Liquid Biopsy in Ocular Oncology

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

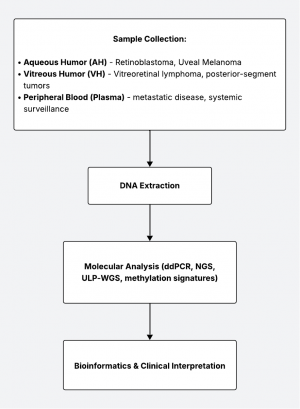

Liquid biopsy is a rapidly advancing diagnostic approach that detects tumor-derived molecules—such as cell-free DNA (cfDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), RNA, and exosomes—from bodily fluids. In ocular oncology, where tissue biopsy can be risky or contraindicated, liquid biopsy offers a minimally invasive alternative for diagnosis, prognosis, and disease monitoring. Intra-ocular fluids (aqueous and vitreous humor) and systemic blood can serve as reservoirs for tumor DNA. Techniques such as droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), next-generation sequencing (NGS), and methylation profiling allow identification of tumor-specific genetic changes with increasing sensitivity.

This article reviews the clinical utility of liquid biopsy across retinoblastoma (RB), uveal melanoma (UM), and primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL), summarizes current evidence, and highlights future opportunities in precision ocular oncology.

Sampling Methods and Techniques

| Fluid | Common Indication | Typical Volume | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous humor | Retinoblastoma, anterior uveal melanoma | 50–150 µL | Safe, minimally invasive, reproducible | Low DNA yield |

| Vitreous humor | PIOL, posterior tumors | 200–500 µL | Larger volume, proximity to tumor | More invasive |

| Plasma | Uveal melanoma (metastatic) | 10 mL | Systemic representation | Low shedding in early disease |

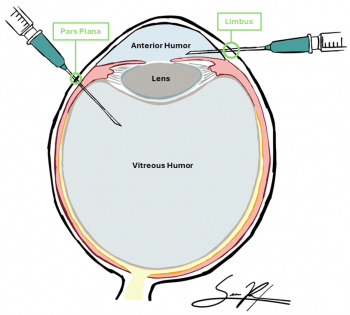

Aqueous Humor Sampling

Technique: Typically via clear corneal paracentesis (anterior chamber tap), often using a 30–32 G needle under sterile conditions.[1][2][3][4] In ocular oncology settings, this is done carefully in a controlled environment.[3]

Safety: Recent safety studies (e.g., in pediatric RB) indicate that aqueous humor taps are well tolerated with minimal adverse events when performed by experienced ocular oncologists.[1]

Volume: Small volumes (e.g. 50–150 µL) are typical; maximizing yield while preserving ocular integrity is key.[1][5][6]

Timing: Sampling before treatment (baseline) and possibly post-treatment (e.g. after radiation or chemotherapy) may help capture dynamic cfDNA shedding.[4][7][8]

Challenges: Small volume, dilution effects, and contamination (blood, cellular debris) are risks, as these may impact downstream molecular analysis.[1][5][9]

Vitreous Humor Sampling

Technique: Performed during a pars plana vitrectomy or vitreous tap, ideally at surgery start before infusion.[9]

Use-case: Most commonly used in intraocular lymphoma (e.g. PIOL) or suspected vitreoretinal tumors.[9][10]

Considerations: More invasive and with higher risks of retinal detachment, hemorrhage, and infection than aqueous taps due to larger fluid volumes; potential light scattering, dilution by irrigation, and cell debris must be managed.[9][10]

Advantage: Larger sampled fluid volume allows for improved diagnostic yield, and sampling of the vitreous allows closer proximity to posterior segment tumors.[9][10]

Plasma / Systemic Sampling

Technique: Standard venous blood draw (e.g. 10 mL, processed to plasma).[5]

Use-case: For tumors that disseminate hematogenously (e.g. UM metastases), plasma cfDNA or circulating tumor cells (CTCs) may provide systemic signal.[5][11]

Challenges: Low tumor DNA shedding in early/local disease, dilution by background cell-free DNA, and temporal fluctuations.[5][11]

Pre-analytical Considerations & Variables

- Use of sterile technique and prompt centrifugation (double-spin)

- Variable(s): DNA extraction method, input volume, centrifugation speed & protocol

