Eyelid Burns

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

General Pathology

Burns may be caused by thermal, chemical or electrical sources which can all be both life threatening and sight threatening. Thermal burns are the most common, often affecting the eyelids, the periocularregion & the face. Ophthalmic involvement occurs between 7.5% and 27% of patients admitted to burn units. However, the loss of an eye and/or vision after a thermal injury is uncommon, primarily due to a significant number of inherent protective mechanisms such as the blink reflex, Bell's phenomenon, and protective movements of the arm to cover the face and protect it from the source of the burn.

In severe periocular burns, massive edema and large-volume fluid resuscitation (as is needed for burns > 20% total body surface area (TBSA) can precipitate orbital compartment syndrome (OCS). Early ophthalmology consultation, involvement and serial IOP checks during the first 24–48 hours is recommended. [1][2]

The most common mechanisms of thermal burn injuries are fire/flame (46%) and scald (32%), with scald burns being particularly problematic in children, who have thinner epithelium and dermis. Of those admitted to burn units, eyelid burns were more common than other burn/injury to the eye(s). While chemical burns, whether accidental and intentional, can also inflict serious harm , the focus of this article will be on thermal burns.[3][4]

Pathophysiology

Burn injury results in the release of multiple inflammatory mediators that result in vasodilatation, pain, and edema. Within the rigid orbital compartment, this surrounding and overlying acute edema may sharply increase intraorbital pressure. When perfusion pressure is exceeded, OCS ensues, risking ischemic optic neuropathy and retinal ischemia. [2][5]

The depth of burn depends on the intensity of heat exposure, the duration of exposure, and the thickness of epidermis and dermis. Eyelid skin is thinnest in the body and there is a lack of subcutaneous fat, leading to deeper burns compared to skin elsewhere receiving a similar exposure.

The three zones of a burn were described by Jackson in 1947.

Zone of coagulation

This zone encompasses the point of maximum damage. In this zone there is irreversible tissue loss due to coagulation of the constituent proteins.

Zone of stasis

The surrounding zone of stasis is characterized by decreased tissue perfusion. The tissue in this zone is potentially salvageable. Thus the main goal of burn resuscitation is to increase tissue perfusion and minimize irreversible damage. Additional insults, such as prolonged hypotension, infection, or edema, can convert this zone into an area of complete tissue loss.

Zone of hyperemia

In this outermost zone tissue perfusion is increased. The tissue here will invariably recover unless there is severe sepsis or prolonged hypoperfusion.[6]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is clinically obvious, especially when combined with a typical and reliable history. Occasionally, the exact mechanism of injury (hot water, chemical(s), fire, contact thermal burn etc.) may be unknown, making it difficult to predict how a burn may evolve. For example, a burn may appear partial thickness but convert to a full thickness burn due to the mechanism being burn from grease (or other factors, such as age, co-morbidities or inadequate resuscitation). Eyelid burns are classified based on their depth and how much they penetrate the skin's surface.

Classification

Ocular adnexal burns may be classified depending on the extent, depth and severity of the injury including underlying tissue damage.

First degree burns / Epidermal burns

This corresponds to the zone of hyperemia in Jackson’s model. Severe sunburn is the most common example of first-degree burn. A severe sunburn is the most common example of first-degree burn. By definition, only the epidermis is affected, and there is no blistering . Patients feel pain due to local vasodilator prostaglandins, and healing is usually complete within a week. [3]

Second degree burns / Partial-thickness burns

Partial-thickness burns involve the dermis and epidermis. This corresponds to the zone of stasis in Jackson’s model. It is commonly divided into superficial and deep dermal injury.

Superficial Partial-Thickness Burns

Injury to the epidermis and superficial papillary dermis results in thin-walled, fluid-filled blisters with a moist red base. The exposure of superficial nerves makes these injuries painful. A burn of this depth usually heals within two to three weeks by regeneration of epidermis from keratinocytes within sweat glands and hair follicles, with minimal scarring, contracture and low risk of infection.

