Ocular Manifestations of Mucolipidosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

The mucolipidoses (ML I–IV) are lysosomal storage disorders that disrupt intracellular degradation pathways and frequently present with characteristic ophthalmic findings. ML I is defined by a macular cherry-red spot and variable optic nerve atrophy, whereas ML II and III cause mild, typically non–vision-threatening corneal clouding. ML IV has the most severe ocular involvement, with early corneal clouding followed by progressive retinal dystrophy, cataract, strabismus, and eventual severe vision loss. Awareness of these distinct phenotypes, along with appropriate use of multimodal imaging and genetic testing, is essential for early diagnosis, counseling, and longitudinal ophthalmic management.

Disease Overview

The mucolipidoses (ML) are a group of inherited lysosomal storage disorders caused by defects in lysosomal enzyme trafficking or function resulting in intracellular accumulation of substrates including glycoproteins, glycolipids, and mucopolysaccharide-like material. The major subtypes are ML I (sialidosis), ML II (I-cell disease), ML III (pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy), and ML IV.

Pathophysiology

- ML I: Caused by mutations in the NEU1 gene encoding neuraminidase, leading to deficient removal of sialic acid residues from glycoproteins and oligosaccharides, which results in accumulation of sialylated compounds in lysosomes.[1]

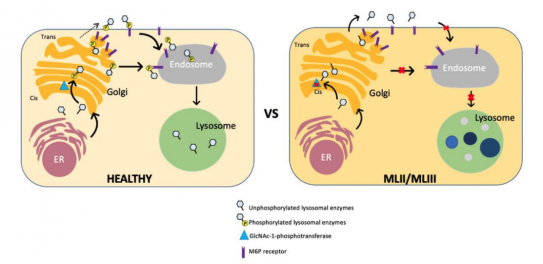

- ML II and ML III: Mutations in GNPTAB disrupt N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphotransferase (GlcNAc-1-phosphotransferase), the enzyme that normally tags lysosomal hydrolases with mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) for delivery into lysosomes. This causes lysosomal enzymes to be secreted outside the cell, with a shortage within lysosomes. Consequently, macromolecules (glycosaminoglycans, lipids, oligosaccharides) accumulate in lysosomes (Figure 1).[2]

- ML IV: Caused by mutations in the MCOLN1 gene encoding mucolipin-1 (TRPML1), a lysosomal membrane channel. Loss of TRPML1 impairs lysosomal trafficking and fusion, disrupts lipid and protein transport between lysosomes and endosomes, and leads to accumulation of lipids and other substrates within the lysosomes.[3]

When these substrates accumulate within ocular cells, the resulting lysosomal engorgement disrupts normal cell architecture and impairs key processes such as autophagy, mitochondrial turnover, membrane trafficking, and lysosomal calcium signaling. These failures lead to metabolic and oxidative stress and interference with normal homeostasis.

General Manifestations

ML I

ML I general findings: ataxia, hyperreflexia, dysarthria, and myoclonic epilepsy.[4][5]

Delayed growth rate, coarse facies, gingival hypertrophy, conductive hearing loss secondary to otitis media, thoracic deformities (e.g. kyphosis), mitral or aortic valve insufficiency, airway narrowing secondary thoracic cage stiffening, umbilical hernia, restriction of joint movements at the hips, knees, shoulders, and fingers.[6]

Features Unique to ML II

Onset is during early infancy, hydrops fetalis, low birth weight, clubfeet, hip dislocation, organomegaly, death typically occurs in early childhood.[6]

Features Unique to ML III

Onset is from late infancy to late childhood, normal birth weight, osteoporosis with pain, death typically occurs in early to middle adulthood.[6]

ML IV

Intellectual disability, developmental delay, loss of cognitive and motor skills, hypotonia, dysarthria, and spasticity.[3][7]

Ocular Manifestations

ML I

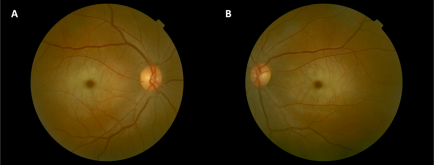

- Cherry-red spot (Figure 2), which presents as sudden, painless vision loss, are present in all patients.1 Patients may or may not have reduced visual acuity.[5][8]

- Patients may also develop nystagmus, optic nerve atrophy, and non-visual threatening lens opacities with a scattered white dots appearance. Just like cherry-red spots, the presence of optic nerve atrophy may or may not be associated with poor visual outcomes.[5][8]

ML II

- Patients present with mild corneal clouding that is not visually impairing, along with persistent epicanthal folds and mild proptosis.[6]

ML III

- Like ML II, ML also presents with corneal clouding and occasionally, mild proptosis as well.[6]

- One report also documented hyperopic astigmatism and retinal/optic nerve abnormalities (surface-wrinkling maculopathy, optic disc swelling, vascular tortuosity) as more rare findings, although retinal electrophysiologic testing and color vision were normal in the examined patients. Additionally, visual acuity did not deteriorate in the patients as they were followed over time up to 11 years.