- Avoid hemolysis and multiple freeze–thaw cycles

- Variable(s): proper storage conditions/temperature (–80°C)

- Validate extraction kit efficiency

- Variable(s): time delay from sampling to processing

- Quality control

- Variable(s): human genomic DNA contamination, fragment size distributions

Because analyte concentrations can be low, these variables substantially affect sensitivity and reproducibility, and thus should be heavily considered.[1][8][9]

Molecular Techniques and Biomarkers

| Technique | Analyte | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ddPCR | cfDNA | 0.1% VAF | Fast, targeted | Requires known mutation | RB1, MYD88 |

| Targeted NGS | cfDNA | 0.5–1% VAF | Multiplex detection | Costly, deeper coverage needed | GNAQ, GNA11, BAP1 |

| Methylation profiling | cfDNA | Variable | Tumor-specific epigenetic signature | Complex analysis | UM subclassification |

| Low-pass whole-genome sequencing | cfDNA | Moderate | Detects CNVs | Requires bioinformatics | Monosomy 3, 8q gain |

| Exosomal RNA/miRNA | Exosomes | Low | Adds functional insights | Less validated | Diagnostic adjunct |

Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) / Quantitative PCR[12][13][14]

Widely used for hotspot mutation detection; e.g. RB1 (retinoblastoma), GNAQ/GNA11 (uveal melanoma), MYD88 L265P (primary vitreoretinal lymphoma). Offers high sensitivity (down to variant allele fractions ~0.1% or lower), and quantitation across time. Particularly suited when the target mutation is known a priori (i.e. tailored assays). In ocular oncology, ddPCR is often the first-line assay for ctDNA detection due to lower cost and simplicity.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) & Targeted Panels[5][7][15][16][17]

Enables multiplexed detection or mutations, copy-number alterations (CNAs), structural variants, and/or gene fusions. NGS-based approaches, such as shallow whole-genome sequencing and targeted hybridization panels, can be used to identify somatic variants & CNAs such as monosomy 3 and 8q amplification in uveal melanoma and retinoblastoma to provide prognostic information and therapy guidance. Examples: hybrid-capture panels, amplicon-based panels, ultra-deep sequencing with molecular barcodes. Allows discovery of unexpected mutations or broad profiling but may suffer in sensitivity compared to ddPCR if depth is not sufficient. Targeted panels can simultaneously assess single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and CNAs in matched tumor and liquid biopsy samples.[15] In ocular fluids, depth (read coverage) and error correction are critical to detect low-frequency variants.

Methylation / Epigenetic Profiling[18][19]

Methylation and epigenetic profiling are increasingly utilized to identify tumor-specific DNA methylation signatures in cell-free DNA from aqueous humor and plasma, which may be more robust in distinguishing tumor-derived DNA from background. Techniques may include bisulfite sequencing, methylation arrays, or methylation-specific PCR. In ocular oncology, methylation profiling is emerging (less mature), but could enhance sensitivity and specificity, especially when mutation burden is low.

Copy Number Variation (CNV) & Chromosomal Alteration Analysis

Gains or losses (e.g., monosomy 3, 8q amplification) carry prognostic significance in UM; detection via shallow whole-genome sequencing (sWGS) or low-coverage NGS is possible.[16][20] sWGS of blood-derived ctDNA is feasible for CNV profiling particularly in metastatic disease, and chromosome 3 loss detected in ctDNA corresponds to high metastatic risk.[16][20] In aqueous humor, sWGS and targeted sequencing can identify somatic copy number alterations and mutations, especially in post-radiation ciliary body melanoma, with high concordance to matched tumor tissue.[21] Deep amplicon sequencing of aqueous humor has shown a strong association between detectable tumor DNA and monosomy 3 status.[22] Chromosomal aberrations can complement mutation detection in establishing tumor signature. Combining mutation and CNV data can enhance prognostic accuracy and informs personalized treatment strategies in uveal melanoma.[23][24]

Other Analytes

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): Differential expression in tumor vs normal, sometimes detectable in aqueous/vitreous & plasma.[21][25]

- Exosomes / Extracellular Vesicles: Contain DNA, RNA, proteins; stable sources of tumor-derived nucleic acids and proteins and thus can enrich tumor signal.[13]

- Circulating RNA / ctRNA: Less stable but may be informative in select settings.[25]

- Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): Rare in ocular tumors but have been evaluated especially in UM metastasis settings; their presence is associated with high-risk chromosomal alterations and epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene expression.[26]

These molecular techniques enable noninvasive, real-time tumor profiling and disease monitoring in ocular oncology, with each method offering distinct advantages and limitations depending on the clinical context and analyte concentration.[27][28][29][30]

Disease-Specific Applications

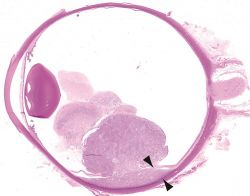

Retinoblastoma (RB)

Rationale: Tissue biopsy is contraindicated due to the risk of extraocular tumor spread; liquid biopsy, specifically analysis of cfDNA from the aqueous, provides safe molecular insight.[2][6][15]

Fluid: Aqueous humor is considered superior to plasma for detecting RB1 mutations and CNVs. Aqueous humor contains higher concentrations of tumor-derived cfDNA, enabling more sensitive detection of RB1 mutations and somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) (i.e. 6p or 1q gain), compared to plasma, which is limited by the blood-ocular barrier and lower tumor DNA yield.4,7,15,17 Plasma cfDNA can detect RB1 mutations, but may be less reliable for intraocular disease monitoring due to its lower sensitivity.[32][33]

Common Alterations: RB1 mutations, 6p gain, 1q gain, CNVs[7][15][17]

- Diagnostic confirmation

- Prognosis prediction (chromosomal instability, i.e. 6p gain, correlates with poor outcome)

- Monitoring treatment response

- Early relapse detection via serial sampling

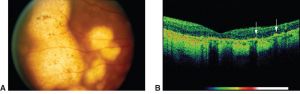

Primary Intraocular Lymphoma (PIOL)

Rationale: Cytology often fails due to cell lysis and low cellularity in vitreous samples; molecular tests increase diagnostic yield and may confirm diagnosis when cytology is inconclusive.[10][35][36][37][38][39][40][41]

Fluid: Vitreous humor (primary), aqueous (adjunct/alternative)[10][42]

Common Biomarkers: MYD88 L265P mutation, IGH rearrangements, NGS lymphoma panels[36][37][38][39][40]

Clinical Use:[36][37][38][39][41][42]

- Diagnosis of vitreoretinal lymphoma; distinguish PIOL from uveitis

- Confirm diagnosis when cytology inconclusive

- Monitor therapeutic response and/or recurrence

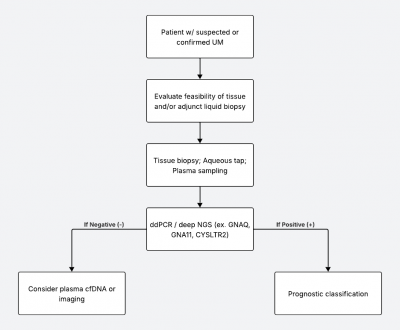

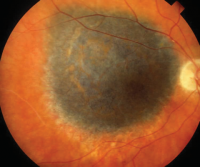

Uveal Melanoma (UM)

Fluid: Aqueous humor, vitreous, and plasma[20][21][22][44][45]

Mutations: GNAQ, GNA11, CYSLTR2, PLCB4, BAP1 (BRCA1 associated protein 1), SF3B1 (splicing factor 3b subunit 1), and EIF1AX (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1A X-linked) predict metastatic risk and are thus routinely targeted in molecular profiling and liquid biopsy approaches[21][22][45][46]

CNVs: Monosomy 3 and 8q gain strongly correlate with metastasis. 6p gain is also noted in molecular risk stratification[20][21][22][26][46]

Biomarkers: Methylation and microRNA signatures, as well as proteomic profiles from aqueous humor, are emerging as non-invasive biomarkers for risk stratification and disease monitoring[21][46][47]

Clinical Use:[20][45][47][48][49][50]

- Prognosis and metastatic risk assessment

- Detection of minimal residual disease

- Monitoring for metastatic recurrence

- Stratification for clinical trials

Comparative Summary

| Retinoblastoma | Uveal Melanoma | Primary Intraocular Lymphoma (PIOL) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred Fluid | Aqueous | Aqueous / Plasma | Vitreous |

| Common Genes | RB1, CNVs | GNAQ, GNA11, BAP1, SF3B1 | MYD88, IGH |

| Diagnostic Role | Primary diagnosis | Adjunct / prognosis | Primary diagnosis |

| Prognostic Role | Yes (chromosomal instability) | Yes (monosomy 3, 8q gain) | Limited |

| Monitoring Role | Response & relapse | Metastasis risk | Recurrence |

| Validation Level | High | Moderate | Moderate |

Challenges and Limitations[13][27][28]

Low analyte concentration: Limited sample volumes and variable shedding reduce sensitivity.

