Corneal Tissue Addition Techniques: CAIRS and CTAK

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

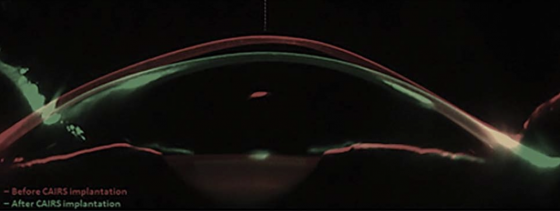

Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (CAIRS) are stromal implants derived from donor corneal tissue used in the treatment of corneal ectasias, including keratoconus. CAIRS belongs to a broader family of corneal addition techniques aimed at flattening the cone and regularizing corneal shape, including synthetic intrastromal corneal ring segments (ICRS) and Corneal Tissue Addition Keratoplasty (CTAK). Unlike ICRS, which are made of rigid synthetic polymers, CAIRS offers a biocompatible alternative that integrates more naturally with host tissue.[1] While CTAK involves implanting gamma-irradiated donor segments that are customized to individual topography, processed by CorneaGen, and implanted exclusively with a femtosecond laser[2], CAIRS segments can be prepared and implanted manually or with femtosecond guidance. As an emerging technique, CAIRS currently encompasses a variety of surgical approaches, contributing to its adaptability across different clinical settings.

History

CAIRS was introduced in 2018 by Dr. Soosan Jacob as a biocompatible alternative to synthetic ICRS, which are associated with complications including infection, extrusion, and stromal melt.[1] Dr. Jack Parker has since modified the technique by developing alternative insertion methods, including manual implantation and preimplantation dehydration, which enhance surgical flexibility and broaden accessibility.[3] Dr. Jacob has continued to innovate by expanding the customization potential of CAIRS through the use of multiple segments, tailored arc lengths, variable thicknesses, and strategic placement, allowing implants to better match the patient’s cone morphology and achieve targeted corneal flattening.[4]

Contraindications and Indications

Indications

- Keratoconus[1][4][5][6]

- Post LASIK corneal ectasia[5]

- Intrastromal Corneal Ring Segments Extrusion[7]

Alongside the above listed diagnosis, additional criteria were observed in some studies: unsatisfactory level of visual correction with spectacles/contact lenses[5], contact lens intolerance[5][6][8], and older than 18.[6][8][9]

Contraindications

- Central scarring or opacity[1][5][6][8][9][10]

- Severely thin corneas ( <320 µm)[1] - (<350 )[11]

- Active corneal infection or inflammation[1][5][9][10]

- Autoimmune diseases or connective tissue disease[1][5][9][10] [11]

- Pregnancy and/or lactating[9][10][11]

Preoperative Evaluation

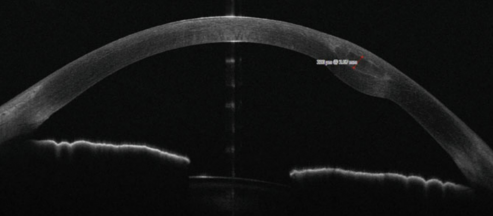

Preoperative evaluation commonly involves measurement of uncorrected and corrected distance visual acuity (UDVA and CDVA), slit-lamp examination, corneal topography/tomography including keratometry values such as Kmax and Kmean, and anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT).[1][12][13]

Surgical planning for CAIRS spans a broad spectrum, ranging from early uniform techniques to evolving nomogram-based strategies. Initial surgeries were guided by corneal topography and pachymetry but followed a uniform nomogram, as described by Jacob in 2018[1]. Today, surgeons employ a range of planning methods, some utilizing emerging nomograms such as those proposed by Jacob[4], the Istanbul group[11], and Awwad[5]. The Jacob nomogram incorporates parameters such as cone location, eccentricity, keratometry values, and asymmetric patterns to customize the number, arc length, and thickness of segments.[4] The Istanbul nomogram mainly relies on cone location (centered/decentered) to guide planning. [11] Lastly, the Awwad nomogram, which was adapted from an ICRS nomogram, is informed by corneal topography, segmental tomography, and clinical judgment.[5] While these nomograms offer structured guidance, surgeon judgment and individualized interpretation remain critical, as the morphological variability of keratoconus often necessitates tailored decision-making. There is currently no universally accepted CAIRS nomogram.[12]

