retraction, the presence of anomalous vertical rectus innervation that produces upshoot or downshoot, the primary-position deviation, and abnormal head posture. In addition, any atypical vertical or torsional ocular movements, such as outward rotation in upgaze or downgaze from lateral rectus overaction, as well as evidence of muscle contracture on forced-duction testing, should be considered.[9]

The sporadic occurrences of accessory fibrous bands in Duane restriction syndrome may contribute to mechanical impediments and should be anticipated during surgical planning.[27] Brain and orbital MRI should be considered before surgery for better visualization of orbital anatomy.

Principles of Surgical Approach

The surgical approach in Duane retraction syndrome is highly individualized, with no universally accepted standard of care. The specific approach will depend on factors such as the primary deviation, severity of co-contraction and globe retraction, presence of anomalous vertical movements, and forced duction and force generation findings. Described below are details of each surgical option for Duane retraction syndrome based on the specific presentations:

Duane retraction syndrome with esotropia

Unilateral medial rectus recession is a commonly employed method for surgical correction in Type 1 Duane retraction syndrome with esotropia, particularly when a moderate compensatory head turn is present.[28] By weakening the medial rectus and thereby reducing its tonic adducting force, the eye can be realigned toward primary position, hence improving or eliminating face turn and frequently preserving good stereoacuity. However, medial rectus recession does not improve abduction and may have a limited duration of effect.[29] Typically, the medial rectus is recessed 4-5 mm posterior to its original insertion. While some have reported an larger recessions, caution is warranted since moving the insertion beyond about 5 mm risks significant adduction limitation that can produce new diplopia, consecutive exotropia, or synergistic divergence due to unopposed anomalous contraction of the lateral rectus, particularly in patients with pre-operative limitations in adduction.[28] Adjustable sutures may be used to allow postoperative fine-tuning when alignment is uncertain. Addition of a contralateral medial rectus recession is occasionally warranted to manage large-angle esotropia.[30]

Vertical rectus transposition can be considered when severe abduction limitation or a restricted field of single binocular vision is present. In this procedure, the superior and/or inferior rectus muscles are detached and transposed laterally to lie adjacent to the lateral rectus insertion.[20][31] By redirecting an existing vertical force laterally, a new abducting vector can be created effectively. Several vertical rectus transposition techniques have been reported, including Nishida transposition, full (i.e. superior and inferior rectus) transposition, and superior rectus transposition. Vertical rectus transposition can improve abduction and binocular vision more effectively than medial rectus recession alone, and is often preferred unless the primary deviation is small with relatively preserved abduction.[29] However, medial rectus recession or pharmacological weakening with botulinum toxin should be considered if forced duction testing reveals a restricted or fibrotic medial rectus muscle. Augmentation sutures (Foster technique) can increase the abducting effect but may be most beneficial when the primary deviation or head turn exceeds 20 prism diopters.[29] [32]

Superior rectus transposition — with or without medial rectus recession — has emerged as an effective alternative to full vertical rectus transposition. Superior rectus transposition provides similar improvements in abduction and primary-position esotropia while requiring the disinsertion of fewer muscles, reducing both operative time and the theoretical risk of anterior segment ischemia. This approach is particularly useful in situations where medial rectus recession must be minimized to preserve adduction.[29]

Duane retraction syndrome with exotropia

For Duane restriction syndrome with exotropia, where anomalous lateral rectus innervation predominates, unilateral lateral rectus recession of as much as 7-10mm is often the preferred procedure.[33][34] When the deviation exceeds 25 PD, contralateral lateral rectus recession may be considered, which is usually performed asymmetrically, with the fellow eye recessed slightly more.[35] If there is marked globe retraction or clear evidence of anomalous lateral rectus innervation, weakening the contralateral lateral rectus is generally avoided; otherwise, the increased innervational demand on the affected lateral rectus can paradoxically aggravate exotropia. In cases with severe paradoxical lateral rectus tightness, lateral rectus weakening techniques such as periosteal fixation or lateral rectus extirpation, occasionally followed by transposition procedures to restore abducting force, can be utilized.[29] These transposition techniques are primarily described in the context of abduction disorders but may be applied selectively in exotropic Duane retraction syndrome, particularly when severe globe retraction persists despite maximal lateral rectus recession.