Deep Partial Thickness Burns

These burns have a pale white or mottled base beneath the blisters. The healing takes three or more weeks, and is accompanied by scarring and contraction. These injuries are of concern in the eyelid region, often necessitating early surgery for contraction and eyelid retraction.[3][7][8] Deep, partial thickness eyelid injuries that will not re-epithelialize by three weeks should be considered for excision and grafting to reduce hypertrophic scarring and contraction. This timing aligns with general burn guidance that deep dermal burns failing to heal within three weeks benefit from early excision and grafting to improve function and appearance. [9]

Third degree burns / Full-thickness burns

In these burns, the epidermis, dermis, and all regenerative elements are destroyed. Third degree burns correspond to the zone of coagulation in Jackson’s burn wound model. The skin is dry, leathery and, as a result of heat coagulation of dermal blood vessels, the affected tissue is avascular and white. Such burns are typically insensate and painless to touch due to destruction of cutaneous nerves in the involved area. Healing only occurs from the edges, takes a prolonged time and is associated with significant contraction. Early excision of affected tissue and skin grafting is the standard of care to promote healing, create closed wounds, decrease fluid losses, decrease pain, decrease risk of infection and eventually decrease metabolic needs (once healing has occurred). Third degree eyelid burns should undergo early surgery to resurface the burnt area and prevent secondary severe corneal complications from exposure and secondary infection.[10][11][12]

For eyelid resurfacing, full thickness autograft skin is generally preferred over split thickness grafts because it contracts less and lowers the risk of ectropion. In a series of acute eyelid burns, ectropion developed in 30 percent of patients after full thickness grafting compared with 88 percent after split thickness grafting. [13]

Fourth degree burns / Deep burns

These are full thickness burns with destruction of the underlying fat (fourth degree), muscle (fifth degree) and bone (sixth degree). Such burns require extensive and complex multidisciplinary management and often result in severe contracture and prolonged disability. [14]

Based on these definitions and the likelihood of surgery, eyelid burns may be classified as mild, moderate, or major. Mild or minimal burns describe superficial partial-thickness burns that usually heal without the need for surgery. Moderate burns refer to deeper partial-thickness burns that are delayed in healing but may not require surgery. Major eyelid burns are deep-partial or full-thickness and invariably require early surgery with skin grafts.[3]

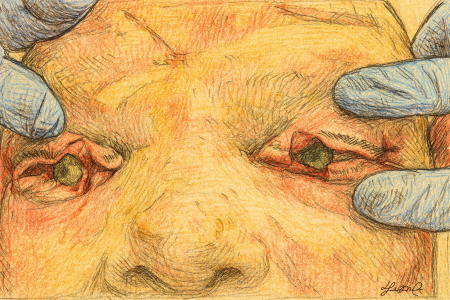

Physical Examination

Patients with facial burns should be seen by an ophthalmologist as soon as possible to assess the extent of eyelid, eyelid margin and ocular surface injury. Ocular surface examination should include not only the cornea, but also the bulbar, forniceal and tarsal conjunctiva. The presence of particulate material and foreign bodies on the ocular surface should be carefully assessed, and when intraocular or intraorbital involvement is suspected—particularly in the context of high-velocity trauma or blast injuries—further evaluation with appropriate imaging is warranted to exclude deeper penetration. The presence of a contact lens should not be overlooked. This assessment should be made, if possible, in the emergency room if necessary under topical anesthetic (after ruling out open globe injury) before significant conjunctival and eyelid edema prevents a thorough exam.

High‑risk burn patients (large TBSA, periorbital burns, or high resuscitation volumes) should be screened for OCS. Concerning findings include rock‑hard eyelids, proptosis, decreased vision or RAPD, ophthalmoplegia, and markedly elevated IOP, often >35–40 mmHg. [2][5]

The most critical issue for the ophthalmologist is the integrity of the corneal surface. Therefore, a proper corneal evaluation should be performed using fluorescein strips and a cobalt blue light in the emergency room or burn unit. Even with no initial corneal damage, sequelae from eyelid retraction can occur later and monitoring is mandatory.

The depth and extent of burns in the eyelid and facial area should be initially assessed, and documented with photography if possible. In the presence of a partial-thickness burn, eyelid contracture producing progressive lagophthalmos and corneal exposure is likely. Therefore, the presence or absence of a Bell’s phenomenon should be documented.[3][15] Early discussion with burn and oculoplastic teams should establish a plan for wound coverage and eyelid position, including the likely need for grafting if healing will be delayed. Temporary coverage options such as cadaveric skin allograft or a synthetic dermal matrix like a biodegradable temporizing matrix can protect the wound bed until definitive autograft is performed or when donor sites are limited in a large TBSA burn and need to heal prior to re-harvesting. [16][17]However, in the latter situation, eyelid reconstruction should be prioritized.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) monitoring may be important in the patient who receives intravenous fluid resuscitation, as elevation may occur within 72 hours of large shifts from the intravascular compartment to the extravascular compartment. Consider scheduled IOP checks in the first 48–72 hours for patients with >5–6 cc/kg/%TBSA resuscitation or resuscitation above the Ivy Index (≥250 mL/kg), as these thresholds correlate with increased OCS risk. Intervene urgently for IOP >30–40 mmHg with compatible ischemic signs.[1] [2][18][19] Third spacing of intravascular volume peaks at 6-12 hours and increases with aggressive fluid resuscitation. Positive pressure ventilation can also exacerbate the edema and potential lagophthalmos.[3][20][21]

