Amblyopia

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Amblyopia is a relatively common disorder and a major cause of visual impairment in children. It represents an insult to the visual system during the critical period of development whereby an ocular pathology (ex. strabismus, anisometropia, high refractive error, or deprivation) interferes with normal cortical visual development. Approximately 3-5% of children are affected by amblyopia.[2]

Definition

Amblyopia represents diminished vision occurring during the years of visual development secondary to abnormal visual stimulation or abnormal binocular interaction. It is usually unilateral but it can be bilateral. The diminished vision is beyond the level expected from the ocular pathology present.

Etiology

Bilateral amblyopia is less common than unilateral amblyopia. Bilateral cases are caused by bilateral image blur (anterior visual pathway). Examples of etiologies for bilateral amblyopia include bilateral media opacities (including corneal opacities, infantile or childhood cataracts, or vitreous hemorrhages), or ametropia (bilateral high astigmatism or high hypermetropia). Unilateral causes of amblyopia also include the same types of media opacities seen in bilateral cases. However, the most common causes of unilateral amblyopia are strabismus and anisometropia, or a combination of the two[3][4]

The etiologies of amblyopia can be easily remembered with the following mnemonic: S.O.S. Spectacles (anisometropia or high myopic or hyperopic refractive error), Occlusion (media opacities, retinal disease, optic nerve pathology, corneal disease, etc.), and Strabismus.

Risk Factors

A positive family history of strabismus, amblyopia, or media opacities would increase the risk of amblyopia in the child. Children who have conditions that increase the risk of strabismus, anisometropia, or media opacities (including Down syndrome) would also be at increased risk for the development of amblyopia. The risk of developing amblyopia, from a condition that is known to cause amblyopia, diminishes as the child approaches 8-10 years of age. As a corollary to this, the depth of amblyopia is typically less severe the older the child is at the time of onset of the amblyogenic factor.

General Pathology

In cases of bilateral amblyopia, the basic pathology is a significant blurred retinal image in each eye causing a disruption of normal visual development. This disruption must occur during the critical period of visual development (the first 8-10 years of life). The depth of damage depends on the severity of the blur, the length of time of the abnormal vision, and the age of onset of the insult. The pathology involved in unilateral amblyopia can be twofold. Retinal image blur in one eye can inhibit cortical activity from one eye, preventing normal visual development. Alternatively, misaligned eyes can prevent the normal process of fusion from taking place. This can result in suppression of the deviating eye, diminishing the acuity of the eye, and loss of binocularity. Sensory amblyopia is more severe than strabismic or anisometropic amblyopia and is tough to treat. Among strabismic amblyopias, esotropia is more prone to develop amblyopia as the fovea of the deviating eye has to compete with the stronger nasal retina (temporal hemifield) of the fellow eye which results in suppression of the deviating eye.

Pathophysiology

Abnormal visual stimulation during the critical period of visual development results in brain damage. Structural and functional damage occurs in the lateral geniculate nucleus and the striate cortex of the visual center in the occipital lobe in the form of atrophy of connections, loss of cross-linking between connections, and loss of laterality of connections.

Primary Prevention

The key to prevention is detection. There are numerous techniques to detect amblyopia, all with varying degrees of specificity, sensitivity, complexity, and cost. These include a complete ophthalmic examination, photoscreening, visual evoked potentials, acuity charts, and tests of stereopsis and binocular function. Children who are at higher risk for amblyopia should be watched closely for early signs of this condition. In general, the quicker amblyopia is detected and addressed, the less negative effect it has on the visual system. Vision screening is advocated on the state level to screen as many children as possible for this disease prior to the age of kindergarten. Early intervention results in better overall vision. This is why the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology all support pre-kindergarten vision screening for children.

Diagnosis

Amblyopia should be considered as a possible diagnosis in children with asymmetric visual behavior or acuity. It can also complicate the course of children with strabismus, or unilateral ocular or adnexal pathology such as a cataract, eyelid capillary hemangioma, or corneal scar. Bilateral amblyopia can also occur and should be thought of when a bilateral ocular condition occurs and despite treatment, some degree of diminished acuity persists. A careful history, thorough physical examination, and knowledge of possible etiologies of amblyopia can help the clinician to diagnose this condition.

History

Parents will often bring their child to the Ophthalmologist because of the underlying cause of the amblyopia (ptosis, strabismus, leukocoria, eyelid hemangioma), without realizing that amblyopia is present. In fact, anisometropic amblyopia usually goes undetected until picked up by a vision screening. The overwhelming majority of children with unilateral amblyopia do not complain of decreased acuity because they do not notice it unless one eye is occluded. The history taking process should include any family history of vision problems (specifically amblyopia and strabismus). Parents should be asked if the child was premature, and if they have ever noted any eye misalignment. Any prior testing (including school or Pediatrician vision screening, neuroimaging) should be noted. If any abnormality in the child's visual behavior has been noted, the duration is important. Also, some children may already have received care for amblyopia somewhere else. If this is the case, type of treatment and duration should be determined. Old records can be helpful.

Physical Examination

Examination should consist of the following:

- Acuity testing (age appropriate): Single optotypes (without crowding bar) are not recommended as a good acuity testing technique in amblyopes because this test will tend to underestimate the degree of amblyopia (crowding phenomenon).

- Record the power of any current spectacles

- Subjective refraction if age appropriate

- Tests of stereopsis and binocular function (including Worth 4 dot testing, TNO stereo test)

- External examination (looking for ptosis, lid hemangioma or other lesion which could affect visual development)

- Presence or absence of an afferent pupil defect[5]

- Anterior segment examination (looking for any media opacity, or irregularity)

