History of Retinal Detachment Surgery

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Retinal detachment (RD) has evolved from a largely untreatable condition in the 19th century to a disease with consistently high anatomic success rates in the modern surgical era. Historically, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) was associated with near-certain visual disability, and early medical and surgical interventions offered minimal benefit.[1] Before the 20th century, detachments were commonly considered the result of primary inflammatory or exudative processes, leading to therapeutic attempts that targeted fluid resorption rather than mechanical retinal breaks.[2] This conceptual misunderstanding defined the pre-Gonin era and delayed the development of effective operative approaches.[2]

The modern understanding of RRD—specifically, that subretinal fluid enters through a retinal break in the presence of vitreoretinal traction—formed the basis for all contemporary surgical strategies.[4] From Jules Gonin’s seminal work establishing the causal role of retinal tears, through successive advances in scleral buckling, vitrectomy, and pneumatic retinopexy, RD surgery has undergone more than a century of innovation driven by improvements in visualization, biomaterials, fluidics, and understanding of vitreoretinal pathology.[4]

Today, highly successful outcomes are achieved using a range of techniques including scleral buckling, pars plana vitrectomy, or pneumatic retinopexy, each selected based on detachment configuration, patient characteristics, and surgeon expertise.[5] Reviewing the historical evolution of these methods clarifies the rationale behind modern decision-making, contextualizes ongoing debate regarding optimal approaches, and highlights how conceptual breakthroughs—rather than technology alone—have consistently reshaped the management of retinal detachment.

Pre-Gonin Era: Early Concepts and Attempts (Pre-1900 to ~1920)

Early Descriptions of Retinal Detachment

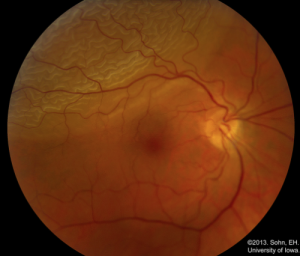

The advent of the ophthalmoscope in the mid-19th century allowed clinicians such as Coccius and von Graefe to visualize retinal detachments directly for the first time.[6] Although retinal breaks were occasionally observed, their significance was not recognized, and detachments were misinterpreted primarily as exudative conditions originating from the choroid or retina. This misattribution created a dominant theoretical framework that viewed RD as an inflammatory or vascular disorder rather than a mechanical one.[7]

Etiologic Theories Before Gonin

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the prevailing belief held that subretinal fluid accumulated due to increased vascular permeability or inflammatory exudation. Because the true mechanisms of vitreoretinal traction and retinal tearing were not yet understood, the concept of a “causal retinal break” did not enter mainstream thinking. As a result, therapeutic strategies failed to address the fundamental pathology, and outcomes remained uniformly poor.[8]

Early Non-Surgical and Surgical Treatments

In the absence of a correct etiologic model, early treatment approaches were empirical and largely ineffective.[9] Commonly attempted methods included prolonged bed rest, bilateral eye patching, medical therapies, and the use of miotics or mydriatics in hopes of altering choroidal circulation. [9]Subretinal fluid drainage was occasionally attempted through scleral puncture; however, without identification or treatment of a retinal break, reattachment was rare and complications were frequent. Thermal and chemical cautery techniques were also explored to induce adhesion between the detached retina and underlying tissues, but these methods lacked precision and carried significant risks[10]. By the end of the 19th century, despite a growing body of clinical observations, the prognosis for retinal detachment remained extremely poor, with reported cure rates of 1–5%. This period is characterized by persistent therapeutic failure not due to lack of effort, but due to the absence of a unifying and accurate understanding of disease pathophysiology.

Transition Toward the Modern Era

By the early 20th century, improved ophthalmoscopy and more careful clinical documentation began to reveal patterns inconsistent with an exudative mechanism, particularly the consistent presence of retinal tears adjacent to areas of detachment. However, the causal relationship remained unrecognized until the pioneering work of Jules Gonin, whose discoveries would fundamentally transform the management of retinal detachment and usher in the first era of successful surgical intervention.

The Gonin Revolution (1902–1935)

Identification of the Retinal Break as the Causal Lesion

The most transformative advance in the history of retinal detachment surgery came from the work of Jules Gonin, who fundamentally shifted the understanding of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.[11] Through meticulous ophthalmoscopic examination and clinical correlation, Gonin observed that a retinal break was not merely an associated finding but the primary cause of subretinal fluid accumulation. This insight overturned the long-standing belief in a primary exudative mechanism and reframed retinal detachment as a mechanical disorder requiring closure of the retinal tear.

