Ocular Venous Air Embolism

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Definition

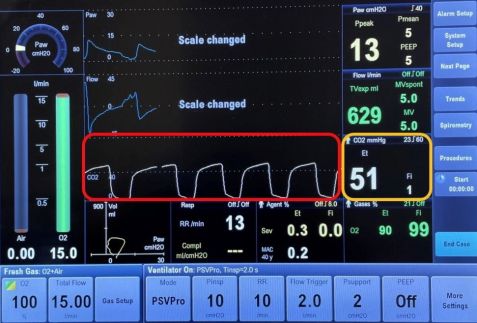

Ocular venous air embolism (OVAE) or Presumed air by vitrectomy embolisation (PAVE) is a rare, but often fatal complication of ocular surgery. It is defined as the entry of air into the systemic venous circulation through the ocular venous circulation from a choroidal detachment or wound. This air eventually reaches the right ventricular outflow tract, causing impaired gas exchange in the lungs. This results in a sudden drop in end-tidal carbon dioxide (the level of carbon dioxide released in an exhaled breath, Figure 1), followed by signs of cardiovascular collapse during vitrectomy air infusion.[1]

Pathophysiology

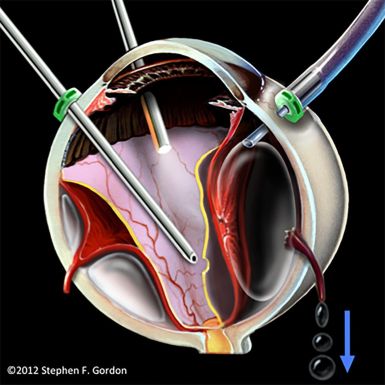

The OVAE is caused by an improperly positioned infusion line during vitrectomy, leading to the entry of pressurized air into the suprachoroidal space. This results in the tearing of vortex veins, allowing for air to be transmitted from the suprachoroidal space into the systemic venous circulation (Figure 2).[2]

From the suprachoroidal space, the air can travel down the following pathway: vortex veins, ophthalmic veins, cavernous sinus, jugular veins, and eventually into the right atrium and ventricle. [3] Apart from vitrectomy, OVAE can also occur when air from the vitreous cavity enters intact vortex veins through large choroidal wounds which can occur secondary to trauma or choroidal melanoma resection.[2]

Risk Factors[4]

a. Pars plana vitrectomy: slippage of the air infusion cannula can cause suprachoroidal infusion of pressurized air.[4] This is more likely to occur in transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy as compared to 20-gauge vitrectomy with sutured infusion cannula.

b. Large choroidal wounds secondary to trauma.

c. Choroidal melanoma resection.

Diagnosis

The first clue to OVAE is a sudden drop in end-tidal carbon dioxide, which occurs when the air bubbles travel through the venous circulation to the right ventricular outflow tract, leading to impaired pulmonary gas exchange. End-tidal carbon dioxide is a measure of the level of carbon dioxide found at the end of an exhaled breath. It reflects how well carbon dioxide is removed from the blood and exhaled from the lungs. When there is pulmonary thromboembolism, there is a creation of dead space or areas in the lung where there is air without adequate blood flow. This leads to a decrease in end-tidal carbon dioxide. In OVAE, the drop in end-tidal carbon dioxide precedes oxygen desaturation and systemic hypotension.[5] [6] Within minutes, other signs follow, such as cardiac dysrhythmias and a ”mill-wheel” cardiac murmur.[5] Cephalic cyanosis, or persistent blue discoloration of the head, has been documented in at least one case of OVAE.[1]