- Motility and ocular alignment

- Funduscopic examination

- Cycloplegic retinoscopy

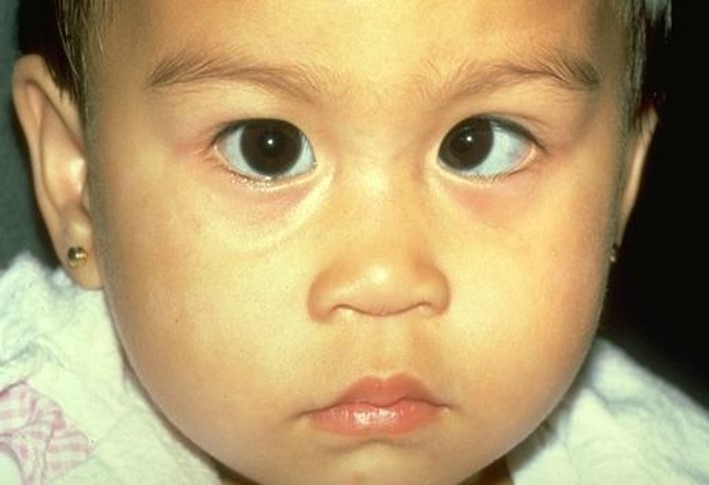

Signs

The presence or absence of signs of amblyopia would depend on what the underlying etiology for the amblyopia is. Deprivational amblyopia could manifest with ptosis, an eyelid hemangioma, or a cataract for example. Strabismic amblyopia may show a constant or intermittent ocular deviation. Esotropia causes more amblyopia as compared to exotropia since esotropia is constant and exotropia is usually intermittent in nature. Anisometropic amblyopia often shows no obvious signs when observing the patient, but cycloplegic retinoscopy will reveal the anisometropia. On clinical examination, unilateral amblyopia will show asymmetric visual behavior or acuity testing results (although not all patients with asymmetric acuity have amblyopia). Severe cases may have a mild afferent pupillary defect. The crowding phenomenon is important to be aware of when testing visual acuity in an amblyope. The amblyopic eye of these patients will visualize individual letters better than a whole line of letters. Therefore, if the visual acuity tester uses individual letters (without crowding bar), then they may underestimate the degree of amblyopia that is present or miss it entirely. A neutral density filter significantly reduces vision in organic disease, but generally does not in pure amblyopia.

Symptoms

Patients with unilateral amblyopia are often asymptomatic. Occasionally, patients will complain that one eye is blurry, or younger children may report discomfort in the affected eye. Torticollis occurs infrequently. Poor depth perception or clumsiness may be noted.

Clinical Diagnosis

In cases of unilateral amblyopia, the diagnosis requires two components. First, the patient must have a condition that can cause unilateral amblyopia. Examples would include strabismus, anisometropia, or a deprivational cause (ptosis, cataract, etc.). Second, the patient must have residual asymmetric acuity beyond the level expected from the underlying condition or that persists after treatment of the underlying condition. For example, a child with anisometropic hyperopia receives proper spectacle correction. Acuity in the more hyperopic eye improves but is still below that of the less hyperopic eye. This asymmetry of acuity represents amblyopia. In cases of bilateral amblyopia, a condition must be present during the critical years of visual development which produces constant, significant visual blur. Examples of such conditions would include bilateral vitreous hemorrhages, bilateral cataracts, bilateral corneal pathology, bilateral high hypermetropia, or bilateral high astigmatism.

Diagnostic Procedures

A normal, comprehensive ophthalmic examination is usually all that is necessary to diagnose amblyopia. Components of this examination include (but are not limited to): acuity testing, cycloplegic refraction and retinoscopy, tests of stereopsis and binocular vision, evaluation of pupillary responses, anterior segment examination, cover-uncover and alternate-cover testing, and dilated funduscopic examination. See the Physical Examination section above.

Laboratory test

Laboratory testing is not a typical feature of amblyopia diagnosis. Certainly if the etiology of the amblyopia was unclear, or if vision was deteriorating despite treatment, neuroimaging would be considered. Fundus dystrophies (specifically Stargardt disease) may have normal appearing fundus in early stages with unexplained vision loss. Such patients may need fundus photo, fluorescein angiogram, optical coherence tomography of macula, and electrophysiological tests. Patients with high astigmatism may need corneal topography to rule out keratoconus.

Differential diagnosis

There are cases of decreased acuity in children in which amblyopia is not present. Ocular pathology or refractive error (or even improper spectacle correction) may cause decreased acuity without any superimposed amblyopia. Prechiasmal lesions or optic nerve insult can also produce unilateral decreased acuity.

Management

Although there is much practitioner variability in the treatment of amblyopia, the general idea is to first treat the underlying cause for the amblyopia. Examples of this treatment would include prescribing glasses for anisometropia, strabismus surgery or spectacles to eliminate strabismus, or removal of a unilateral cataract to eliminate the media opacity. In unilateral or asymmetric cases of amblyopia, if there is a residual visual deficit after the underlying etiology is treated then amblyopia is said to exist. This can be addressed with occlusion therapy, pharmacologic therapy, or some other less commonly used modalities. Much of the data on the success of various treatment modalities for amblyopia through the years has come from retrospective, single site chart-review type studies. Over the last decade, there has been an explosion of amblyopia research. The need for prospective randomized trials in the treatment of amblyopia has begun to be met by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG). This is an NEI-funded network including both University-based and community-based clinicians. The power of such a group lies in its ability to conduct multiple trials in a cost-effective fashion, with simple protocols implemented as part of routine practice[6]. Patients are enrolled at multiple clinical sites in a prospective randomized fashion, with standardized visual testing protocols[7].Important data derived from these studies is present throughout this section on amblyopia.

General treatment

The key to optimal treatment of amblyopia is early detection and intervention. In symmetric bilateral cases, treatment consists of addressing the etiology of the diminished vision. Often there is residual bilateral amblyopia which may improve over time[8]. In asymmetric cases or unilateral cases, active treatment with patching, pharmacologic agents, or some less commonly used modalities can often improve the residual visual deficit.

Medical therapy

In anisometropic patients, some improvement in amblyopia can occur with glasses alone. Starting treatment in this manner may lessen the burden of subsequent amblyopia therapy for those with denser levels of amblyopia and in some cases may obviate the need for patching or pharmacologic penalization. Patching of the sound eye to improve the acuity of the amblyopic eye is the most commonly used technique to treat amblyopia. Patching compliance is a major concern, with high rates of poor compliance or noncompliance in some studies. Compliance with therapy can be bolstered by parental education and improving parental attitudes towards patching therapy. The number of prescribed patching hours per day varies widely between practitioners. In general most doctors recommend heavier patching regimens for worse degrees of amblyopia. The thought behind this is that heavier patching would improve results and the rapidity of obtaining them. However this practice has been called into question by recent PEDIG studies.

A study of severe amblyopes randomized the patching regimen to 6 hours of prescribed patching per day versus 12 hours per day. At the 4-month outcome visit, acuity improvements and rapidity of improvement were essentially identical between the groups[9]. A similar study of moderate amblyopes comparing 2 hours of prescribed patching per day to 6 hours per day, also found no difference in results[10]. Some clinicians also prescribe 'near activities' in conjunction with patching but this was not found to be beneficial in a recent study[11].

Pharmacologic penalization of the sound eye is another commonly used modality to treat amblyopia. Atropine is the most commonly used pharmacologic agent. Dosing can be a drop in the sound eye daily, or on weekends only. A recent study showed results with weekend-only dosing to be similar to daily dosing for moderate amblyopes[12]. In children who wear hyperopic spectacles, atropine usage is sometimes combined with replacing the hyperopic lens over the sound eye with a plano lens. This was felt to 'enhance' treatment, but a recent study showed only a minimal benefit of this additional step in therapy[13].A common assumption is that atropine use in the amblyopic patient can only be effective if it induces a fixation switch. This assumption has been called into question by a recent study. Often the decision whether to treat the amblyopic child with patching or pharmacologic agents, is based on the practitioner's practice patterns and parental wishes.

