Eccrine Sweat Gland Carcinoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

- Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma (ESGC): ICD-10-CM L74.9

Disease

Humans have the highest density of eccrine sweat glands of any mammal. Eccrine sweat glands (ESG) arise from ectodermal appendages and can be found in differential densities throughout the human body. The highest concentrations in humans are found in the axillary region and the eyelids/orbits, and the primary function being thermoregulation (“efficient evaporative eccrine cooling”). Dysfunction or loss through disease/injury leads to significant clinical morbidity.

ESGC is an extremely rare malignancy (accounting for < 0.01% of diagnosed cutaneous malignancies), most frequently found on the eyelids, of the elderly.

- ESGC classification schemes (bold indicates relatively common types):

- Benign ESGC

- Poroma

- Hidradenoma

- Spiradenoma

- Cylindroma

- Syringometaplasia

- Syringoma

- Syringofibroadenoma

- Chondroid syringoma

- Malignant ESGC (locally aggressive with high recurrence rate)

- Porocarcinoma

- Stains positive for cytokeratins (CKs) and PAS

- Syringoid eccrine carcinoma

- Stains positive for Cytokeratins (CK), PAS, and D-PAS

- Adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Mucinous carcinoma

- Stains positive for PAS

- Most commonly arise on the eyelids and head/neck regions

- Male predilection (average age of diagnosis: 62 years)

- Endocrine Mucin Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma (EMPSGC)

- Elderly female predilection (lower eyelid)

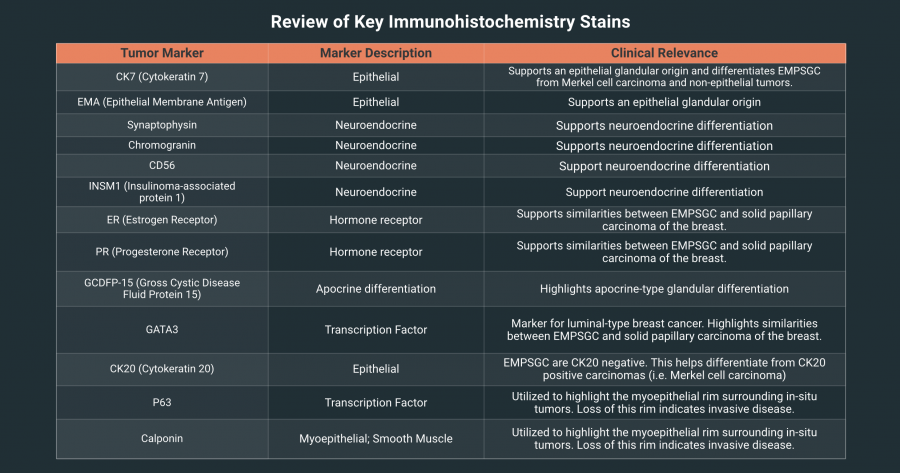

- Positive staining for CK7, Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA), Neuroendocrine markers (synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD56, INSM1), +/- ER, PR, apocrine related markers.

- Negative staining for CD20 (distinguishing from Merkel Cell Carcinoma, and other CD20+ metastatic carcinomas)

- Hidradenocarcinoma

- Malignant spiradenoma carcinoma

- Malignant cylindroma

- Microcystic adnexal carcinoma

- Ductal papillary adenocarcinoma

- Porocarcinoma

- Unclassifiable sweat gland tumors

- Ductal ESGC

- Well-differentiated "signet-ring" ductal carcinoma

- Poorly-differentiated "histiocytoid-variant" ductal carcinoma

- Basaloid eccrine carcinoma

- Clear cell eccrine carcinoma

- Ductal ESGC

- Benign ESGC

Epidemiology

Incidence/Prevalence: Extremely rare

Risk Factors

- Age (most commonly diagnosed in 6th-8th decades of life)

- Family history

- Immunosuppression

- Ultraviolet radiation

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

(not mutually exclusive and capable of having various combinations of the below)

- Progressive painless infiltration (redness, swelling) or growth (periorbital mass) of one or both eyelids

- Ocular or facial pain

- Associated pain with metastases (lymph nodes, parotid gland, bone, skin, lung, and/or liver)

- "Monocle-like" appearance to the affected eyelid(s)