Donor Tissue and Segment Preparation

CAIRS segments are derived from human donor corneas, and their preparation may vary depending on the surgeon’s preference and available resources. There are two main sourcing and preparation pathways:

- Pre-packaged segments from specialized eye banks: Eye banks such as Lions VisionGift offer pre-cut, sterilized stromal segments (e.g., KeraNatural®) that come ready-to-use. These shelf-stable implants eliminate the need for intraoperative customization and reduce variability in graft quality. These pre-made segments can still be cut to surgeon's preference.[9]

- Custom-prepared donor tissue: Corneal rims obtained from eye banks are manually processed by the surgical team. After removal of the epithelium, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium, the remaining stromal tissue is trephined to create ring segments. These segments can then be trimmed and customized according to the patient’s corneal topography. Surgeons may adjust anywhere from just the arc length to thickness, taper, or curvature based on the cone's location and severity.[4]

In the case of CTAK, preserved, gamma-irradiated, sterilized tissue (CorneaGen) is rinsed with a balanced salt solution before being centered on a fixation device to the femtosecond laser.[2] Arc length, width, and thickness are customized for each patient case, as well as implantation depth and location, using topography, elevation, and thickness map parameters. The segment is then placed in a corneal storage solution until implantation into the recipient.[2]

Regardless of the source, segments can undergo additional preparation steps before implantation. For instance, extended air-drying techniques like the "corneal jerky" method are used to temporarily dehydrate the tissue, making it stiffer and easier to insert through narrow stromal tunnels.[14] This lowers surgery times and allows for easier insertion of larger segments that can correct more severe keratoconus.[3][14] Segments may also be briefly stained with trypan blue or riboflavin (vitamin B2) to enhance intraoperative visibility. Riboflavin is notably used in surgeries with combined CAIRS and corneal cross-linking (CXL), where it functions as both a visualizer and a photosensitizer. [1][3]

Surgical Techniques

Channel Creation:

Channels are created using a Femtosecond laser or manual dissection. Depth of the channel is more commonly determined by going 35-70% depth of total cornea thickness.[12] There are also reports of going a fixed depth(i.e. 250 um) from the corneal surface.[5][13] The entry incision is on the steep axis or superiorly. The second incision is often 180 degrees from the first. Channel creations can range from an inner diameter of 4-6.5 mm to an outer diameter of 6.1-8mm.[12] Ranges can be based on scotopic pupil size and location of the cone as determined by OCT elevation tomography.[13]

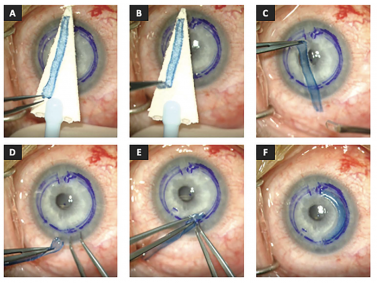

Segment insertion | Hydrated Method[1]:

- A hydrated segment is introduced to one end of the channel

- Forceps or custom instruments (e.g., Y-rod, Sinskey hook) can be used to pull and/or adjust a hydrated segment into the channel along the stromal curvature

- The incision is hydrated to ensure sealing, and sutures are rarely necessary

Hydrated segments maintain their natural flexibility and native thickness, allowing for gentle conformity to the corneal curvature. However, this pliability can make insertion more technically challenging, as the segments may fold or twist within the tunnel.[14] Improper orientation during insertion can also lead to malalignment of corneal layers, particularly if the segment is inadvertently placed upside down. To mitigate this, one technique involves marking Bowman’s layer with a sterile surgical marker immediately after excising the deepithelialized corneal tissue.[4]

Segment insertion | Dehydrated Method “Corneal Jerky”[14][3]:

- Segments are dried for 20[3] - 75[14] minutes before implantation. The recipient's corneal surface is well dried before the dried segment is introduced[3]

- The dried segment can be maneuvered into the segment similarly to an ICRS due to its stiff nature with a Y-rod or Sinskey hook[3][14]

- Once in place, the dehydrated segment fully rehydrates after irrigation of the eye with a balanced salt solution[14]

Dehydrated segments, being physically smaller and stiffer, allow for faster implantation and facilitate the use of larger segments without additional trauma to the stromal tunnel. Awwad et. al. (2023)[14] reported that the dehydrated method reduced intraoperative time by nearly threefold.