A head-to-head study showed that 6 hours a day of patching therapy produced a slightly more rapid and beneficial effect than daily instillation of Atropine 1%, in moderate amblyopes younger than 7 years of age. However, the final difference at 6 months was not statistically significant and a parental questionnaire showed families preferred pharmacologic therapy over patching[14].

Other modalities of medical amblyopia management include optical penalization with an occlusive Bangerter filter placed on the glasses lens or the use of a high plus lens to blur the sound eye, as well as contact lenses used as occlusion or for blurring.

Dichoptic video games and dichoptic movies are being studied as potential novel therapies for amblyopia. PEDIG studies showed that patching was superior to the use of an earlier, less engaging, dichoptic falling blocks video game for amblyopia treatment [15] [16]. More recently, PEDIG showed that in children aged 7 to 12 years who received previous treatment for amblyopia other than spectacles, the dichoptic adventure video game Dig Rush showed no benefit to vision or stereoacuity after 4-8 weeks of treatment over spectacle use alone. [17]

A novel digital therapeutic using virtual reality (VR) headsets, Luminopia One, delivers dichoptic amblyopia therapy while providing an engaging patient experience. Therapeutic visual stimuli are presented using real-time modification of patient-selected, cloud-based video content (e.g., television shows or movies) within a head-mounted display. In a randomized clinical trial of 105 children aged 4-7 years across 21 sites with anisometropic or strabismic amblyopia, amblyopic eye visual acuity improved by 1.8 lines in the Luminopia One treatment group compared to 0.8 lines in the spectacles-alone control group. [18] On 2021 October, the FDA approved Luminopia One for "improvement in visual acuity in children with amblyopia, aged 4-7, associated with anisometropia and/or with mild strabismus,"

CureSight is a promising dichoptic treatment for amblyopia that uses eye-tracking to induce real-time blur around the fellow eye fovea in dichoptic streamed video content. CureSight (90 min/day, 5 days/week) was found to be non-inferior to patching (2 hours/day, 7 days/week) in a 16 week multicenter trial of 103 children 4 to < 9 years with anisometropic, small-angle strabismic or mixed-mechanism amblyopia. [19]

Medical follow up

Follow up during treatment is typically somewhere between every 1-3 months. When treatment is discontinued, follow-up is necessary to ensure there is no regression of effect[20].

Surgery

Amblyopia itself is not a surgical condition, but there are times when surgery may treat the underlying cause of the amblyopia. Refractive surgery may be used to correct anisometropia. However, refractive surgeries are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, USA) below 18 years of age. Eye muscle surgery can correct strabismus. Cataract, ptosis, vitrectomy, or corneal surgery may alleviate causes of deprivation.

Surgical follow-up

Even though surgery may be performed to alleviate some of the etiologies of amblyopia, most cases will still require follow-up to treat the amblyopia that is present. For example, in a child with strabismic amblyopia, eliminating the ocular misalignment does not automatically fully correct the amblyopia which resulted from the strabismus.

Complications

Overly aggressive amblyopia therapy (especially in younger patients) can produce reverse amblyopia of the sound eye. A new strabismus or a decompensation of an existing strabismus can also occur. Patches can be irritating to the skin, and the skin underlying the patch can become hypopigmented relative to the rest of the facial skin. There is also a potential social stigma associated with wearing the patch to school in some cases. Atropine use can cause side effects related to the use of this medication: flushing, rapid heart rate, mood changes (uncommon) and photophobia (common) would be examples of side effects occurring with the use of this medication. Reverse amblyopia can also occur with Atropine use as can decompensation of existing strabismus or development of a new strabismus. Cases of reverse amblyopia are infrequent and usually mild. Most cases resolve with discontinuation of treatment.

Prognosis

The keys to treatment success are younger age at detection/treatment, short course until intervention, and compliance with treatment. The effectiveness of intensive screening protocols to detect amblyopia at a young age has been shown to result in a better acuity of the amblyopic eye at age 7.5 years. Most patients do improve with treatment, but often residual amblyopia remains. With cessation of amblyopia treatment there is a risk of recurrence. In one study, the risk of recurrence was higher with better visual acuity at the time of cessation of treatment, a greater number of lines improved during the previous treatment, and a prior history of recurrence. Orthotropia or excellent stereoacuity at the time of patching cessation did not appear to have a protective effect on the risk of recurrence. In a prospective study of cessation of treatment in children aged 3 to <8 years with successfully treated amblyopia due to anisometropia, strabismus or both, the risk of amblyopia recurrence was found to be 24%. Patients treated with 6 to 8 hours of daily patching had a 4-fold greater odds of recurrence if patching was stopped abruptly rather than when it was reduced to 2 hours per day prior to cessation. Careful and prolonged follow-up during the amblyogenic years, is needed for all children who have been previously treated for amblyopia to prevent a recurrence. In general, the younger amblyopes are treated, the better the likelihood of improvement.

Most textbooks do not recommend trying amblyopia therapy in the second decade of life but some improvement can be obtained in few cases. A study of amblyopia therapy in children aged 7-17 years found that amblyopia improves to some degree with optical correction alone in about one fourth of patients. However most required additional treatment for amblyopia[21]. For patients aged 7 to 12 years, 2 to 6 hours per day of patching with near visual activities and atropine improved visual acuity even if the amblyopia had been previously treated. For patients 13 to 17 years, improvement was only noted in those children who had not been previously treated. The degree of improvement in these older children was much more modest than results from other studies of younger children, so the importance of early detection and treatment remains.

Studies have demonstrated that amblyopic children read significantly more slowly than controls, even when the vision in the amblyopic eye is only reduced to 20/30 vision.[22] [23] Amblyopia can also impact academic related fine-motor outcomes, such as multiple-choice answer completion time. [24]

Pertinent clinical trials

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigators Group Study (PEDIG) –or– Amblyopia Treatment Study

Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:268 | Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:603 | Ophthalmol 2003;110:2075 | J AAPOS 2004;8:420 | Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:437 | Ophthalmol 2006;113:895 | Ophthalmol 2006;113:904.

Objectives

The goal was to determine if correcting the refractive error alone can treat amblyopia, the benefits of patching, and the risks of recurrence after suspension of treatment. In addition, it wanted to know until what age can amblyopia be treated and the management with atropine and occlusion.

This trial tried to facilitate an evidence-based approach to the treatment of amblyopia.

Design

Clinical trials involving

- Observational study of spectacles alone for anisometropic amblyopia.

- Amblyopia treatment randomized to daily atropine to the fellow eye or at least 6 hours of patching per day.

