Iris Microhemangiomas

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Iris microhemangioma (also known as iris vascular tufts or Cobb’s tufts) are rare, bilateral, benign vascular lesions of the iris characterized by tiny, tangled blood vessels at the pupillary margin[1][2]. They are considered a form of hamartomatous hemangioma (not a true neoplasm) and typically remain small and clinically silent. First described in association with myotonic dystrophy by Cobb in 1970[3], these lesions are usually an incidental finding on slit-lamp exam or may come to attention after a spontaneous hyphema (anterior chamber bleeding). Iris microhemangioma represent one of the few vascular tumors of the iris (comprising about 2% of all iris tumors)[1][2]. While generally innocuous, they gain clinical importance due to their potential to cause recurrent hyphema and secondary glaucoma.

Epidemiology

Iris microhemangioma are rare lesions, with only around 90 cases reported in the literature up to the mid-2000s[4]. They typically present in middle-aged to older adults. A review of cases reported the age at presentation ranging from about 42 to 80 years[5], with a more recent series showing a mean age around 70 years[6]. There is no clear sex or racial predilection, although many reported patients have been of Caucasian descent (possibly reflecting detection bias due to lighter irides)[5]. These microvascular tufts are often present bilaterally. Older reports noted they are “usually bilateral” and more than half of patients in a modern case series had bilateral lesions[1][6]. There is no known hereditary pattern or familial clustering of iris microhemangioma; they generally appear sporadically in individuals.

Etiology

The exact cause of iris microhemangioma remains uncertain[1]. Earlier authors considered them developmental anomalies of the iris vasculature, whereas more recent understanding leans toward an acquired, degenerative microvascular proliferation (distinct from ischemia-driven neovascularization)[1]. Histopathologically, they consist of small, twisted or coiled blood vessels lined by endothelium within the iris stroma[1][2][6]. These tangles of tiny vessels are typically located at the pupillary margin, giving the appearance of minute red tufts on the iris surface. Unlike iris neovascularization due to diabetic or ischemic eye disease, iris microhemangioma are not caused by angiogenic factors; instead, they behave more like benign telangiectasias or hamartomas[1][2][6]. The vessel walls may be relatively weak, which explains their tendency to bleed spontaneously. Notably, iris microhemangioma are not part of a systemic hemangiomatosis (as diffuse neonatal hemangiomas are) – they are localized lesions. Their association with certain systemic conditions (see Systemic Associations below) suggests that generalized microangiopathic processes might play a role in their development in some patients[1].

Systemic Associations

A notable aspect of iris microhemangioma is their association with certain systemic conditions. Although many patients have no systemic disease, a significant number of reported cases occur in individuals with underlying disorders[1][4][5]. Key associations include:

- Myotonic Dystrophy (Steinert disease): This is the most famous association. About half of patients with myotonic dystrophy were found to have iris vascular tufts in one study[4]. In fact, these lesions were first highlighted by Cobb in 1970 when observing ocular findings in myotonic dystrophy[3]. The mechanism is not fully understood, but it may reflect a generalized microangiopathy in myotonic dystrophy[1][3]. Ophthalmologists should be aware that discovering bilateral iris microhemangioma might warrant a review of systems for myotonic dystrophy features if not already diagnosed.

- Diabetes Mellitus: Adult-onset diabetes (Type 2) has been frequently noted in patients with iris microhemangioma[1]. Unlike diabetic iris neovascularization (rubeosis), these vascular tufts are not caused by ischemia, but diabetes could predispose to microvascular abnormalities. In any diabetic patient, one must distinguish true neovascularization from benign microhemangioma; the latter tend to be more localized and static[2][6].

- Chronic Respiratory Disease: Conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been reported in higher incidence among patients with iris microhemangioma[5][6]. Chronic hypoxemia or systemic vascular stress might play a contributory role.

- Congenital Heart Disease: Particularly cyanotic heart disease (e.g. Eisenmenger syndrome) has been associated with these iris lesions[1]. There is a case report of an Eisenmenger patient presenting with spontaneous hyphema from an iris microhemangioma[7]. It’s hypothesized that long-standing hypoxia or altered hemodynamics could promote such microvascular changes.

- Idiopathic Juxtafoveolar Retinal Telangiectasia: This is an unrelated retinal microvascular disorder, but intriguingly, a case was documented where a patient had both idiopathic perifoveal telangiectasia (MacTel) and iris microhemangiomatosis[4][2]. Both are idiopathic telangiectatic conditions, suggesting a possible common predisposition in vascular regulation.

- Other ocular vascular conditions: Rarely, iris microhemangioma have co-occurred with retinal vein occlusion or other vascular anomalies, though causal links are unclear[1]. Most patients, however, do not have an ocular ischemic condition (and indeed, the presence of microhemangioma should not be mistaken for rubeosis from a vein occlusion or diabetic eye disease).