Gonin’s recognition of the retinal break as the initiating event provided the first coherent pathophysiologic model for RRD and remains the conceptual foundation of all modern surgical techniques, including scleral buckling, pneumatic retinopexy, and vitrectomy-based repair.[11]

Development of Ignipuncture

To address the causal break, Gonin developed ignipuncture, a technique in which a transscleral cautery probe was applied precisely over the area of the retinal tear. [13]The goal was to create a robust chorioretinal adhesion, effectively sealing the break and preventing further passage of fluid into the subretinal space. In selected cases, limited drainage of subretinal fluid was performed to facilitate retinal apposition, though Gonin emphasized that sealing the break—not drainage—was the essential step.

Ignipuncture represented the first intervention specifically designed to treat the retinal break itself, distinguishing it from earlier, nonspecific therapies. Although primitive by modern standards and associated with complications such as choroidal injury and hemorrhage, ignipuncture profoundly improved outcomes.[13]

Clinical Impact and Controversy

Gonin reported reattachment rates that dramatically exceeded all prior methods, with early success approaching 30–40% and later success rates exceeding 50–60% in select cohorts. These[9] results were met with initial skepticism by many physicians who remained committed to the exudative theory. Gonin’s conclusions challenged decades of dogma, and acceptance was slow despite mounting evidence.

Over time, however, independent replication and clinical observation validated Gonin’s breakthrough. His work ultimately gained international recognition, culminating in his nomination for the Nobel Prize. Although Gonin passed away before the field fully embraced his discoveries, his contributions permanently changed the trajectory of retinal surgery.[9]

The principles established by Gonin—identify the break, create adhesion, and prevent further fluid ingress—are embedded in every modern retinal detachment procedure. Ignipuncture itself was eventually replaced by safer and more controlled modalities, such as cryotherapy and laser photocoagulation, but the conceptual leap he introduced remains one of the most important milestones in ophthalmic history.[11]

Era of Scleral Shortening and Diathermy (1930s–1940s)

Early Attempts at Scleral Shortening

Following Gonin’s death and before the widespread adoption of scleral buckling, surgeons explored various methods aimed at altering the contour of the globe to promote retinal reattachment. One such approach involved scleral shortening, in which partial- or full-thickness scleral resections were performed to reduce the ocular circumference. The goal was to approximate the sclera more closely to the detached retina and indirectly relieve vitreoretinal traction.[14]

While scleral shortening represented a logical extension of Gonin’s mechanical model, these procedures were technically challenging and associated with significant morbidity. Complications included induced high myopia, ocular motility disturbances, scleral thinning, and occasionally severe postoperative pain. Because scleral shortening did not consistently address tractional forces or precisely localize treatment to a retinal break, outcomes were variable and often unsatisfactory.[1]

Development of Transscleral Diathermy

In parallel with scleral shortening, transscleral diathermy emerged as a technique for inducing controlled chorioretinal adhesion. Surgeons applied a heated probe externally to the sclera overlying the retinal break, producing localized thermal injury to create a scar that sealed the break. In Gonin’s era, diathermy had been used in a more rudimentary fashion; by the 1930s and 1940s, refinements in instrumentation permitted deeper and more localized treatment.[15]

Diathermy became a central component of many early retinal detachment surgeries, either alone or in combination with scleral resections or drainage procedures. It improved reattachment rates compared to earlier methods, but the technique still carried risks such as choroidal hemorrhage, excessive scarring, and postoperative inflammation.[15]

Limitations and Transition Toward Buckling Techniques

Despite incremental improvements, scleral shortening and diathermy-based operations were limited by poor visualization of retinal breaks, imprecise targeting of energy delivery, and the inability to effectively relieve vitreoretinal traction. Success rates remained inconsistent, and complications were frequent.

These limitations created momentum for the development of techniques that could both alter scleral contour more predictably and address the break with greater accuracy. This transition paved the way for the emergence of scleral buckling, which would dominate retinal detachment surgery through the mid-20th century and form a bridge to the later development of pars plana vitrectomy.

