Animal-Induced Ocular Trauma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Ocular trauma is a significant cause of blindness. Of the about 55 million eye injuries that occur worldwide each year, nearly 19 million cause blindness or low vision.[1] Various aspects of the diagnosis and management of ocular trauma are detailed in multiple EyeWiki pages describing general ocular trauma, penetrating and perforating injuries, and anterior segment trauma.[2][3][4] Eye injuries caused by animal traumas comprise a small proportion, yet they may have devastating consequences, such as keratitis, cataract, endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, and evisceration and enucleation.[5] Prompt recognition and appropriate management of these traumas are therefore needed. This EyeWiki page is dedicated to the unique considerations for ocular trauma caused by animals.

Animal-induced ocular trauma occurs through many mechanisms and has a wide range of presentations. Animals may cause eye injuries through defensive pecking, predatory bites, startle-induced kicks, or venomous stings. Animal beaks, claws, teeth, and barbs may cause eye injuries, which present with a broad spectrum of patterns, including orbital or periocular trauma (including eyelid lacerations involving the margin or canalicular system), puncture wounds, crush injuries, tissue avulsion, combined eyelid-globe injuries, conjunctival or scleral lacerations, and globe rupture and penetration. Certain animal-specific mechanisms can lead to unique complications, such as venom-induced tissue necrosis (e.g., snakes, spiders), high-velocity talon injuries (raptors), and globe dislocation from large mammal kicks.

Understanding the mechanism, anatomical involvement, and species-specific risks is essential for optimizing outcomes in animal-induced ocular trauma. While the general principles of ocular trauma management apply, species-specific and pattern-specific considerations are critical. These may include unique infection risks and toxicology considerations, determining whether the animal was rabid, potential for multi-trauma, and the mechanical trauma properties of the causative animal. In addition, the initial wound cleaning, appropriate rabies prophylaxis, and potential animal containment or euthanization (contingent upon individual circumstances and local laws) should be considered.

This article starts with the general considerations for animal-induced ocular trauma. These considerations are drawn from universally applicable principles for ocular trauma and from unique considerations when such trauma involves an animal. The second part of the article summarizes the current state of the literature for traumas involving individual classes and species of animals (Table 1).

| Animal Category | Examples |

| Domestic mammals

High frequency of injuries; common in ophthalmic emergency visits |

Cats, dogs, horses, cattle/goats/sheep |

| Wild mammals

Lower frequency; higher severity and infection risk |

Rodents (rats, mice), raccoons, deer, bats |

| Birds

High risk of penetrating injuries and globe rupture |

Owls, roosters, cranes, ostriches |

| Reptiles and amphibians

High contamination risk, crushing and biting injuries. Risk of venomous injury |

Snakes (venomous vs non-venomous), toads, and frogs |

| Marine Animals

Often overlooked; high toxic/infectious potential |

Stingrays, jellyfish toxins, coral, shellfish |

| Insects & Arthropods

Functionally and clinically distinct; includes unique mechanisms |

Caterpillars, spiders, beetles, millipedes, bees, fly larvae (maggots) ticks, ants |

Table 1. Animal culprits contributing to ocular trauma.

General Management Considerations

Initial evaluation and immediate care should include:

- Comprehensive history and ocular and periocular examination, assessment of visual acuity, and anterior and posterior segment evaluation should be performed. If dictated by the clinical scenario, perform a Seidel test to detect aqueous leak. Check intraocular pressure only if the globe is intact.

- Identify the insulting species, explore the possibility of species-specific bacterial infection, note the extent and depth of the injury, consider irrigating contaminated wounds or venom, consider pain control, avoid pressure on the globe, and apply globe protection. Systemic prophylactic antibiotics (species-specific: cat/dogs: amoxicillin-clavulanate or fluoroquinolone; Marine: doxycycline + cephalosporin or fluoroquinolone; reptile: broad-spectrum coverage, coverage for Salmonella) should be considered to cover likely pathogens (Table 2).

| Animal | Pathogens |

| Dogs/cats | Pasteurella, Capnocytophaga |

| Rodents | Streptobacillus spp. |

| Birds | Chlamydia psittaci (rare), polymicrobial infection |

| Reptiles | Salmonella, Aeromonas |

| Marine animals | Vibrio, Mycobacterium marinum, Aeromonas |

| Insects/arthropods | secondary cellulitis, anaphylaxis |

Table 2. Species-specific infections risk.