Technical variability: Differences in sampling, extraction, and sequencing workflows limit reproducibility.

Analytical noise: False positives from clonal hematopoiesis or sequencing artifacts.

Temporal dynamics: cfDNA levels fluctuate with treatment and tumor activity.

Clinical validation gap: Most studies remain small, retrospective, or single-center.

Cost and access: High assay costs and lack of standardized clinical-grade tests limit adoption.

Future Directions[13][28]

Standardization: Establish guidelines for ocular liquid biopsy collection, storage, and reporting.

Clinical Trials: Integrate cfDNA endpoints into ocular oncology trials to correlate with outcomes.

Multi-omic approaches: Combine genomic, methylation, and proteomic profiling for enhanced accuracy.

Artificial Intelligence: Apply machine learning to integrate cfDNA data with imaging and clinical metrics.

Point-of-care platforms: Develop cost-effective, rapid cfDNA tests suitable for ophthalmic clinics.

Summary and Key Takeaways

Liquid biopsy in ocular oncology enables minimally invasive molecular profiling of intraocular tumors. Aqueous and vitreous sampling combined with sensitive molecular assays (ddPCR, NGS, methylation profiling) has demonstrated diagnostic and prognostic value across retinoblastoma, uveal melanoma, and intraocular lymphoma. Integration of cfDNA, NGS, and methylation data into clinical workflows will enable earlier detection and tailored management. Future directions include standardization, AI integration, and real-time clinical application. The field is rapidly progressing toward integration of liquid biopsy into routine ocular oncology practice.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Kim ME, Xu L, Prabakar RK, et al. Aqueous Humor as a Liquid Biopsy for Retinoblastoma: Clear Corneal Paracentesis and Genomic Analysis. J Vis Exp. 2021;(175):62939. doi:10.3791/62939

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chigane D, Pandya D, Singh M, et al. Safety Assessment of Aqueous Humor Liquid Biopsy in Retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. Published online March 2025:S0161642025001800. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2025.03.018

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Choo CH, Pisitpayat P, Yan D, et al. Practice Patterns, Diagnostic Utility, and Safety of Anterior Chamber Paracentesis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025;277:260-268. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2025.05.017

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Berry JL, Pike S, Shah R, et al. Aqueous Humor Liquid Biopsy as a Companion Diagnostic for Retinoblastoma: Implications for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Options: Five Years of Progress. Am J Ophthalmol. 2024;263:188-205. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2023.11.020

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Mendes TB, Oliveira ID, Gamba FT, et al. Retinoblastoma: Molecular Evaluation of Tumor Samples, Aqueous Humor, and Peripheral Blood Using a Next-Generation Sequence Panel. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(8):3523. doi:10.3390/ijms26083523

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Cobrinik D. Retinoblastoma Origins and Destinations. Longo DL, ed. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(15):1408-1419. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1803083

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Xu L, Kim ME, Polski A, et al. Establishing the Clinical Utility of ctDNA Analysis for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment Monitoring of Retinoblastoma: The Aqueous Humor Liquid Biopsy. Cancers. 2021;13(6):1282. doi:10.3390/cancers13061282

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gerrish A, Mashayamombe-Wolfgarten C, Stone E, et al. Genetic Diagnosis of Retinoblastoma Using Aqueous Humour—Findings from an Extended Cohort. Cancers. 2024;16(8):1565. doi:10.3390/cancers16081565

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Wolf J, Chemudupati T, Kumar A, et al. Biobanking of Human Aqueous and Vitreous Liquid Biopsies for Molecular Analyses. J Vis Exp. 2023;(199):65804. doi:10.3791/65804

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Brown NA, Rao RC, Betz BL. Cell-Free DNA Extraction of Vitreous and Aqueous Humor Specimens for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Vitreoretinal Lymphoma. J Vis Exp. 2024;(203):65708. doi:10.3791/65708

