Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology

Definition

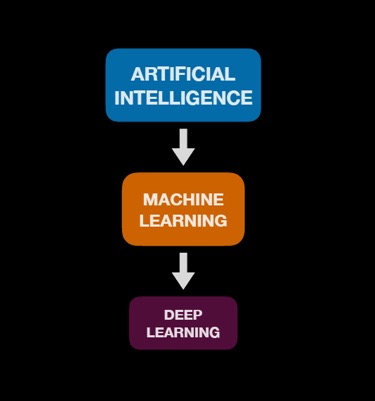

Artificial Intelligence (AI), a term introduced in the 1950s, refers to software that can mimic cognitive functions such as learning and problem solving.[1] It makes it possible for machines to learn from experience and adjust to new inputs. AI machines can be trained to accomplish such tasks by processing and recognizing patterns in large amounts of data.[1] It has numerous applications in several fields of ophthalmology.[2]

Types of Artificial Intelligence

Simple Automated Detectors

A simple automated detector is a system that is fed an algorithm that identifies the presence or absence of features (e.g. location, dimensions, or contour of a lesion) based on objective criteria. The input into the system is a set of step-wise rules generated by the individuals who are engineering a model that predicts outcomes.[3] This rule-based algorithm assesses features and ultimately yields an outcome (e.g. diagnosis) based on the patterns identified.[3]The rules are generally written by programmers or content experts using input features that they have previously identified as being important.

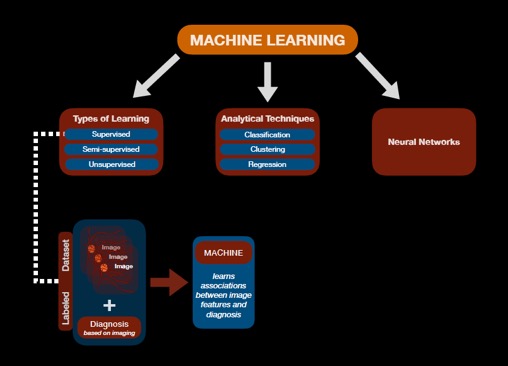

Machine Learning

A more advanced form of AI is machine learning. Unlike simple automated detectors, the input into machine learning is a training dataset (e.g. a set of images) rather than predefined algorithms (i.e. rules written by the program designers).[4] Machine learning can be further classified into supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised learning.[4] In unsupervised learning, the machine must “learn” on its own the different labels or classes of inputs based on the dataset presented. The machine learning process can be assisted by providing the machine with objective guidance through a labeled dataset and is the basis for supervised learning.[4] A labeled dataset, for example, is a collection of images that have been preassigned a “ground truth” diagnosis by experts who utilized standard diagnostic methods. A consensus amongst experts on a reference standard diagnosis for each item (e.g. image) in the set may strengthen the quality of the dataset that is presented to the machine during the initial learning phase when the algorithms are built.[5] Presenting an machine learning system with a hybrid of both training and labeled datasets is termed semi-supervised learning.[4] See Figure 1.

Machine Learning Techniques

Machine learning models can employ various techniques to predict an output. Classification is one technique that is built upon supervised and semi-supervised learning.[4] This type of system allows for concrete categorization of outputs (e.g. presence versus absence of disease; mild versus severe category of disease).[4] When classes or labels for the training data are not provided, unsupervised machine learning is still able to cluster similar inputs, even if it is not able to definitively classify the individual clusters.[4] When ordinal or continuous outcomes are desired rather than a simple classification, regression techniques can employ supervised learning to determine a continuous score (e.g. numerical value) based on an input (e.g. image).[4]

The architecture of machine learning models can employ neural networks (to be discussed next) in addition to other techniques such as genetic programming, support vector machines, statistical regression, tree-based classification & regression, or random forests.

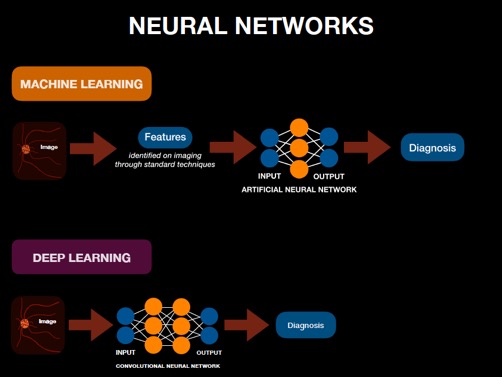

Utilizing Neural Networks in Machine Learning

An AI system designed using artificial neural networks (ANNs) is considered a subset of machine learning and can be used in both supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised learning. The architecture of an ANN is composed of layers of neurons. An ANN consists of an input layer that is introduced with (e.g. diagnostic) features determined by programmers and subject matter experts in advance, intermediate neural network layers, and a final output layer that receives the analysis from the intermediate layer and determines the outcome (e.g. diagnosis).[3][4] A layer refers to the level at which analysis of one set of distinct (e.g. diagnostic) features are conducted. Each layer is composed of multiple neurons, or nodes, that perform the higher level analytical processing, initially described as emulating the neuronal functions of the brain.

Each node can be considered a basic calculation of the multiple inputs including multiplication of an individual input by an assigned “weight”, addition of a bias, and a (non-linear) mathematical activation function which enables more complex analysis. The result of a each node in one layer is then transmitted to multiple nodes in the next layer where further computations occur. At the output layer in the neural network, the resulting number approximates a continuous measurement (i.e. a regression prediction) or the probability of an outcome or classification. Each item (e.g. image) in the dataset is usually analyzed multiple times during training using back-propagation to update the network's weights and biases to maximize the performance of the model's predictions. See Figure 2 for visualization of this process (and comparison to Deep Learning described below).

Deep Learning

In a simple neural network, there are only a few layers: as few as just an input and output layer. However, deep learning algorithms are neural networks with an expanded number of communicating layers between the input and output layers: from dozens to hundreds. This intricate type of machine learning involves supervised learning with labeled datasets (e.g. images with preassigned expert diagnoses). See Figure 3 for a flow diagram of this relationship.

One popular form of deep learning neural network is the convolutional neural network (CNN). Other deep learning models include recurrent neural networks, Long Short Term Memories (LSTMs), and fully-connected deep neural networks.

The CNN begins with a large matrix of inputs into the first layer (often a 2D image), which then results in an output that serves as the input for the next layer in the series. The connections between layers describe a convolution propagating local information (where the weights and biases of the convolution are shared between all nodes of a layer to dramatically reduce the parameter space of the model and thus the complexity of training the model). The analysis from each layer is transmitted throughout the network until the final layer produces the outcome.[4] CNNs designed for image-based diagnosis, for example, analyze the pixels in correlation with the features seen in the disease state depicted.[3] If the predicted outcome does not match the expert outcome determined using standard methods, then errors in the prediction are propagated backwards through the CNN to adjust the weights to reduce the error. After training, the model is presented with a training dataset (e.g. unlabeled images) and produces an outcome (e.g. diagnosis) based on what the machine “learned” under supervision. See Figure 2 for visualization of this process in comparison to Machine Learning as described above.

While the training dataset can provide an initial analysis, it is important to ensure that the algorithm is generalizable to new datasets. This is accomplished with appropriate control during training and verified using validation datasets, which minimize “overfitting” the algorithm to the training dataset. Techniques to minimize overfitting include dataset expansion, augmentation, applying drop out, and regularization. Augmentation can be utilized in examples where the original dataset cannot be expanded. For example, images can be altered (resizing, cropping, rotating, etc) in such a way that they still represent realistic examples. Drop out can be used to train the algorithm by ignoring a certain subset of nodes, training other nodes to perform the work of others. Regularization involves altering the total of all weights in the system. The final step is to evaluate the model’s performance on a new dataset that it has not been exposed to.[4]

Limitations of Artificial Intelligence

As a quickly evolving field, AI comes with some challenges. For one, the accuracy of outcomes is heavily dependent on the quality of inputs.[6] This has been described as the “garbage in, garbage out” phenomenon; if the initial dataset presented to the machine is inadequate, then the predictions generated by the AI tool will be inaccurate. In some situations, output recommendations by AI tools may be simply incorrect. For example, IBM Watson Health’s AI algorithm, which predicts treatments for patients with cancer, recommended the use of bevacizumab in patients with severe bleeding.[6] However, hemorrhage is stated as a black box warning for bevacizumab. This example highlights the importance of training and validating AI algorithms.[5]

Erroneous predictions by AI algorithms can bring up the issue of liability for physicians. Current law protects physicians from liability, as long as they follow the standard of care.[7] Thus, physicians are incentivized to use AI predictions only if they confirm existing decision-making processes, instead of as a resource to improve and build upon patient care.[8] In the future, further medicolegal implications must be considered if AI becomes integrated into the standard of care.