Imaging studies

Consider orbital CT and B-scan ultrasonography (if not contraindicated otherwise), depending on the clinical scenarios, especially when globe rupture or intraorbital foreign bodies are suspected.

Prophylaxis

Skin wounds should be adequately cleaned and irrigated to remove retained organic material. Exposed foreign bodies should be removed if indicated and appropriate. Appropriate systemic and topical antibiotics, tetanus vaccination, venom management, and rabies prophylaxis should be provided as indicated.

Surgical planning

Timely intervention for globe repair, retained organic foreign body removal, eyelid reconstruction, or orbital fracture fixation, with attention to the unique injury mechanism.

Other considerations

Consider microbiological sampling and cultures to guide subsequent antimicrobial therapy. Consider early involvement of other specialties (ENT, OMFS, infectious disease) when multi-system trauma or unusual pathogens are suspected. Culture of vitreous is the gold standard for bacterial endophthalmitis, but aqueous samples should also be collected if a specific clinical scenario dictates.[6]

Prevention should include public education on animal handling. Such education should cover protective eyewear when working with livestock or birds and proper restraint of pets, and awareness of venomous species.

The sections below will describe the features unique to different animal culprits. Each animal may induce injury through a unique mechanism, introduce unique pathogens, and require different diagnostic workup and management. Clinicians may use this resource as a reference for managing these potentially devastating injuries and modify their approach considering the specific ocular injury.

Domestic Animals

Cats

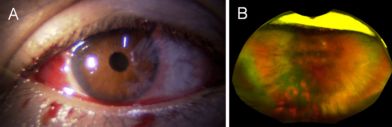

Many households own cats as domestic pets, making individuals especially susceptible. Cat injuries to the eye may be induced by several mechanisms, including cat scratches or cat bites. One case of vitreous hemorrhage induced by a cat forepaw has been reported (Figure 1), highlighting that seemingly benign interactions may cause significant eye injury.[7]

Sharp teeth and claws of a cat can easily cause corneal lacerations and globe punctures. A seemingly innocent eyelid skin scratch or puncture induced while playing with a cat may be a sign of deep and more involved globe laceration or penetration. It is important to perform a Seidel test in patients with cat-induced eye injuries to detect small puncture wounds. A positive Seidel test indicates an open globe injury, necessitating prompt surgical repair and antibiotic prophylaxis.

Cat mouths and claws carry numerous pathogens with high bacterial load. Full-thickness globe laceration commonly induces endophthalmitis associated with pathogens including Pasteurella, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Bacillus, Capnocytophaga, and Propionibacterium.[5] Pasteurella multocida is an especially common culprit.[5] Cats are also known to harbor Bartonella, although direct inoculation of the eye with Bartonella is infrequently reported. More commonly, the eye is affected by Bartonella via disseminated cat-scratch disease from a separate non-ocular site.[8]

When the organism is not yet known, endophthalmitis is typically treated broadly with intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime. This regimen generally covers the aforementioned pathogens. However, it is important to perform cultures so that antimicrobials can be tailored appropriately. Bacteria, and rarely fungi,[9] can be implicated, so both bacterial and fungal cultures should be considered. Systemic antibiotics should be initiated for open globe injuries.

The prognosis of these injuries varies widely, with final visual acuity ranging from 20/20 to evisceration.[5]

While rabies is more commonly transmitted by wild animals, domesticated cats may carry it if unvaccinated.[10] Therefore, rabies post-exposure prophylaxis may be required.

Dogs

Ocular trauma from dogs typically results from bites, scratches, or blunt impact. While facial and orbital soft tissue injuries are common, damage to the globe itself is less frequent but carries high morbidity.[11] The demographic most at risk is children, often involving a family pet.[11] Mechanisms include penetrating injuries from canine teeth, which can cause corneoscleral lacerations, or blunt force from a paw or snout, leading to hyphema, lens subluxation, or globe rupture.

Initial evaluation must rule out life-threatening injuries or orbital fractures. Ophthalmic examination focuses on visual acuity, pupillary reactions, and globe integrity. Signs of penetrating trauma include a peaked pupil, shallow anterior chamber, iris prolapse, and positive Seidel test. Blunt trauma may show corneal edema, hyphema, or vitreous hemorrhage. Intraocular pressure measurement must be deferred if rupture is suspected.