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Martel A, Baillif S, Nahon-esteve S, et al. Liquid Biopsy for Solid Ophthalmic Malignancies: An Updated Review and Perspectives. Cancers. 2020;12(11):3284. doi:10.3390/cancers12113284

- ↑ Rowlands V, Rutkowski AJ, Meuser E, Carr TH, Harrington EA, Barrett JC. Optimisation of robust singleplex and multiplex droplet digital PCR assays for high confidence mutation detection in circulating tumour DNA. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12620. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49043-x

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Anitha K, Posinasetty B, Naveen Kumari K, et al. Liquid biopsy for precision diagnostics and therapeutics. Clin Chim Acta. 2024;554:117746. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2023.117746

- ↑ Mahuron KM, Fong Y. Applications of Liquid Biopsy for Surgical Patients With Cancer: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2024;159(1):96. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2023.5394

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Schmidt MJ, Prabakar RK, Pike S, et al. Simultaneous Copy Number Alteration and Single-Nucleotide Variation Analysis in Matched Aqueous Humor and Tumor Samples in Children with Retinoblastoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10):8606. doi:10.3390/ijms24108606

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Sato T, Montazeri K, Gragoudas ES, et al. Detection of Copy-Number Variation in Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Patients With Uveal Melanoma. JCO Precis Oncol. 2024;(8):e2300368. doi:10.1200/PO.23.00368

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kim ME, Polski A, Xu L, et al. Comprehensive Somatic Copy Number Analysis Using Aqueous Humor Liquid Biopsy for Retinoblastoma. Cancers. 2021;13(13):3340. doi:10.3390/cancers13133340

- ↑ Li HT, Xu L, Weisenberger DJ, et al. Characterizing DNA methylation signatures of retinoblastoma using aqueous humor liquid biopsy. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5523. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33248-2

- ↑ Ntzifa A, Lianidou E. Epigenetics and CTCs: New biomarkers and impact on tumor biology. In: International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. Vol 392. Elsevier; 2025:177-198. doi:10.1016/bs.ircmb.2024.03.002

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 De Bruyn DP, Van Poppelen NM, Brands T, et al. Evaluation of Circulating Tumor DNA as a Liquid Biomarker in Uveal Melanoma. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2024;65(2):11. doi:10.1167/iovs.65.2.11

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Im DH, Peng CC, Xu L, et al. Potential of Aqueous Humor as a Liquid Biopsy for Uveal Melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(11):6226. doi:10.3390/ijms23116226

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Barwinski N, Lever M, Rating P, et al. Presence of tumor DNA in aqueous humor is correlated with high risk uveal melanoma. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):19406. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-03915-7

- ↑ Smit KN, Van Poppelen NM, Vaarwater J, et al. Combined mutation and copy-number variation detection by targeted next-generation sequencing in uveal melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(5):763-771. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2017.187

- ↑ Gelmi MC, Bas Z, Malkani K, Ganguly A, Shields CL, Jager MJ. Adding the Cancer Genome Atlas Chromosome Classes to American Joint Committee on Cancer System Offers More Precise Prognostication in Uveal Melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(4):431-437. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.11.018

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Pašalić D, Nikuševa-Martić T, Sekovanić A, Kaštelan S. Genetic and Epigenetic Features of Uveal Melanoma—An Overview and Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12807. doi:10.3390/ijms241612807

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Soltysova A, Sedlackova T, Dvorska D, et al. Monosomy 3 Influences Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Gene Expression in Uveal Melanoma Patients; Consequences for Liquid Biopsy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9651. doi:10.3390/ijms21249651

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Nikanjam M, Kato S, Kurzrock R. Liquid biopsy: current technology and clinical applications. J Hematol OncolJ Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):131. doi:10.1186/s13045-022-01351-y

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Ho HY, Chung KS (Kasey), Kan CM, Wong SC (Cesar). Liquid Biopsy in the Clinical Management of Cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(16):8594. doi:10.3390/ijms25168594

- ↑ Gonzalez-Kozlova EE. Molecular Profiling of Liquid Biopsies for Precision Oncology. In: Laganà A, ed. Computational Methods for Precision Oncology. Vol 1361. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Springer International Publishing; 2022:235-247. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-91836-1_13

- ↑ Krebs MG, Malapelle U, André F, et al. Practical Considerations for the Use of Circulating Tumor DNA in the Treatment of Patients With Cancer: A Narrative Review. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(12):1830. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.4457

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retinoblastoma. https://www.aao.org/education/image/retinoblastoma-17. Accessed October 28, 2025.

