Electrical and Lightning-Induced Ocular Trauma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Electrical trauma has become an increasingly recognized problem in modern society, where reliance on electricity is part of daily life. Electrical injuries account for approximately 4-5 % of all U.S. burn-center admissions; they cause about 1000 deaths annually of which about 400 involve high voltage electricity and 50-300 are due to lightning.[1][2] Nonfatal electrical shocks are far more common, with at least 30,000 incidents reported each year.[2] Children represent about 20% of all cases, with the greatest risk seen in toddlers from low-voltage household sources and adolescents from outdoor high-voltage contact.[2] Among adults, electrical injuries occur most often in occupational settings, making them the fourth leading cause of traumatic work-related death. In children, however, injuries usually take place in the home.[3]

Although ocular involvement is relatively uncommon compared with cutaneous or neurologic injury, electrical and lightning-related trauma can cause significant visual morbidity. The eye’s unique conductive and pigmented tissues make it especially vulnerable to current-induced damage. This article reviews the epidemiology, pathophysiology, ocular manifestations, diagnostic evaluation, and management of electrical and lightning-induced eye injuries.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Electrical injuries are classified as:

- High-voltage: ≥ 1,000 volts (V)

- Low-voltage: <1,000 V[1]

Injuries result from direct exposure to electrical current from artificial sources such as household wiring, electrical outlets, appliances, industrial equipment, and overhead power lines as well as natural sources such as lightning.

Pediatric Risk Factors

- High-voltage injuries:

- Most commonly affect adolescents aged 13-18 years old.

- Typically occur in outdoor residential settings. Common scenarios include accidental contact with power lines near rooftops or balconies.[4]

- Low-voltage injuries:

- Predominantly affect children younger than 5 years.

- Usually occur indoors, with common causes including unsafe electrical cords, defective devices, and insertion of objects into electrical outlets.[4]

Adult and Occupational Risk Factors

- Most adult electrical injuries occur in occupational settings. High-risk occupations include electricians, construction workers, and individuals exposed to high voltage equipment.

- More than 50% of fatal occupational electrocutions involve overhead power lines.

- Approximately 25% involve energized machinery or hand tools.[5] [6]

Lightning-Related Injury

Lightning injuries occur through transfer of electrical energy via:

- Direct strike

- Contact with an object that has been struck

- Side splash from a nearby object

- Ground current propagation from the strike point

Lightning delivers extremely high electrical energy, often exceeding 100,000,000 V. Severe injury may occur even without direct contact.[7]

Mechanisms and Pathophysiology

The severity of electrical injury depends on the properties of the current and the tissues it traverses. Factors such as voltage, current strength, type (alternating vs direct), tissue resistance, duration of contact, and individual susceptibility all influence the outcome. According to Ohm’s law, current flow (I) is proportional to voltage and inversely related to resistance (R); I = V/R.[1]

Current Type

Electrical current may be:

- Alternating currents (AC), which changes direction rhythmically and are commonly see in household outlets. Low-frequency AC may prevent voluntary release from the electrical source, prolonging exposure and increasing injury severity.[2]

- Direct currents (DC), which flows in a single direction and are delivered by batteries and medical devices such as defibrillators.

Higher voltage and current are associated with greater tissue damage, regardless of current type.[8][9]

Voltage-Dependent Ocular Injury

High-voltage exposure is associated with increased frequency and severity of ocular injury, including cataract, superficial punctate keratitis, chemosis, ocular hypertension, lens dislocation, retinal and optic-nerve atrophy, and macular edema.[10] For instance, eyelid burns and conjunctival chemosis were found to occur at mean voltages of 10.7 kV and 17.6 kV, whereas vision-threatening injuries such as optic neuropathy and retinopathy occurred at approximately 38.4 kV and 35.5 kV respectively.[11] These findings highlight voltage-dependent gradients of ocular damage and the need for comprehensive eye evaluation and long-term follow-up after any high-voltage or craniofacial electrical insult.

Tissue Resistance and Energy Deposition

- Low-resistance tissues such as blood vessels, nerves, and ocular media conduct electricity efficiently and experience less surface heating.