Additionally, NN algorithms are not entirely designed by programmers, but by rules inferred from the training dataset. They arrive to conclusions opaquely as programmers are unaware of the reasoning behind these self-generated rules. This is called the black box dilemma, as people may be hesitant to trust predictions that stem from a process that, by definition, lacks transparency.[9] Additionally, biases and stereotypes inherent in the training dataset become integrated into the model's performance.[10]

There is a fear that AI reduces the need for physicians, as numerous studies have shown that certain algorithms have higher success rates of diagnosing diseases as compared to those of clinicians.[11][12] This has been a concern in image-based fields such as radiology and pathology, with concerns that it may limit physicians by narrowing the scope of their clinical judgment, reducing a reliance on broad differential diagnoses, and automating the process of patient care which may affect that patient-physician relationship. By predicting diagnoses in a purely algorithmic and objective manner, AI dismisses any subjective facets of a disease that may be unique to a patient, potentially overlooking crucial information.[13]

However, it can be argued that AI merely augments the work of physicians by serving as a diagnostic tool generating predictions that can positively affect patient management.[3] For example, an AI-integrated telemedicine platform designed to screen and refer patients with cataracts exhibited diagnostic performance of over 90%. More importantly, the platform improved physician efficiency by allowing them to evaluate ten times as many patients a year.[14] By complementing the role of physicians, AI has the potential to significantly improve patient care by increasing efficiency and outcomes as it becomes incorporated into clinical practice in the near future.

Method to Approaching Artificial Intelligence Studies

Al is rapidly involving in the field of ophthalmology and new experimental algorithms are emerging in the literature that describe the AI system and methodology. Articles regarding AI studies can be challenging to understand, especially when there is no standardized way of presenting data, statistics and clinical value. Nevertheless, there are fundamental characteristics that readers can look for in order to critically appraise such studies. In the introduction, articles will typically emphasize the clinical gap that AI may fulfill and the research question it seeks to answer. Additionally, the introduction usually summarizes a thorough literature search that explores existing technologies pertaining to the disease and discusses the potential for AI to build on these technologies to provide further insight.[5]

In the methods section, articles will elaborate on the basic framework of an AI system, which consists of two phases: (1) training and validation and (2) testing. The training and validation phase can be further broken down into two other parts: (1) selection of a machine learning model; and (2) a training dataset entailing data and/or images.[5] Datasets may vary in sample size and may be limited in diversity or generalizability. As mentioned previously, the ease with which machine learning models can enshrine biases implicit in the data and the opaqueness of the reasoning behind their conclusions makes the selection of training data of fundamental importance. An article's method section should describe the source of the training data sets and the data's characteristics (diversity, gender, disease severity range, ages, etc.). All training steps should be described including the machine learning model upon which the study is based (including the source of any pre-trained weights if only transfer learning is performed), the versions of software used, and where source code for the model training can be obtained.

Moreover, AI studies should clearly describe the workflow for use of the AI system. For example, the workflow may consist of an input, such as an image, which is then analyzed by the AI system to detect specific features and ultimately produce an outcome, a diagnosis. The resulting diagnosis may complement the work of physicians, demonstrating the potential for reported AI systems to be ultimately incorporated into clinical practice.

As described by Ting et al., AI articles should generally include limitations of the AI systems discussed. This gives readers a clearer understanding of the potential for integration of AI into clinical practice and of the associated shortcomings of such systems.[5]

Potential Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology[2]

The incorporation of AI systems into clinical practice can potentially enhance productivity in the workplace, as well as aid in the clinical decision-making or patient communication processes.[15] [16]Applying AI to medical diagnostic assessments allows for the automatic analysis of imaging, for example, and the subsequent generation of a diagnosis or prediction of a disease course.[3][15] In ophthalmology, many AI platforms are being explored for potential use in the detection, surveillance, and treatment of various ocular diseases. However, many are in the experimental phase and further evaluation must be done to assess if these algorithms are appropriate for clinical practice.[17] AI algorithms have been described in the literature in several fields in ophthalmology such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, retinopathy of prematurity, retinal vascular occlusions, keratoconus, cataract, refractive errors, retinal detachment, squint, and ocular cancers. It is also useful for intraocular lens power calculation, planning squint surgeries, and planning intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections. In addition, AI can detect cognitive impairment, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, stroke risk, and so on from fundus photographs and optical coherence tomography.[2]

Glaucoma

Intraocular Pressure (IOP)

Prediction of IOP trends from previous data and medications would be a useful and plausible use of AI. As of now, AI was used for evaluation of data from Sensimed Triggerfish (Sensimed AG, Lausanne, Switzerland), which is a contact lens based continuous IOP monitoring device which actually measures only the corneal strain changes due to IOP fluctuations. Martin et al used data from 24 prospective studies of Triggerfish using random forests (a machine learning method) to identify the parameters associated with glaucoma patients.[18]

Optic Disc Photography

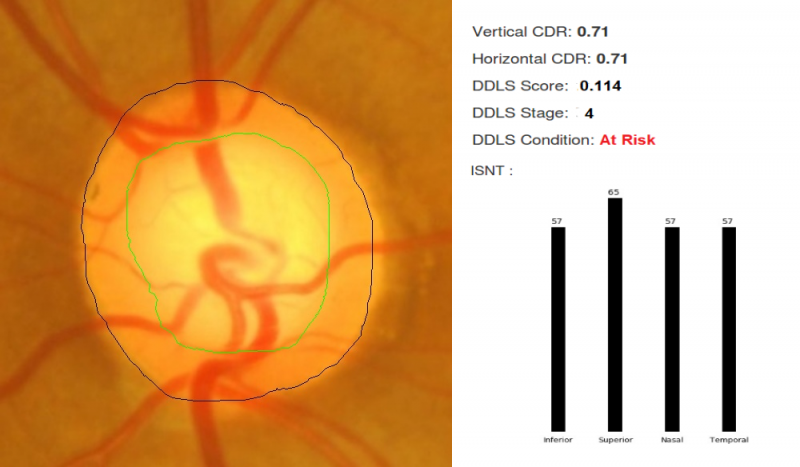

For fundus photographs, Li et al evaluated a deep learning algorithm that showed a high sensitivity (95.6%) and specificity (92%) to detect referable glaucomatous optic neuropathy.[19]The disadvantage was that high myopia caused false negatives and physiological cupping caused false positives. Al-Aswad et al evaluated Pegasus (Visulytix Ltd., London UK), a deep learning system to detect glaucomatous optic neuropathy from color fundus photographs and showed that it outperformed 5 out of 6 ophthalmologists in the study.[20] Pegasus is the AI system that is available free for use in the Orbis Cybersight Consult Platform. NetraAI (Leben Care Technologies Pte Ltd) is another AI that evaluates glaucomatous fundus photographs. Cerentini et al used the GoogLeNet deep learning network[21] to develop an automatic classification method to detect glaucoma in fundus images. Haleem et al used a novel technique for automatic boundary detection of optic disc and cup to aid automatic glaucoma diagnosis from fundus photos.[22] Thompson and team was able to use deep learning to measure NRR loss from optic disc photos.[23] Indian startup Kalpah Innovations (Vishakapatnam, India) released Retinal Image Analysis – Glaucoma (RIA-G),[24] cloud based software in 2016 to analyse fundus images to look for the likelihood of glaucoma. It uses advanced image processing algorithms to measure disc size, cup size, C/D ratio, neuroretinal rim thickness, disc damage likelihood score (DDLS), and to look for violation of ISNT rule. It also uses deep learning to learn from the user in case of errors in automated detection.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) - RNFL, GCL

OCT machines automatically measure disc size, cupping, neuroretinal rim area, RNFL thickness, and GCL thickness. All of these parameters can be estimated using AI-based image segmentation techniques.[25] Omodoka et al, using a neural network classified images from swept-source OCT into Nicolela's 4 optic disc types with high accuracy.[26] Muhammad et al showed that a hybrid deep learning method on a single wide field swept-source OCT had 93.1% sensitivity in detecting glaucoma suspects.[27] Asaoka et al evaluated a deep learning algorithm that diagnosed glaucoma based on macular OCT for RNFL and GCL.[28] Other studies by Christopher et al,[29] Barella et al,[30] Bizios et al,[31] & Larossa et al[32] evaluated unsupervised machine learning, machine learning classifiers, artificial neural networks, support vector machines, and segmentation methods for glaucoma OCT.

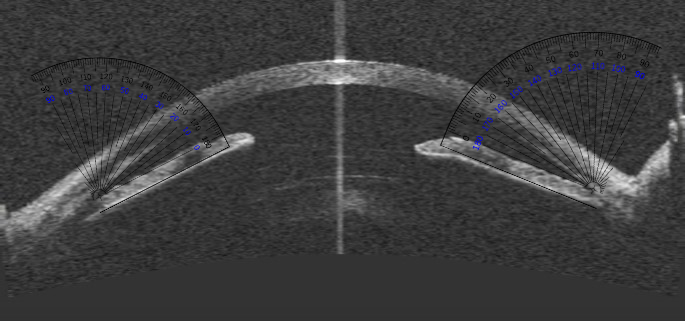

Anterior Segment OCT (AS-OCT)

AS-OCT images can also be processed for structure segmentation, measurement, and screening for angle closure using algorithms being developed.[33] Niwas et al evaluated a fully automated model to classify angle closure glaucoma from AS-OCT scans and showed an accuracy of 89.2%.[34]

Visual Fields (VF)

AI can potentially help in rapid and accurate interpretation of visual fields. Asaoka et al used a feed-forward neural network to identify pre-perimetric visual fields which did not meet Anderson-Patella's criteria.[35] Li et al evaluated a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to automatically differentiate glaucomatous VFs from non-glaucomatous VFs.[36] Goldbaum et al used unsupervised machine learning and variational Bayesian independent component analysis mixture model (vB-ICA-mm) to analyze VF defects.[37] Andersson, Heijl, and colleagues showed that a trained artificial neural network obtained 93% sensitivity and 91% specificity in evaluating glaucoma VF and performed at least as well as clinicians.[38] Bowd, Weinreb, and colleagues successfully used variational Bayesian independent component analysis-mixture model (VIM), an unsupervised machine-learning classifier to analyze frequency doubling technology (FDT) perimetry data.[39]

Combined Approaches

Oh et al used an artificial neural network (ANN) to predict OAG with an accuracy of 84.0%, sensitivity of 78.3%, and specificity of 85.9%.[40] Their ANN evaluated four non-ophthalmic factors (sex, age, menopause, and duration of hypertension) and five ophthalmic factors (IOP, spherical equivalent refractive errors, vertical cup-to-disc ratio, presence of superotemporal RNFL defect, and presence of inferotemporal RNFL defect). They suggest that visual fields, being cumbersome and impractical for screening, can be avoided with this approach.