It’s important to emphasize that many patients have no systemic disease at all[1][6]. The presence of iris microhemangioma should prompt a thoughtful review of systemic history (e.g. asking about muscle weakness (for dystrophy), diabetes status, cardiopulmonary issues), but in the absence of other clues, extensive systemic work-up is usually not necessary. In summary, while iris microhemangioma are primarily an ocular condition, they sometimes serve as a subtle clue to systemic illnesses that affect microvasculature, and general ophthalmologists should keep these associations in mind.

Diagnosis

History

Most patients with iris microhemangioma are asymptomatic unless a complication occurs. Patients may report a history of ocular pain or vision loss in one or both eyes secondary to elevated intraocular pressure during bleeding episodes. Some patients describe prior evaluations for spontaneous hyphema and secondary glaucoma. A history of ocular trauma is not required. It is not uncommon for iris microhemangioma to remain undiagnosed, particularly when bleeding episodes are mild, self-limited, or attributed to other causes.

Physical Examination

Signs

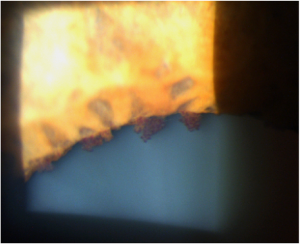

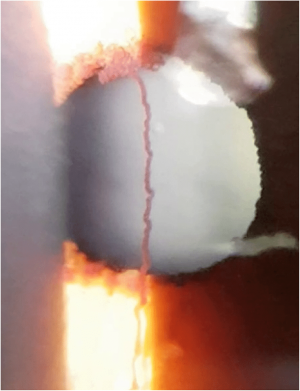

On clinical examination with a slit lamp, these lesions appear as tiny red or reddish-brown nodules at the superior pupillary border usually bilaterally. They can be subtle, often requiring high magnification to discern, especially in darker-colored irises. Typically, multiple microhemangioma are present, scattered circumferentially around the pupil margin, and they are usually flat or only slightly raised.

These iris vascular tufts do not generally affect vision or pupil function directly. However, a proportion of patients experience spontaneous hyphema (bleeding into the anterior chamber) when one of the tufts ruptures. Such bleeding episodes may cause sudden blurry vision or visual obstruction (if the hyphema is large), along with acute ocular discomfort. In many cases, the hyphema is small (“microhyphema” or layered red blood cells) and self-limited[5]. Recurrent hyphemas can occur, sometimes leading to elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) due to trabecular meshwork obstruction by red blood cells. In a series of 22 eyes with iris microhemangiomatosis, about half had at least one hyphema and a third developed secondary glaucoma from these bleeds[6]. Aside from hyphema, iris microhemangioma rarely cause any pain or inflammation (they do not typically induce iris inflammation/uveitis). The anterior chamber is usually deep and quiet unless blood is present. Visual acuity may transiently decrease during a bleed (due to blood obscuring the visual axis or corneal blood staining in severe cases), but otherwise patients maintain normal vision if no other ocular issues exist. Importantly, iris microhemangioma are benign and do not progressively enlarge or transform into malignancy. The main risk is related to bleeding episodes and their sequelae (staining, elevated IOP, etc.), which can usually be managed.

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis is primarily clinical. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy reveals the characteristic tiny vascular tufts at the pupillary edge. These should be differentiated from other causes of abnormal iris vessels. Gonioscopy is useful to examine the angle and confirm that there is no angle neovascularization (rubeosis iridis), which can look somewhat similar but is typically associated with diabetes or ischemic retinal disease and extends over the iris surface and angle[1][2]. In iris microhemangioma, the vessels are mostly confined to the pupillary margin and are not accompanied by the fibrovascular membranes seen in rubeosis[1][5]. The presence of isolated pupillary-margin tufts in an otherwise healthy eye strongly favors microhemangioma over pathologic neovascularization.

Diagnostic Procedures

Ancillary imaging can support the diagnosis. Iris fluorescein angiography (FA) is a classic diagnostic tool: it shows early filling of the pupillary margin microvascular tufts with fluorescence and mild late staining, but importantly no significant leakage of dye[6]. This contrasts with rubeosis iridis vessels, which tend to leak profusely in late phases. FA can highlight even subtle microhemangioma that are hard to see clinically, and it helps confirm the extent of lesions[1][5][6]. Newer imaging modalities like anterior segment optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) can noninvasively detect blood flow in these minute iris vessels, and ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) or high-resolution AS-OCT may demonstrate the structural prominence of a tuft if present (though often these lesions are so small that UBM/AS-OCT findings are minimal)[2][6]. In practice, specialized imaging is often not required unless there is diagnostic uncertainty or recurrent bleeding.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for iris microhemangioma includes other vascular lesions of the iris: capillary hemangioma of the iris (usually in infants, often multiple reddish masses), cavernous hemangioma (also in childhood, a multilobulated blood-filled lesion), and iris varix (an enlarged, floppy iris vein that can mimic a hemangioma)[1][2][6]. Unlike those, iris microhemangioma occur in adults and are much smaller in caliber[1][2][6]. Distinguishing microhemangioma from early rubeosis iridis is critical: microhemangioma tend to be more localized, not associated with diabetic retinopathy signs, and have the angiographic behavior noted above[1][2][6].