- High-resistance tissues such as bone, fat, and dry skin dissipate more energy as heat, producing local burns.[12][13]

- The cornea, aqueous, vitreous humor, as well as the neural and vascular tissues are low-resistance pathways, however, localized resistance generates heat that can damage delicate structures. In the lens, this process causes protein denaturation and aggregation, leading to cataract formation (typically posterior and anterior subcapsular). Pigmented tissues such as the iris and retinal pigment epithelium are particularly vulnerable due to melanin-mediated energy absorption, leading to thermal injury and coagulative necrosis. Retinal thermal damage may cause peripapillary opacification that can later progress to atrophy, even without direct vascular injury.[14][15]

Primary Prevention

Most electrical injuries are preventable through basic safety measures at work and in daily life, including regular inspection and replacement of damaged cords or equipment, keeping electrical devices away from water, and following manufacturer instructions.[10]

Lightning injuries can also be largely avoided with awareness and prompt action. Outdoor activities should stop as soon as thunder is heard, with a 30-minute wait after the last thunder before resuming. Safe shelter includes fully enclosed buildings or vehicles, while exposed locations such as ridges, towers, tents, open shelters, or isolated trees should be avoided. If no shelter is available, individuals should crouch low on a dry, non-conductive surface, spread out in groups, and exercise extra caution near water or in mountainous areas, avoiding metal objects and conductive equipment.[7]

Ocular Manifestations

Anterior Segment

Electrical and lightning injuries to the eye, while rare, can affect both the anterior and posterior segments. Complications may occur immediately or develop over weeks to months, even after an initially normal exam. Reported anterior segment findings include: cataracts, keratitis, anterior uveitis, corneal edema, conjunctivitis, and chemosis.

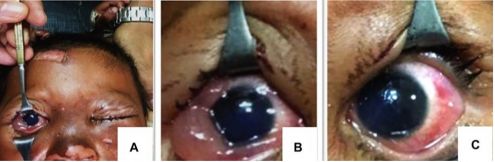

Case 1

- Presentation: A 26-month-old girl was evaluated 3 days after a lightning strike that caused first-degree facial burns. She was able to track a torchlight, and gross visual function was normal (Figure 1a).

- Anterior Segment Findings: Ultrasonography was normal, although bilateral corneal haze, corneal edema, conjunctival chemosis, (Figures 1b and 1c), and cataracts were noted.

- Management and outcome: The child was treated with topical antibiotics (tobramycin), cycloplegics (cyclopentolate 1%), and corticosteroids (prednisolone 1%), which improved the corneal and conjunctival findings. Anterior vitrectomy with intraocular lens implantation was performed to reduce amblyopia risk.[16]

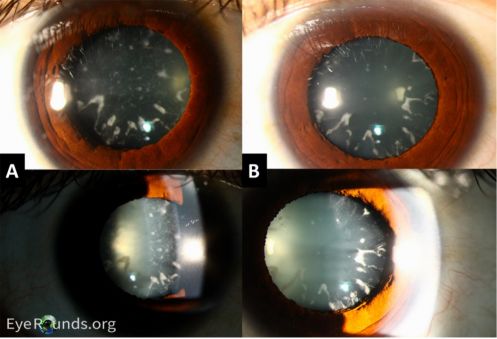

Case 2

- Presentation: A 32-year-old man developed blurred vision in the right eye approximately three months after electrocution from a severed wire.

- Anterior Segment Findings: Slit-lamp exam showed bilateral circumferential anterior cortical cataracts, right-sided 3–4+ posterior subcapsular cataract, and a right-sided dulled red reflex (Figures 2a and 2b).

- Management and outcome: The patient underwent bilateral phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation. Four months after surgery, visual acuity improved to from 20/100 to 20/25 in the right eye and from 20/50 to 20/20 in the left eye.[17] The delayed presentation of cataracts in this patient reminds us that clinicians should follow-up with patients in a timely manner to evaluate whether there are new ocular complications such that patients can receive timely treatment.

Posterior Segment

In the posterior segment of the eye, macular cysts and holes are among the most frequently reported complications following electrical injury, although they often occur alongside other anterior and posterior segment pathologies. These lesions may coexist with other ocular findings and, in some cases, resolve spontaneously.