- 2 concurrent randomized trials of patching, prescribed 2 hours/day versus 6 hours/day for moderate amblyopia and prescribed 6 hours/day versus full-time for severe amblyopia.

- Patching in older children: children randomised to receive optical correction ± patching for near activities.

- Recurrence of amblyopia: children treated with patching or atropine for at least three months with at least three lines of improvement were brought off therapy, and followed up for one year.

Moderate amblyopia was defined as 20/40 to 20/80. Severe amblyopia was defined as 20/100 to 20/400. Successful treatment was defined as the improvement of VA to within one line of the non-amblyopic eye. Recurrence of amblyopia was defined as a reduction in at least two lines after cessation of amblyopia therapy or when treatment was restarted at an investigator’s discretion.

Inclusion criteria were children less than seven years, BCVA in the better eye better than 20/40, and the amblyopic eye less than 20/40. Previous refractive error corrected for at least four weeks before the study.

Main outcome measures

Primary endpoint: BCVA.

Results

More than 4000 subjects have participated in 19 Amblyopia Treatment Studies (ATS). The main ones were:

- Observational study of spectacles alone for anisometropic amblyopia: 84 children, 3 to 6 years of age and VA from 20/40 to 20/250 at enrollment. 77% of the children improved at least 2 lines, and 27% showed resolution within 1 line of the fellow eye. Maximum improvement was achieved by 83% of subjects by 10 weeks, but some children improved for 30 weeks. Improvement was found in children with moderate and severe amblyopia. The key lesson was that spectacles are an effective initial tool in managing amblyopia.

- Amblyopia treatment randomized to daily atropine to the fellow eye or at least 6 hours of patching per day. 419 children, 3 to 6 years of age with amblyopia 20/40 to 20/100. VA improved in both groups at 6 months; during the initial treatment phase, the patching group did improve more quickly, but the atropine group caught up by 6 months. Thus, atropine and patching are effective in the treatment of amblyopia. Parental questionnaires found atropine to be better tolerated in terms of social stigma and compliance. The amblyopia treatment benefit persisted through age 10 years without a mean VA loss, but residual amblyopia remains in a large proportion of children. The mean amblyopic eye VA at 10 years was approximately 20/32, with 46% of amblyopic eyes 20/25 or better. After the initial 6-months, children were treated at the investigator's discretion with occlusion or atropine, and more than 85% of children continued to be prescribed treatment. So, amblyopia treatment is not a short-term task; it represents a long-term effort.

- 2 concurrent randomized trials of patching, prescribed 2 hours/day versus 6 hours/day for moderate amblyopia and prescribed 6 hours/day versus full-time for severe amblyopia in 3 to 6-year-olds children. 175 severe amblyopes were randomised to receive full-time patching vs. six hours/day patching for four months. 189 moderate amblyopes were randomised to receive either two or six hours a day of patching for four months. VA improved with both patching regimens without differences. Therefore, it is reasonable to initiate therapy with a lower dose and increase treatment intensity if the response is not good.

- Patching in older children: 507 children with amblyopia aged 7 to 18 were recruited and randomised to receive optical correction ± patching for near activities. There was a significant improvement in BCVA in those treated with patching in the 7-12 age group but not in the 13 -17 age group. When only the 13-17-year olds with no previous treatment for amblyopia were considered, there was an improvement in the patched group.

- Recurrence of amblyopia: 156 children who had been treated with patching or atropine for at least three months with at least three lines of improvement were brought off therapy at the investigator's discretion and followed up for one year. The average age was 5.9 years, and no child was older than eight. 21% of children experienced amblyopia recurrence, with 40% occurring within the first five weeks.

Limitations

Children younger than three were not included

Conclusions

Refractive correction alone may be effective in the treatment of amblyopia. There is no benefit in patching moderate amblyopes for longer than two hours and severe amblyopes for more than six hours per day. Children need close follow-up after discontinuation of occlusion therapy. There may be a benefit in treating amblyopia until 12 years of age. Teenagers with amblyopia who have never before received treatment may benefit from a trial of patching. There is no clinical difference in using atropine vs. patching in moderate amblyopes.

Pearls for clinical practice

Refraction helps amblyopia.

Moderate amblyopes can be treated using atropine or patching.

Public Health Implications of Amblyopia

1. Prevalence and Burden

- Affects 3–5% of children.

- Leading cause of preventable monocular visual impairment in children and young adults.

- Long-term effects on vision, education, fine motor skills, driving eligibility, and career options.

Amblyopia is among the most common causes of preventable monocular visual impairment in children and young adults. Global estimates suggest a prevalence between 1–5%, with variability based on study methodology, diagnostic criteria, and geographic region.[25] [26][27][28] In the United States, population-based studies have reported prevalence rates of approximately 2–3% in preschool- and school-aged children, representing a substantial number of children at risk for long-term vision impairment.[26] [27]

The burden of amblyopia extends beyond reduced visual acuity. Children with amblyopia demonstrate slower reading speeds, reduced stereopsis, and impaired fine motor skills compared to their peers, which may influence educational attainment and daily functioning.[29] [30][31] These functional limitations often persist into adulthood, contributing to restrictions in driving eligibility and occupational opportunities in careers that require optimal visual performance, such as aviation, military service, and law enforcement.[32] [33] [34] Furthermore, unilateral amblyopia is a lifelong risk factor for bilateral visual disability, as injury or disease in patients’ other eye can lead to profound vision loss. One population-based cohort study found that individuals with amblyopia had nearly double the risk of bilateral visual impairment later in life compared to those without amblyopia.[35]

2. Societal and Economic Impact

- Decreased productivity and quality of life due to lifelong vision loss.

- Cost burden of treatment, follow-up care, and long-term support services.

- Disparities in access to early screening and treatment (rural vs. urban, low-income communities).

Amblyopia imposes substantial societal and economic costs due to its lifelong impact on vision and function. Beyond the direct consequences of reduced acuity and stereopsis, amblyopia is associated with decreased productivity, lower educational outcomes, and diminished quality of life. [36] [37][38] Adults with amblyopia report greater visual task-related difficulties, including challenges in fine motor performance and driving, which can limit independence and employability.[37][38][39] These effects accumulate over time, contributing to broader workforce inefficiencies and reduced socioeconomic potential.

The economic burden of amblyopia encompasses both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include treatment expenses (glasses, patching, pharmacologic penalization, and, more recently, digital therapeutics), follow-up visits, and management of associated ocular conditions.[40] Indirect costs stem from lost productivity, restricted occupational opportunities, and long-term support services required for those who progress to bilateral visual impairment after fellow-eye injury or disease.[41] Cost-effectiveness studies have consistently demonstrated that preschool vision screening programs, particularly when combined with timely treatment, offer favorable economic value by reducing the prevalence of severe amblyopia and its downstream costs.[42] [43]

Importantly, disparities exist in access to both early screening and treatment. Children from rural and low-income communities are less likely to undergo vision screening and more likely to experience delayed diagnosis, leading to worse long-term outcomes.[44][45][46] Barriers include lack of awareness, limited availability of pediatric eye care providers, and inconsistent integration of vision screening into primary care and school-based health services. Addressing these inequities is central to reducing the overall societal burden of amblyopia.