Corneal injuries range from superficial abrasions to full-thickness perforations. Even minor defects pose a risk by allowing highly virulent dog saliva pathogens (C. canimorsus and P. multocida) entry.[12][13] This can rapidly cause severe infectious keratitis (corneal ulceration) and stromal melt. Any corneal injury necessitates a high index of clinical suspicion and immediate prophylactic systemic antibiotic coverage to prevent endophthalmitis.

Dog bite endophthalmitis is a rare but a devastating infection driven by the virulence of pathogens such as C. canimorsus.[13] This pathogen causes endophthalmitis with a poor visual prognosis and even systemic sepsis.[14] The high infection rate and aggressive nature require immediate, aggressive systemic antibiotics (often Amoxicillin-clavulanate) and a low threshold for early vitrectomy.[15]

Ruptured globe injuries from dog bites are rare (approximately 2%) but catastrophic, typically affecting children.[11] When globe rupture occurs, the injury may be immediately complicated by introducing virulent organisms, requiring urgent primary surgical repair combined with aggressive systemic antibiotic therapy.

As with other animal-induced ocular trauma, microbiological assessment is critical. Cultures of the wound and intraocular fluids (aqueous or vitreous) must be obtained. The oral flora of dogs presents a unique risk for fulminant endophthalmitis, specifically from C. canimorsus and P. multocida.[12][13] Domesticated dogs may carry rabies if unvaccinated, and rabies post-exposure prophylaxis should be considered.[10]

Additional information about periocular dog bites is described in a separate EyeWiki.[16]

Horses

Ocular injuries caused by horses are often severe, due to the large size and power of the animal. These injuries typically involve blunt force, such as a kick or head collision, which can cause severe damage such as globe rupture and orbital fracture. Horse bites can also cause lacerations, and horse manes and tails can induce corneal scratches.

In one study, the most common mechanism of equestrian-related eye injuries was a horse kick, followed by falls from a horse.[17] The most common injury type in this study was an orbital fracture (58%), followed by eyelid/periocular lacerations (16%), traumatic optic neuropathy (5%), corneal abrasions (5%), and open globe injuries (3%).[17]

Endophthalmitis associated with horse-induced trauma is rarely reported. One case of endophthalmitis due to a horse's tail injury was caused by Enterococcus casseliflavus, an organism found in horse manure.[18]

Cattle

Farmers and ranchers are especially susceptible to ocular injuries from cattle. Cow horn injuries are one of the most devastating ocular traumas, as the pointed tip can create a forceful impact resulting in irreparable globe ruptures and lacerations that end up with evisceration.[19] Elderly farmers are particularly at risk, and this may be due to slower reflexes or decreased alertness to changes in animal behavior.[20] In order to prevent these types of injuries, safety glasses may be useful.[20] Some farmers also coagulate the calves' horns shortly after birth to prevent their development.[20] In addition to cow horns, eyes can be injured by trauma from cattle hoofs or being thrown/trampled.

During milking or handling, cattle tails can cause corneal abrasions. In a rare case, a farmer's eye was traumatized by a cow tail's sweep, resulting in Listeria endophthalmitis.[21] This case was successfully treated with linezolid.[21]

Unfortunately, many individuals affected by cattle injuries live in rural settings, where access to eye care is limited. A major barrier is the need to travel extensive distances to access an eye specialist.[22] Delayed management may result in a more guarded prognosis.

Goat and Sheep

Like cattle, goats can cause eye injuries by horn thrust. The horn can act as a hook and induce extraocular muscle avulsion.[23] Horn injuries can also penetrate the eye, causing globe rupture and possibly endophthalmitis.

Sheep can also induce horn injuries, and bighorn sheep may cause trauma when engaging in headbutting.[24] Male sheep (rams) in particular engage in forceful headbutting to establish dominance. This blunt force trauma can cause periorbital contusions, orbital fractures, and damage to internal structures.

Wild Mammals

Rodents

Rat bite injuries are rare but severe, potentially causing orbital cellulitis and significant loss of eyelid tissue.[25] Rat bites may involve the face, especially when the victim is sleeping.[25]

Mice bites can also affect the face and eye. Prenatally, mice secretions can induce eye disease in the form of congenital lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection.[26] This occurs when mothers are exposed to this virus through mice secretions, and the virus is transmitted transplacentally to the fetus.[26] LCMV can infect the fetus's retina, causing chorioretinal scarring and vision loss.[26]

Raccoons

A raccoon's sharp claws and teeth can cause severe penetrating injury to the globe and periocular tissue. A direct scratch or bite can lacerate the cornea. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis must be considered, in addition to appropriate wound cleaning, because raccoon bites carry a high risk of rabies. Rabies is generally fatal, but rabies vaccine can prevent 99% of deaths if administered promptly.[10]

Deer

Deer are powerful animals, and eye injuries caused by deer can be very severe. Antlers can act as spears, causing penetrating trauma to the eye. Hoof kicks and head butting can also cause severe blunt force trauma. Such globe ruptures usually end up with irreparable eye injuries and loss of vision, as is the case with ocular injuries caused by other large mammals.