Predicting the Prognosis

For visual field progression analysis, Goldbaum et al used Progression of Patterns (POP), a machine learning classifier algorithm.[41] Yousefi et al showed that machine learning detects VF progression consistently, without confirmation visits and even slow progression.[42] All these methods can ideally run on portable perimetry devices like the smartphone based virtual reality perimetry such as PeriScreener, VirtualEye, and C3FA.[43] Wen, Lee and colleagues trained a deep learning system with 32,443 visual fields (24-2 VFs) taken between 1998 to 2018 and the resulting CascadeNet-5 model was able to predict future visual fields for up to 5.5 years based on a single input visual field.[44] Kazemian et al developed and validated Kalman Filters which could predict personalized trajectory of progression of Mean Deviation of Visual Fields at different target IOPs.[45] This would be a helpful guide for customized target IOP.

Ocular Oncology

Emulating a decision tree model, a machine learning algorithm was developed to anticipate the course of periocular reconstruction during surgical treatment of basal cell carcinoma.[46]Moreover, several machine learning systems, through the use of artificial neural networks, have been designed to predict disease outcomes for choroidal melanoma by analyzing demographic data and oncologic history.[1]Habibalahi et al. implemented machine learning techniques in the development of a multispectral imaging system for the detection of ocular surface squamous neoplasia on biopsy[47]. The system demarcates the region of neoplastic changes, providing a visual representation of disease margins to the clinician or surgeon in minimal time.[47]

Cataracts

Machine learning programs have been developed to detect and grade cataracts. [46][48] [49] Wu et al validated a model using an AI algorithm called ResNet to identify referable cataracts.[50] Deep learning algorithms for the assessment of congenital cataracts in particular have also been reported.[1][51] A validated system by Liu et al, known as the CC-Cruiser, demonstrated high accuracy for identifying the region, density, and degree of congenital cataract formation based on slit-lamp photographs.[51]Machine learning systems for cataracts have also been shown to adequately guide plans for surgical intervention, as well as anticipate the likelihood of posterior capsular opacification developing post-operatively.[1][46][52]Calculating intraocular lens power can be conducted through machine learning methods.[46] One notable example is the Hill-RBF formula that analyzes the following inputted data: axial length, central corneal thickness, anterior chamber depth, lens thickness, corneal diameter, and keratometry measurements.[46]

Pediatric Ophthalmology

In the pediatric population, timely ocular management is critical for the preservation of vision. Incorporation of AI into screening and treatment practices may aid in achieving optimal ophthalmic care A deep learning algorithm for the assessment of strabismus from external images has been developed with the potential for implementation in tele-ophthalmology. Other systems to detect strabismus are based on eye tracking deviations or retinal birefringence scanning. [53] [54] Other machine learning systems have the potential to facilitate screening for high myopia among other refractive errors, as well as classify children susceptible to reading disabilities.[55]Van Eenwyk et al describes a system using machine learning that incorporates the Brückner pupil red reflex imaging and eccentric photorefraction to detect amblyogenic features of strabismus or high refractive errors.[56] AI systems for congenital cataracts are discussed above in the Cataract section.

Retina

Diabetic Retinopathy

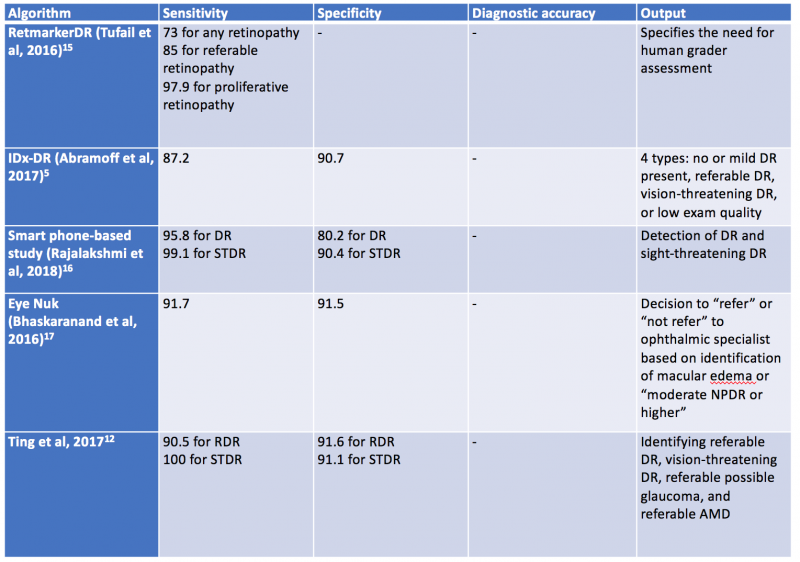

Validated AI systems for the assessment of DR have been reported to perform diagnostic functions with high sensitivity and specificity. [57] [58] [59]In particular, AI algorithms have been shown to be effective in detecting clinically significant macular edema as well as advanced stages of DR.[60] Prior to the deep learning era, AI models have been trained based on “feature-based” learning to detect microaneurysms, hemorrhages, hard or soft exudates and vessel maps. RetmarkerDR is another system that has been used for DR screening, by screening out images without DR and sorting images that have DR into a group that requires further human grader assessment.[61] A notable characteristic of RetmarkerDR is that it can track disease progression by comparing current images to those that were initially screened out, potentially providing insight on progression of DR.[62]

In 2016, Abramoff et al reported a comparison of a deep-learning enhanced algorithm for the automated detection of DR to an identical algorithm that did not utilize deep learning and noted improved specificity for referable DR. This algorithm utilizes a previously reported reference consensus standard for referable DR, the International Clinical Classification of Diabetic Retinopathy, and provides four outputs: negative (none or mild DR), referable DR, vision threatening DR, and/or low exam quality which noted a limitation in analysis or image quality.[57] Google also validated a DR detection algorithm which assigns an image a number between 0-1 that correlates with the likelihood of DR in the image.[59] Studies have shown the sensitivity and specificity of this algorithm are above 90%.[63] Ting et al described and validated a deep learning system that not only identifies vision threatening and referable DR, but also AMD and possible glaucoma in a multiethnic cohort.[64]

In 2018, Abràmoff and colleagues obtained the first US Food and Drug Administration approval of their AI system IDx-DR system using deep learning, after a pivotal prospective clinical trial of 900 patients. All images were obtained using the Topcon Fundus camera (Topcon Medical). This deep learning platform functions by independently assessing the quality of the images inputted into the system and indicates whether there is “more than mild” DR present on imaging.[1][65]Table 1 highlights a select group of AI algorithms for DR screening, given that there are many that have been described in the recent years.[66] [67] [68]

In 2020, the EyeArt system by Eyenuk became another autonomous AI system that is FDA approved for the detection of mtmDR. [69] This system utilizes two 45-degrees fundus photos per eye and the cloud based software results in a report for the presence or absence of mtmDR or vision threatening DR (vtDR) within 60 seconds. A multicenter clinical trial comparing the AI system to a reading center grading of widefield images from the same eyes showed high sensitivity and specificity: sensitivity was 95.5% and specificity was 85% for detection of mtmDR; sensitivity was 95.1% and specificity was 89% for detection of vtDR without dilation. Imageability was high without dilation. A recent study has shown the EyeArt system has significantly higher sensitivity than general ophthalmologists or retina specialists for detection of mtmDR. [70]

AI programs have also utilized fundus photography via smartphones. For example, EyeNuk is an AI screening program that utilizes the EyeArt software which has shown positive results with over 95% sensitivity when using fundus images obtained from smartphones. EyeArt also utilizes standard desktop fundus cameras.[5] As AI-enhanced screening tools become more widely utilized, it is also important to integrate screening for other diseases. In 2023, the AEYE-DS system was FDA approved for DR screening and in 2024, a handheld version of AEYE-DS was FDA approved.