Emergence and Evolution of Scleral Buckling (1949–1960s): Custodis, Schepens, Cryotherapy, and Lincoff

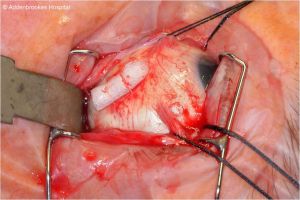

The modern evolution of scleral buckling began in 1949 with the pioneering work of Ernst Custodis, who introduced the first consistently effective method for altering scleral contour to support the retina externally. Custodis used a polyviol episcleral implant positioned directly over the area corresponding to the retinal break, thereby creating a localized indentation that approximated the neurosensory retina to the underlying retinal pigment epithelium.[16] This approach represented a conceptual refinement of Gonin’s principles by providing physical support beneath the break rather than relying solely on thermal adhesion. Custodis also emphasized the importance of a non-drainage technique, observing that subretinal fluid could be reabsorbed once the break was properly closed. Although the procedure relied on transscleral diathermy for chorioretinal adhesion and the polyviol implant occasionally provoked significant inflammation, the essential framework he introduced—external indentation combined with break closure—became the blueprint for subsequent developments in retinal detachment repair.[16]

In the 1950s, Charles Schepens advanced retinal surgery into a more systematic and reproducible discipline. Schepens introduced silicone rubber materials to replace the problematic polyviol explants, marking a major improvement in both biocompatibility and structural stability.[16] Silicone sponges, tires, and later encircling bands became widely adopted because they provided consistent indentation without the complications associated with earlier materials. Schepens also refined the surgical approach by developing lamellar scleral dissection techniques, standardizing the placement of segmental and encircling elements, and integrating careful retinal mapping into preoperative planning.[17] His innovations in indirect ophthalmoscopy and scleral depression dramatically improved the surgeon’s ability to visualize peripheral retinal breaks, which in turn increased the precision of buckle placement and strengthened the conceptual link between identifying the break and tailoring the surgical repair to its location. Under Schepens’ leadership, scleral buckling matured from a promising technique into the predominant method of retinal reattachment for several decades.[17]

During this period, cryotherapy emerged as a transformative adjunct for creating controlled chorioretinal adhesion. Cryotherapy provided a safer and more predictable alternative to diathermy by freezing the tissue directly overlying the retinal break, minimizing collateral damage and reducing complications such as choroidal hemorrhage.[19] Its introduction triggered what became known as the “hot versus cold” debate, referring to the relative merits of diathermy versus cryotherapy in producing effective chorioretinal scarring. Ultimately, cryotherapy gained widespread acceptance due to its precision, reliability, and reproducibility, and it soon became an integral component of scleral buckling surgery. Its adoption helped standardize break treatment in a way that aligned more closely with Gonin’s original principles while reducing the risks associated with earlier thermal methods.[19]

Harvey Lincoff further refined scleral buckling by introducing a rigorously analytical approach to determining the location of retinal breaks. [20]His development of the Lincoff Rules provided surgeons with predictable patterns correlating the configuration of the retinal detachment with the likely position of a causative tear, greatly improving break localization in challenging cases.[20] Lincoff also promoted the concept of minimal, highly targeted surgical intervention. Instead of large encircling procedures for every detachment, he advocated for small, precisely positioned segmental buckles that supported the specific area of pathology while minimizing refractive changes, extraocular muscle disturbances, and postoperative morbidity.[20] His emphasis on non-drainage surgery and controlled use of cryotherapy established a surgical philosophy that prioritized anatomical logic, tissue preservation, and strategic minimalism. Integrating these refinements with the improved visualization techniques developed by Schepens created an era in which scleral buckling became both anatomically sophisticated and surgically efficient.[20]

By the late 1960s, the combined contributions of Custodis, Schepens, cryotherapy innovators, and Lincoff had transformed scleral buckling into the gold standard for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.[17] Primary reattachment rates for uncomplicated detachments frequently exceeded 70–80%, a dramatic improvement over the outcomes of earlier decades. Surgeons now had a reliable, repeatable method grounded in the principles of break identification, precise buckle placement, controlled chorioretinal adhesion, and selective use of subretinal fluid drainage. Although later techniques such as pars plana vitrectomy would further expand the surgical armamentarium, the scleral buckling era established the core mechanical and physiologic principles that continue to guide retinal detachment repair. It also provided the first widely adopted framework for individualized surgical planning based on detachment configuration, break location, and tractional forces—concepts that remain foundational in vitreoretinal surgery today.[17]

Development of Vitreous Surgery and the Advent of Pars Plana Vitrectomy (Late 1960s–1980s)