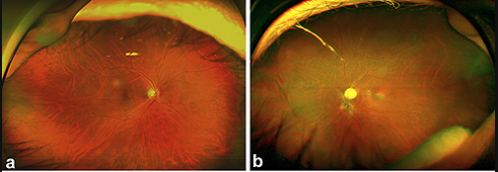

Case 1

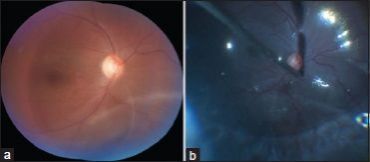

- Presentation: A 43-year-old electrical engineer sustained a 22,000-volt electric shock and experienced bilateral decreased vision along with severe burns in his left arm.

- Posterior Segment Findings: At 3 months, right eye fundus examination was normal (Figure 3a), however, spectral-domain OCT revealed an impending macular hole with thinning of the inner retinal layers. Follow-up OCT at five months showed partial reduction of the defect, and at 18 months, there was restoration of ellipsoid-zone integrity. Fundus of the left eye demonstrated a pigmented fibrotic lesion inferior to the optic disc, generalized vessel attenuation, and mid-peripheral retinal pigment epithelium atrophy (Figure 3b). OCT documented outer retinal disruption and diffuse retinal atrophy, aligning with hypo-autofluorescence found on fundus autofluorescence.

- Management and outcome: Both eyes were observed with close follow-up. Best-corrected visual acuity improved from 20/40 to 20/32 in the right eye. Vision in the left eye remained limited to hand motion due to irreversible atrophic changes.[18] This case highlights that macular damage after electrical injury can be asymmetric between eyes, which may warrant varying degrees of observation.

Case 2

Presentation: A 32-year-old man was electrocuted by a severed electrical wire, resulting in bilateral periocular burns.

Posterior Segment Findings: Spectral-domain OCT demonstrated a full-thickness macular hole.

Management and outcome: The patient was referred for vitreoretinal evaluation but was lost to follow-up, however, 6 months later, imaging showed complete spontaneous closure of the hole.[18][19] Since it appears that macular holes may undergo gradual spontaneous recovery, observation and timely follow-up appointments with patients may be recommended before exploring invasive surgical options.

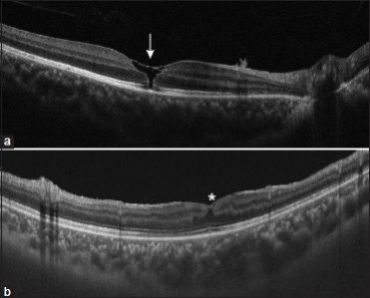

Case 3

Presentation: A 16-year-old boy presented one month after a lightning strike with decreased vision, redness, and pain in his right eye. Visual acuity was 6/36 in the right eye and 6/6 in the left.

Posterior Segment Findings: OCT of the right eye demonstrated a full-thickness macular hole with partial vitreous detachment (Figure 4a). Over the following weeks, multiple small, sieve-like peripheral breaks developed, progressing to an inferior rhegmatogenous retinal detachment visualized on fundus photograph (Figure 5).

Management and outcome: Given that patient also had cataracts, he received cataract extraction, intraocular-lens placement, vitrectomy, and peripheral laser photocoagulation along with silicone-oil tamponade for retinal detachment. Postoperatively, the patient developed ocular hypertension, corneal edema, and granulomatous anterior uveitis resembling acute retinal necrosis, which was well-managed with systemic antivirals, corticosteroids, and topical agents. Three months after silicone-oil removal, the retina remained attached and vision of the right eye improved to 6/18 despite OCT showing foveal distortion and loss of the outer retinal layers (Figure 4b).[20]

Case 4

Presentation: A 40-year-old man experienced progressive bilateral vision loss a decade after work-related electrocution, with a visual acuity of 20/400 in the left eye and vision limited to finger counting in the right.

Posterior Segment Findings: Fundus evaluation revealed optic-disc pallor and widespread chorioretinal atrophy extending into the mid-periphery and partially involving the macula. OCT demonstrated extensive thinning of both choroid and retina with outer-retinal attenuation.

Management and outcome: Supportive care was provided, as structural damage was chronic and irreversible.[14] These findings highlight the importance of long-term ocular surveillance after electrical injury, as delayed ocular manifestations can develop even years after exposure.

Overall, posterior-segment injuries from electrical trauma range from reversible macular holes to progressive retinal and choroidal atrophy. High-voltage and craniofacial current paths carry the greatest risk, and multimodal imaging is essential for detecting delayed structural changes and guiding long-term management.