Retinopathy of Prematurity

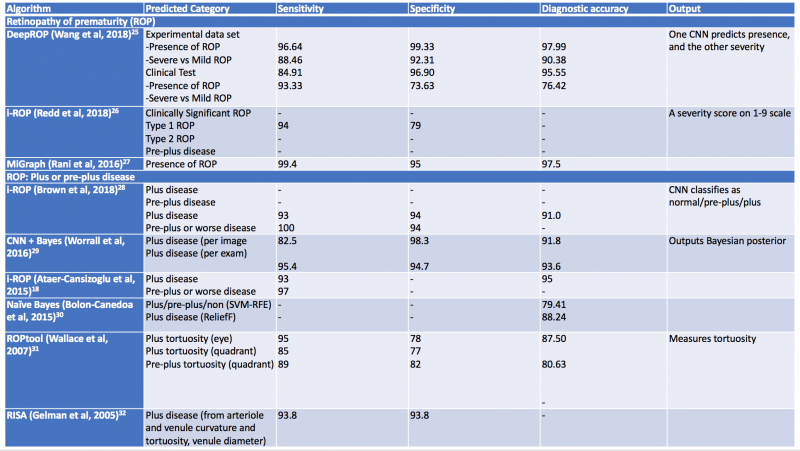

Challenges in retinopathy of prematurity screening and diagnosis include diagnostic variability, paucity of specialists in ROP, and access to care issues. Machine learning systems have been developed as a possible solution to address these challenges.[71] These systems evaluate vascular changes, features of the disease such as zone or stage, category of disease, and disease progression. Recent advancements in AI have allowed for the development of quantitative scores for defining features of disease, such as rating the degree of plus disease or identifying the number of regions with neovascularization. [72] [73]One such example is the i-ROP score, developed by the Imaging and Informatics in Retinopathy of Prematurity (i-ROP) Research Consortium. This was shown to be non-inferior to human expert diagnosis, notably when identifying vascular changes such as pre-plus and plus disease.[74]

Additional computerized algorithms using automated methods for detection of plus disease have been previously reported, including ROPtool, Retinal Image multiScale Analysis (RISA), VesselMap, and Computer-Assisted Image Analysis of the Retina (CAIAR).[75] [76] [77]The hallmark features of plus disease in ROP are defined based on the degree of arteriolar tortuosity and venular dilation. Both the ROPtool and the RISA systems perform exact measurements of vessel curvature relative to vessel length, and the ROPtool and the VesselMap define the location of vascular changes in relation to the optic disc. The VesselMap, unlike the former two computing modalities, measures the dimensions of the vasculature by evaluating the intensity of light seen in planes orthogonal to the long axis of vessels. [75] [76] [77] The CAIAR system quantifies the extent of arteriolar tortuosity and venule width. Over time, these AI systems have been updated and expanded, and some have shown promising results with their demonstration of high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of different aspects of plus disease. Table 2 summarizes systems designed for automated detection of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity.[78] [79] [80] [81] [82] [83] [84] [85]

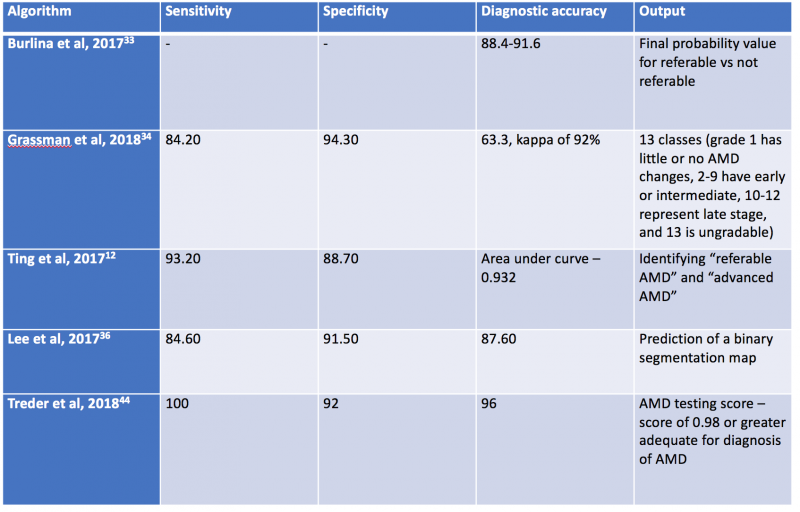

AI algorithms have been applied to both fundus photographs and optical coherence tomography (OCT) to detect age-related macular degeneration. Using deep learning, AI was shown to achieve comparable diagnostic performance in detecting referable AMD when compared to human graders.[86] [87] [88] In Burlina et al, the AI system was developed using AlexNet and more than 100,000 Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) stereoscopic fundus photos and demonstrated that the 4-step grading was comparable to that of a human grader. The AI system was further developed to estimate the 5-year risk of progression to advanced AMD. Subsequently, Grassman et al demonstrated that multiple convolutional neural networks can be trained on the same dataset and were able to outperform human graders.[85]

Using retina OCT images, AI systems can be trained to perform segmentation, classification and prediction. In segmentation, many AI systems were shown to display highly accuracy in segmenting different retinal layers on OCT, and this is important to quantify intraretinal fluid, subretinal fluid and pigment epithelial detachment.[61][89] When compared to non-computerized segmentation techniques, the deep learning algorithm developed by Lee et al properly differentiated fluid accumulation from other abnormal retinal findings, which was also demonstrated by the validated ReLayNet deep learning system.[90] Volumetric analysis of intraretinal fluid and drusen have also been evaluated using deep learning methods. [3][91] [92] For classification tasks, Kermany et al showed the value of using transfer learning in detecting three retinal conditions, namely drusen, neovascular AMD and diabetic macular edema.[93]Following this study, De Fauw et al further confirmed not only the ability of deep learning in detecting >50 retinal conditions, but also the robustness of the AI system to help triage the urgency of referrals for patients with retinal diseases.[94] Lastly, for the prediction tasks, using HARBOR data, Bogunovic et al and Erfurth-Schmidth demonstrated the ability of AI system to predict the long term visual outcome (at month 12) by integrating the OCT images segmented using deep learning, and utilized the machine learning approach with other clinical data for analysis.[95] [96] [97] Table 3 summarizes current AI algorithms utilized in AMD.

FDA Approval of AI Algorithms

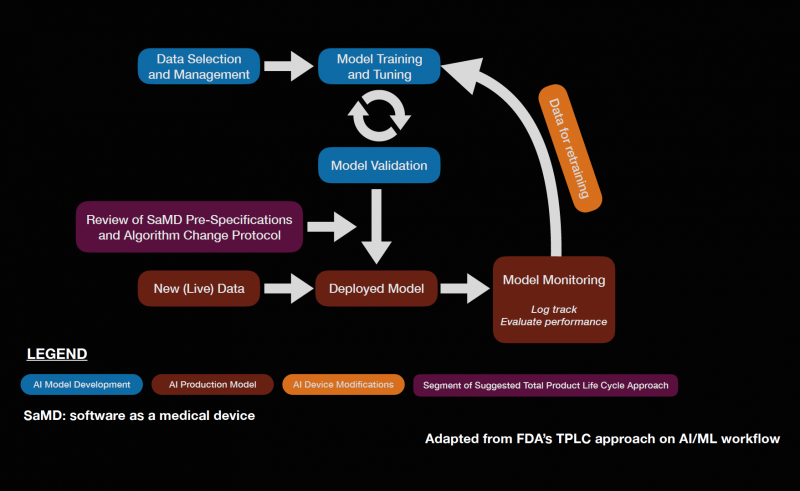

Software as a medical device (SaMD) is an area of rapidly expanding research and development. The FDA approval of IDx-DR in 2018 sparked complex discussions regarding future approval of independent AI algorithms. Subsequently, the FDA published a statement in April of 2019 proposing a novel regulatory framework for AI based medical devices. The guidelines for medical devices prior to this statement did not take into account the dynamic nature of machine learning algorithms. Previously, medical devices reviewed by the FDA were primarily static in nature and were evaluated by comparing them to similar products already on the market.[98] It is also important to assess the quality of the training and validation datasets to ensure that the results are generalizable across diverse patient populations. The figure below describes a potential workflow for the FDA approval of AI systems.

The dynamic nature of AI systems makes it difficult to predict at what point the algorithms should be reviewed. While the initial training and validation datasets may yield promising results, it is possible that variations in output can occur as more data is processed by the system when it is available on the market. To address this issue, the FDA is implementing a system called pre-certification, which focuses on how the product and AI system is developed. The FDA also described categories of software modifications that may require a premarket submission, especially when considering changes that may introduce a new risk, prevent harm, or changes that significantly affect the clinical functionality of the software. The International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) created a risk-based approach to categorize SaMD, ranging from I to IV, which reflects the risk associated with the clinical situation and device use. The FDA also described a “total product lifecycle regulatory approach” with regards to SaMD given that these products can adapt and improve with real-world use. This would enable the evaluation and monitoring of the software product from its premarket development to post-market performance. Regulatory guidelines specifically for AI is a step in the right direction as it allows AI based medical devices to evolve in ways to improve itself while also meeting the FDA’s standards for safety and efficacy. The Collaborative Communities in Ocular Imaging (CCOI) AMD group is working to create standards for AI algorithms to be compared to as a first step towards an AMD screening system.[99]

Oculoplastics

In oculoplastics, AI has the potential to aid in automated processing and measurement of patients’ facial dimensions to aid in pre- and post-op evaluations, as well as clinical decision support for oculoplastic referral by non-ophthalmologists. Semantic segmentation networks have been trained to automate periorbital measurements with comparable performance to human graders[100]. Hung et al. applied similar technology to training a model to aid general practitioners in decision making regarding referral of patients with blepharoptosis, which was shown to outperform the sensitivity and specificity of referral decisions made by non-ophthalmic physicians.[100] Simsek et al. developed an AI algorithm to objectively assess patients’ progress post-eyelid surgery in a standardized and repeatable manner [101].

Neuro-Ophthalmology

In neuro-ophthalmology, the laterality of a pathological process is important in narrowing down differential diagnoses. For example, bilateral optic disc edema and unilateral optic disc edema are typically caused by different disease states. Therefore, the ability of AI to distinguish laterality between the right and left eye is important for beginning the task of making a diagnosis.[102] Liu et al developed a DLS that achieved 98.78% accuracy in this respect, rivaling the much larger data set of Jang et al.[102][103] This makes the interesting conclusion that DLS can be accurate even with small data sets.

In a landmark retrospective study in 2020 utilizing 14,341 ocular fundus photographs, Milea et al found that deep-learning systems using retinal cameras were able to differentiate normal optic discs from those with papilledema or other non-papilledema abnormalities.[104] After being cross-referenced with four expert neuro-ophthalmologists, it was determined that the DLS had sensitivity of 96.4% and a specificity of 84.7% for detecting papilledema. A variety of retinal cameras were used in this study, including Topcon ©, Zeiss ©, and Cannon ©. This DLS was further tested against two expert neuro-ophthalmologists after evaluating 800 new fundus photographs. Classification was split into normal optic discs, papilledema, or other optic disc abnormalities. In this study, the DLS classified 678 of 800 (84.7%) photographs correctly, while expert 1 correctly classified 675 of 800 (84.4%) and expert 2 classified 641 of 800 (80.1%).[105] These studies highlight the possibility of faster and more accurate recognition of papilledema so treatment can be initiated right away.

AION and NAION are two vision-threatening conditions where quick diagnosis and intervention is vital. Levin et al demonstrated in their retrospective study that their neural network could detect AION 94.7% of the time compared to clinicians, with the capability of distinguishing AION from optic neuritis in the presence of overlapping features.[106] However, a careful literature review shows minimal additional research regarding AI and AION detection, lending itself to potential future direction. Similarly, studies covering AI and NAION recognition are also limited. A 2006 study from Feldon et al described the ability of a computerized classification system to characterize NAION severity based on Humphrey Visual Field testing. However, the study lacked clinical applicability and was meant primarily for research purposes.[107]

Additional research into deep learning systems in relation to HVFs has been conducted, albeit regarding glaucomatous changes. Utilizing 32,443 HVFs, Wen et al demonstrated their algorithm was able to create visual field predictions of glaucoma progression using a single initial HVF. The accuracy of the DLS ranged from 0.5 to 5 years, giving clinicians the predictive tools necessary to create more accurate treatment plans.[108]

Glaucoma as a disease is often in the cross-section between glaucoma, the specialty, and neuro-ophthalmology. Because of this, it is important to differentiate glaucomatous optic neuropathy from non-glaucomatous optic neuropathy (NGON), such as AION or NAION, as it may determine which specialist sees the patient. Yang et al applied the convolution neural network of ResNet-50, a MATLAB® DLS, to 3815 color fundus images, displaying 93.4% sensitivity and 81.8% specificity in distinguishing NGON from GON.[109] This has potential to provide clear demarcation between the two pathologies to guide referral, allowing for better use of resources and time.

AI has proven to be essential for enabling a further understanding of Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome (SANS). By incorporating Transfer Learning and Generative adversarial Networks (GAN), we can overcome the challenges posed by the space environment and zero gravity and has enabled us to further understand the pathopysiology of this neuro-ophthalmic condition.[110] [111] [112]

Ethical Considerations of Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology

The use of AI in ophthalmology raises a number of ethical concerns that need to be carefully considered to ensure that it is used for the benefit of all. As AI continues to advance in ophthalmology, a thoughtful and ethical approach is indispensable. Balancing the promise of improved diagnostics and treatment with the responsibility to address ethical concerns is paramount.[113] Establishing and adhering to ethical guidelines ensures that AI in ophthalmology contributes positively to patient care while upholding the highest standards of ethical conduct.[114]

Data Privacy and Security

AI systems rely extensively on vast datasets, often comprising sensitive patient information such as medical histories, diagnostic images, and treatment records. Ensuring the ethical collection, storage, and utilization of this data are fundamental to safeguarding patient privacy and confidentiality.[115] Ethical frameworks must be established to govern the entire data lifecycle, from acquisition to disposal, with strict adherence to privacy regulations and standards.[116] Robust data governance protocols, including encryption, access controls, and anonymization techniques, should be implemented to mitigate the risks of unauthorized access, data breaches, and potential misuse of sensitive health information.[116] Moreover, healthcare institutions must prioritize continuous monitoring, auditing, and compliance verification to uphold the highest standards of data privacy and security in AI-driven ophthalmic practices.[117]

The ethical imperative of data privacy and security in AI implementation extends beyond mere regulatory compliance; it reflects a commitment to patient trust, autonomy, and well-being. Transparency regarding data practices and policies is essential to foster patient confidence and engagement in AI-enabled healthcare.[115] Clinicians and researchers must prioritize patient education and informed consent regarding the collection, storage, and utilization of their health data for AI applications.[118] By upholding ethical principles of transparency, accountability, and patient-centered care, healthcare stakeholders can ensure that the integration of AI in ophthalmology respects and protects patient privacy rights while harnessing the potential of data-driven innovations to improve clinical outcomes and quality of care.

Algorithmic Bias

Algorithmic bias presents a significant ethical challenge in the development and deployment of AI algorithms in ophthalmology. When trained on biased datasets, AI algorithms have the potential to perpetuate and exacerbate existing disparities, particularly concerning patient outcomes and access to care.[119] The ethical implications of algorithmic bias extend beyond individual patients to encompass broader societal implications, including the reinforcement of systemic inequalities. To address these concerns, ethical deployment of AI requires vigilant efforts to detect, mitigate, and prevent algorithmic bias throughout the algorithm development lifecycle.[120] This involves comprehensive data screening processes to identify and mitigate biases inherent in training datasets, as well as ongoing monitoring and evaluation of algorithm performance across diverse patient populations.[121]

Furthermore, ethical AI development mandates the integration of fairness, equity, and diversity considerations into algorithm design and validation processes. Collaborative efforts between clinicians, data scientists, and ethicists are essential to develop AI algorithms that are sensitive to the diverse needs and characteristics of patient populations.[118] Strategies such as algorithmic transparency, interpretability, and explainability can enhance accountability and trust in AI-driven decision-making processes, allowing clinicians and patients to better understand and evaluate the rationale behind algorithmic recommendations.[119] By prioritizing ethical principles of fairness and inclusivity, stakeholders can mitigate the risks of algorithmic bias in AI-driven ophthalmology and promote more equitable and patient-centered healthcare practices.

Transparency and Explainability

The complexity of AI systems utilized in ophthalmology often results in a lack of transparency and explainability, posing significant ethical challenges. Both clinicians and patients may struggle to comprehend how AI systems reach specific decisions, which can undermine trust and accountability.[122] To address this issue, efforts should focus on enhancing the transparency and explainability of AI algorithms.

One approach to improving transparency is through the development of interpretable AI models. These models are designed to provide insights into the decision-making process of AI algorithms, making it easier for clinicians and patients to understand how predictions are generated.[123] Techniques such as feature visualization, attention mechanisms, and model-agnostic interpretability methods can help elucidate the factors influencing AI predictions.

Furthermore, clear communication about the functioning of AI systems is essential for maintaining confidence in their application. Clinicians should receive training on how to interpret and critically evaluate AI-generated recommendations, ensuring they can effectively incorporate AI insights into their decision-making process.[123] Patients should also be informed about the role of AI in their care and provided with explanations regarding how AI recommendations are generated and utilized.

Human Role in Decision-Making

While AI offers opportunities for increased efficiency and precision in ophthalmology, it should not replace the essential role of human judgment. Human ophthalmologists possess unique skills, expertise, and intuition that are indispensable in clinical decision-making. Therefore, maintaining the central role of human ophthalmologists is crucial to ensuring ethical and responsible AI use.[124]

AI should be viewed as a complementary tool that augments human capabilities rather than supplants them. Human ophthalmologists can leverage AI-generated insights to enhance their diagnostic accuracy, streamline workflows, and optimize treatment plans.[125] By integrating AI into clinical practice in this manner, healthcare providers can capitalize on the strengths of both human and artificial intelligence to deliver the highest quality of care to patients.

Additionally, emphasizing the human touch in patient care is essential for preserving empathy, compassion, and ethical considerations. While AI may excel in data analysis and pattern recognition, it lacks the ability to empathize with patients or consider the broader ethical implications of clinical decisions. Human ophthalmologists play a critical role in addressing these aspects of patient care, ensuring that ethical considerations remain at the forefront of decision-making processes.[124]

Equity and Access to Care

Ethical AI deployment in ophthalmology requires a commitment to equitable access to advanced technologies. One of the primary ethical imperatives in AI deployment in ophthalmology is to address socioeconomic disparities in access to care. Without intervention, there is a risk that AI technologies may primarily benefit affluent populations, exacerbating existing healthcare disparities. Ethical deployment requires proactive measures to ensure that AI-driven ophthalmic care is accessible to individuals across all socioeconomic strata. This might involve implementing subsidies or financial assistance programs to make AI-enabled services more affordable for low-income patients. Additionally, initiatives to integrate AI technology into public healthcare systems can help ensure equitable access for underserved populations. [121]

Ethical considerations also extend to geographical accessibility, particularly for individuals residing in rural or remote areas where access to specialized healthcare services may be limited. AI deployment in ophthalmology should prioritize initiatives aimed at bridging the rural-urban healthcare divide.[126] This could involve deploying mobile clinics equipped with AI diagnostic tools to reach underserved communities, as well as leveraging telemedicine platforms to connect patients with remote ophthalmic specialists. By ensuring that AI-driven care is accessible beyond urban centers, healthcare providers can uphold ethical principles of fairness and inclusivity. Careful consideration must be given to the potential impact of AI on different socioeconomic groups and geographical locations. Initiatives should be undertaken to minimize disparities in access, making AI-driven ophthalmic care accessible and affordable to all.

Future directions

The advent of AI may reshape the field of medicine. There is unprecedented potential for AI to expand scientific inquiry by using neural networks to generate hypotheses and make new discoveries. It is however, extremely important to ensure the generative AI models are accurate and reliable which requires rigorous testing of large data sets. The field of AI in health care also requires a governance and evaluation framework to minimize risks due to fake data analyses.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Kapoor R, Walters SP, Al-Aswad LA. The current state of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64(2):233-240. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.09.002

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Akkara JD, Kuriakose A. Role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in ophthalmology. Kerala J Ophthalmol 2019;31:150-60. doi: 10.4103/kjo.kjo_54_19

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Roach, L. “Artificial Intelligence.” EyeNet Magazine, Nov. 2017, www.aao.org/eyenet/article/artificial-intelligence.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 The ultimate guide to AI in radiology. The Ultimate Guide to AI in Radiology. https://www.quantib.com/the-ultimate-guide-to-ai-in-radiology. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Ting DSW, Lee AY, Wong TY. An Ophthalmologist’s Guide to Deciphering Studies in Artificial Intelligence. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(11):1475-1479. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.014

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436-444. doi:10.1038/nature14539

- ↑ Price WN, Gerke S, Cohen IG. Potential Liability for Physicians Using Artificial Intelligence. JAMA. October 2019. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.15064

- ↑ When AIs Outperform Doctors: Confronting the Challenges of a Tort-Induced Over-Reliance on Machine Learning by A. Michael Froomkin, Ian R. Kerr, Joelle Pineau :: SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3114347. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- ↑ Castelvecchi D. Can we open the black box of AI? Nature International Weekly Journal of Science. https://www.nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/538020a. Published October 5, 2016. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- ↑ Bolukbasi T, Chang K-W, Zou JY, Saligrama V, Kalai AT. Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings. In: Lee DD, Sugiyama M, Luxburg UV, Guyon I, Garnett R, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 29. Curran Associates, Inc.; 2016. pp. 4349–4357. Available: http://papers.nips.cc/paper/6228-man-is-to-computer-programmer-as-woman-is-to-homemaker-debiasing-word-embeddings.pdf

- ↑ Ardila D, Kiraly AP, Bharadwaj S, et al. End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography. Nat Med. 2019;25(6):954-961. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0447-x

- ↑ Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017;542(7639):115-118. doi:10.1038/nature21056

- ↑ Johnston SC. Anticipating and Training the Physician of the Future: The Importance of Caring in an Age of Artificial Intelligence. Acad Med. 2018;93(8):1105-1106. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002175

- ↑ Ting DSJ, Ang M, Mehta JS, Ting DSW. Artificial intelligence-assisted telemedicine platform for cataract screening and management: a potential model of care for global eye health. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(11):1537-1538. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-315025

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):44-56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

- ↑ Tsui, J.C., Wong, M.B., Kim, B.J. et al. Appropriateness of ophthalmic symptoms triage by a popular online artificial intelligence chatbot. Eye (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-023-02556-2

- ↑ Ting DSW, Peng L, Varadarajan AV, et al. Deep learning in ophthalmology: The technical and clinical considerations. Prog Retin Eye Res. April 2019. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.04.003

- ↑ Martin KR, Mansouri K, Weinreb RN, et al. Use of Machine Learning on Contact Lens Sensor-Derived Parameters for the Diagnosis of Primary Open-angle Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;194:46-53. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2018.07.005

- ↑ Li Z, He Y, Keel S, Meng W, Chang RT, He M. Efficacy of a Deep Learning System for Detecting Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy Based on Color Fundus Photographs. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(8):1199-1206. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.01.023

- ↑ Al-Aswad LA, Kapoor R, Chu CK, et al. Evaluation of a Deep Learning System for Identifying Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy Based on Color Fundus Photographs. J Glaucoma. Published online June 21, 2019. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000001319

- ↑ Cerentini A, Welfer D, Cordeiro d’Ornellas M, Pereira Haygert CJ, Dotto GN. Automatic Identification of Glaucoma Using Deep Learning Methods. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;245:318-321.

- ↑ Haleem MS, Han L, Hemert J van, et al. A Novel Adaptive Deformable Model for Automated Optic Disc and Cup Segmentation to Aid Glaucoma Diagnosis. J Med Syst. 2017;42(1):20. doi:10.1007/s10916-017-0859-4

- ↑ Thompson AC, Jammal AA, Medeiros FA. A Deep Learning Algorithm to Quantify Neuroretinal Rim Loss From Optic Disc Photographs. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;201:9-18. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2019.01.011

- ↑ Retinal Image Analysis - Glaucoma. Accessed May 6, 2020. http://www.kalpah.com/RIAG_brochure.pdf

- ↑ Cifuentes-Canorea P, Ruiz-Medrano J, Gutierrez-Bonet R, et al. Analysis of inner and outer retinal layers using spectral domain optical coherence tomography automated segmentation software in ocular hypertensive and glaucoma patients. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0196112. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196112

- ↑ Omodaka K, An G, Tsuda S, et al. Classification of optic disc shape in glaucoma using machine learning based on quantified ocular parameters. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0190012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190012

- ↑ Muhammad H, Fuchs TJ, De Cuir N, et al. Hybrid Deep Learning on Single Wide-field Optical Coherence tomography Scans Accurately Classifies Glaucoma Suspects. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(12):1086-1094. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000000765

- ↑ Asaoka R, Murata H, Hirasawa K, et al. Using Deep Learning and Transfer Learning to Accurately Diagnose Early-Onset Glaucoma From Macular Optical Coherence Tomography Images. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;198:136-145. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2018.10.007

- ↑ Christopher M, Belghith A, Weinreb RN, et al. Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Features Identified by Unsupervised Machine Learning on Optical Coherence Tomography Scans Predict Glaucoma Progression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(7):2748-2756. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-23387

- ↑ Barella KA, Costa VP, Gonçalves Vidotti V, Silva FR, Dias M, Gomi ES. Glaucoma Diagnostic Accuracy of Machine Learning Classifiers Using Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer and Optic Nerve Data from SD-OCT. J Ophthalmol. 2013;2013:789129. doi:10.1155/2013/789129

- ↑ Bizios D, Heijl A, Hougaard JL, Bengtsson B. Machine learning classifiers for glaucoma diagnosis based on classification of retinal nerve fibre layer thickness parameters measured by Stratus OCT. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88(1):44-52. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01784.x

- ↑ Larrosa JM, Polo V, Ferreras A, García-Martín E, Calvo P, Pablo LE. Neural Network Analysis of Different Segmentation Strategies of Nerve Fiber Layer Assessment for Glaucoma Diagnosis. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(9):672-678. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000000071

- ↑ Fu H, Xu Y, Lin S, et al. Segmentation and Quantification for Angle-Closure Glaucoma Assessment in Anterior Segment OCT. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2017;36(9):1930-1938. doi:10.1109/TMI.2017.2703147

- ↑ Niwas SI, Lin W, Bai X, et al. Automated anterior segment OCT image analysis for Angle Closure Glaucoma mechanisms classification. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2016;130:65-75. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.03.018

- ↑ Asaoka R, Murata H, Iwase A, Araie M. Detecting Preperimetric Glaucoma with Standard Automated Perimetry Using a Deep Learning Classifier. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(9):1974-1980. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.05.029

- ↑ Li F, Wang Z, Qu G, et al. Automatic differentiation of Glaucoma visual field from non-glaucoma visual filed using deep convolutional neural network. BMC Med Imaging. 2018;18(1):35. doi:10.1186/s12880-018-0273-5

- ↑ Goldbaum MH, Sample PA, Zhang Z, et al. Using unsupervised learning with independent component analysis to identify patterns of glaucomatous visual field defects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(10):3676-3683. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-1167

- ↑ Andersson S, Heijl A, Bizios D, Bengtsson B. Comparison of clinicians and an artificial neural network regarding accuracy and certainty in performance of visual field assessment for the diagnosis of glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91(5):413-417. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02435.x

- ↑ Bowd C, Weinreb RN, Balasubramanian M, et al. Glaucomatous patterns in Frequency Doubling Technology (FDT) perimetry data identified by unsupervised machine learning classifiers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e85941. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085941

- ↑ Oh E, Yoo TK, Hong S. Artificial Neural Network Approach for Differentiating Open-Angle Glaucoma From Glaucoma Suspect Without a Visual Field Test. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(6):3957-3966. doi:10.1167/iovs.15-16805

- ↑ Goldbaum MH, Lee I, Jang G, et al. Progression of patterns (POP): a machine classifier algorithm to identify glaucoma progression in visual fields. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(10):6557-6567. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8363

- ↑ Yousefi S, Kiwaki T, Zheng Y, et al. Detection of Longitudinal Visual Field Progression in Glaucoma Using Machine Learning. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018;193:71-79. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2018.06.007

- ↑ Akkara JD, Kuriakose A. Review of recent innovations in ophthalmology. Kerala Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018;30(1):54. doi:10.4103/kjo.kjo_24_18

- ↑ Wen JC, Lee CS, Keane PA, et al. Forecasting future Humphrey Visual Fields using deep learning. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0214875. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214875

- ↑ Kazemian P, Lavieri MS, Oyen MPV, Andrews C, Stein JD. Personalized Prediction of Glaucoma Progression Under Different Target Intraocular Pressure Levels Using Filtered Forecasting Methods. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(4):569-577. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.10.033

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Akkara. Role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in ophthalmology. http://www.kjophthal.com/article.asp?issn=0976-6677;year=2019;volume=31;issue=2;spage=150;epage=160;aulast=Akkara. Accessed December 1, 2019.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Habibalahi A, Bala C, Allende A, Anwer AG, Goldys EM. Novel automated non invasive detection of ocular surface squamous neoplasia using multispectral autofluorescence imaging. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(3):540-550. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2019.03.003

- ↑ Yang J-J, Li J, Shen R, et al. Exploiting ensemble learning for automatic cataract detection and grading. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;124:45-57. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2015.10.007

- ↑ Zhang L, Li J, Zhang I, Han H, Liu B, Yang J, et al. Automatic cataract detection and grading using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In: 2017 Presented at: IEEE 14th International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control (ICNSC); 2017. p. 60‐5.

- ↑ Wu X, Huang Y, Liu Z, et al. Universal artificial intelligence platform for collaborative management of cataracts. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(11):1553-1560. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314729

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Liu X, Jiang J, Zhang K, et al. Localization and diagnosis framework for pediatric cataracts based on slit-lamp images using deep features of a convolutional neural network. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0168606. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168606

- ↑ Mohammadi S-F, Sabbaghi M, Z-Mehrjardi H, et al. Using artificial intelligence to predict the risk for posterior capsule opacification after phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(3):403-408. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.09.036

- ↑ Chen Z, Fu H, Lo W-L, Chi Z. Strabismus Recognition Using Eye-Tracking Data and Convolutional Neural Networks. J Healthc Eng. 2018;2018:7692198. doi:10.1155/2018/7692198

- ↑ Gramatikov BI. Detecting central fixation by means of artificial neural networks in a pediatric vision screener using retinal birefringence scanning. Biomed Eng Online. 2017;16(1):52. doi:10.1186/s12938-017-0339-6

- ↑ Reid JE, Eaton E. Artificial intelligence for pediatric ophthalmology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30(5):337-346. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000593

- ↑ Van Eenwyk J, Agah A, Giangiacomo J, Cibis G. Artificial intelligence techniques for automatic screening of amblyogenic factors. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2008;106:64-73.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Abràmoff MD, Lou Y, Erginay A, Clarida W, Amelon R, Folk JC, et al. Improved automated detection of diabetic retinopathy on a publicly available dataset through integration of deep learning. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:5200–6.

- ↑ Van der Heijden AA, Abramoff MD, Verbraak F, van Hecke MV, Liem A, Nijpels G. Validation of automated screening for refer-able diabetic retinopathy with the IDx‐DR device in the Hoorn Diabetes Care System. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2018;96:63–8.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA 2016;316:2402–10.

- ↑ Ting DSW, Pasquale LR, Peng L, et al. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;103(2):167-175.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Ribeiro L, OliveiraCM, Neves C, Ramos JD, Ferreira H, Cunha- Vaz J. Screening for diabetic retinopathy in the central region of Portugal. Added value of automated ‘disease/no disease’ grading. Ophthalmologica. 2015;233:96–103.

- ↑ Leicht, Simon F., et al. "Microaneurysm turnover in diabetic retinopathy assessed by automated RetmarkerDR image analysis-potential role as biomarker of response to ranibizumab treatment." Ophthalmologica 231.4 (2014): 198-203.

- ↑ Raumviboonsuk P, Krause J, Chotcomwongse P, Sayres R, Raman R, Widner K, et al. Deep learning versus human graders for classifying diabetic retinopathy severity in a nationwide screening program. npj Digit Med. 2019;2:25.

- ↑ Ting DSW, Cheung CY-L, Lim G, et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning System for Diabetic Retinopathy and Related Eye Diseases Using Retinal Images From Multiethnic Populations With Diabetes. JAMA. 2017;318(22):2211. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.18152.

- ↑ Abramoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, et al. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digit Med 2018;1:1–8.

- ↑ Tufail A, Kapetanakis VV, Salas-Vega S, Egan C, Rudisill C, Owen CG, et al. An observational study to assess if automated diabetic retinopathy image assessment software can replace one or more steps of manual imaging grading and to determine their cost- effectiveness. Health Technol Assess (Rockv).2016;20:1–72. xxviii

- ↑ Rajalakshmi R, Subashini R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. Automated diabetic retinopathy detection in smartphone-based fundus photography using artificial intelligence. Eye 2018;32:1138.

- ↑ Bhaskaranand M, Ramachandra C, Bhat S, Cuadros J, Nittala MG, Sadda S, et al. Automated Diabetic Retinopathy Screening and Monitoring Using Retinal Fundus Image Analysis. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2016;10:254-61.

- ↑ Ipp E, Liljenquist D, Bode B, Shah VN, Silverstein S, Regillo CD, Lim JI, Sadda S, Domalpally A, Gray G, Bhaskaranand M, Ramachandra C, Solanki K; EyeArt Study Group. Pivotal Evaluation of an Artificial Intelligence System for Autonomous Detection of Referrable and Vision-Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Nov 1;4(11):e2134254. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Dec 1;4(12):e2144317. PMID: 34779843; PMCID: PMC8593763.

- ↑ Lim JI, Regillo CD, Sadda SR, Ipp E, Bhaskaranand M, Ramachandra C, Solanki K, EyeArt Study Sugbroup. Artificial Intelligence Detection of Diabetic Retinopathy: Subgroup Comparison of the EyeArt System with Ophthalmologists' Dilated Exams . Ophthalmology Science 2022; In Press.

- ↑ Ataer-Cansizoglu E, Bolon- Canedo V, Campbelll JP, et al. Computer-based image analysis for plus disease diagnosis in retinopathy of prematurity: performance of the ‘‘i-ROP’’ system and image features associated with expert diagnosis. TransVis Sci Tech. 2015; 4(6):5, doi:10.1167/tvst.4.6.5.

- ↑ Xiao S, Bucher F, Wu Y, et al. Fully automated, deep learning segmentation of oxygen-induced retinopathy images. JCI Insight. 2017;2(24):e97585. Published 2017 Dec 21. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.97585.

- ↑ Taylor S, Brown JM, Gupta K, et al. Monitoring disease progression with a quantitative severity scale for retinopathy of prematurity using deep learning. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019.

- ↑ Brown JM, Campbell JP, Beers A, et al. Automated diagnosis of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity using deep convolutional neural networks. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:803–10.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Wittenberg LA, Jonsson NJ, Chan RV, Chiang MF. Computer-based image analysis for plus disease diagnosis in retinopathy of prematurity. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012;49(1):11–20. doi:10.3928/01913913-20110222-01

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Wallace DK, Freedman SF, Zhao Z, Jung S. Accuracy of ROPtool vs Individual Examiners in Assessing Retinal Vascular Tortuosity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(11):1523–1530.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Swanson C, Cocker KD, Parker KH, Moseley MJ, Fielder AR. Semiautomated computer analysis of vessel growth in preterm infants without and with ROP. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(12):1474–1477. doi:10.1136/bjo.87.12.1474

- ↑ Wang J, Ju R, Chen Y, et al. Automated retinopathy of prematurity screening using deep neural networks. EBioMedicine 2018; 35:361 – 368.

- ↑ Redd TK, Campbell JP, Brown JM, et al. Evaluation of a deep learning image & assessment system for detecting severe retinopathy of prematurity. Br J Ophthalmol 2018; 2018-313156.

- ↑ Rani P, Elagiri Ramalingam R, Rajamani KT, et al. Multiple instance learning: robust validation on retinopathy of prematurity. Int J Ctrl Theory Appl 2016; 9:451 – 459.

- ↑ Brown JM, Campbell JP, Beers A, et al. Automated diagnosis of plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity using deep convolutional neural networks. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018; 136:803–810.

- ↑ Worrall DE, Wilson CM, Brostow GJ. Automated Retinopathy of Prematurity Case Detection with Convolutional Neural Networks. Deep Learning and Data Labeling for Medical Applications Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2016:68-76. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46976-8_8.

- ↑ Bolon-Canedoa V, Ataer-Cansizoglub E, Erdogmusb D, et al. Dealing with inter-expert variability in retinopathy of prematurity: a machine learning approach. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2015; 122:1–15.

- ↑ Wallace DK, Zhao Z, Freedman SF. A pilot study using ‘ROPtool’ to quantify plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2007; 11:381 – 387.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Gelman R, Jiang L, Du YE, et al. Plus disease in retinopathy of prematurity: pilot study of computer-based and expert diagnosis. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2007; 11:532 – 540.

- ↑ Burlina PM, Joshi N, Pekala M, Pacheco KD, Freund DE, Bressler NM. Automated grading of age-related macular degeneration from color fundus images using deep convolutional neural networks. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:1170‐6.

- ↑ Grassmann F, Mengelkamp J, Brandl C, Harsch S, Zimmermann ME, Linkohr B, et al. A deep learning algorithm for prediction of age-related eye disease study severity scale for age-related macular degeneration from color fundus photography. Ophthalmology 2018;125:1410-20.

- ↑ Akkara J, Kuriakose A. Role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in ophthalmology. Kerala Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;31(2):150-160.

- ↑ Lee CS, Tyring AJ, Deruyter NP, Wu Y, Rokem A, Lee AY. Deep-learning based, automated segmentation of macular edema in optical coherence tomography. Biomed Opt Express. 2017;8(7):3440–3448. Published 2017 Jun 23. doi:10.1364/BOE.8.003440

- ↑ Roy AG, Conjeti S, Karri SPK, et al.ReLayNet: retinal layer and fluid segmentation of macular optical coherence tomography using fully convolutional networks. Biomed Opt Express. 2017;8(8):3627-3642.

- ↑ Schlegl T, Waldstein SM, Bogunovic H, et al. Fully Automated Detection and Quantification of Macular Fluid in OCT Using Deep Learning. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(4):549e58

- ↑ Venhuizen FG, van Ginneken B, Liefers B, et al. Deep learning approach for the detection and quantification of intraretinal cystoid fluid in multivendor optical coherence tomography. Biomed Opt Express. 2018;9(4):1545-1569.

- ↑ Kermany DS, Goldbaum M, Cai W, et al. Identifying Medical Diagnoses and Treatable Diseases by Image-Based Deep Learning. Cell. 2018;172(5). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.010.

- ↑ Fauw JD, Ledsam JR, Romera-Paredes B, et al. Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nature Medicine. 2018;24(9):1342-1350. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0107-6.

- ↑ Bogunovic H, Waldstein SM, Schlegl T, et al.Prediction of Anti-VEGF Treatment Requirements in Neovascular AMD Using a Machine Learning Approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(7):3240e8.

- ↑ Rohm M, Tresp V, Muller M, et al. Predicting Visual Acuity by Using Machine Learning in Patients Treated for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(7):1028e36

- ↑ Treder M, Lauermann JL, Eter N. Automated detection of exudative age-related macular degeneration in spectral domain optical coherence tomography using deep learning. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2018;256:259–65. 10.1007/s00417-017-3850-3

- ↑ Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Software.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-software-medical-device. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- ↑ Dow ER, Keenan TDL, Lad EM, Lee AY, Lee CS, Loewenstein A, Eydelman MB, Chew EY, Keane PA, Lim JI; Collaborative Community for Ophthalmic Imaging Executive Committee and the Working Group for Artificial Intelligence in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. From Data to Deployment: The Collaborative Community on Ophthalmic Imaging Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2022 May;129(5):e43-e59. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.01.002. Epub 2022 Jan 10. PMID: 35016892; PMCID: PMC9859710.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Brummen A, Owen J, et al. Artificial intelligence automation of eyelid and periorbital measurements. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2021;62:2149. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.05.007

- ↑ Simsek I & Sirolu C. Analysis of surgical outcome after upper eyelid surgery by computer vision algorithm using face and facial landmark detection. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259(10):3119-3125. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05219-8.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Liu TYA, Ting DSW, Yi PH, et al. Deep Learning and Transfer Learning for Optic Disc Laterality Detection: Implications for Machine Learning in Neuro-Ophthalmology. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020;40(2):178-184. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000827

- ↑ Jang Y, Son J, Park KH, Park SJ, Jung KH. Laterality Classification of Fundus Images Using Interpretable Deep Neural Network. J Digit Imaging. 2018;31(6):923-928. doi:10.1007/s10278-018-0099-2

- ↑ Milea D, Najjar RP, Zhubo J, et al. Artificial Intelligence to Detect Papilledema from Ocular Fundus Photographs. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1687-1695. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1917130

- ↑ Biousse V, Newman NJ, Najjar RP, et al. Optic Disc Classification by Deep Learning versus Expert Neuro-Ophthalmologists. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(4):785-795. doi:10.1002/ana.25839

- ↑ Levin LA, Rizzo JF 3rd, Lessell S. Neural network differentiation of optic neuritis and anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(9):835-839. doi:10.1136/bjo.80.9.835

- ↑ Feldon SE, Levin L, Scherer RW, et al. Development and validation of a computerized expert system for evaluation of automated visual fields from the Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial. BMC Ophthalmol. 2006;6:34. Published 2006 Nov 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-6-34

- ↑ Wen JC, Lee CS, Keane PA, et al. Forecasting future Humphrey Visual Fields using deep learning. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214875. Published 2019 Apr 5. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214875

- ↑ Yang HK, Kim YJ, Sung JY, Kim DH, Kim KG, Hwang JM. Efficacy for Differentiating Nonglaucomatous Versus Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy Using Deep Learning Systems. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;216:140-146. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2020.03.035

- ↑ Waisberg E, Ong J, Kamran SA, Paladugu P, Zaman N, Lee AG, Tavakkoli A. Transfer learning as an AI-based solution to address limited datasets in space medicine. Life Sci Space Res (Amst). 2023 Feb;36:36-38.

- ↑ Waisberg E, Ong J, Masalkhi M, Zaman N, Kamran SA, Sarker P, Lee AG, Tavakkoli A. Generative Pre-Trained Transformers (GPT) and Space Health: A Potential Frontier in Astronaut Health During Exploration Missions. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2023 Aug;38(4):532-536.

- ↑ Masalkhi, M., Ong, J., Waisberg, E. et al. Deep learning in ophthalmic and orbital ultrasound for spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS). Eye (2023).

- ↑ UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence (2023).

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2021). Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Chatterjee, Sheshadri, and N. S. Sreenivasulu. "Personal data sharing and legal issues of human rights in the era of artificial intelligence: Moderating effect of government regulation." International Journal of Electronic Government Research (IJEGR) 15.3 (2019): 21-36.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 Cate, Fred H., "Government Data Mining: The Need for a Legal Framework" (2008). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 150. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/150

- ↑ Jose Ramon Saura, Domingo Ribeiro-Soriano, Daniel Palacios-Marqués, Assessing behavioral data science privacy issues in government artificial intelligence deployment, Government Information Quarterly, Volume 39, Issue 4, 2022, 101679, ISSN 0740-624X.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Timan, T., Mann, Z. (2021). Data Protection in the Era of Artificial Intelligence: Trends, Existing Solutions and Recommendations for Privacy-Preserving Technologies. In: Curry, E., Metzger, A., Zillner, S., Pazzaglia, JC., García Robles, A. (eds) The Elements of Big Data Value. Springer, Cham.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 Mittermaier, M., Raza, M.M. & Kvedar, J.C. Bias in AI-based models for medical applications: challenges and mitigation strategies. npj Digit. Med. 6, 113 (2023).

- ↑ Nazer LH, Zatarah R, Waldrip S, Ke JXC, Moukheiber M, Khanna AK, Hicklen RS, Moukheiber L, Moukheiber D, Ma H, Mathur P. Bias in artificial intelligence algorithms and recommendations for mitigation. PLOS Digit Health. 2023 Jun 22;2(6):e0000278.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Abràmoff MD, Tarver ME, Loyo-Berrios N, Trujillo S, Char D, Obermeyer Z, Eydelman MB; Foundational Principles of Ophthalmic Imaging and Algorithmic Interpretation Working Group of the Collaborative Community for Ophthalmic Imaging Foundation, Washington, D.C.; Maisel WH. Considerations for addressing bias in artificial intelligence for health equity. NPJ Digit Med. 2023 Sep 12;6(1):170.

- ↑ Kiseleva A, Kotzinos D, De Hert P. Transparency of AI in Healthcare as a Multilayered System of Accountabilities: Between Legal Requirements and Technical Limitations. Front Artif Intell. 2022 May 30;5:879603.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Bernal J, Mazo C. Transparency of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Insights from Professionals in Computing and Healthcare Worldwide. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(20):10228.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Andrada, G., Clowes, R. W., & Smart, P. R. (2022). Varieties of transparency: Exploring agency within AI systems. Ai & Society, 1–11.

- ↑ Jin K, Ye J. Artificial intelligence and deep learning in ophthalmology: Current status and future perspectives. Adv Ophthalmol Pract Res. 2022 Aug 24;2(3):100078.

- ↑ Damoah, I. S., Ayakwah, A., & Tingbani, I. (2021). Artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced medical drones in the healthcare supply chain (HSC) for sustainability development: A case study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 328, 129598.