Bats

Eye injuries from bats are rare. A case has been reported in which a patient was struck by a flying bat. A foreign body from the bat's claw entered the patient's cornea, causing localized keratitis and anterior uveitis.[27]

As with raccoons, bats carry a high risk of transmitting rabies, and rabies post-exposure prophylaxis should be strongly considered.

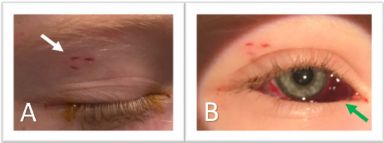

Birds

Ocular trauma caused by birds is uncommon but can be a potentially serious injury. It often results from bird pecking or clawing of the ocular or periocular area, when open-globe injuries are a significant concern, as the sharp beaks and claws can cause a full-thickness laceration (Figure 2).[28] However, bird injuries may also result from blunt force, causing globe rupture. One reported case described a patient who was kicked by an ostrich, causing extensive facial lacerations, orbital involvement, and blunt ocular trauma with hyphema.[29]

While any bird can potentially cause injury, one source suggests that most human eye bird injuries are caused by owls and roosters.[30] Interestingly, it is suggested that the bird's attention is directed toward the eye due to its target-shaped cornea and color contrast.[30] These injuries are more likely to occur in the spring season, and curved beaks tend to cause more damage than straight beaks.[30]

Children between the ages of 1 and 12 years are among the most commonly affected, likely due to their natural curiosity.[30] It is therefore important for parents to supervise their children when in proximity to birds.

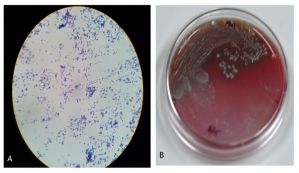

Endophthalmitis is a feared complication of bird injuries, especially bird pecking injuries, in which a long beak can cause deep penetration. For examples, there has been reports of one crane pecking injury and a rooster pecking injury caused endophthalmitis via beta and alpha hemolytic streptococci, respectively (Figure 3).[31][32]

Reptiles and Amphibians

Snake Venom Ophthalmia

Snake venom ophthalmia is a type of envenoming caused by spitting elapids, such as cobras, that can eject venom into the eyes of prey or predators.[33] Cobras can spit venom up to 8-12 feet away.[33]

Snake-venom ophthalmia often presents with painful, blurry vision, blepharospasm, conjunctival congestion, corneal epithelial defects, and chemosis.[33] However, the cornea is usually protected from permanent stromal opacification.[33] Systemic effects are uncommon.[33]

Management includes copious irrigation as early as possible.[33] Prophylactic topical antibiotics may be started to prevent keratitis.[33] Interestingly, heparin has been used to treat snake venom ophthalmia by inactivating the cardiotoxin present in the venom.[33]

Topical corticosteroids are contraindicated because they enhance the corneal collagenase activity of the venom, which may worsen corneal melting.[33] Additionally, antivenom is not recommended due to a lack of efficacy.[33]

Snake Bites

Snake bites to the eye have also been reported (Figure 4). These injuries may release toxins, causing airway edema, thus monitoring vital signs is critical.[35]

In one report, nonvenomous snake bites resulted in excellent visual prognosis (20/40 or better), while venomous snake bites resulted in no light perception in three out of three cases.[34] Therefore, the venomous or nonvenomous nature of the snake should be identified, as it is significantly correlated with visual prognosis.