Awareness and Early Detection Efforts

1. Vision Screening Programs

Early vision screening in preschool is a cornerstone of preventative care. Leading societies, including the American Academy for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS) and the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO), recommend red reflex testing at birth with urgent referral if abnormal, ocular health assessments at every well-child visit from 1 month to 4 years, and formal visual acuity testing beginning when children are cooperative (typically 3.5 to 4 years, no later than 5). Optional instrument-based screening is advised between 12-36 months and as an alternative to chart-based methods at ages 3 to 5 with continued screening every 1 to 2 years thereafter. Any failed or inconclusive screen should prompt referral for ophthalmologic evaluation. [47] The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) further recommends at least one vision screen between ages 3-5, recognizing the higher efficacy of intervention during this developmental window.

Despite these recommendations, gaps in access and follow-up remain. The disparity is greatest among low-income, uninsured, and minority populations. [48] In a study of 15 screening programs, fewer than half of children who failed a screen received a comprehensive eye exam in 11 of the programs, with inadequate information, transportation, cost and insurance barriers cited as key obstacles.[48] National data further show that only 63.5% of children aged 3-5 receive vision testing in the United States, with lower rates amongst those publicly insured (61.2%) and uninsured (43.3%). [49]These disparities underscore the need for improved referral verification systems, examined coverage policies, and integration of vision screening into broader preventive health services.

2. Public Awareness Campaigns

AAPOS and its nonprofit arm, the Children’s Eye Foundation, drive national-level outreach through initiatives like All Children See (ACS). ACS is a public service program launched in 2020 that matches children in need of comprehensive eye exams with volunteer pediatric ophthalmologists, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Prioritizing children who have failed vision screening, the program currently operates in 30 states and Washington D.C. and has over 100 participating specialists. These efforts are essential in preventing untreated amblyopia, amongst ma other eye conditions.[50]

AAO is also promoting amblyopia awareness through leadership initiatives and public health campaigns. One example was a multi-stakeholder collaboration in Florida that led to the declaration of an Amblyopia Awareness Month via a state resolution. The campaign organized high-visibility screening events and encouraged pediatricians, legislators, and advocacy groups to promote preschool vision screening. The initiative demonstrated how local efforts can be scaled to influence policy and shift public awareness on sight saving topics.[51]

Prevent Blindness America, a major public health advocate for children’s vision, publicly supports legislation such as the Early Detection of Vision Impairments (EDVI) Act, which aims to establish federally funded programs for vision screening, referral systems, and follow-up care. The EDVI has potential to fill critical gaps in current US vision care policy and bring coordinated attention to children’s vision on a national scale.[52] The organization also fosters family engagement and a support network through its program the eye patch club which supports children undergoing amblyopia patching therapy. The program not only promotes adherence to treatment through tools like calendars, a parent forum, and expert tips, but also builds a community network around one of the most common yet under-recognized childhood vision disorders.[53]

3. Digital Tools and Innovations

Mobile health technologies are broadening access and enhancing early detection of amblyopia and other visual impairments. Smartphone-based applications and telemedicine platforms provide a cost-effective, scalable approach, particularly for underserved and rural populations. Often leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning, these tools demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity for identifying refractive errors and strabismus in children. For instance, the GoCheck Kids app achieved 84% sensitivity and 86% specificity for detecting amblyopia risk factors in primary care, closely paralleling conventional screening modalities.[54] Teleophthalmology platforms further extend access by enabling remote interpretation of visual data, promoting timely intervention during early childhood when treatment is most affective.[55]

Portable photo-screeners such as the Spot Vision Screener and Plusoptix devices have also gained wide adoption among pediatricians, school nurses, and community health programs. Though limitations exists, these handheld devices capture binocular reflexes with seconds, allowing non-specialists to better detect amblyogenic factors such as anisometropia and media opacities to promptly direct referral for a comprehensive eye exam. [56][57] In community-based studies, photo-screener referrals demonstrated over 90% concordance with comprehensive eye examinations.[57] Their portability and ease of use make them valuable in both community and school-based initiatives. These emerging technologies are helping close critical gaps in childhood vision care by enabling earlier, more equitable detection, though challenges still remain.[57]

Policy and Advocacy Initiatives

1. National Screening Guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all children aged 3 to 5 years should undergo vision screening at least once to detect amblyopia or its risk factors, including strabismus, high or uncorrected refractive errors, anisometropia, and media opacities such as cataracts.[58] This recommendation was given a Grade B, as it is believed to have a moderate certainty of moderate benefit.[59] For children younger than 3 years, the USPSTF found the evidence insufficient to assess whether screening benefits outweigh the harms.[58] The American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus recommend starting vision screening in newborns, using age-appropriate methods such as red reflex testing, ocular alignment testing including the cover/uncover test and corneal light reflex, and visual acuity testing. [60] [61] Visual acuity is generally tested with vision charts for children older than 3 years. [61] Alternatives for children 12 months to 3 years old include photoscreening and handheld autorefraction.[61]

If abnormalities are found on vision screening, the child should be referred for a comprehensive ophthalmologic exam for diagnosis and treatment.

2. Insurance and Coverage

Under Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT), state Medicaid programs are required to cover vision screening and diagnostic services for children and adolescents. If a screening suggests a vision problem such as amblyopia, EPSDT mandates Medicaid coverage and state provision of necessary diagnostic and treatment services, including further testing and glasses, with “reasonable promptness”. Moreover, Medicaid states that each state must adopt a periodicity schedule for vision screening consistent with standards of medical practice. [62] Children can also be screened in between periodic screenings if a provider, parent, or professional involved in their development or education suspects a potential problem.[62] Regarding private insurance plans, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) states that vision screening services recommended by USPSTF with a Grade “A” or “B” recommendation, such as amblyopia screening, must be covered without cost sharing.[63] However, while pediatric vision care is covered under the ACA, everything other than vision screening can have copays, or be counted towards the deductible and/or covered with coinsurance, depending on the plan.[64]

There is a growing need for stronger advocacy to improve insurance coverage for effective amblyopia treatments, including both traditional and newer options. As discussed, while many children can access vision screening through Medicaid or private insurance, coverage for treatment after diagnosis is often inconsistent or insufficient. Essential interventions like occlusion therapy (eye patching), prescription glasses, or new FDA-approved digital therapies such as Luminopia One may not be fully covered, or are only reimbursed under limited conditions.