Neuro-Ophthalmic Sequelae

Optic nerve involvement after electrical injury is uncommon and may occur either in isolation or in combination with anterior or posterior segment pathology.

Case Example

Presentation: A 45-year-old man developed peripheral visual-field loss, photopsias, and blurred central vision in the right eye approximately one week after an electrical injury. Examination revealed a marked relative afferent pupillary defect in the right eye, while central visual acuity remained relatively preserved. Visual acuity in the left eye was 20/40.

Imaging Findings: Slit-lamp examination of both eyes was unremarkable, with no evidence of anterior segment inflammation or injury. Funduscopic examination of the right eye demonstrated diffuse optic-disc edema without associated hemorrhages, exudates, or vascular abnormalities, while the left eye was entirely normal. OCT of the retinal nerve-fiber layer demonstrated thickening of the superior and inferior temporal quadrants in the right eye, consistent with optic nerve edema.

Management and Outcome: The patient was treated with intravenous methylprednisolone. Two weeks later, visual acuity measured 20/40 in both eyes, although a relative afferent pupillary defect and optic-disc swelling persisted in the right eye. At five-month follow-up, the right optic disc appeared pale, and OCT demonstrated generalized thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer, indicating optic atrophy. Central visual acuity improved to nearly 20/20; however, severe peripheral visual-field loss remained.[21]

This pattern of optic-nerve involvement may reflect direct electric conduction injury, secondary ischemic damage, or a mixture of mechanisms, resulting in axonal loss or demyelination. Compared with demyelinating optic neuritis, electric-injury–associated optic neuropathy typically has onset closely following the insult, often lacks pain with eye movement, and may show asymmetric or sectoral disc swelling evolving to pallor and field constriction. Because evidence is limited and causality in many reports is not definitively established, prognosis is variable, and management (including corticosteroid use) must be individualized.

Diagnostic Evaluation

History and Clinical Presentation

- While no formal guidelines exist for ocular evaluation after electrical injury, a detailed exposure history is essential to determine the mechanism, voltage, and timing of injury.

- Recommended assessment as seen in reported cases includes slit-lamp examination, dilated fundus examination, and optical coherence tomography.[10][14][16][22]

- Blurred vision is the most common presenting symptom. Other symptoms generally reflect the ocular structures involved. For instance, in patients with cataracts, they may report cloudiness or haziness in their vision. In the acute phase, involvement of the anterior segment or cornea can produce redness, discomfort, a foreign-body sensation, tearing, and light sensitivity. On the other hand, injuries that damage the retina may present with loss of central vision, distortions in the visual field, and moving shadows or curtain in the visual field. Clinical testing, like the Watzke-Allen sign, can confirm the defect.[19]

Imaging

Multimodal imaging plays a central role in diagnosis, monitoring progression, and guiding management.

Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography

- Identifies macular holes, intraretinal cysts, outer retinal disruption (including the ellipsoid zone), acute retinal edema, and chronic retinal thinning.[16][20][22]

Fundus Photography

- Visualizes peripheral retinal breaks, the extent of retinal detachment, and retinal pigment epithelium changes.[20]

Fundus Autofluorescence and Fluorescein Angiography

- Maps areas of retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction and atrophy.[14]

Optic Nerve Imaging

- Useful in detecting swelling of the retinal nerve-fiber layer and optic nerve atrophy.[21]

Anterior-Segment Imaging

Laboratory Tests

Although laboratory testing is not specific to ocular trauma, ophthalmologists may occasionally be the first or only specialists to evaluate patients who have sustained electrical injuries and possibly only have ocular complaints. Some individuals may initially recover from the systemic effects of electrocution and later present with only visual complaints or periocular burns. In such cases, it is important for ophthalmologists to recognize that occult cardiac, renal, or metabolic complications such as silent arrhythmias may persist or emerge over time. Ophthalmologists can play a proactive role by recommending timely systemic evaluation through appropriate specialty referrals and ensuring that a complete multidisciplinary assessment is carried out.

Cardiac Evaluation

- All patients with electrical injury should undergo electrocardiogram (ECG) and cardiac monitoring, even if asymptomatic.

- Cardiac biomarkers (troponin, creatine kinase–MB) are indicated when chest pain or angina is reported or when ECG abnormalities are present.