- Brown, blue, and/or red nodule, papule, or ulcerative lesion anywhere on the body but most commonly:

- Lower extremities

- Head and neck

- Upper extremities

Differential Diagnosis

- Adult orbital tumors:

- Metastatic tumors

- Lymphoid tumors

- Cavernous hemangiomas

- Mesenchymal tumors

- Neurilemmoma

- Neurofibroma

- Adult extraconal orbital lesions

- Mucocele

- Localized neurofibroma

- Optic nerve sheath meningioma

- Based on histology:

- Cutaneous neoplasms containing signet-ring cells:

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Melanocytic tumors

- Cylindroma

- Lymphoma

- Cutaneous neoplasms containing signet-ring cells:

Diagnostic Procedures

- PET/CT Orbit, MRI Orbit, bone scintigraphy

- Initial imaging for evaluation of a structural abnormalities

- Exenteration with subsequent histological evaluation

- Early diagnosis is paramount but sometimes challenging due to morphological similarity to other common tumors and lack of consistent immunohistochemical markers

Pathology

- Histologically, ESGC closely resembles a general inflammatory process and is nearly identical to that of breast ductal adenocarcinoma, lacrimal gland adenocarcinoma, and salivary gland adenocarcinoma. ESGC is centered on the dermis and composed of tubular structures lined by atypical basaloid cells, with perineural invasion being common. Specific morphology depends on the distinct ESGC subtype entity.

- Associated tumor markers:

- Simple epithelial CKs commonly expressed:

- CKs 7, 8, 18, 19

- Epithelial membrane antigen (EMA)

- Stratified epithelial cytokeratins less commonly expressed:

- CKs 5, 14

- Focally expressed:

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

- S100

- Simple epithelial CKs commonly expressed:

Genetics and Molecular Pathways

- In mouse models, ESG and hair follicle densities have been shown to be inversely regulated by the transcription factor Engrailed1 (En1), which is encoded on a region of mouse chromosome 1.

- In both mouse models and humans, ESG and hair follicle formation share critical, common molecular pathways: canonical Wnt, bone morphogenetic protein, ectodysplasin, sonic hedgehog. The precise differential formation (and underlying molecular mechanisms) of ESG versus hair follicles is poorly understood.

Endocrine Mucin Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma

Disease Entity of EMPSGC

Endocrine mucin‑producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) is a rare, low‑grade malignant sweat gland tumor with dual neuroendocrine differentiation and mucin production.[1] It predominantly affects older adults and women and most commonly manifests in the eyelids and periocular skin, although head and neck involvement is also reported. Clinically, it usually presents as a slow‑growing, painless eyelid nodule or cystic mass, which explains frequent misdiagnosis as a chalazion, inclusion cyst, or even basal cell carcinoma.[2] A systematic review of published cases found an initial histopathologic misdiagnosis rate of approximately 45%.[3][4] EMPSGC is widely regarded as the cutaneous analogue of solid papillary carcinoma of the breast and often represents an in situ precursor that can progress to an invasive mucinous sweat gland carcinoma when the myoepithelial boundary is lost. [5][6][7]

Histopathology

EMPSGC is a predominantly dermis‑centered, well circumscribed, multinodular tumor that can be solid, papillary, cribriform, and frequently, partially cystic.[8] Tumor cells are cytologically bland with abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and finely stippled “salt‑and‑pepper” chromatin typical of neuroendocrine differentiation; pseudo-rosette‑like arrangements may be present. A defining feature of EMPSGC is mucin. Both intra‑ and extracellular mucin is common and highlights with PAS, Mucicarmine, and Alcian blue stains. If there is an invasive mucinous component, tumor margins can be composed of tumor cell clusters within a pool of mucin, or mucin strands only, within the tissue specimen.[3][5]

Tumor cell markers are typically positive for CK7 and epithelial markers (EMA: epithelial membrane antigen), and express neuroendocrine markers (synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD56, INSM1). Other commonly expressed markers include estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), apocrine‑related markers (GCDFP‑15, GATA3). CK20 is negative, which helps distinguish EMPSGC from Merkel cell carcinoma and certain metastatic carcinomas that are CK20‑positive.[9] Importantly, a myoepithelial rim surrounds in situ EMPSGC and can be identified by p63 and calponin; its loss defines transition to invasive mucinous carcinoma. .[3][5]