Management

Immediate priorities following burns including assessment of the extent of the burns and presence of orofacial involvement. Securing the airway, skin protection, hydration and antibiotics (topical antibiotics preferred, and systemic antibiotics if patient is septic) are essential.

Ophthalmic management following assessment includes adequate lubricating antibiotic eyedrops and ointments, moisture chambers, and frequent evaluation of both the globes and the eyelids.

- When deep eyelid burns are present, early coordination with the burn or plastic surgery service can facilitate timely excision and appropriate graft selection. If immediate autografting is not possible because of donor scarcity or wound bed status, short term coverage with cadaveric allograft or application of a dermal substitute (such as a biodegradable temporizing matrix) can maintain a protected surface and prepare the bed for an autograft that restores eyelid mobility. [16][22]

- All efforts to minimize scarring of the ocular surface and periocular area should be taken. Once cicatricial changes begin in the eyelids and ocular surface, a relentless and rapid deterioration often ensues with secondary cicatricial eyelid retraction, ectropion, lagophthalmos, and corneal exposure.

- Chemical injuries should be treated based on the extent of injury after the ocular surface pH is normalized post-irrigation, details on chemical injuries can be seen under that topic. In the acute setting, head elevation may be helpful in preventing further swelling around the eyelids. If OCS is suspected, do not delay for imaging. Perform emergent lateral canthotomy with inferior cantholysis. Add superior cantholysis if pressures remain elevated. Medical therapy is adjunctive and must not delay decompression.[5][23]

Compartment Syndrome and Additional Intervention

If a standard lateral canthotomy with inferior and superior cantholysis fails to adequately reduce intraocular pressure or improve ocular perfusion, further emergent decompressive steps are indicated.[24]

- One option is a transconjunctival inferior fornix incision with inferior orbital septum release to allow prolapse of orbital fat and additional orbital decompression. Cadaveric studies show that an inferior septum release can significantly lower orbital pressure (≈52 mm Hg reduction) and provides additional benefit when performed after canthotomy/cantholysis. [25]

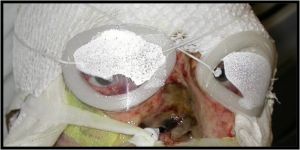

- Another option is a full-thickness eyelid margin incision, a “four-lid blepharotomy” or vertical eyelid split, which involves vertically dividing the lateral aspects of both upper and lower eyelids to open the anterior orbital compartment. This maneuver can relieve orbital pressure when lesser measures are insufficient, though it carries a risk of exposure keratopathy and will require timely eyelid repair in the healing phase. [3][7][15][26][27]

- The third option is an orbital decompression.

General treatment

The principles of wound management for eyelid burns are those for any burn: assessment, cleansing, and protection followed by resurfacing for deeper burns. With an extreme burn injury requiring significant fluid resuscitation, secondary orbtial edema may present as an orbital compartment syndrome (OCS), in such cases a canthotomy, cantholysis & septolysis may be necessary to control the IOP and prevent permanent visual loss.

Lubrication

- Lubrication within 24 hours of admission, with copious application as required, is particularly important as burn patients often have reduced tear production, blink reflex, and eyelid mobility or excursion.

Wound Care

- Singed or scorched eyelashes are usually present in a thermal eyelid burn and should be removed to avoid the possibility of char falling into the eye and prolonging ocular surface discomfort. Debride necrotic skin as needed.

Wound Bed Preparation and Steps of Reconstruction

- Graft choice for eyelid resurfacing should favor full thickness autograft when possible to limit contraction and lower the chance of ectropion and exposure keratopathy, with split thickness grafts reserved for large area needs or donor constraints. Temporary options include cadaveric allograft, which is generally rejected within two to three weeks, and synthetic dermal matrices such as a biodegradable temporizing matrix that forms a neodermis before thin autograft placement.[13][17][22]

- Cicatricial lagophthalmos can develop early and requires aggressive treatment until skin grafting can be performed.