Complete Blood Count (CBC)

- Evaluates anemia that may occur secondary to burns

- Detects leukocytosis from stress or infection (loss of protective skin barrier)

Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP)

- Assesses electrolyte disturbances (hyperkalemia and hypocalcemia) and evaluates renal function

Urinalysis

- Evaluates presence of myoglobinuria and creatine kinase (CK) levels to determine if there is muscle injury and rhabdomyolysis

Arterial Blood Gas Analysis

- Consider if respiratory compromise is suspected

- Baseline measurement of electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine informs fluid resuscitation, correction of metabolic abnormalities, and strategies to protect renal function.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

A documented history of electrical shock or lightning exposure is the most important clue in diagnosing electrical trauma. Rapidly developing cataracts, often bilateral, are a hallmark finding. Macular cysts or macular holes are commonly present and are frequently accompanied by retinal pigment epithelium changes. Less commonly, patients develop rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, posterior vitreous detachment, or optic neuropathy associated with peripheral-field constriction, photopsia, and blurred central vision. Electroretinogram and electrooculogram testing may show reduced amplitudes, reflecting retinal dysfunction related to electrical injury. This constellation of findings is uncommon in other forms of ocular trauma or disease.[10][16][24]

Contrast this with:

- Blunt ocular trauma, which commonly presents with hyphema, orbital fractures, open-globe injuries, and unilateral cataracts that develop over a longer period[25]

- Age-related cataracts, which occur in older patients and progresses gradually over time.[26]

- Demyelinating optic neuritis, which presents with painful eye movements, central scotomas, dyschromatopsia, and optic-nerve enhancement on MRI.

- Ischemic optic neuropathy, which occurs in older patients with vascular risk factors and produces altitudinal visual-field defects. Disc edema with peripapillary hemorrhages may be present, a feature that electrical-induced optic neuropathy lacks.[27]

Management

General and Emergency Care

Initial management of electrical-injury patients primarily involves systemic stabilization by emergency or burn specialists. Although ocular trauma alone rarely necessitates interventions such as airway support or cardiac monitoring, patients with periocular burns or visual complaints may present as part of a broader multisystem injury. Ophthalmologists should ensure coordination with emergency and critical-care teams while focusing on ocular evaluation once systemic stability has been achieved.[2]

General ophthalmic care may involve:

- Protecting the cornea with preservative-free lubricants, moisture chambers, or temporary tarsorrhaphy if eyelid closure is incomplete[28][29]

- Irrigating the eye if foreign bodies or debris are present

- Applying antibiotic ointments and lubricants for superficial burns and performing eschar debridement, contracture release, and eyelid resurfacing with skin grafts for deeper burns[30]

- Long-term follow-up of multimodal imaging given that ocular complications may arise years after the injury[10][14]

- In a 10-year case series of deep periorbital burns, initial ocular hygiene (irrigation), frequent lubrication, and early surgical planning were associated with reduced late ocular morbidity.[31]

Medical Therapy

Corticosteroids are sometimes used in the management of electrical ocular injuries, particularly when optic-nerve involvement or significant intraocular inflammation is present. Their efficacy, however, remains uncertain, and evidence is primarily limited to case reports:

- A 23-year-old man with a high-voltage electrical burn who developed anterior and intermediate uveitis in the right eye presented with conjunctival redness, corneal edema, and a clear lens. Treatment with topical prednisolone 1% and intravenous dexamethasone led to rapid improvement: visual acuity increased from 6/120 to 6/15 within four days and to 6/9 by four weeks, with resolution of anterior chamber inflammation.[32]

- Similarly, a 19-year-old man with post-electrical iritis in the left eye achieved full resolution of inflammation and restoration of vision from 20/30 to 20/20 over two months with topical steroid therapy alone.[33]

Despite these positive case outcomes, randomized trials and systematic reviews have not demonstrated a clear benefit of corticosteroids for traumatic optic neuropathy compared with observation. The optimal approach to managing ocular trauma from electrical injuries remains undefined, and further research is needed to establish evidence-based treatment guidelines.[10]

Surgical Management

Phacoemulsification and pars plana vitrectomy are the most commonly employed surgical interventions for patients with electricity-induced ocular injuries. While large-scale studies specific to electrical trauma are lacking, outcomes can be extrapolated from other types of ocular trauma. Cataract extraction, often combined with intraocular lens implantation, has been shown to improve vision in approximately 90% of patients with trauma-related cataracts, with 86% achieving final visual acuity between 6/6 and 6/18. Pars plana vitrectomy is frequently performed for serious posterior-segment injuries, such as macular holes or vitreous pathology, and results in visual improvement in roughly two-thirds of patients following severe ocular trauma.[10]