A combination of tissue morphology, mucin stains, and targeted immunohistochemistry panels (CK7, ER/PR, neuroendocrine markers, GCDFP‑15/GATA3, CK20) can assist in narrowing the differential diagnoses.[10]

Similarities and Differences between Eccrine Sweat Gland Carcinoma and Endocrine Mucin Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma

Endocrine mucin producing sweat gland carcinomas, a subset of eccrine sweat gland carcinoma, share the same eccrine ductal origin and many of the defining characteristics possessed by other ESGC subtypes.[5][8] EMPSGC, however, distinguishes itself as a unique entity through clinical behavior, demographics, and histological features.

EMPSGCs are considered low grade, indolent neoplasms that exhibit slow growth and a favorable prognosis when treated adequately.[8] This behavior directly contrasts to other more aggressive subtypes of ESGC, like porocarcinoma, hidradenocarcinoma, and mucinous carcinoma, which exhibit high rates of local invasion and recurrence.[11] Additionally, metastatic spread of EMPSGC is rarely observed, with very few cases reported in the literature to date, while other sweat gland carcinomas metastasize at higher rates.[3]

Furthermore, the patient population primarily affected by EMPSGC is distinctive compared to other ESGC subtypes. EMPSGC has a predilection for the periorbital region, specifically the lower eyelid of elderly women, whereas other sweat gland carcinomas like mucinous carcinoma predominantly impact males.[5]

EMPSGC may present similarly to other ESGC subtypes, both clinically and histologically, and often resemble other sweat gland neoplasms such as hidradenomas.[5] EMPSGC is made distinguishable by its unique immunohistochemical profile, including the expression of neuroendocrine markers and hormone receptors, as well as by the production of mucin that is not characteristic of all ESGC subtypes.[9]

Management of EMPSGC

Although EMPSGC is typically considered indolent in nature, rare cases of metastasis have been reported; therefore, management should begin with screening for metastatic disease.[12] A complete review of systems and physical examination should be performed to assess for constitutional symptoms like weight loss, fatigue, and lymphadenopathy. Full body imaging can also be utilized to detect metastatic lesions.[12] Finally, because of the similarities between EMPSGC and solid papillary carcinoma of the breast, a clinical breast exam, as well as imaging with mammography and ultrasound, may be utilized to rule out metastatic spread of a breast neoplasm before a definitive diagnosis is made.[4]

Treatment of primary EMPSGC is similar to that of other ESGCs and can be achieved through surgical removal. Wide local excision with a intra-operative frozen section margin clearance of at least 5mm is a common approach used to remove tumors and surrounding tissues. This additionally reduces recurrence rates.[2] Mohs micrographic surgery can also be utilized in cosmetically sensitive areas, like the periorbital region, to attain histologically clear margins and maintain maximal integrity of normal tissue.[2] In more complex or unresectable cases of EMPSGC, targeted hormonal therapy with aromatase inhibitors, GnRH analogs, and other agents can be employed based on the hormone receptor expression of the individual tumor.[13]

Management

General

Management

- First-line intervention: surgical excision with wide margins (skin biopsy)

- Pathological staging using pTNM criteria

- If necessary, orbital exenteration

- If necessary, adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy (e.g. 5-FU)

- Progression of the tumor after surgical resection or failed adjuvant therapies is possible

- PET/CT Orbit, MRI Orbit, bone scintigraphy

- Repeat imaging for evaluating therapeutic effectiveness and tumor recurrences

- Multidisciplinary management team including medical oncologist, surgeon, dermatologist, dermatopathologist, pharmacist, and/or ophthalmologist depending upon location and extent of disease process.

- Due to the rarity of ESGC, no randomized control trials exist examining management options

Prognosis

Protracted course over several years with an overall favorable prognosis with timely intervention in a treatment-responsive tumor. However, an unfavorable prognosis is associated with delayed interventions, metastatic lesions (reaching lymph nodes, parotid gland, bone, skin, lung, and/or liver), and recurrent disease despite conventional surgical excision. Close long-term follow-up recommended. Relative mortality rate is 80%, while the 10-year disease survival rate is 9%.