Early Attempts at Vitreous Removal

Before the development of closed-system vitrectomy, surgeons attempting to treat complex retinal detachments were limited by the inability to access or remove vitreous opacities, tractional membranes, or organized blood.[21] Early open-sky vitrectomy, exemplified by David Kasner’s work in the late 1960s, allowed removal of dense vitreous opacities but required temporary keratoplasty and exposed the eye to significant fluctuations in intraocular pressure.[21] Although these procedures demonstrated that vitreous abnormalities played a meaningful role in retinal pathology, they were unsuitable for widespread use due to the high surgical risk and lack of intraoperative control.[21]

Machemer and the Closed-System Pars Plana Vitrectomy

The pivotal transformation occurred with Robert Machemer’s development of the first closed-system pars plana vitrectomy (PPV). His Vitreous Infusion Suction Cutter (VISC) permitted simultaneous cutting and aspiration of vitreous while maintaining intraocular pressure through continuous infusion.[22] By entering the eye via the pars plana, the surgeon could manipulate the posterior segment without disturbing the crystalline lens or cornea.[22] This innovation created, for the first time, a controlled intraocular environment suitable for addressing pathologic vitreous traction directly.[22]

Machemer’s initial one-port vitrectomy system was soon improved by O’Malley and Heintz with the introduction of a three-port technique, separating infusion, illumination, and instrumentation. This configuration enabled stable intraocular pressure, improved visualization, and greater operative dexterity.[22] As surgeons gained experience, the role of PPV expanded rapidly beyond vitreous hemorrhage and proliferative diabetic retinopathy to include increasingly complex forms of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.[22]

Application of PPV to Retinal Detachment Repair

The adoption of PPV for retinal detachment provided advantages that scleral buckling alone could not.[23] PPV allowed surgeons to remove tractional elements such as adherent vitreous cortex, epiretinal membranes, and early proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Internal drainage of subretinal fluid through the retinal break offered a controlled method of retinal reattachment, allowing precise flattening of the posterior pole before definitive break closure.[23] The use of intraocular tamponade agents, including expansile gases and silicone oil, extended postoperative retinal support and improved outcomes in cases with multiple breaks, pseudophakia, giant retinal tears, and advanced vitreoretinopathy.[23]

Emergence of Adjuvant Tools and Improved Visualization

The introduction of wide-angle viewing systems, chandelier illumination, and perfluorocarbon liquids further refined PPV for complex detachments. Perfluorocarbon liquids enabled surgeons to stabilize mobile retina, unfold giant tears, and manipulate posterior pathology with unprecedented control.[24] Over time, fluidics technology improved, cutting speeds increased dramatically, and vitrectomy became safer and more efficient. By the late 1980s, PPV was firmly established as a major surgical modality capable of addressing detachment configurations previously considered inoperable.[24]

Pneumatic Retinopexy and the Expansion of Minimally Invasive Repair (1980s Onward)

Conceptual Basis and Early Development

Pneumatic retinopexy emerged in the 1980s as a minimally invasive alternative to scleral buckling and PPV for selected retinal detachments. The procedure involved intravitreal injection of a long- or short-acting gas bubble followed by precise postoperative head positioning to tamponade the retinal break.[25] Once the break was apposed, cryotherapy or laser photocoagulation was applied to achieve permanent chorioretinal adhesion.[25] This technique represented a conceptual return to Gonin’s principle that sealing the break could restore anatomic integrity, but it did so without altering scleral contour or requiring intraocular dissection.[25]

Ideal Case Selection and Advantages

Pneumatic retinopexy was best suited for detachments involving one or a few small retinal breaks located in the superior quadrants. Phakic patients without significant proliferative vitreoretinopathy demonstrated the highest success rates.[25] Its minimally invasive nature allowed the procedure to be performed in the office, reduced operative time, and minimized postoperative morbidity. Many patients experienced faster visual recovery due to the absence of surgical incisions or extraocular muscle manipulation.[25]

Limitations and Controversies

Despite its advantages, pneumatic retinopexy required strict adherence to positioning protocols, and surgical success was highly dependent on accurate identification of all breaks. Undetected inferior or posterior breaks, inadequate tamponade, and poor compliance with positioning contributed to redetachment in a subset of cases. In addition, the technique had lower initial reattachment rates than either scleral buckling or vitrectomy in cases with more complex detachment anatomy. Over time, pneumatic retinopexy found its role as an efficient, targeted option rather than a universal primary repair method. It remains valuable today for appropriately selected patients but does not replace vitrectomy or buckling in more challenging presentations.[26]

Modern Era of Retinal Detachment Repair: Transition to Vitrectomy-Dominant Management (1990s–Present)