Common Toad Poison

The common toad produces bufotoxin, an inhibitor of Na+/K+ ATPase activity.[36] Na+/K+ ATPase is important for the cornea, ciliary body, and iris, so exposure to bufotoxin can induce corneal dysfunction, impaired vision, as well as potent and immediate hypotonia.[36]

One report described a case of hypotonia and reduced vision following a spray to the eye by a common toad.[36] Eyes were washed with saline and topical antibiotics were administered.[36] Intraocular pressure returned to normal after a few hours, accompanied by improved vision.[36]

Toxic Keratopathy from Frog Saliva

Toxic keratopathy by corneal exposure to frog saliva has been reported.[37] Corneal punctate epitheliopathy, stromal edema, and Descemet folds were observed.[37] After irrigation, the clinical picture improved significantly on the second day of topical dexamethasone and ofloxacin.[37]

Marine Animals

Stingrays

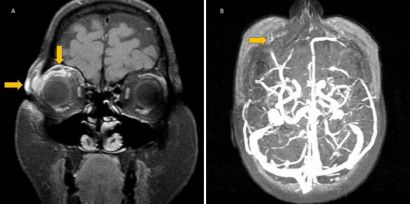

Stingray tails may cause significant ocular injury. The stingray's barbed tail spine can penetrate into soft tissue, causing damage via physical trauma, the venomous nature of the spine, and inoculation by marine bacteria.[38] Therefore, empiric antibiotics should be initiated. One report described a stingray tail injury that caused orbital cellulitis and superior optic vein thrombosis (Figure 5), so these complications should be kept in mind as well.[38]

Jellyfish Toxins

Jellyfish stings occur when victims contact the tentacles of the jellyfish which contain toxin-coated capsules from intracytoplasmic organelles called nematocysts.[39] Jellyfish stings to the eye commonly cause a toxic keratoconjunctivitis and present with severe ocular pain and photophobia.[39]

The most common clinical features of ocular jellyfish stings are the following: pain, conjunctival injection, corneal lesions, and photophobia.[39] Jellyfish have also been documented to cause periorbital edema, mydriasis, and iritis.[39][40] Examination may reveal thread-like foreign bodies embedded in the cornea which represent nematocyst tubules.[39] Initial treatment is copious irrigation with isotonic saline followed by removal of nematocysts under slit-lamp guidance. Treatment reported in the literature includes topical cycloplegics, topical steroids, topical antibiotics, and removal of nematocysts.[39] Symptoms are typically self-limited and prognosis is favorable.[39]

Coral

Palytoxin keratitis/keratoconjunctivitis (coral keratitis) is described in a separate EyeWiki.[41]

Shellfish

The most common cause of Vibrio conjunctivitis/keratitis is ocular trauma by shellfish, who transmit the pathogen through contaminated water.[42] Vibrio ocular inoculation may progress to endophthalmitis.[42] The most common species culprits in Vibrio ocular infections are V. vulnificus, V. alginolyticus, and V. parahaemolyticus.[42] V. vulnificus is the most virulent member of the Vibrio family, and although ocular infection may require prolonged treatment, one case found a rapid and successful response to hourly topical treatment with ciprofloxacin, Neosporin, and fortified vancomycin.[43] The final visual outcome was 20/20.[43]

Insects and Arthropods

Bee Injuries

Ocular bee injuries have been described in a separate EyeWiki.[44]

Ophthalmia Nodosa from Caterpillars and Tarantulas

Ophthalmia nodosa is a specific type of injury induced by the tiny, barbed hairs of certain insects, like caterpillars and tarantulas.[45] It is a severe inflammatory condition. Its pathology is further described in a separate EyeWiki.[46]

Nairobi Eye from Paederus Beetles

Paederus beetles are nocturnal predators common in humid climates.[47] Crushing of the beetle releases a fluid containing pederin, which can cause periorbital dermatitis with or without keratoconjunctivitis.[48] This ocular involvement is known as "Nairobi Eye."

Patients typically have continuous pain from onset.[48] Erythema develops within 24 hours and lasts about 48 hours.[48] Moderate or severe cases can progress to neuralgia and marked erythema, followed by a vesicular stage.[48] The vesicles are typically linear and gradually enlarge, followed by a squamous stage and scarring.[48]

The pederin toxin is a weak base.[48] The toxin is unable to permeate past the cornea; thus, damage does not typically extend to deeper structures.[48] Complications of the disease include keratitis secondary to mechanical trauma, as well as post-inflammatory skin hyperpigmentation in the periorbital area.[47][48]

Management includes immediate washing of the affected area. Topical corticosteroids, topical antibiotics, analgesics, and lubricating drops can be used for conjunctival and corneal injuries.[48] Periorbital lesions can be managed with antibiotic and steroid eye ointments, along with oral analgesics and antihistamines.[48]

Bombardier Beetle Burns

While extremely rare, bombardier beetles may induce ocular injuries. These beetles live in a variety of ecosystems and when threatened, they release a foul-smelling, hot liquid primarily derived from hydroquinone and hydrogen peroxide.[49] One article reported a case of a corneal chemical erosion caused by a bombardier beetle, which resolved fully with topical antibiotics and steroids.[49]