Two electrical trauma-specific cases support these findings: a 26-month-old girl achieved marked visual recovery after vitrectomy with lens implantation,[16] and a 32-year-old man experienced significant visual improvement following bilateral phacoemulsification with intraocular lens placement.[19] Together, these data highlight that surgical intervention can meaningfully restore vision in patients with electricity-induced ocular injuries.

Prognosis

Visual prognosis following electrical or lightning-induced ocular trauma varies widely and depends on several key factors, including voltage, current pathway, duration of exposure, and the specific ocular structures involved.[10][15]Injuries limited to the anterior segment such as superficial keratitis or early lens opacities often recover well with prompt medical or surgical management. In contrast, posterior-segment and neuro-ophthalmic complications, including macular holes, retinal detachment, and optic neuropathy, are more likely to result in lasting visual impairment despite appropriate treatment.[21][22][23]

A distinguishing feature of electrical injury is its potential for delayed visual decline, sometimes occurring months or even years after the initial trauma.[15] Progressive retinal pigment-epithelium and choroidal atrophy, optic-nerve pallor, and secondary glaucoma have all been reported long after initial recovery. This underscores the importance of lifelong ophthalmic surveillance, particularly in patients exposed to high-voltage current or with documented posterior-segment involvement.

Overall, patients with localized anterior-segment disease can achieve excellent outcomes, while those with macular or optic-nerve injury often experience partial or incomplete visual recovery. Advances in multimodal imaging and timely surgical intervention have improved anatomical outcomes in recent years, but the long-term prognosis remains guarded in severe cases. Continued follow-up allows early detection of delayed sequelae and offers the best opportunity for visual preservation.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Sanford A, Gamelli RL. Chapter 65 - Lightning and thermal injuries. In: Biller J, Ferro JM, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol 120. Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part II. Elsevier; 2014:981-986. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-4087-0.00065-6

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Zemaitis MR, Guirguis M, Cindass R. Electrical Injuries. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed September 20, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448087/

- ↑ Karray R, Chakroun-Walha O, Mechri F, et al. Outcomes of electrical injuries in the emergency department: epidemiology, severity predictors, and chronic sequelae. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2025;51(1):85. doi:10.1007/s00068-025-02766-1

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gurbuz K, Demir M. Patterns and Outcomes of High-Voltage vs Low-Voltage Pediatric Electrical Injuries: An 8-Year Retrospective Analysis of a Tertiary-Level Burn Center. J Burn Care Res. 2022;43(3):704-709. doi:10.1093/jbcr/irab178

- ↑ Salehi SH, Sadat Azad Y, Bagheri T, et al. Epidemiology of Occupational Electrical Injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2022;43(2):399-402. doi:10.1093/jbcr/irab171

- ↑ Khor D, AlQasas T, Galet C, et al. Electrical injuries and outcomes: A retrospective review. Burns. 2023;49(7):1739-1744. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2023.03.015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Davis C, Engeln A, Johnson EL, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Lightning Injuries: 2014 Update. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 2014;25(4_suppl):S86-S95. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2014.08.011

- ↑ Dechent D, Emonds T, Stunder D, Schmiedchen K, Kraus T, Driessen S. Direct current electrical injuries: A systematic review of case reports and case series. Burns. 2020;46(2):267-278. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2018.11.020

- ↑ Electrical Injuries - Injuries; Poisoning. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Accessed September 20, 2025. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/electrical-and-lightning-injuries/electrical-injuries

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Piedrahita MA, Pineda-Vanegas AF, Moreno-Mendoza F, et al. Ophthalmological manifestations, visual outcomes, and treatment of electrical and lightning trauma: A Systematic Review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Published online June 27, 2025. doi:10.1007/s00417-025-06844-3

- ↑ Abu Serhan H, Taha MJJ, Abuawwad MT, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations and complications following electrical injury: A comprehensive systematic review. AJO International. 2025;2(1):100089. doi:10.1016/j.ajoint.2024.100089

- ↑ Miranda-de la Lama GC. Electro-thermal injuries in ruminants caused by electrical equipment during pre-slaughter operations: Forensic case reports from an animal welfare science perspective. Forensic Science International. 2024;356:111936. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2024.111936

- ↑ Fish RM, Geddes LA. Conduction of Electrical Current to and Through the Human Body: A Review. Eplasty. 2009;9:e44.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Valera-Cornejo DA, García-Roa M, Ramírez-Neria P, Romero-Morales V, Villalpando-Gómez Y, García-Franco R. Electric Shock Retinopathy: Case Report of a Late Retinal Manifestation. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2020;4(2):139-143. doi:10.1177/2474126420903277

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Tandon M, Agarwal A, Gupta V, Gupta A. Peripapillary retinal thermal coagulation following electrical injury. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(5):240-242. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.109532

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Pradhan E, Khatri A, Ahmed AA, et al. Lightning Injury to Eye: Brief Review of the Literature and Case Series. OPTH. 2020;Volume 14:597-607. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S242327

- ↑ Electrocution Induced Cataracts and Macular Hole. Accessed September 30, 2025. https://eyerounds.org/cases/357-electrocution-induced-cataract.htm#gsc.tab=0

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Choe HR, Park UC. Different Types of Maculopathy in Eyes after a High-Voltage Electrical Shock Injury. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2019;10(1):19-23. doi:10.1159/000496196

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Electrocution Induced Cataracts and Macular Hole. Accessed September 20, 2025. https://eyerounds.org/cases/357-electrocution-induced-cataract.htm#gsc.tab=0

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Gaur S, Vidhu V, Singh J, Sen A. Retinal detachment following lightning injury mimicking acute retinal necrosis: A case report. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology - Case Reports. 2023;3(4):1139. doi:10.4103/IJO.IJO_1144_23

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Izzy S, Deeb W, Peters GB, Mitchell A. Isolated optic nerve oedema as unusual presentation of electric injury. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014205016. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-205016

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Khadka S, Byanju R, Pradhan S, Poon S, Suwal R. Evolution of Lightning Maculopathy: Presentation of Two Clinical Cases and Brief Review of the Literature. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2021;2021:8831987. doi:10.1155/2021/8831987

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Korkmaz A, Karti O, Zengin MO, Sagban LL, Kusbeci T. Simultaneous Cataract, Maculopathy and Optic Atrophy Secondary to High-Voltage Electrical Shock Injury. Neuroophthalmology. 2018;44(1):34-37. doi:10.1080/01658107.2018.1540644

- ↑ Lin CJ, Yang CH, Yang CM, Chang KP. Abnormal electroretinogram and abnormal electrooculogram after lightning-induced ocular injury. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(4):578-579. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01400-3

- ↑ Kwon J woo, Choi MY, Bae JM. Incidence and seasonality of major ocular trauma: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10020. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67315-9

- ↑ Miller KM, Oetting TA, Tweeten JP, et al. Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(1):P1-P126. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.10.006

- ↑ Raizada K, Margolin E. Non-Arteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed September 20, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559045/

- ↑ Patek GC, Bates A, Zanaboni A. Ocular Burns. Nih.gov. Published June 26, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459221/#

- ↑ Reed DS, Plaster AL, Mehta A, et al. Acute And Sub-Acute Reconstruction Of Periorbital Thermal Burns Involving The Anterior Lamella Of The Eyelid With Simultaneous Fullthickness Skin Grafting And Amniotic Membrane Grafting. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2020;33(4):323-328.

- ↑ Sarabahi S, Kanchana K. Management of ocular and periocular burns. Indian Journal of Burns. 2014;22(1):22. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-653x.146997

- ↑ Kalinova K, Raycheva R, Petrova N, Uchikov P. Acute Management of Deep Periorbital Burns: A 10-Year Review of Experience. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2024;37(1):53-63. Published 2024 Mar 31.

- ↑ Pineda-Vanegas AF, Moreno-Mendoza F, Estévez-Flórez MA, et al. Anterior and intermediate uveitis with macular hole probably secondary to high-voltage electrical burn. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2025;108(2):220-222. doi:10.1080/08164622.2024.2364761

- ↑ Sharma A, Reddy YVG, Shetty AP, Kader SMA. Electric shock induced Purtscher-like retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(9):1497-1500. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1737_18