Shift Toward Pars Plana Vitrectomy as Primary Repair

Beginning in the 1990s, improvements in vitrectomy instrumentation, viewing systems, and postoperative tamponade led to a progressive shift toward PPV as the primary repair strategy for many rhegmatogenous detachments. Surgeons increasingly recognized that vitreous traction—rather than external geometry alone—played a central role in the creation and persistence of retinal breaks. PPV enabled direct removal of tractional forces, internal drainage of subretinal fluid, and precise endolaser photocoagulation. These capabilities, combined with expanding training in vitreoretinal surgery, resulted in widespread adoption of PPV for pseudophakic detachments, detachments with posterior breaks, and cases with early proliferative vitreoretinopathy.[27]

Advent of Microincision Vitrectomy Surgery (MIVS)

The transition to 23-, 25-, and subsequently 27-gauge transconjunctival vitrectomy systems further accelerated the shift toward PPV. Smaller-gauge sclerotomies allowed sutureless entry, reduced postoperative inflammation, and shortened visual recovery time. [28]Advances in fluidics provided stable intraocular pressure control even with very small instruments, while modern vitreous cutters achieved ultra-high cutting rates that minimized traction on the retina and optic nerve. These innovations made PPV safer, more efficient, and increasingly suitable even for routine primary detachments.[28]

Contemporary Role of Scleral Buckling and Combined Techniques

Although PPV has become the dominant surgical approach in many regions, scleral buckling retains an important role. Younger, highly myopic, and phakic patients often benefit from buckling because it preserves the crystalline lens and avoids the accelerated cataract formation associated with vitrectomy.[29] Buckling also remains valuable for localized, break-specific detachments, especially when the breaks lie anterior to the equator or when vitreous traction is minimal. In more complex presentations—such as advanced proliferative vitreoretinopathy, extensive lattice degeneration, or detachments with both tractional and rhegmatogenous components—surgeons may combine PPV with an encircling buckle to address both internal and circumferential tractional forces.[29]

Technologic Enhancements in the Modern Era

The modern surgical toolbox includes perfluorocarbon liquids for stabilizing mobile retina, endolaser photocoagulation for precise break closure, and a refined selection of tamponade agents adapted to detachment pattern and patient needs.[30] Wide-field viewing systems, often integrated with heads-up digital display platforms, have enhanced surgical visualization and increased precision. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography adds another layer of intraoperative feedback, assisting with membrane peeling and confirming retinal apposition.[30]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wolfensberger TJ. Jules Gonin: pioneer of retinal detachment surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003;51(4):303-308. Rumpf J. Jules Gonin. Inventor of the surgical treatment for retinal detachment. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976;21(3):276-284.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Yamaguchi M, Ataka S, Shiraki K. Subretinal fluid drainage via original retinal breaks for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jun;49(3):256-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.03.001. PMID: 24862771.

- ↑ Strohbehn A, Sohn EH. Retinal Detachment: From One Medical Student to Another. EyeRounds.org. October 15, 2013. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/tutorials/retinal-detachment-med-students/index.htm

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sultan ZN, Agorogiannis EI, Iannetta D, Steel D, Sandinha T. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a review of current practice in diagnosis and management. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020 Oct 9;5(1):e000474. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000474. Erratum in: BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar 14;6(1):e000474corr1. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000474corr1. PMID: 33083551; PMCID: PMC7549457.

- ↑ Stewart S, Chan W. Pneumatic retinopexy: patient selection and specific factors. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018 Mar 16;12:493-502. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S137607. PMID: 29588570; PMCID: PMC5859893.

- ↑ Ivanišević M. First look into the eye. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019 Nov;29(6):685-688. doi: 10.1177/1120672118804388. Epub 2018 Oct 7. PMID: 30295065.

- ↑ Fraser S, Steel D. Retinal detachment. BMJ Clin Evid. 2010 Nov 24;2010:0710. PMID: 21406128; PMCID: PMC3275330.

- ↑ Ivanišević M. First look into the eye. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019 Nov;29(6):685-688. doi: 10.1177/1120672118804388. Epub 2018 Oct 7. PMID: 30295065.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Wolfensberger TJ. Jules Gonin. Pioneer of retinal detachment surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003 Dec;51(4):303-8. PMID: 14750617.

- ↑ Laqua H, Machemer R. Repair and adhesion mechanisms of the cryotherapy lesion in experimental retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976 Jun;81(6):833-46. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90368-8. PMID: 820201.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Xiong J, Tran T, Waldstein SM, Fung AT. A review of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: past, present and future. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2025 May;175(7-8):186-202. doi: 10.1007/s10354-025-01085-9. Epub 2025 Apr 4. PMID: 40183886; PMCID: PMC12031774.

- ↑ Peter N. Jules Gonin. Entrevoir: Le blog de la Fondation Asile des aveugles. Published June 7, 2019. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://blog.ophtalmique.ch/2019/06/07/jules-gonin/

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rumpf J. Jules Gonin. Inventor of the surgical treatment for retinal detachment. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976 Nov-Dec;21(3):276-84. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(76)90125-9. PMID: 797030.

- ↑ Pal BP, Saurabh K. Evolution of Retinal Detachment Surgery Down the Ages. Sci J Med & Vis Res Foun. 2017;XXXV:3-6. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ophed.com/system/files/2021/01/History%20of%20RD%20surgery%202017.pdf

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jabbour NM, McCormick SA, Gong HY. Transscleral and transconjunctival diathermy. Retina. 1989;9(2):127-30. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198909020-00011. PMID: 2772420.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Wang A, Snead MP. Scleral buckling-a brief historical overview and current indications. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar;258(3):467-478. doi: 10.1007/s00417-019-04562-1. Epub 2019 Dec 11. PMID: 31828426.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Cruz-Pimentel M, Huang CY, Wu L. Scleral Buckling: A Look at the Past, Present and Future in View of Recent Findings on the Importance of Photoreceptor Re-Alignment Following Retinal Re-Attachment. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022 Jun 16;16:1971-1984. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S359309. PMID: 35733617; PMCID: PMC9208732.

- ↑ Wang A, Snead MP. Scleral buckling—a brief historical overview and current indications. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(3):467-478. Published December 11, 2019. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00417-019-04562-1

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Glaser BM, Vidaurri-Leal J, Michels RG, Campochiaro PA. Cryotherapy during surgery for giant retinal tears and intravitreal dispersion of viable retinal pigment epithelial cells. Ophthalmology. 1993 Apr;100(4):466-70. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31620-9. PMID: 8479702.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Azad SV, Takkar B, Bhatia I, Azad R. LINCOFF RULES ARE NOT FOLLOWED IN RETINAL DETACHMENT WITH POSTERIOR BREAKS AND ATTACHED CORTICAL VITREOUS. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2019 Winter;13(1):21-24. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000522. PMID: 30562236.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Grzybowski A, Kanclerz P. EARLY DESCRIPTIONS OF VITREOUS SURGERY. Retina. 2021 Jul 1;41(7):1364-1372. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003149. PMID: 33595257.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Machemer R. The development of pars plana vitrectomy: a personal account. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995 Aug;233(8):453-68. doi: 10.1007/BF00183425. PMID: 8537019.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Znaor L, Medic A, Binder S, Vucinovic A, Marin Lovric J, Puljak L. Pars plana vitrectomy versus scleral buckling for repairing simple rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 8;3(3):CD009562. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009562.pub2. PMID: 30848830; PMCID: PMC6407688.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Arevalo JF. Perfluorocarbon liquid vitreous delamination and wide-angle viewing system in the management of complicated diabetic retinal detachment. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010 Mar-Apr;20(2):490; author reply 491. doi: 10.1177/112067211002000243. PMID: 20213625.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Hatef E, Sena DF, Fallano KA, Crews J, Do DV. Pneumatic retinopexy versus scleral buckle for repairing simple rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 May 7;5(5):CD008350. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008350.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Nov 11;11:CD008350. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008350.pub3. PMID: 25950286; PMCID: PMC4451439.

- ↑ Cohen E, Zerach A, Mimouni M, Barak A. Reassessment of pneumatic retinopexy for primary treatment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov 2;9:2033-7. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S91486. PMID: 26586932; PMCID: PMC4636098.

- ↑ Schwartz SG, Flynn HW. Pars plana vitrectomy for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008 Mar;2(1):57-63. doi: 10.2147/opth.s1511. PMID: 19668388; PMCID: PMC2698718.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Mohamed S, Claes C, Tsang CW. Review of Small Gauge Vitrectomy: Progress and Innovations. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:6285869. doi: 10.1155/2017/6285869. Epub 2017 May 10. PMID: 28589037; PMCID: PMC5447313.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Park SW, Lee JJ, Lee JE. Scleral buckling in the management of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: patient selection and perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018 Aug 30;12:1605-1615. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S153717. PMID: 30214145; PMCID: PMC6124476.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Kohli P, Tripathy K. Agents for Vitreous Tamponade. [Updated 2023 Aug 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580519/