Prognosis

When large amounts of air enter the blood stream, the right ventricular outflow tract can become blocked. This results in impaired gas exchange in the lungs, which leads to decreased cardiac output, and secondary pulmonary hypertension, followed by systemic hypotension. This can lead to death within one minute.[2] Due to the pressurized infusion of air and the proximity of the eye to the heart, OVAE may be the most lethal of all forms of iatrogenic surgical venous air embolism (VAE).[2] Of the thirteen reported cases in the literature to date, 9 of 13 cases (69%) were fatal.[4] Of the nine fatalities, five patients died in the operating room, three others died on the same day of the event, and one patient died four weeks after the event due to multiple organ failure, despite extensive medical supportive measures.[2] Of the four patients who survived OVAE, a drop in end-tidal carbon dioxide was noted in all cases and air infusion was terminated. Appropriate medical supportive measures were applied, and only one of the four cases required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).[2] Detailed summaries of each of the cases can be found in a review published by Morris et al.[2]

Prevention

Because of how lethal OVAE is, management begins with awareness and prevention. In pars plana vitrectomy, for example, intraoperative timeouts are important to ensure that the infusion cannula is properly placed prior to starting fluid-gas exchange.[5] It is important to ensure that the proper position is maintained throughout the fluid-gas exchange.[7] Prior to gas infusion, the surgeon should ensure that the concentration of the gas is correct.[3] Using a secured infusion cannula during combined vitrectomy and scleral buckle cases has also been recommended.[4] If during vitrectomy surgery, a progressive choroidal detachment begins to occur, the surgeon should immediately stop air or gas infusion. During procedures such as trauma repair with uveal prolapse or resection of a choroidal mass, these steps are even more critical.[7] During these high-risk cases, the use of a precordial doppler monitor may be beneficial, in addition to alerting the anesthesia team during air infusion.[7]

Treatment

If VAE is suspected, the gas infusion should be terminated immediately. Supplemental oxygen (100%) should be applied.[7] The patient should be placed in the Trendelenburg position, which keeps the air within the ventricle of the heart and reduces the amount of air that enters the pulmonary circulation. Closed-chest cardiac massage, which is the application of forceful pressure on the lower sternum, may help to force air out of the pulmonary outflow tract to improve blood flow.8 Vasopressors and cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be necessary.[8] If indicated, the patient should be transferred to a hospital with ECMO capabilities, which can be lifesaving.[7]

Perfluorocarbon syndrome

Definition

Perfluorocarbon syndrome is defined as the delayed postoperative gas embolism derived from perfluorocarbon liquid (PFCL) due to its high vapor pressure at body temperature.

Pathophysiology

During high risk vitreoretinal surgeries that may compromise the integrity of choroidal vasculature, PFCL used during these surgeries may egress into the systemic vasculature. As the body temperature is higher than the intraoperative intravitreal temperature, PFCL transitions to its gaseous form.[9] PFCL has a lower permeability through alveolar-capillary barrier and consequently blocks the pulmonary circulation leading to an impaired pulmonary gas exchange.[9] This can further lead to hypoxemia, respiratory failure, even death.

Risk factors

a. Pars plana vitrectomy: endoresection of uveal tumor, large retinectomy

b. PFCL use during surgery

Diagnosis

Diagnosis should be suspected if a patient develops hypoxemia several hours after vitreoretinal surgery in which choroidal vasculature may have been accessed and PFCL was used. Since perfluorocarbon syndrome typically manifests several hours after the surgery, it is possible that patients may have already left the hospital setting, therefore the first symptoms reported by patients may be dyspnea. Clinical signs would be similar to those of air or gas embolism, such as hypoxemia, low end-tidal CO2, reduced arterial blood oxygen saturation, hypotension, and potential cardiac arrest.[10] Diagnostic work up includes CT angiography which may show pulmonary air embolism[11] and transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography which may show ventricular dilation[12] and air embolism.