ML IV

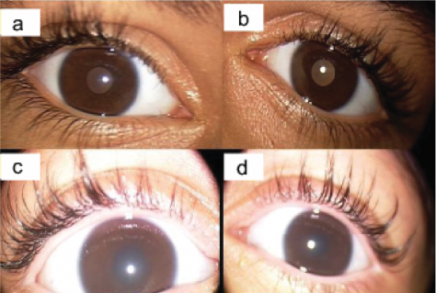

- ML IV ocular signs include strabismus (exotropia and esotropia), nystagmus, cataract, bone spicule retinal pigment epithelium changes, corneal clouding (Figure 3), retinal dystrophy, optic nerve atrophy, and ptosis.[9][10][11]

- Of note, corneal clouding is generally the earliest ocular manifestation. Over the first decade of life, retinal dystrophy occurs and eventually progresses to severe vision loss or legal blindness by the second decade.[7]

Evaluation

ML I

- Genetic testing confirming biallelic pathogenic variants in NEU1 is definitive for diagnosis.[4] Enzymatic assay demonstrating reduced neuraminidase activity in leukocytes or cultured fibroblasts is also used for diagnosis.[4][12]

- Electroencephalogram may show myoclonic seizure activity.[5] And MRI of the brain may show cerebellar, pontine, cerebral, and corpus callosum atrophy.[13]

- Importantly, increased urinary sialic acid excretion is not a constant finding among patients with ML I.[14]

- Fundoscopic examination may reveal macular cherry-red spots.[4] And Optical coherence tomography (OCT) may reveal optic nerve atrophy.[8]

ML II and II

- Genetic testing confirming biallelic pathogenic variants in GNPTAB is definitive for diagnosis. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry may be used to detect urinary free oligosaccharide species and glycosaminoglycans such as keratan sulfate.[6] Additionally, tandem mass spectrometry enzymatic activity assay can be used to detect increased lysosomal enzyme activity in serum.[15]

- Radiographic skeletal survey should be used to monitor changes in skeletal abnormalities and echocardiography to assess valve thickening and ventricular size and function.

- Hearing screen to check for evidence of conductive hearing loss.

- A baseline eye examination in patients can be helpful, although major visual impairment is not expected. For ML II specifically, an ophthalmologic evaluation is recommended between 6 and 12 months of age. Slit-lamp examination may demonstrate corneal clouding, and fundoscopic exam typically shows no retinal abnormalities.[6]

- Ophthalmologists should perform cycloplegic refraction to assess for presence of hyperopic astigmatism and utilize OCTs to detect papilledema and tortuous vessels (ML III).[16]

ML IV

- Genetic testing confirming biallelic pathogenic variants in MCOLN1 is definitive for diagnosis. Patients typically also have elevated plasma gastrin concentration secondary to achlorhydria.

- CBC may show anemia secondary to impaired iron absorption. Blood cystatin level may show elevation in patients with renal dysfunction.

- MRI findings may include corpus callosum hypoplasia, characterized by an absent rostrum and a dysplastic or absent splenium, along with white-matter signal abnormalities on T1-weighted imaging and increased ferritin deposition within the thalamus and basal ganglia. Cerebellar atrophy is often noted in older individuals.

- Electron microscopy: polymorphic lysosomal inclusions have been noted in conjunctival biopsy.[7]

- For strabismus and its subtypes, (exotropia and esotropia), ophthalmologists should perform the over-uncover test to identify tropias, the alternate cover test to detect phorias, and prism and alternate cover testing to measure the deviation.[17]

- Cataracts and corneal clouding can be identified via slit-lamp microscopy, and is more accurate than direct ophthalmoscopy.[18]

- Multimodal imaging combining spectral-domain OCT with fundus autofluorescence provides the most comprehensive diagnostic assessment of retinal changes.[19]

Management

ML I

- Valproic acid, levetiracetam, zonisamide, topiramate, lamotrigine, and lacosamide may be used for myoclonic seizures.[20]

- Gene therapy has shown promise in mouse models. Adeno-Associated Virus-mediated gene therapy co-delivering NEU1 and its chaperone protective protein/cathepsin A has demonstrated restoration of NEU1 activity in multiple tissues including brain, reversal of lysosomal storage, and normalization of neuroinflammation.[21]

- There is currently no ocular-directed management for ML type I.

ML II and III

- Restriction of joint movements: no measures are effective.

- Cognitive impairment can be supported through occupational therapy that uses interactive, stimulating activities to improve alertness, imitation abilities, and motivation.

- Gingival hyperplasia: gingivectomy can successfully treat mouth pain, infections, and abscesses.

- Due to airway narrowing, a smaller-than-standard endotracheal tube is recommended compared with what is normally used for children of the same age and size.

- Osteoporosis with pain (ML III): bisphosphonates may decrease pain and improve mobility.

- Since the corneal clouding and proptosis in affected individuals are mild and generally does not affect one’s vision, no ophthalmologic intervention is necessary.6

- No specific ocular interventions have been assessed for hyperopic astigmatism, maculopathy, optic disc swelling, vascular tortuosity (ML III). Given that the visual acuity in affected patients remained stable over time, it appears that only long-term observation is necessary.[16]

ML IV

- Iron deficiency anemia: oral ferrous sulfate.