Severe Globe Retraction and Co-Contraction

When globe retraction is prominent, concurrent recession of both horizontal recti in the affected eye can be an effective strategy. Large recessions are typically performed, with the lateral rectus recessed approximately 1 mm more than the medial rectus to preserve balance in primary gaze. The relative amount of weakening is adjusted depending on the primary-position deviation.[36] This approach reduces the powerful co-contraction forces that cause narrowing of the palpebral fissure during adduction. It is important to note that recession of horizontal recti alone does not typically improve abduction, but may be justified when the predominant goal is relief of retraction, improvement of cosmesis, or reduction of head turn.[29]

Vertical Overshoots and Mechanical Upshoot/Downshoot

The Y-splitting of the lateral rectus is an effective technique for addressing the pronounced upshoots and downshoots that arise from the mechanical leash phenomena in Duane retraction syndrome. In this procedure, the lateral rectus muscle is divided longitudinally from its insertion posteriorly toward the globe’s equator, thereby creating superior and inferior halves. These halves are spread approximately 20 mm apart and each reattached individually to the sclera, typically with a small concomitant recession that is adjusted according to the degree of primary-position deviation and a greater recession when esotropia is present.[37] This anatomical redistribution of the muscle’s vertical force vectors effectively dampens the abrupt vertical overshoots characteristic of co-contraction and reduces the magnitude of globe retraction by minimizing the vertical displacement of the muscle during adduction,

Faden procedures, or posterior fixation sutures, may also be utilized to prevent lateral rectus side-slipping and thereby control severe upshoots or downshoots. In this surgical approach, the targeted muscle is sutured to the sclera several millimeters behind its insertion to create a posterior anchor that controls excessive excursion without altering primary-position alignment.

Chronic innervational upshoots in Duane retraction syndrome may lead to secondary contracture of a vertical rectus muscle, most frequently the superior rectus, resulting in a persistent hypertropia.[38] Surgical management involves a substantial recession of the contracted muscle to reduce its pathological vertical pull and restore ocular alignment. In addition to correcting the vertical deviation, the recession can alleviate globe retraction by releasing the chronic upward tethering effect imposed by the contracted muscle.

Careful distinction between mechanical overshoots and innervational vertical misalignment is essential, as the former responds well to Y-splitting, whereas the latter may require vertical muscle surgery or be worsened by transposition procedures if unrecognized.[29]

Complications of Surgery

See Strabismus Surgery Complications. More specific to surgery for Duane retraction syndrome, complications can include under-correction of primary position esotropia and the compensatory head turn or over-correction leading to secondary exotropia. New vertical deviations can also occur after vertical rectus transposition procedures.[26] Transposition procedures involving multiple rectus muscles carry the risk of anterior segment ischemia, because each rectus muscle contributes anterior ciliary vessels to the anterior segment. The risk increases when three or more rectus muscles are operated on within a short period, or when patients have vascular comorbidities. Partial vertical rectus transposition, Jensen procedures, and muscle-sparing transpositions are strategies designed to preserve ciliary circulation when anterior segment ischemia risk is a concern.[29]

Surveillance

After diagnosis, ophthalmologic exams are required every 3–6 months to evaluate for amblyopia. Patients aged 7–12 years who are no longer at risk for amblyopia and have good binocular vision can be evaluated annually or biannually.[9]

Additional Resources

For more information on Duane retraction syndrome and for a video of the surgery to correct associated strabismus, visit the Children’s Hospital Boston’s webcast.[39]

References

- ↑ ICD10data.com. 2026 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code H50.81 Duane's syndrome. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/H00-H59/H49-H52/H50-/H50.81. [Accessed 12/26/2025].

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Kirkham, T.H. Inheritance of Duane's syndrome. Brit. J. Ophthal. 1970; 54 : 323-329.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 University of Arizona Department of Ophthalmology and Vision Science. Duane Retraction Syndrome 1. Hereditary Ocular Disease. http://disorders.eyes.arizona.edu/disorders/duane-retraction-syndrome-1. [July 14, 2012].

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Elliot, A.J. Duane's Retraction Syndrome. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1945; XXXVIII: 463-465.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Murillo-Correa CE et al. Clinical features associated with an I126M α2-chimaerin mutation in a family with autosomal dominant Duane retraction syndrome. JAAPOS. 2009;13(3):245-248.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 National Human Genome Research Institute. Learning About Duane Syndrome. Genome.gov. http://www.genome.gov/11508984. [September 24, 2013].

- ↑ Khan AO, Oystreck D. Clinical characteristics of bilateral Duane syndrome. J aapos. Jun 2006;10(3):198-201. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.02.001

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 DeRespinis PA, Caputo AR, Wagner RS, Guo S. Duane's retraction syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. Nov-Dec 1993;38(3):257-88. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(93)90077-k

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 Andrews CV et al. Duane Syndrome. GeneReviews. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1190/. [July 14, 2012].

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Miyake N et.al. CHN1 Mutations are not a Common Cause of Sporadic Duane’s Retraction Syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152:215-217.

- ↑ Miyake N, Chilton J, Psatha M, et al. Human CHN1 mutations hyperactivate alpha2-chimaerin and cause Duane's retraction syndrome. Science. Aug 8 2008;321(5890):839-43. doi:10.1126/science.1156121

- ↑ Hoyt WF, Nachtigäller H. Anomalies of ocular motor nerves. Neuroanatomic correlates of paradoxical innervation in Duane's syndrome and related congenital ocular motor disorders. Am J Ophthalmol. Sep 1965;60(3):443-8.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hotchkiss MG et al. Bilateral Duane's Retraction Syndrome A Clinical-Pathologic Case Report. Arch Ophthalmol.1980;98:870-874.