- In the presence of lagophthalmos with a severe burn of the eyelid skin, clear occlusive dressing with adequate lubricant gels ('cling wrap or Saran Wrap or TegaDerm) is generally useful. Measures than can be used to protect the corneal surface until skin grafting can be performed include amniotic membrane and suture tarsorrhaphy.

- If tissue loss is extensive and donor skin is limited, temporary cadaveric allograft or placement of a dermal substitute can be considered after burn excision to stabilize the wound bed and facilitate later autograft with improved graft take. Comparative head and neck data show no skin graft failures after biodegradable temporizing matrix compared with a 37.5 percent failure rate after collagen chondroitin silicone bilayer templates such as Integra, with similar complication rates. [22]

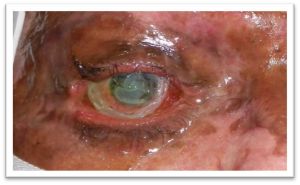

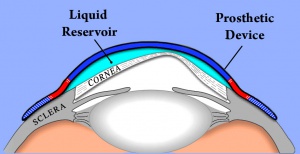

- In cases where amniotic membrane is not available and tarsorrhapy is not feasible due to extensive tissue loss a Boston Ocular Surface Prosthesis can also be use to protect the cornea.[26]

- As extreme injury with secondary orbtial edema may present as an orbital compartment syndrome (OCS), in such cases a canthotomy, cantholysis & septolysis may be necessary to control the IOP and prevent permanent visual loss.

- In the past, skin grafting was usually delayed until the cicatricial changes stabilized, but the early use of full-thickness skin grafts, amniotic membrane, and various types of flaps can effectively reduce ocular morbidity in selected patients.[11][12][28]

- When eyelid resurfacing is performed, full thickness autograft has demonstrated lower rates of ectropion than split thickness graft in the acute burn setting and should be considered the first choice for the eyelid when donor skin allows.[13]

Long term management includes retraction repair with skin grafts, repair of medial canthal deformities, trichiasis, palpebral aperture stenosis, eyebrow deformities, canalicular obstruction, and surgical or laser scar revision.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Echalier, E. L., R. D. Larochelle, J. L. Patnaik, B. R. Echalier, A. Wagner, E. M. Hink, P. S. Subramanian, and S. D. Liao. 2023. 'Orbital Compartment Syndrome in Severe Burns: Predictive Factors, Timing, and Complications of Intervention', Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 39: 341–46.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Makarewicz, N., D. Perrault, P. Cevallos, and C. C. Sheckter. 2024. 'Diagnosis and Management of Orbital Compartment Syndrome in Burn Patients-A Systematic Review', J Burn Care Res, 45: 1367–76.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Raman M., Ijaz S, and Baljit D. The management of Eyelid Burns. Survey of ophthalmology. Volume 54. June 2009

- ↑ Kaplan AT, Yalcin SO, Günaydın NT, Kaymak NZ, Gün RD. Ocular-periocular burns in a tertiary hospital: Epidemiologic characteristics. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023 Jan;76:208-215. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2022.10.049. Epub 2022 Nov 2. PMID: 36527902.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Rixen, Jordan; Verdick, Randall; Allen, Richard C.; Carter, Keith D. 2013. 'Lateral Canthotomy, Inferior Cantholysis.', The University of Iowa, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Accessed August 26. https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/tutorials/lateral-canthotomy-cantholysis.htm.

- ↑ JACKSON DM. [The diagnosis of the depth of burning]. Br J Surg. 1953 May;40(164):588-96. Undetermined Language. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004016413. PMID: 13059343.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Achauer BM, Adair SR. Acute and reconstructive management of the burned eyelid. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;7:87-95

- ↑ Papini R. Management of burn injuries of various depths. BMJ. 2004 Jul 17;329(7458):158-60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7458.158. PMID: 15258073; PMCID: PMC478230.

- ↑ Papini, R. 2004. 'Management of burn injuries of various depths', Bmj, 329: 158–60.

- ↑ Bouchard CS, Morno K, Jeffrey P, et al. Ocular complications of thermal injury: a 3-year retrospective. J Trauma. 2001; 50(1):79-82

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cole JK, Engrav LH, Heimbach DM, et al: Early excision and grafting of face and neck burns in patients over 20 years. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 109: 1266-1273

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fallah LY, Ahmadi A, Ruche AB, Taremiha A, Soltani N, Mafi M. The effect of early change of skin graft dressing on pain and anxiety among burn patients: a two-group randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Burns Trauma. 2019 Feb 15;9(1):13-18. PMID: 30911431; PMCID: PMC6420706.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Lille, S. T., L. H. Engrav, M. T. Caps, J. C. Orcutt, and R. Mann. 1999. 'Full-thickness grafting of acute eyelid burns should not be considered taboo', Plast Reconstr Surg, 104: 637–45.