- ↑ Jiménez I, Frouin É, Chicard M, et al. Molecular diagnosis of retinoblastoma by circulating tumor DNA analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:277-287. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.039

- ↑ Gao C, Patel J, Robbins M, et al. Detection and Characterization of RB1 Mosaicism in Patients With Retinoblastoma Receiving cfDNA Test. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2025;143(7):562. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2025.1079

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Primary intraocular lymphoma. https://www.aao.org/education/image/primary-intraocular-lymphoma. Accessed October 28, 2025.

- ↑ Takase H, Arai A, Iwasaki Y, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of vitreoretinal lymphoma – Clinical and basic approaches. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2022;90:101053. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101053

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Bonzheim I, Salmerón-Villalobos J, Süsskind D, et al. Molekulare Diagnostik des vitreoretinalen Lymphoms. Pathol. 2023;44(S3):150-154. doi:10.1007/s00292-023-01251-z

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Gu J, Jiang T, Liu S, et al. Cell-Free DNA Sequencing of Intraocular Fluid as Liquid Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Vitreoretinal Lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12:932674. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.932674

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Kwak JJ, Lee KS, Lee J, et al. Next-Generation Sequencing of Vitreoretinal Lymphoma by Vitreous Liquid Biopsy: Diagnostic Potential and Genotype/Phenotype Correlation. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2023;64(14):27. doi:10.1167/iovs.64.14.27

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Tan WJ, Wang MM, Castagnoli PR, Tang T, Chan ASY, Lim TS. Single B-Cell Genomic Analyses Differentiate Vitreoretinal Lymphoma from Chronic Inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(7):1079-1090. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.11.018

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Narasimhan S, Joshi M, Parameswaran S, et al. MYD88 L265P mutation in intraocular lymphoma: A potential diagnostic marker. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(10):2160. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1712_19

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Santos MC, Jiang A, Li AS, Rao PK, Wilson B, Harocopos GJ. Vitreoretinal Lymphoma: Optimizing Diagnostic Yield and Accuracy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;236:120-129. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.09.032

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Wang X, Su W, Gao Y, et al. A pilot study of the use of dynamic analysis of cell-free DNA from aqueous humor and vitreous fluid for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of vitreoretinal lymphomas. Haematologica. 2022;107(9):2154-2162. doi:10.3324/haematol.2021.279908

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Choroidal melanoma. https://www.aao.org/image/choroidal-melanoma-4 Accessed June 28, 2019.

- ↑ Pike SB, Reid MW, Peng CC, et al. Multicentre analysis of nucleic acid quantification using aqueous humour liquid biopsy in uveal melanoma: implications for clinical testing. Can J Ophthalmol. 2025;60(1):e23-e31. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2023.10.024

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Bustamante P, Tsering T, Coblentz J, et al. Circulating tumor DNA tracking through driver mutations as a liquid biopsy-based biomarker for uveal melanoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):196. doi:10.1186/s13046-021-01984-w

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Fuentes-Rodriguez A, Mitchell A, Guérin SL, Landreville S. Recent Advances in Molecular and Genetic Research on Uveal Melanoma. Cells. 2024;13(12):1023. doi:10.3390/cells13121023

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Peng CC, Sirivolu S, Pike S, et al. Diagnostic Aqueous Humor Proteome Predicts Metastatic Potential in Uveal Melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(7):6825. doi:10.3390/ijms24076825

- ↑ Zameer MZ, Jou E, Middleton M. The role of circulating tumor DNA in melanomas of the uveal tract. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1509968. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1509968

- ↑ Beasley AB, Chen FK, Isaacs TW, Gray ES. Future perspectives of uveal melanoma blood based biomarkers. Br J Cancer. 2022;126(11):1511-1528. doi:10.1038/s41416-022-01723-8

- ↑ Varela M, Villatoro S, Lorenzo D, Piulats JM, Caminal JM. Optimizing ctDNA: An Updated Review of a Promising Clinical Tool for the Management of Uveal Melanoma. Cancers. 2024;16(17):3053. doi:10.3390/cancers16173053