3. Legislation and Public Health Funding

Currently, 40 states mandate vision screening for school‐aged children in at least one grade.[65] However, a 2021 study stated that only 26 states have mandates for preschool vision screening.[66] The variability across states reflects a lack of unified policy for detecting amblyopia early, despite its known benefits when treated before the age of 7.

There is increasing advocacy to make amblyopia screening a routine part of pediatric preventive care, much like vaccinations or developmental screenings. The American Academy of Pediatrics includes vision screening in its Bright Futures periodicity schedule, starting at age 3.[67] Incorporating amblyopia screening into these broader guidelines supports uniform pediatric care standards and reduces missed opportunities for early detection.

To support wider implementation of amblyopia screening, several federal funding streams could be utilized, including the Title V Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Services Block Grant. Administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Title V is one of the largest federal funding sources dedicated to improving maternal and child health.[68] Funding could help expand preschool screening programs, train screeners, cover equipment costs (e.g., photoscreeners), and provide follow-up care for uninsured children. The HRSA has also previously funded pilot programs for vision screening in children under 5, especially in underserved communities.[69] Proposed legislative initiatives include the Vision Care for Kids Act of 2009 and the Early Detection of Vision Impairments in Children Act (EDVI), both of which aimed to secure federal grants in order to support and improve access to early childhood vision screening, treatment, follow-up, and education.[70] [71]

4. Health Equity Focus

Screening rates of Amblyopia are affected by race and socio-economic status. The National Health Interview survey from 2016-2017 reported that Hispanic children were less likely to have vision screenings (58.6%) compared to non-Hispanic white children (65.4%).[72] Children whose family’s income was equal to or greater than 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) were more likely to have their vision tested (67.7% vs 58.9%).[72] The higher the parent’s educational level, the more likely the child would have vision screening. Having private health insurance coverage (66.7%) had higher rates of getting vision screenings compared to children with public health insurance (61.2%) or uninsured.[72]

Hispanic, Black, and Asian children have been shown to have delays in receiving surgical treatment for amblyopia.[73] Black and Hispanic children as well as those children on Medicaid were more likely to have residual amblyopia compared to white children.[73] From this data it is clear that those people of color and of a lower socio-economic background are likely to have delayed diagnosis of amblyopia and worse outcomes because of the later diagnosis and more likely to have residual amblyopia.

Future Directions

Given amblyopia’s significant and lifelong societal and economic impacts, creating sustainable and effective evaluation and intervention programs is vital. [74][75][76] The future of amblyopia care depends on bringing early detection and treatment into settings that all children readily access. School and community-based programs already exist and must expand their capabilities to provide on-site eye exams to more children. In addition, incorporating the ability to provide treatment and prescription glasses in these spaces or creating strong connections to facilities with these capabilities can close major gaps in care, thus improving follow-up after failed screenings.[77] Beyond schools and community based programs, integrating these initiatives into pediatric care facilities and other public health organizations can expand the reach of screenings, ensuring early detection and intervention in as many children as possible.

Access to screening is imperative, but effective diagnostic tools and treatment strategies are equally key. Digital innovation has and continues to reshape both screening and therapy. Portable photo-screeners and smartphone-based tools with AI capabilities are increasing access to quality screening in primary care and underserved areas, becoming vital tools.[78][79][80][81] Newly FDA-cleared digital therapies such as Luminopia One and CureSight are also transforming home-based treatment by improving adherence and engagement among children who struggle with traditional patching methods.[82] Ensuring that these technologies are equitably available must be a priority to continue to improve outcomes and decrease the disease burden on patients and the system.

Wider and more effective screening and treatment options have created a future with significant promise for those at risk of amblyopia. To ensure their availability, future policy efforts should focus on standardizing preschool vision screening requirements across states, supporting school-based programs with sustainable funding, and building systems that track referral completion, ensuring patients are not lost to follow up. Collaboration between ophthalmology, pediatrics, and government and public health organizations will be key to ensuring that no child is missed due to geography, insurance status, or any other socioeconomic barrier.[75][83] Finally, creating a larger and stronger network of available providers is necessary, which would involve addressing the growing deficit of pediatric ophthalmologists, optometrists, and orthoptists that the system currently endures.[84]

The ultimate goal of all parties involved must be consistent. Efforts should work to make amblyopia a fully preventable cause of lifelong visual disability, which can be accomplished through earlier detection, equitable access to effective treatments, and modernized care delivery shaped around the individualized needs of each and every child.

Additional Resources

- AAPOS Frequently Asked Questions about Amblyopia

- Prevent Blindness America - Amblyopia

- Boyd K, Puente MA Jr. Amblyopia. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/amblyopia-6. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Boyd K, Lipsky SN. Depth Perception. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/anatomy/depth-perception-2. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Boyd K, Puente MA Jr. Lazy Eye (Amblyopia). American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/lazy-eye-amblyopia. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Boyd K, Puente MA Jr, Turbert D. Strabismus (Crossed Eyes). American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/strabismus-in-children-2. Accessed November 17, 2022.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Amblyopia. https://www.aao.org/education/image/amblyopia-3 Accessed February 26, 2025.

- ↑ Backman H. Children at risk of developing amblyopia: When to refer for an eye examination. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9(9):635-637. doi:10.1093/pch/9.9.635

- ↑ Wright KW and Spiegel PH. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 1st ed. pp 195-229. 1999.

- ↑ Magdalene D, Bhattacharjee H, Choudhury M, Multani PK, Singh A, Deshmukh S, Gupta K. Community outreach: An indicator for assessment of prevalence of amblyopia. Indian J Ophthalmol [serial online] 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 2];66:940-4. Available from: http://www.ijo.in/text.asp?2018/66/7/940/234966

- ↑ Simakurthy S, Tripathy K. Marcus Gunn Pupil. [Updated 2023 Feb 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557675/

- ↑ Bacal DA. Amblyopia Treatment Studies. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 15:432-436. 2004.

- ↑ Holmes JM, Beck RW, Repka MX, et al. The amblyopia treatment study visual acuity testing protocol. Arch Ophthalmol 2003, 119:1345-1353.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Treatment of bilateral refractive amblyopia in children three to less than 10 years of age. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144(4):487-96.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of prescribed patching regimens for treatment of severe amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology 2003;110:2075-2087.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of patching regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology 2003;121:603-611.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of near versus distance activities while patching for amblyopia in children aged 3 to less than 7 years. Ophthalmology 2008;115(11):2071-8.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of atropine regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Ophthalmology 2004;111(11):2076-85.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Pharmacologic plus optical penalization treatment for amblyopia: results of a randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127(1):22-30.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of atropine vs. patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120(3):268-278.