- ↑ Żwierełło, W., Piorun, K., Skórka-Majewicz, M., Maruszewska, A., Antoniewski, J., & Gutowska, I. 2023. Burns: Classification, Pathophysiology, and Treatment: A Review. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(4), 3749

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Orbit, eyelids, and lacrimal system. (2021). San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Saffle, Jeffrey R. 2009. 'Closure of the excised burn wound: temporary skin substitutes', Clinics in plastic surgery, 36: 627–41.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gupta, Saurabh, Devi P Mohapatra, Ravi K Chittoria, Elankumar Subbarayan, Sireesha K Reddy, Vinayak Chavan, Abhinav Aggarwal, and Likhitha C Reddy. 2019. 'Human skin allograft: Is it a viable option in management of burn patients?', Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery, 12: 132–35.

- ↑ Sullivan, Stephen R, Arash J Ahmadi, Christopher N Singh, Bryan S Sires, Loren H Engrav, Nicole S Gibran, David M Heimbach, and Matthew B Klein. 2006. 'Elevated orbital pressure: another untoward effect of massive resuscitation after burn injury', Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 60: 72–76.

- ↑ Singh, Christopher N, Matthew B Klein, Stephen R Sullivan, Bryan S Sires, Carolyn M Hutter, Kenneth Rice, and Arash Jian-Amadi. 2008. 'Orbital compartment syndrome in burn patients', Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, 24: 102–06.

- ↑ Rachel Dahl, MD, MPH, MS and others, Regional Burn Review: Neither Parkland Nor Brooke Formulas Reach 85% Accuracy Mark for Burn Resuscitation, Journal of Burn Care & Research, 2023;, irad047,

- ↑ Brundridge, WL. Adnexal Burns. Ch 68. In: Servat, JJ et al. eds. Smith and Nesi's Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 4th ed. Springer, 2021: 1223-1230.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Wu, S. S., M. Wells, M. Ascha, R. Duggal, J. Gatherwright, and K. Chepla. 2022. 'Head and Neck Wound Reconstruction Using Biodegradable Temporizing Matrix Versus Collagen-Chondroitin Silicone Bilayer', Eplasty, 22: e31.

- ↑ Su, Desai NM; Shah. 2025. 'Lateral Orbital Canthotomy.' in StatPearls (ed.) (StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL)).

- ↑ Clair, Brandon, James B. Davis, Anna Murchison, Grant A. Justin, Michael T. Yen, Nahyoung Grace Lee, Cat Nguyen Burkat, Amanda D. Henderson, Manpreet Tiwana, and Annie Moreau. 2025. 'Orbital compartment syndrome', American Academy of Ophthalmology, EyeWiki, Accessed June 22. https://eyewiki.org/Orbital_Compartment_Syndrome.

- ↑ Oester, A. E., Jr., B. T. Fowler, and J. C. Fleming. 2012. 'Inferior orbital septum release compared with lateral canthotomy and cantholysis in the management of orbital compartment syndrome', Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 28: 40–3.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Kalwerisky K, Davies B, Mihora L, Czyz CN, Foster JA, DeMartelaere S. Use of the Boston Ocular Surface Prosthesis in the management of severe periorbital thermal injuries: a case series of 10 patients. Ophthalmology. 2012 Mar;119(3):516-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.027. Epub 2011 Nov 30. PMID: 22133791.

- ↑ Dryden, S., R. Gabbard, G. Salloum, A. Meador, J. Laplant, A. Kruglov, B. Fowler, M. Wilson, and J. Fleming. 2024. 'Marginal Full Thickness Blepharotomy for Management of Orbital Compartment Syndrome', Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg, 40: 408–10.

- ↑ Reed DS, Plaster AL, Mehta A, Hill MD, Zanganeh TS, Soeken TA, DeMartelaere SL, Davies BW. Acute And Sub-Acute Reconstruction Of Periorbital Thermal Burns Involving The Anterior Lamella Of The Eyelid With Simultaneous Fullthickness Skin Grafting And Amniotic Membrane Grafting. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2020 Dec 31;33(4):323-328. PMID: 33708023; PMCID: PMC7894844.