Management

Medical Therapy

Because iris microhemangioma are benign and often asymptomatic, conservative management is the rule. In patients without any history of hyphema, or with a single minor hyphema, careful observation is recommended[5][6]. Periodic exams should monitor for new bleeding. Patients are often counseled to avoid unnecessary trauma or strenuous activities that might precipitate a bleed (though many bleeds are spontaneous). If a hyphema occurs, initial management is similar to any spontaneous hyphema: elevate the head, rest, and use medications to prevent complications. Topical corticosteroids can help stabilize the blood-aqueous barrier and reduce any inflammatory response to blood, and cycloplegic drops (e.g. cyclopentolate) are used to keep the pupil dilated and iris immobile, potentially aiding in hemostasis[1][2][6]. IOP should be monitored and controlled with aqueous suppressants if elevated[1][2][6]. These measures usually allow the hyphema to resolve over days. There are also reports of using anti-fibrinolytic therapy (e.g. systemic tranexamic acid) in acute bleeding episodes to promote clot stability, though this is not standard and is considered on a case-by-case basis[8].

Laser & Surgery

For patients who suffer recurrent hyphema or persistent bleeding from an iris microhemangioma, intervention is indicated. Argon laser photocoagulation directed at the iris vascular tuft is the most commonly reported treatment to obliterate the abnormal vessel and prevent further hemorrhage[2]. Laser treatment can be guided by iris FA to pinpoint feeder vessels[4]. Typically, a series of laser spots is applied to coagulate the tiny lesion; this often results in fibrosis or closure of the abnormal microvessels. Case reports have shown that laser photocoagulation successfully stops recurrent bleeds and even permits safe intraocular surgery afterward[4]. In a comprehensive review, only about 9% of eyes with iris microhemangiomatosis required laser photocoagulation – the vast majority were managed with observation alone[6]. More invasive surgical intervention (such as sector iridectomy to excise the lesions) is rarely necessary, and generally reserved for extreme cases not responsive to laser or in situations where laser is not feasible. Importantly, if a patient with known iris microhemangioma is planning to undergo intraocular surgery (e.g. cataract surgery), prophylactic laser treatment of prominent tufts may be considered to reduce the risk of intraoperative or postoperative hyphema[4].

Prognosis

The long-term prognosis for patients with iris microhemangioma is excellent in most cases. These lesions are benign and do not grow or metastasize. Many patients will never experience a hyphema or will have only a single mild episode. Even in those with recurrent hyphemas, timely intervention (medical or laser) usually prevents serious sequelae. Visual outcomes are generally good; permanent vision loss is uncommon. However, complications can arise if repeated bleeds are not managed – for example, prolonged elevated IOP from recurrent hemorrhages can lead to glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Fortunately, with appropriate treatment, the risk of such complications is low. In documented case series, nearly all eyes maintained or recovered good vision[6]. Only rare cases of severe hemorrhagic complications (e.g. total hyphema with corneal blood staining or intractable glaucoma) have been reported[2]. Once an offending iris microhemangioma is successfully ablated with laser, the problem is usually cured for that eye. Overall, general ophthalmologists can reassure patients that iris microhemangiomatosis is a benign condition with a high likelihood of favorable outcome, while also educating them on the importance of follow-up and prompt reporting of any new visual disturbances.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Roberts DK, Haine CL. Iris microhemangiomas. J Am Optom Assoc. 1988;59(10):780–784

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Moran CORE. Iris Microhemangiomatosis. University of Utah, John A. Moran Eye Center. Available at: https://morancore.utah.edu/section-04-ophthalmic-pathology/iris-microhemangiomatosis/. Accessed [January 23, 2026].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Cobb B, Shilling JS, Chisholm IH. Vascular tufts at the pupillary margin in myotonic dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;69(4):573–582[3].

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Méndez-Cepeda, P., Viso, E., Sevillano, C., & Lugo, E. (2014). Iris microhaemangiomas: Presentation of a case. Archivos de la Sociedad Española de Oftalmología (English Edition), 89(2), 74-76.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Dharmasena, Aruna, and Simon Wallis. "Iris microhaemangioma: a management strategy." International Journal of Ophthalmology 6.2 (2013): 246.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 Williams BK Jr, Di Nicola M, Ferenczy S, Shields JA, Shields CL. Iris microhemangiomatosis: clinical, fluorescein angiography, and optical coherence tomography angiography features in 14 consecutive patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;196:18–25[27]

- ↑ Ison, Matthew, Andrew Dorman, and Fraser Imrie. "Spontaneous hyphema from iris microhemangioma in Eisenmenger syndrome." American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports 26 (2022): 101536.

- ↑ Ahmed, Umar, Elizabeth Saldana, Matthew Seager, and Tasnim Kamal. "Use of Intravenous Tranexamic Acid for Acute Management of Active Bleeding From Iris Microhaemangioma Presenting as Spontaneous Hyphema." Cureus 17, no. 8 (2025): e90014.