- ↑ PEDIG, Holmes JM, Manh VM, Lazar EL, et al. Effect of a Binocular iPad Game vs Part-time Patching in Children Aged 5 to 12 Years With Amblyopia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 Dec 1;134(12):1391-1400.

- ↑ PEDIG, Manh VM, Holmes JM, Lazar EL, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Binocular iPad Game Versus Part-Time Patching in Children Aged 13 to 16 Years With Amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018 Feb;186:104-115.

- ↑ PEDIG, Holmes JM, Manny RE, Lazar EL, et al. A Randomized Trial of Binocular Dig Rush Game Treatment for Amblyopia in Children Aged 7 to 12 Years. Ophthalmology 2019 Mar;126:456-466.

- ↑ Luminopia Pivotal Trial Group, Xiao S, Angejeli E, Wu HC, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Dichoptic Digital Therapeutic for Amblyopia. Ophthalmology 2022 Jan;129:77-85.

- ↑ Wygnanski-Jaffe T, Kushner BJ, Moshkovitz A, Belkin M et al, on behalf of the CureSight Pivotal Trial Group. An Eye-Tracking–Based Dichoptic Home Treatment for Amblyopia, A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology 2023;130:274-285.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Risk of amblyopia recurrence after cessation of treatment. J AAPOS 2004;8(5):420-8.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Randomized trial of treatment of amblyopia in children aged 7 to 17 years. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123(4):437-47.

- ↑ Kelly KR, Jost RM2 De La Cruz A, Birch EE. Amblyopic children read more slowly than controls under natural, binocular reading conditions. J AAPOS. 2015 Dec;19(6):515-20.

- ↑ Kelly KR, Jost RM, De La Cruz A, et al. Slow reading in children with anisometropic amblyopia is associated with fixation instability and increased saccades. J AAPOS. 2017 Dec;21(6):447-451.

- ↑ Kelly KR, Jost RM, De La Cruz A, Birch EE. Multiple-Choice Answer Form Completion Time in Children With Amblyopia and Strabismus. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018 Aug 1;136(8):938-941.

- ↑ Hashemi H, Pakzad R, Yekta A, et al. Global and regional estimates of prevalence of amblyopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Strabismus. 2018;26(4):168-183.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in African American and Hispanic children ages 6 to 72 months. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1229-1236.e1

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Backman H. Children at risk of developing amblyopia: When to refer for an eye examination. Paediatr Child Health. 2004 Nov;9(9):635-637. doi: 10.1093/pch/9.9.635. PMID: 19675853; PMCID: PMC2724129.

- ↑ Chia A, Dirani M, Chan YH, et al. Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in young Singaporean Chinese children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(7):3411-3417.

- ↑ Kelly KR, Jost RM, Dao L, et al. Reading in amblyopic children: A comparison of eye movements and reading speed in amblyopic and fellow eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(11):7558-7565.

- ↑ Kelly KR, Jost RM, De La Cruz A, Birch EE. Amblyopic children read more slowly than controls under natural, binocular reading conditions. J AAPOS. 2015;19(6):515-520.

- ↑ Webber AL, Wood JM, Gole GA, Brown B. The effect of amblyopia on fine motor skills in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(2):594-603.

- ↑ Jackson JL, Barnett S, Hay WW. Visual requirements for aviators: An evidence-based review. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006;77(11):1152-1159.

- ↑ O’Connor AR, Fawcett SL, Stager DR, Birch EE. Stereoacuity outcomes in children treated for infantile and accommodative esotropia. Strabismus. 2010;18(3):110-117.

- ↑ Kulp MT, Ciner E, Maguire M, et al. Uncorrected hyperopia and preschool early literacy: Results of the Vision in Preschoolers – Hyperopia in Preschoolers (VIP-HIP) Study. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(4):681-689.

- ↑ Rahi JS, Logan S, Timms C, Russell-Eggitt I, Taylor D. Risk, causes, and outcomes of visual impairment after loss of vision in the non-amblyopic eye: A population-based study. Lancet. 2002;360(9333):597-602.

- ↑ van Leeuwen R, Eijkemans MJ, Vingerling JR, et al. Risk of bilateral visual impairment in individuals with amblyopia: The Rotterdam Study. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):883-885.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Webber AL, Wood JM, Gole GA, Brown B. The effect of amblyopia on fine motor skills in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(2):594-603.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Carlton J, Kaltenthaler E. Amblyopia and quality of life: A systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(4):403-413.

- ↑ Kulp MT, Schmidt PP. Amblyopia effects on health-related quality of life in children. J AAPOS. 2016;20(6):478-482.

- ↑ Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial of atropine vs patching for treatment of moderate amblyopia: Follow-up at age 10 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(8):1039-1044.

- ↑ Rahi JS, Logan S, Timms C, Russell-Eggitt I, Taylor D. Risk, causes, and outcomes of visual impairment after loss of vision in the non-amblyopic eye: A population-based study. Lancet. 2002;360(9333):597-602.

- ↑ Carlton J, Karnon J, Czoski-Murray C, Smith KJ, Marr J. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening programmes for amblyopia and strabismus in children up to the age of 4–5 years: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12(25):iii, xi–194.

- ↑ Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Zhang X, et al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(12):1754-1760.

- ↑ Tarczy-Hornoch K, Varma R, Cotter SA, et al. Risk factors for decreased visual acuity in preschool children: The Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease and Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Studies. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(11):2262-2273.

- ↑ Harvey EM, Miller JM, Twelker JD, Davis AL. Reading fluency in school-aged children with bilateral astigmatism. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(2):118-125.

- ↑ Miller JM, Lessin HR; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Ophthalmology; American Academy of Ophthalmology; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Instrument-based pediatric vision screening policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):983-986.

- ↑ American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Vision Screening for Infants and Children: Joint Policy Statement. 2022. https://www.aao.org/education/clinical-statement/vision-screening-infants-children-2022

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Hutchinson, A. K., Morse, C. L., Hercinovic, A., Cruz, O. A., Sprunger, D. T., Repka, M. X., Lambert, S. R., Wallace, D. K., & American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus Panel (2023). Pediatric Eye Evaluations Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology, 130(3), P222–P270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.10.030

- ↑ Black, L. I., Boersma, P., & Jen, A. (2019). Vision Testing Among Children Aged 3-5 Years in the United States, 2016-2017. NCHS data brief, (353), 1–8.