Millipede Burns

Giant millipedes possess a defense mechanism that involves spraying caustic substances.[51] Upon contact with the eye, these can cause periorbital edema, conjunctivitis, and keratitis.[51] While blindness is a potential complication, it is extremely rare.[51] Periorbital edema generally resolves within one week, conjunctivitis within one week, and keratitis by day 10.[51] Residual depigmentation may ensue.[51] Standard management includes irrigation, fluorescein eye drops to evaluate for corneal damage, control of inflammation, and topical antibiotics and corticosteroids.[51]

Ophthalmomyiasis from Fly Larvae

Ophthalmomyiasis, or ocular invasion by fly larvae (maggots), has been described in a separate EyeWiki.[52]

Ticks

Tick infestation of ocular tissues is rare. When affecting the eyelids (Figure 6), they can be removed safely with blunt forceps.[50] Ticks are hosts to a variety of systemic diseases. Therefore, in any tick infestation, additional testing for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Lyme disease, tularemia, and Q fever should be performed.[50]

Ants

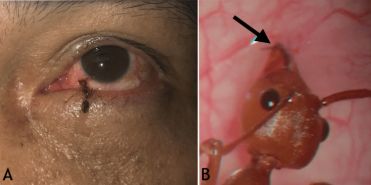

Ant-related ocular injuries may require surgical excision, as the mandibles can deeply embed the ant into the conjunctiva (Figure 7).[53] Possible chemical involvement should be considered; for example, the Asian weaver ant is known to secrete formic acid, which can cause inflammation and irritation.[53] Therefore, irrigation and pH assessment should be considered, in addition to antimicrobials and anti-inflammatory agents.[53]

References

- ↑ Négrel AD, Thylefors B. The global impact of eye injuries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5(3):143-169. doi:10.1076/opep.5.3.143.8364

- ↑ Patel A, Al-Aswad L, Legault G, et al. Ocular Trauma: Acute Evaluation, Cataract, Glaucoma. EyeWiki. August 5, 2024. https://eyewiki.org/Ocular_Trauma:_Acute_Evaluation,_Cataract,_Glaucoma

- ↑ Chuter B, Fowler B, Mukit F, et al. Ocular Penetrating and Perforating Injuries. EyeWiki. November 4, 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Ocular_Penetrating_and_Perforating_Injuries

- ↑ Patel A, Mehta A, Halfpenny C, et al. Anterior Segment Trauma: Evaluation, Considerations and Initial Management. EyeWiki. August 5, 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Anterior_Segment_Trauma:_Evaluation,_Considerations_and_Initial_Management

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Gao AY, Naravane AV, Simmons MA, et al. Fulminant endophthalmitis after open globe injury by cat claw: two case reports and literature review. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2025;15(1):41. doi:10.1186/s12348-025-00487-5

- ↑ AlBloushi AF, Ajamil-Rodanes S, Testi I, Wagland C, Grant-McKenzie N, Pavesio C. Diagnostic value of culture results from aqueous tap versus vitreous tap in cases of bacterial endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106(6):815-819. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-318916

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hasegawa D, Nishijima Y, Mimura T. Vitreous Hemorrhage Following Blunt Ocular Trauma by a Cat’s Forepaw: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2025;17(8):e89324. doi:10.7759/cureus.89324

- ↑ Amer R, Tugal-Tutkun I. Ophthalmic manifestations of bartonella infection. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28(6):607-612. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000419

- ↑ Emmaneerat N, Uthaithammarat L, Satitpitakul V, Kongwattananon W. First Case Report Of Letendraea helminthicola Endophthalmitis After Penetrating Ocular Trauma from a Cat Scratch. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. Published online October 16, 2025:1-4. doi:10.1080/09273948.2025.2569721

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Liu C, Cahill JD. Epidemiology of Rabies and Current US Vaccine Guidelines. R I Med J 2013. 2020;103(6):51-53.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Prendes MA, Jian-Amadi A, Chang SH, Shaftel SS. Ocular Trauma From Dog Bites: Characterization, Associations, and Treatment Patterns at a Regional Level I Trauma Center Over 11 Years. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(4):279-283. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000501

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Talan DA, Citron DM, Abrahamian FM, Moran GJ, Goldstein EJ. Bacteriologic analysis of infected dog and cat bites. Emergency Medicine Animal Bite Infection Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):85-92. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901143400202