Post-Operative Evaluation

Postoperative Care

- Topical antibiotic, generally QID x 1 to 2 weeks

- Topical steroid, generally QID then tapered over 4-6 weeks

- Bandage contact lens can be used for a few days post-op[5][14]

Postoperative monitoring typically involves topography/tomography and anterior segment OCT to assess corneal shape changes and segment positioning. UCVA, CDVA, Kmax, and Kmean can be re-evaluated as well to track visual and refractive outcomes.[11][9][14][16]

A Note About Crosslinking

Dr. Jacob performed CXL concurrently during her initial CAIRS cases,[1] but the timing and use of cross-linking varies among surgeons. Indications often include a history of documented progression or planned combination therapy to enhance long-term stability. While concurrent CXL can help maintain postoperative corneal flattening[1], some studies suggest that performing CXL preoperatively may reduce the flattening effect of CAIRS due to increased stromal stiffness, thereby reducing the efficacy of the CAIRS procedure.[10]

Risk and Complications

CAIRS has been associated with few and generally mild complications. The most commonly reported issues include transient dry eye symptoms and small intratunnel deposits, both of which were clinically insignificant and non-progressive.[8][9] In the longest clinical trial to date, all visual and topographic parameters stabilized by six months and were maintained over a three-year follow-up period, with no reported cases of corneal melting or segment extrusion.[9]

A few cases of unique complications have been reported. A single case of graft dislocation toward the incision site was reported and was successfully repositioned within the first postoperative week.[8] In another case involving a patient with severe preexisting atopy, anterior stromal melt was observed.[17] Photic disturbances were also rare. Only one patient across the reviewed studies experienced glare or halos[6], a rate notably lower than with synthetic ICRS, where such symptoms are common.[18] This reduced photic disturbance may be attributed to the optical compatibility between allogenic segments and the host stroma, as well as the absence of rigid implant edges.[12]

CTAK has also been associated with few and generally mild complications. In a 2023 study by Greenstein et al., CTAK was performed on twenty-one eyes of 18 patients (11 male, 7 female) with a mean age of 34.9 years, and they were followed for 6 months; meaningful improvements in visual acuity and topography were seen in all patients except for one case, where there was a partial tear of the channel wall during insertion of the tissue inlay.[2] The authors note that this was the only case in which a full-thickness ring segment was placed, and that improvements in dissection and insertion instrumentation may minimize the risk for this specific complication.[2]

Theoretically, stromal rejection is possible due to the allogenic nature of the tissue; however, the risk appears to be lower than that associated with deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), which itself carries a low rejection rate.[12]

Prognosis and Outcomes

CAIRS implantation has consistently demonstrated improvement in both refractive and topographic parameters. According to a systematic review by Levy et al. (2025)[12], mean uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) improved from 0.83 ± 0.15 to 0.40 ± 0.08 logMAR, and corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) improved from 0.52 ± 0.22 to 0.19 ± 0.09 logMAR (p = 0.01 for both). Spherical equivalent (SE) decreased from −7.09 D to −2.34 D, while Kmax and Kmean were reduced from 57.8 ± 1.09 D to 53.57 ± 2.66 D and 49.27 ± 0.28 D to 45.30 ± 1.46 D, respectively.

According to Greenstein et al. (2023), CTAK has also shown improvements in refractive and topographic parameters[2], as outlined below:

Refractive

- mean UDVA improved from 1.21 ± 0.35 LL (20/327) preoperatively to 0.61 ± 0.25 LL (20/82) at 6 months postoperatively (P < .001).