- ↑ American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. All Children See. https://aapos.org/cefsandbox/what-we-do/all-children-see

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Leadership Development Program Advocacy Projects. https://www.aao.org/about/leadership-development/advocacy-projects

- ↑ Prevent Blindness. The Early Detection of Vision Impairments in Children Act (EDVI). https://advocacy.preventblindness.org/edvi-act-of-2024/

- ↑ Prevent Blindness. The Eye Patch Club. https://advocacy.preventblindness.org/the-eye-patch-club/

- ↑ Peterseim, M. M. W., Rhodes, R. S., Patel, R. N., Wilson, M. E., Edmondson, L. E., Logan, S. A., Cheeseman, E. W., Shortridge, E., & Trivedi, R. H. (2018). Effectiveness of the GoCheck Kids Vision Screener in Detecting Amblyopia Risk Factors. American journal of ophthalmology, 187, 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2017.12.020

- ↑ Rathi, S., Tsui, E., Mehta, N., Zahid, S., & Schuman, J. S. (2017). The Current State of Teleophthalmology in the United States. Ophthalmology, 124(12), 1729–1734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.026

- ↑ Ugurbas, S.C., Kucuk, N., Isik, I. et al. Objective vision screening using PlusoptiX for children aged 3–11 years in rural Turkey. BMC Ophthalmol 19, 73 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-019-1080-7

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Differences in ocular pigmentation may influence. Detection of amblyopia risk factors. Accessed 20,2025. https://www.aao.org/education/editors-choice/differences-in-ocular-pigmentation-may-influence

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Vision in Children Ages 6 Months to 5 Years: Screening | United States Preventive Services Taskforce. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org. Published September 5, 2017. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening

- ↑ Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Vision Screening in Children Aged 6 Months to 5 Years. JAMA. 2017;318(9):836. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.11260

- ↑ McConaghy JR, McGuirk R. Amblyopia: Detection and Treatment. American Family Physician. 2019;100(12):745-750. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/1215/p745.html

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 AAPOS and AAO Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Vision Screening for Infants and Children - 2022. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published October 1, 2022. https://www.aao.org/education/clinical-statement/vision-screening-infants-children-2022

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Vision and Hearing Screening Services for Children and Adolescents | Medicaid. Medicaid.gov. Published 2022. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/early-and-periodic-screening-diagnostic-and-treatment/vision-and-hearing-screening-services-children-and-adolescents

- ↑ Preventive Services Covered by Private Health Plans under the Affordable Care Act | KFF. kff.org. Published February 28, 2024. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/preventive-services-covered-by-private-health-plans/

- ↑ Norris L. How is vision care covered under Obamacare? healthinsurance.org. Published December 18, 2018. https://www.healthinsurance.org/faqs/how-is-vision-care-covered-under-the-affordable-care-act/

- ↑ Children’s Vision Screening Requirements by State - Prevent Blindness. preventblindness.org. Published 2016. https://preventblindness.org/vision-screening-requirements-by-state/

- ↑ Ambrosino C, Dai X, Aguirre BA, Collins ME. Pediatric and School-Age Vision Screening in the United States: Rationale, Components, and Future Directions. Children (Basel). 2023;10(3):490-490. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030490

- ↑ American Academy of Pediatrics. Preventive Care/Periodicity Schedule. Aap.org. Published February 6, 2026. https://www.aap.org/en/practice-management/care-delivery-approaches/periodicity-schedule/?srsltid=AfmBOopTQVh8mYwCyrxk5jlb22dxpPgxDgN0RhO_IXjP1Yrt0sicX4q4

- ↑ Explore the Title V Federal-State Partnership. mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov. Published 2023. https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/

- ↑ Vision Screening in Young Children Program | HRSA. Hrsa.gov. Published 2021. https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/HRSA-21-033

- ↑ Vision Care For Kids Act of 2009. davisvision.com. Published 2009. https://cvw1.davisvision.com/forms/staticfiles/english/kidsact_2009.pdf

- ↑ Early Detection of Vision Impairments for Children (EDVI) Act of 2024 . advocacy.preventblindness.org. Published February 28, 2024. https://advocacy.preventblindness.org/edvi-act-of-2024/

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Black L.I., Boersma P., Jen A.: Vision testing among children aged 3-5 years in the United States, 2016-20172019.NCHS Data Briefpp. 1-8. (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db353-h.pdf)

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Rajesh A.E., Davidson O., Lacy M., et. al.: IRIS® Registry Analytic Center Consortium. race, ethnicity, insurance, and population density associations with pediatric strabismus and strabismic amblyopia in the IRIS® registry. Ophthalmology 2023; 130: pp. 1090-1098.

- ↑ van Leeuwen R, Eijkemans MJ, Vingerling JR, et al. Risk of bilateral visual impairment in individuals with amblyopia: The Rotterdam Study. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):883-885.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Webber AL, Wood JM, Gole GA, Brown B. The effect of amblyopia on fine motor skills in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(2):594-603.

- ↑ Carlton J, Kaltenthaler E. Amblyopia and quality of life: A systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(4):403-413.

- ↑ Hutchinson, A. K., Morse, C. L., Hercinovic, A., Cruz, O. A., Sprunger, D. T., Repka, M. X., Lambert, S. R., Wallace, D. K., & American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus Panel (2023). Pediatric Eye Evaluations Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology, 130(3), P222–P270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.10.030

- ↑ Peterseim, M. M. W., Rhodes, R. S., Patel, R. N., Wilson, M. E., Edmondson, L. E., Logan, S. A., Cheeseman, E. W., Shortridge, E., & Trivedi, R. H. (2018). Effectiveness of the GoCheck Kids Vision Screener in Detecting Amblyopia Risk Factors. American journal of ophthalmology, 187, 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2017.12.020

- ↑ Rathi, S., Tsui, E., Mehta, N., Zahid, S., & Schuman, J. S. (2017). The Current State of Teleophthalmology in the United States. Ophthalmology, 124(12), 1729–1734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.026

- ↑ Ugurbas, S.C., Kucuk, N., Isik, I. et al. Objective vision screening using PlusoptiX for children aged 3–11 years in rural Turkey. BMC Ophthalmol 19, 73 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-019-1080-7

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Differences in ocular pigmentation may influence. Detection of amblyopia risk factors. Accessed 20,2025. https://www.aao.org/education/editors-choice/differences-in-ocular-pigmentation-may-influence

- ↑ American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. All Children See. https://aapos.org/cefsandbox/what-we-do/all-children-see

- ↑ Koc I, Bagheri S, Chau RK, et al. Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Digital Therapeutics for Amblyopia. Ophthalmology. 2025;132(6):654-660. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2024.12.037

- ↑ Siegler NE, Walsh HL, Cavuoto KM. Access to Pediatric Eye Care by Practitioner Type, Geographic Distribution, and US Population Demographics. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024;142(5):454. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2024.0612

- Williams C, Northstone K, Harrad RA, et al. Amblyopia treatment outcomes after screening before or at age 3 years:followup from randomized trial. BMJ 2002; 324:1549-1551.

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Patching vs atropine to treat amblyopia in children aged 7 to 12 years: a randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126(12):1634-1642.