- Kidney failure: refer to nephrologist for supportive care.

- Hypotonia and spasticity: physical therapy, rehabilitation, Botox injection (for spasticity).

- Feeding issues: feeding therapy and/or gastrostomy tube placement.

- Ocular irritation: topical lubricating eye drops, artificial tears, gels, or ointments.

- Strabismus: surgical correction.

- Corneal transplantation has not been successful because the donor corneal epithelium is eventually replaced by the abnormal host epithelium.[7]

- Unfortunately, patients will experience gradual vision loss, with no current treatment to reverse it.

References

- ↑ Strovel ET, Cusmano-Ozog K, Wood T, Yu C. Measurement of lysosomal enzyme activities: A technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genetics in Medicine. 2022;24(4):769-783. doi:10.1016/j.gim.2021.12.013

- ↑ Khan SA, Tomatsu SC. Mucolipidoses Overview: Past, Present, and Future. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6812. doi:10.3390/ijms21186812

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Misko A, Wood L, Kiselyov K, Slaugenhaupt S, Grishchuk Y. Progress in elucidating pathophysiology of mucolipidosis IV. Neurosci Lett. 2021;755:135944. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135944

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Riboldi GM, Martone J, Rizzo JR, Hudson TE, Rucker JC, Frucht SJ. Looking “Cherry Red Spot Myoclonus” in the Eyes: Clinical Phenotype, Treatment Response, and Eye Movements in Sialidosis Type 1. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements. 2021;11(1). doi:10.5334/tohm.652

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Sobral I, Cachulo M da L, Figueira J, Silva R. Sialidosis type I: ophthalmological findings. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014205871. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-205871

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Leroy JG, Cathey SS, Friez MJ. GNPTAB-Related Disorders. In: Adam MP, Bick S, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. Accessed December 6, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1828/

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Misko A, Grishchuk Y, Goldin E, Schiffmann R. Mucolipidosis IV. In: Adam MP, Bick S, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. Accessed December 6, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1214/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Daich Varela M, Zein WM, Toro C, et al. A sialidosis type I cohort and a quantitative approach to multimodal ophthalmic imaging of the macular cherry-red spot. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(6):838-843. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316826

- ↑ Smith JA, Chan CC, Goldin E, Schiffmann R. Noninvasive diagnosis and ophthalmic features of mucolipidosis type IV. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(3):588-594. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00968-X

- ↑ Smith JA, Chan CC, Goldin E, Schiffmann R. Noninvasive diagnosis and ophthalmic features of mucolipidosis type IV. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(3):588-594. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00968-X

- ↑ Gibson D, Brar V, Li R, Kalra A, Goodwin A, Couser N. The High Association of Ophthalmic Manifestations in Individuals With Mucolipidosis Type IV. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2022;59(5):332-337. doi:10.3928/01913913-20211206-03

- ↑ Castilhos CD, Mello AS, Burin MG, et al. Application of a protocol for the detection of disorders of sialic acid metabolism to 124 high-risk Brazilian patients. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2003;119A(3):348-351. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20203

- ↑ Sialidosis. MedLink Neurology. Accessed December 9, 2025. https://www.medlink.com/articles/sialidosis

- ↑ Mütze U, Bürger F, Hoffmann J, et al. Multigene panel next generation sequencing in a patient with cherry red macular spot: Identification of two novel mutations in NEU1 gene causing sialidosis type I associated with mild to unspecific biochemical and enzymatic findings. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports. 2017;10:1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ymgmr.2016.11.004

- ↑ Hong X, Pollard L, He M, Gelb MH, Wood TC. Multiplex tandem mass spectrometry enzymatic activity assay for the screening and diagnosis of Mucolipidosis type II and III. Mol Genet Metab Rep. 2023;35:100978. doi:10.1016/j.ymgmr.2023.100978

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Traboulsi EI, Maurhenee IH. Ophthalmologic findings in mucolipidosis III (pseudo-hurler polydystrophy). American journal of ophthalmology. 1986;102(5):592-597. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(86)90529-5

- ↑ Sprunger DT, Lambert SR, Hercinovic A, et al. PEDIATRIC OPHTHALMOLOGY/STRABISMUS PREFERRED PRACTICE PATTERN DEVELOPMENT PROCESS AND PARTICIPANTS. Ophthalmology. 2023;130(3):P179-P221. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.11.002

- ↑ Chen SP, Woreta F, Chang DF. Cataracts: A Review. JAMA. 2025;333(23):2093-2103. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.1597

- ↑ Schuerch K, Marsiglia M, Lee W, Tsang SH, Sparrow JR. Multimodal Imaging of Disease-Associated Pigmentary Changes in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Retina. 2016;36(Suppl 1):S147-S158. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001256

- ↑ Kanner AM, Bicchi MM. Antiseizure Medications for Adults With Epilepsy: A Review. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1269-1281. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3880

- ↑ van de Vlekkert D, Hu H, Weesner JA, et al. AAV-mediated gene therapy for sialidosis. Mol Ther. 2024;32(7):2094-2112. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.05.029