- ↑ Duane TD. Clinical Ophthalmology. Pediatric Ophthalmic Surgery. Vol. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1994.

- ↑ Parsa CF, Grant PE, Dillon WP, Jr., du Lac S, Hoyt WF. Absence of the abducens nerve in Duane syndrome verified by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Ophthalmol. Mar 1998;125(3):399-401. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80158-5

- ↑ Matteucci P. I difetti congeniti di abduzione con particolare riguardo alla patogenesi. Rassegna Ital Ottalmologia. 1946;15:345-380.

- ↑ Breinin G. In discussion of: De Gindersen T, Zeavin B. Observations on the retraction syndrome of Duane. Arch Ophthalmol. 1956;55:576.

- ↑ Huber A. Electrophysiology of the retraction syndromes. Br J Ophthalmol. Mar 1974;58(3):293-300. doi:10.1136/bjo.58.3.293

- ↑ Assaf AA. Congenital innervation dysgenesis syndrome (CID)/congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders (CCDDs). Eye (Lond). Oct 2011;25(10):1251-61. doi:10.1038/eye.2011.38

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gobin MH. Surgical Management of Duane’s Syndrome. Brit. J. Ophthal.1974;58(301):301-306.

- ↑ Romero-Apis DE. Aspectos clínicos y tratamiento. Mexico, DF DALA. 2010:141-56.

- ↑ Scott AB, Wong GY. Duane's syndrome. An electromyographic study. Arch Ophthalmol. Feb 1972;87(2):140-7. doi:10.1001/archopht.1972.01000020142005

- ↑ Pfaffenbach DD, Cross HE, Kearns TP. Congenital anomalies in Duane's retraction syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. Dec 1972;88(6):635-9. doi:10.1001/archopht.1972.01000030637013

- ↑ Talebnejad M et al. Management of Duane’s Syndrome with Botulinum Toxin Injection. Iranian J of Ophthal. 2008;20(3):10-14.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Barbe ME et al. A simplified approach to the treatment of Duane’s syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:131-138.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Duane TD. Clinical Ophthalmology. Strabismus, Refraction, The Lens. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1993.

- ↑ Pineles SL, Velez FG. Accessory fibrotic lateral rectus muscles in exotropic Duane syndrome with severe retraction and upshoot. J aapos. Dec 2015;19(6):549-50.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2015.05.023

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Natan K, Traboulsi EI. Unilateral rectus muscle recession in the treatment of Duane syndrome. J AAPOS. Apr 2012;16(2):145-9. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.11.012

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 Doyle JJ, Hunter DG. Transposition procedures in Duane retraction syndrome. J AAPOS. Feb 2019;23(1):5-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2018.10.008

- ↑ Kaban TJ, Smith K, Day C, Orton R, Kraft S, Cadera W. Single medial rectus recession in unilateral Duane syndrome type I. American Orthoptic Journal. 1995;45(1):108-114

- ↑ Yazdian Z, Rajabi MT, Ali Yazdian M, Rajabi MB, Akbari MR. Vertical rectus muscle transposition for correcting abduction deficiency in Duane's syndrome type 1 and sixth nerve palsy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. Mar-Apr 2010;47(2):96-100. doi:10.3928/01913913-20100308-07

- ↑ Velez FG, Foster RS, Rosenbaum AL. Vertical rectus muscle augmented transposition in Duane syndrome. J aapos. Apr 2001;5(2):105-13. doi:10.1067/mpa.2001.112677

- ↑ Sukhija J, Singh M, Singh U. Profound weakening of the lateral rectus muscle with attachment to lateral canthal tendon for treatment of exotropic Duane syndrome. J aapos. Jun 2012;16(3):298-300. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.01.013

- ↑ Sharma P, Tomer R, Menon V, Saxena R, Sharma A. Evaluation of periosteal fixation of lateral rectus and partial VRT for cases of exotropic Duane retraction syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol. Feb 2014;62(2):204-8. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.121145

- ↑ Kraft SP. A surgical approach for Duane syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. May-Jun 1988;25(3):119-30. doi:10.3928/0191-3913-19880501-06

- ↑ Sprunger DT. Recession of both horizontal rectus muscles in Duane syndrome with globe retraction in primary position. J aapos. Mar 1997;1(1):31-3. doi:10.1016/s1091-8531(97)90020-3

- ↑ Jampolsky A. Discussion of Eisenbaum AM, Parks MM. A Study of Various Surgical Approaches to the Leash Effect in Duane’s Syndrome, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus and the American Academy of Ophthalmology, Chicago. 1980;

- ↑ Arora P, Ganesh S, Shanker V. Duane′ s retraction syndrome with severe upshoot and ipsilateral superior rectus contracture: a rare presentation. Journal of Clinical Ophthalmology and Research. 2014;2(2):108-110.

- ↑ Children’s Hospital Boston. Aligning the Eyes. OR Live. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x95WpZtvio0. [September 24, 2013].