- CDVA improved from 0.63 LL (20/82) preoperatively to 0.34 ± 0.21 LL (20/43) at 6 months postoperatively (P = .002).

- MRSE (Mean Refractive Spherical Equivalent) improved from 6.25 ± 5.45 diopters (D) preoperatively to 1.61 ± 3.33 D 6 months postoperatively.

Topographic

- Kmean flattened by 8.44 D, from 58.43 ± 9.06 D preoperatively to 49.99 ± 7.57 D at 6 months postoperatively (P = .002).

- Kmax flattened by 6.91 D, from 72.21 ± 12.71 D preoperatively to 65.30 ± 13.56 D at 6 months postoperatively; however, this change failed to reach statistical significance (P = .096).

From a biomechanical standpoint, both CAIRS and CTAK can be implanted in thinner corneas and at shallower depths than synthetic rings, allowing for greater correction of severe keratoconus[14]. It has also been used successfully to replace extruded or failed synthetic ICRS.[7][16] CAIRS and CTAK are appropriate for mild to moderate keratoconus and may delay or even eliminate the need for more invasive procedures like deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) in advanced cases.[3]

The allogenic segments are implanted in the avascular, low-cellularity stromal layer, which minimizes fibrotic adhesion and supports surgical reversibility. Implantation in this layer also reduces the risk of corneal melt[19], acute stromal necrosis[19], and corneal neovascularization.[5] Receiving CAIRS does not preclude future interventions such as DALK.[20]

Economically, CAIRS and CTAK offer several cost advantages. A single donor cornea can be used to produce multiple segments. The central disc may be used for DALK and DMEK in split cornea transplantation, or penetrating keratoplasty if the epithelium is preserved, while the peripheral corneoscleral rim can be utilized for limbal stem cell harvesting.[21] Additionally, manual dissection techniques used in CAIRS eliminate the need for femtosecond lasers, making the procedure more feasible in resource-limited settings.[12]

Both CAIRS and CTAK surgical procedures have less steep learning curves compared to traditional penetrating keratoplasty and deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), further emphasizing their usefulness in a clinical setting.

Future Direction

The versatility of CAIRS continues to expand as surgical experience grows and its indications broaden. One of the most promising developments is the customization of CAIRS segments, allowing for tailored arc lengths, thicknesses, and positioning based on individual corneal topography. This level of personalization makes CAIRS particularly advantageous in cases of asymmetric or decentered cones, where traditional ring segments may underperform.[4] The additional sterilization step and increased precision of donor segment measurements as a result of CorneaGen processing gives CTAK its own unique benefits.[2]

CAIRS remains a relatively new intervention with limited long term data, the longest follow-up currently reported at three years.[9] Continued efforts to standardize nomograms, refine tissue preparation protocols, and conduct large-scale longitudinal studies will be essential to establish the long-term role of procedures like CAIRS and CTAK in the management of corneal ectasias.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Jacob S, Patel SR, Agarwal A, et al. Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (CAIRS) Combined With Corneal Cross-linking for Keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 2018;34(5):336–344.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Greenstein SA, Yu AS, Gelles JD, Eshraghi H, Hersh PS. Corneal tissue addition keratoplasty: new intrastromal inlay procedure for keratoconus using femtosecond laser-shaped preserved corneal tissue. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2023;49(7):740-746. doi:10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000001187

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Parker JS, Dockery PW, Jacob S. Preimplantation Dehydration for Corneal Allogeneic Intrastromal Ring Segment (CAIRS) Implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2021;47(11):e37–e39.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Jacob S, Agarwal A, Awwad ST, Mazzotta C, Parashar P, Jambulingam S. Customized corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS) for keratoconus with decentered asymmetric cone. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;72(5):988–993. doi:10.4103/IJO.IJO_1988_23

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 Bteich Y, Assaf JF, Abou Mrad A, et al. Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (CAIRS) for Corneal Ectasia: A Comprehensive Segmental Tomography Evaluation. J Refract Surg. 2023;39(12):e987–e993.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Kirgiz A, Atik BK, Emul M, Taskapili M. Clinical Outcomes of Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Corneal Allogeneic Intrastromal Ring Segment (CAIRS) in the Treatment of Keratoconus. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2024. doi:10.1111/ceo.14411