Prevention and treatment

Higher vapor pressure of PFCL imposes greater risk of gas embolism.[9] Perfluorodecalin may be considered as the vapor pressure of PFD is 13.6 mmHg at 37°C, whereas the vapor pressure of perfluoro-n-octane (PFO) is 50-55 mmHg at 37°C.[13] Any vortex veins that are exposed should be cauterized. When perfluorocarbon syndrome is suspected, cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be given. If indicated, ECMO should be initiated as soon as possible.[12][14]

Prognosis

Only one proven[12] and three possible perfluorocarbon syndrome cases[11][14] have been reported in the literature. Out of the four patients, two patients who received ECMO survived[12][14], while the other two died before any treatment could have been given.[11][14]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Morris RE, Boyd GL, Sapp MR, Oltmanns MH, Kuhn F, Albin MS. Ocular Venous Air Embolism: A Report of 5 Cases. Journal of VitreoRetinal Diseases. 2019;3(2):107-110. doi:10.1177/2474126418819058

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Morris RE, Boyd GL, Sapp MR, Oltmanns MH, Kuhn F, Albin MS. Ocular Venous Air Embolism (OVAE): A Review. Journal of VitreoRetinal Diseases. 2019;3(2):99-106. doi:10.1177/2474126418822892

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Morris RE, Sapp MR, Oltmanns MH, Kuhn F. Presumed Air by Vitrectomy Embolisation (PAVE) a potentially fatal syndrome. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2014;98(6):765-768. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303367

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Dumas G, Morris R. Ocular venous air embolism: An unappreciated lethal complication. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2020;66:109935. doi:10.1016/J.JCLINANE.2020.109935

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Lim LT, Somerville GM, Walker JD. SMALL CASE SERIES Venous Air Embolism During Air/Fluid Exchange: A Potentially Fatal Complication.; 2010. https://jamanetwork.com/

- ↑ Gayer S, Palte HD, Albini TA, et al. In Vivo Porcine Model of Venous Air Embolism During Pars Plana Vitrectomy. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;171:139-144. doi:10.1016/J.AJO.2016.06.027

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Bothma P, Rajapakse D. Ocular venous air embolism: An unappreciated lethal complication. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2021;74:110384. doi:10.1016/J.JCLINANE.2021.110384

- ↑ Palmon SC, Moore LE, Lundberg J, Toung T. Venous air embolism: A review. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 1997;9(3):251-257. doi:10.1016/S0952-8180(97)00024-X

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Sass DJ, Van Dyke RA, Wood EH, Johnson SA, Didisheim P. Gas embolism due to intravenous FC 80 liquid fluorocarbon. J Appl Physiol. 1976 May;40(5):745-51. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.5.745. PMID: 931904.

- ↑ Kasi SK, Grant S, Flynn HW, Albini TA, Relhan N, Heier J, et al. Venous air embolism during pars plana vitrectomy: a case report and review of the literature. J Vitreoretina Dis. 2017;1:334-7

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Ruschen H, Romano MR, Ferrara M, Loh GK, Wickham L, Damato BE, da Cruz L. Perfluorocarbon syndrome-a possible, overlooked source of fatal gas embolism following uveal-melanoma endoresection. Eye (Lond). 2022 Dec;36(12):2348-2349. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02021-6. Epub 2022 Mar 28. PMID: 35352011; PMCID: PMC9674629.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Voegtlin O, Tadini E, Milliet N, Guyot R, Wolfensberger T, Augsburger M, Chiche JD. Near-fatal perfluorocarbon-induced gas embolism after complex vitreoretinal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2025 Jul;135(1):223-225. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2025.03.021. Epub 2025 Apr 23. PMID: 40274511; PMCID: PMC12597451.

- ↑ Dias AMA, Caco AI, Coutinho JAP, Santos LMNBF, Pineiro MM, Vega LF, et al. Thermodynamic properties of perfluoro-n-octane. Fluid Phase Equilibria. 2004;225:39-47

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Rojanaporn D, Tipsuriyaporn B, Chulalaksiriboon P, Virankabutra T, Morakul S, Damato B. Fatal Air Embolism after Choroidal Melanoma Endoresection without Air Infusion: A Case Report. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2021 Oct;7(5):321-325. doi: 10.1159/000518976. Epub 2021 Aug 13. PMID: 34722487; PMCID: PMC8531826.