References

- Zhang L, Ge S, Fan X. A brief review of different types of sweat-gland carcinomas in the eyelid and orbit. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:331–340. Published 2013 Apr 9. doi:10.2147/OTT.S41287

- Kim YM, Kim JW, Oh, DE. A case of Histiocytoid Variant Eccrine Sweat Gland Carcinoma of the Orbit. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011 Feb; 25(1):54-56. Published 2011 Jan 7.

- Kramer TR, Grossniklaus HE, McLean IW, et al. Histiocytoid variant of eccrine sweat gland carcinoma of the eyelid and orbit: report of five cases. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:553–559.

- Seredyka-Burduk M, Burduk PK, Bodnar M, Malukiewicz G, Kopczynski A. Bilateral primary histiocytoid eccrine sweat gland carcinoma of eyelids. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;94:665---68

- The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2017.

- Kamberov YG, Karlsson EK, Kamberova GL, et al. A genetic basis of variation in eccrine sweat gland and hair follicle density. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(32):9932–9937. doi:10.1073/pnas.1511680112

- Kaseb H, Babiker HM. Cancer, An Overview of Eccrine Carcinoma. [Updated 2019 May 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541042/

- Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, Ghazarian D. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011 Sep;64(9):788-92.

- Larson K, Babiker HM, Kovoor A, Liau J, Eldersveld J, Elquza E. Oral Capecitabine Achieves Response in Metastatic Eccrine Carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2018;2018:7127048.

- Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, Salvadori A, Anichini C, Giannini A. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2001 Apr;125(4):498-505.

- Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, Wick MR. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1987 Apr;14(2):65-86.

- Ohnishi T, Kaneko S, Egi M, Takizawa H, Watanabe S. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: report of a case with immunohistochemical analysis of cytokeratin expression. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002 Oct;24(5):409-13.

- Abedi SM, Yu R, Salama S, Alowami S. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma. Cutis. 2015 Sep;96(3):162,191-2.

- Hemalatha, AL, Kausalya, SK,, Amita, K, Sanjay, M, Lavanya, MS. Primary mucinous eccrine adenocarcinoma - a rare malignant cutaneous adnexal neoplasm at an unconventional site. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(8):FD14–FD15. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/9797.4754

- ↑ Cazzato, G., et al., Endocrine Mucin-Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma: Case Presentation with a Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Dermatopathology (Basel), 2023. 10(3): p. 266-280.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Wittmer, A., et al., Endocrine Mucin Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma Treated With Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 2025. 24(5): p. 498-501.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Froehlich, M.H., et al., Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat, 2022. 33(4): p. 2182-2191.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Brett, M.A., et al., Endocrine Mucin-Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma, a Histological Challenge. Case Rep Pathol, 2017. 2017: p. 6343709.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 LeBlanc Endocrine mucin producing sweat gland carcinoma. 2025.

- ↑ A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2017. 76(6): p. AB4.

- ↑ Flieder, A., et al., Endocrine Mucin-Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma: A Cutaneous Neoplasm Analogous to Solid Papillary Carcinoma of Breast. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 1997. 21(12): p. 1501-1506.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Agni, M., et al., An Update on Endocrine Mucin-producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma: Clinicopathologic Study of 63 Cases and Comparative Analysis. Am J Surg Pathol, 2020. 44(8): p. 1005-1016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Au, R.T.M. and M.M. Bundele, Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and associated primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: Review of the literature. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology, 2021. 48(9): p. 1156-1165.

- ↑ Bhanvadia, V.M., et al., Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the eyelid – A diagnostic challenge. Indian Journal of Pathology and Microbiology, 2024. 67(2): p. 456-458.

- ↑ Zhang, L., S. Ge, and X. Fan, A brief review of different types of sweat-gland carcinomas in the eyelid and orbit. Onco Targets Ther, 2013. 6: p. 331-40.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Feng, Y., C.A. Chiou, and N. Wolkow, Cystic-Appearing Eyelid Lesion in a 62-Year-Old Man. JAMA Ophthalmology, 2024. 142(3): p. 266-267.

- ↑ Tzoumpa, S., et al., Unresectable endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma revealing an actionable somatic CHEK2 gene mutation. EJC Skin Cancer, 2024. 2.