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Susanna BN, Forseto AS, Moriyama AS, et al. Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Customized Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments in Patients With Keratoconus After Intrastromal Corneal Ring Segment Explantation: Prospective Case Series. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2024;50(2):267–273.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Nacaroglu SA, Yesilkaya EC, Keskin Perk FFN, Tanriverdi C, Taneri S, Kilic A. Efficacy and Safety of Intracorneal Allogeneic Ring Segment Implantation in Keratoconus: 1-Year Results. Eye (Lond). 2023;37:3807–3812. doi:10.1038/s41433-023-02618-5

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Keskin Perk FFN, Tanriverdi C, Karaca ZY, Tran KD, Kilic A. Long-Term Results of Sterile Corneal Allograft Ring Segments Implantation in Keratoconus Treatment. Cornea. 2025;44(4):475–482.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Yucekul B, Tanriverdi C, Taneri S, Keskin Perk FFN, Karaca ZY, Kilic A. Effect of Corneal Allogeneic Intrastromal Ring Segment (CAIRS) Implantation Surgery in Patients With Keratoconus According to Prior Corneal Cross-Linking Status. J Refract Surg. 2024;40(6):e392–e397.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Haciagaoglu S, Tanriverdi C, Keskin FFN, Tran KD, Kilic A. Allograft Corneal Ring Segment for Keratoconus Management: Istanbul Nomogram Clinical Results. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023;33(2):689–696. doi:10.1177/11206721221142995

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 Levy I, Mukhija R, Nanavaty MA. Corneal Allogeneic Intrastromal Ring Segments: A Literature Review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2025;19:1317–1327.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Benz EE, Tappeiner C, Goldblum D, Kyroudis D. Outcomes After Implantation of KeraNatural, a Sterile Corneal Allograft Intrastromal Ring Segment (CAIRS), in Eyes With Keratoconus. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2025;242(5):476–484.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 Awwad ST, Jacob S, Assaf JF, Bteich Y. Extended Dehydration of Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments to Facilitate Insertion: The Corneal Jerky Technique. Cornea. 2023;42(10):1367–1372.

- ↑ Ravishankar V, Jacob S. Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (C.A.I.R.S). In: Armia A, Mazzotta C, eds. Keratoconus: Current and Future State-of-the-Art. Cham: Springer; 2022: 167-176. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-51755-5_29

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Asfar KE, Bteich Y, Abou Mrad A, et al. Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (CAIRS) Versus Synthetic Segments: A Single Segment Comparative Analysis Using Propensity Score Matching. J Refract Surg. 2024;40(4):e210–e217.

- ↑ Awwad ST, Asfar KE, Gendy J, Jacob S, Assaf JF. Anterior Stromal Melt With Corneal Allogeneic Intrastromal Ring Segments in a Patient With Severe Atopy. Cornea. 2025;44(1):96–98.

- ↑ Jenkins MD, Alarcon A, Ribeiro MF, et al. Preclinical Methods to Evaluate Photic Phenomena in Intraocular Lenses. Optica. 2024;11(4):512–520.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kozhaya K, Mehanna CJ, Jacob S, Saad A, Jabbur NS, Awwad ST. Management of Anterior Stromal Necrosis After Polymethylmethacrylate ICRS: Explantation Versus Exchange With Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments. J Refract Surg. 2022;38(4):256-263. doi:10.3928/1081597X-20220223-01

- ↑ Ravishankar V, Jacob S. Corneal Allogenic Intrastromal Ring Segments (C.A.I.R.S). In: Armia A, Mazzotta C, eds. Keratoconus: Current and Future State-of-the-Art. Cham: Springer; 2022: 167-176. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-51755-5_29

- ↑ Jacob S. Custom-shaped CAIRS for personalized treatment of Keratoconus. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2025;73(1):3-5. doi:10.4103/IJO.IJO_2589_24