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Muen WJ, Bal AM, Wheelan S, Green F. Bilateral endophthalmitis due to dog bite. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(7):1420-1421. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.02.016

- ↑ Łątkowska M, Gajdzis M, Turno-Kręcicka A, et al. Sudden Vision Loss as the First Sign of Sepsis-Bilateral Endogenous Endophthalmitis of Uncommon Capnocytophaga canimorsus Etiology. Med Kaunas Lith. 2024;60(6):896. doi:10.3390/medicina60060896

- ↑ Bhagat N, Nagori S, Zarbin M. Post-traumatic Infectious Endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(3):214-251. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2010.09.002

- ↑ Phelps P, Murchison A, Justin G, Yen M, Ahmad M, Brundridge W. Dog Bites (periocular). EyeWiki. June 12, 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Dog_Bites_(periocular)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Moran C, Harrington M, Barnett J, Wayman L, Bond J. Horsing Around: A Retrospective Study of Equestrian Related Eye Injuries in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2025;79:446-452. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2025.09.009

- ↑ Khurana RN, Leder HA, Nguyen QD, Do DV. Enterococcus casseliflavus endophthalmitis associated with a horse tail injury. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(11):1551-1552. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.282

- ↑ Ibrahim O, Olusanya B. Occupational cow horn eye injuries in ibadan, Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(6):959-961. doi:10.4103/2141-9248.144926

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Goldblum D, Frueh BE, Koerner F. Eye injuries caused by cow horns. Retina Phila Pa. 1999;19(4):314-317. doi:10.1097/00006982-199907000-00008

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Lécuyer R, Boutoille D, Khatchatourian L, et al. Listeria Endophthalmitis Cured With Linezolid in an Immunocompetent Farmer Woman: Hazard of a Sweep of a Cow’s Tail. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(11):ofz459. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz459

- ↑ Rao P, Ramchandran R, Baldonado K, et al. Patient perspectives on accessing eye-related healthcare from rural communities. Eye Lond Engl. 2024;38(17):3389-3391. doi:10.1038/s41433-024-03266-z

- ↑ Bansal B, Tibrewal S, Rath S, Sharma R, Ganesh S. Double extraocular muscle avulsion following injury by goat’s horn. Strabismus. 2025;33(4):273-277. doi:10.1080/09273972.2025.2454480

- ↑ Ackermans NL, Varghese M, Williams TM, et al. Evidence of traumatic brain injury in headbutting bovids. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2022;144(1):5-26. doi:10.1007/s00401-022-02427-2

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Wykes WN. Rat bite injury to the eyelids in a 3-month-old child. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73(3):202-204. doi:10.1136/bjo.73.3.202

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Bonthius DJ. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: an underrecognized cause of neurologic disease in the fetus, child, and adult. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2012;19(3):89-95. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2012.02.002

- ↑ Wiwatwongwana D, Ausayakun S, Chaidaroon W, Wiwatwongwana A. Bat attack! : an unusual cause of keratouveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(7):1109-1110. doi:10.1007/s00417-011-1739-0

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Abdulla HA, Alkhalifa SK. Ruptured Globe due to a Bird Attack. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2016;7(1):112-114. doi:10.1159/000444180

- ↑ Levitz LM, Carmichael TR, Nissenbaum M. Severe ocular trauma caused by an ostrich. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(4):591. doi:10.1136/bjo.2003.029116

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Al-Sharif EM, Alkharashi AS. An unusual case of penetrating eye injury caused by a bird: A case report with review of the pertinent literature. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2019;33(2):196-199. doi:10.1016/j.sjopt.2018.12.007

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Baskaran P, Ramakrishnan S, Dhoble P, Gubert J. Traumatic endophthalmitis following a crane pecking injury - An unusual mode. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2016;6:Doc01. doi:10.3205/oc000038

- ↑ Lekse Kovach J, Maguluri S, Recchia FM. Subclinical endophthalmitis following a rooster attack. J AAPOS. 2006;10(6):579-580. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.08.007

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 33.9 Sharma VK, Baranwal VK. Snake venom ophthalmia. Med J Armed Forces India. 2015;71(Suppl 1):S197-198. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.01.003

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Duff SM, Bowman A, Blake CR. Coluber Constrictor Bite to the Eye: A Novel Case Report of a Wild Snake Bite to the Eye in North America and Review of Literature. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e12125. doi:10.7759/cureus.12125

- ↑ Chen CC, Yang CM, Hu FR, Lee YC. Penetrating ocular injury caused by venomous snakebite. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):544-546. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.005

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Pejic R, Simic Prskalo M, Simic J. Ocular Hypotonia and Transient Decrease of Vision as a Consequence of Exposure to a Common Toad Poison. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2020;2020:2983947. doi:10.1155/2020/2983947

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Teberik K, Ozer PA, Ozek D, Akkaya ZY. Frog saliva-induced toxic keratopathy: a case report. Int Ophthalmol. 2012;32(6):611-613. doi:10.1007/s10792-012-9606-5

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Ozunal ZG, Karsidag S, Sahin S. Superior Optic Vein Thrombosis Related to Orbital Cellulitis Secondary to Aquatic Injury. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7080. doi:10.7759/cureus.7080

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 Mao C, Hsu CC, Chen KT. Ocular Jellyfish Stings: Report of 2 Cases and Literature Review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27(3):421-424. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2016.05.007

- ↑ Winkel KD, Hawdon GM, Ashby K, Ozanne-Smith J. Eye injury after jellyfish sting in temperate Australia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13(3):203-205. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2002)013%5B0203:eiajsi%5D2.0.co;2

- ↑ Bunya V, Weissbart S, Moshirfar M. Palytoxin Keratitis/Keratoconjunctivitis (Coral Keratitis). EyeWiki. November 1, 2024. https://eyewiki.org/Palytoxin_Keratitis/Keratoconjunctivitis_(Coral_Keratitis)

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Penland RL, Boniuk M, Wilhelmus KR. Vibrio ocular infections on the U.S. Gulf Coast. Cornea. 2000;19(1):26-29. doi:10.1097/00003226-200001000-00006

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Massey EL, Weston BC. Vibrio vulnificus corneal ulcer: rapid resolution of a virulent pathogen. Cornea. 2000;19(1):108-109. doi:10.1097/00003226-200001000-00021

- ↑ Bunya V, Tripathy K, Justin G, et al. Ocular Bee Injuries. EyeWiki. June 6, 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Ocular_Bee_Injuries

- ↑ González-Martín-Moro J, Altares-Mateos V, Padeira Iranzo V, et al. The Multiple Faces of Setae Induced Ocular Inflammation (Ophthalmia Nodosa): A Review. Semin Ophthalmol. Published online May 22, 2025:1-20. doi:10.1080/08820538.2025.2503912

- ↑ Bunya V, Tripathy K, Weissbart S, Kavalaraki M, Gurnani B. Ophthalmia Nodosa. EyeWiki. November 11, 2024. https://eyewiki.org/Ophthalmia_Nodosa

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Sadhasivamohan A, Palaniappan V, Karthikeyan K. Nairobi eye - “Wake and see” disease. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2022;15(3):417-418. doi:10.4103/ojo.ojo_145_21

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 48.7 48.8 48.9 Verma S, Gupta S. Ocular manifestations due to econda (Paederus sabaeus). Med J Armed Forces India. 2012;68(3):245-248. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2011.11.006

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Villada JR, Panos MI, Del Cerro I, Granados JM. Ocular Injury Caused by the Bombardier Beetle. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2021;12(2):629-633. doi:10.1159/000517740

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Uzun A, Gök M, İşcanlı MD. Tick Infestation of Eyelid: Two Case Reports. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2016;46(5):248-250. doi:10.4274/tjo.43660

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 51.5 Hudson BJ, Parsons GA. Giant millipede “burns” and the eye. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91(2):183-185. doi:10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90217-0

- ↑ Kim L, Tripathy K, Sandhu R, Bhagat N, Lim J, Patel N. Ophthalmomyiasis. EyeWiki. June 23, 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Ophthalmomyiasis

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 Aik Kah T. Ocular Injury Caused by the Asian Weaver Ant. Cureus. 2025;17(9):e92569. doi:10.7759/cureus.92569

Footnotes

* Copyright © 2025, Hasegawa et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

† Copyright © 2016 by S. Karger AG, Basel. This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-4.0 International License (CC BY-NC). Usage and distribution for commercial purposes requires written permission. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

‡ Copyright © 2016 Baskaran et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

§ Copyright © 2020, Duff et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

¶ Copyright © 2020, Ozunal et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

# ©Turkish Journal of Ophthalmology, Published by Galenos Publishing. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice

|| Copyright © 2025, Aik Kah et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0., which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice