Ophthalmological Features of Nipah Virus

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Nipah virus is an emerging zoonotic infection that can cause severe encephalitis and, in a subset of survivors, delayed ocular and neuro-ophthalmic complications. Reported findings include cranial nerve palsies, Horner syndrome, photophobia, and branch retinal artery occlusion, most likely driven by viral small-vessel vasculitis. Enhanced recognition of these signs by ophthalmologists can help ensure timely diagnosis and vigilant follow-up for patients during and after outbreaks.

Disease and Etiology

- Nipah virus (NiV) is a member of the Henipavirus genus within the family Paramyxoviridae. The virus is enveloped, negative-sense, and single-stranded.[1]

- The virus was first identified in 1998 during an outbreak in Sungai Nipah, Malaysia, and has since been responsible for multiple outbreaks across South and Southeast Asia,[2] with recent outbreaks occurring in India during 2025.[3]

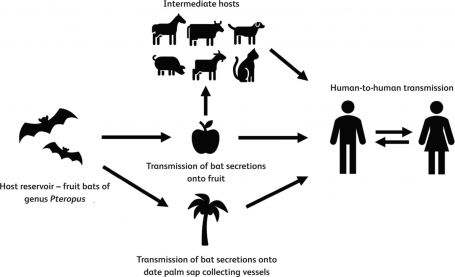

- Fruit bats of the genus Pteropus (Figure 1) serve as the natural reservoir, capable of transmitting NiV to humans or intermediate hosts such as pigs. These bats are widely distributed across Southeast Asia, the South Pacific, and Australia.[4]

- Human infection can occur through ingestion of contaminated food (especially fruits and date palm sap contaminated with the bat’s bodily fluids), exposure to infected animals or their secretions, or person-to-person transmission via droplets or aerosols (Figure 2).[5]

Pathophysiology

Initial viral replication occurs in the respiratory epithelium, where NiV efficiently infects airway epithelial cells. Once replication is established, the virus breaches the epithelial barrier and disseminates systemically. NiV enters cells through two envelope glycoproteins. The first is glycoprotein G, which binds to the host receptors ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3. The second is glycoprotein F, which mediates pH-independent membrane fusion. Ephrin-B2 is highly expressed on endothelial cells, smooth muscle-associated vasculature, airway epithelium, and neurons, while ephrin-B3 is enriched in the central nervous system (CNS). This receptor distribution explains the virus’s systemic nature of infection. Following attachment, G-ephrin interactions trigger F-protein activation, enabling fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane.[6]

Regarding CNS infection, there have been two proposed mechanisms:

- Hematogenous spread, where infected endothelial cells and leukocyte trafficking allow the virus to cross the blood-brain barrier, leading to parenchymal infection.[6]

- Olfactory neuronal spread, in which infection of the nasal olfactory mucosa enables anterograde movement along the olfactory nerve into the olfactory bulb.[6]

Symptoms

- In the first 2 weeks, patients may experience fever, headaches, cough, sore throat, dyspnea, and vomiting.[4]

- Initial symptoms may later be followed by neurological signs such as disorientation, confusion, drowsiness, coma, seizures, myoclonus, areflexia, hypotonia, and signs of cerebellar dysfunction.[4][5]

- Ocular symptoms are not as well-studied, but reports have documented blurry vision, double vision, transient blindness, Horner’s syndrome, nystagmus, oculomotor palsies, pupillary abnormalities, and branch retinal artery occlusion.[6]

Ocular Manifestations

In an analysis of 94 patients infected with Nipah virus in an outbreak in Malaysia between September 1998 and June 1999:

- Over half (55%) exhibited depressed consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale <15), and this group commonly demonstrated brainstem deficits such as abnormal doll’s-eye reflexes and pinpoint pupils with variable reactivity.[7]

- Abnormal doll’s-eye reflexes and pinpoint pupils correlated strongly with poor outcomes. An abnormal doll’s-eye reflex was present in 87% of patients who died. Similarly, pinpoint pupils were present in 97% of fatal cases.[7]

- Four patients developed delayed neurologic manifestations, with onset of neurologic symptoms ranging from 2 weeks to 11 weeks. One patient developed oculomotor nerve palsy in this period, which she successfully recovered from.[7]

From a study involving 22 affected subjects across Malaysia and Singapore:

- One individual developed left-sided Horner syndrome nine months following infection, presenting with drooping of the eyelid, a constricted pupil, and loss of sweating on the affected side of the forehead. Electrophysiologic testing revealed C8-T1 denervation, and MRI identified a small lesion at the C7 spinal cord level.[8]

- An abducens nerve palsy resulted in ongoing diplopia in one patient.

- Another patient had persistent nystagmus.

- One patient developed unilateral blurred vision one month after hospital discharge. Ophthalmic evaluation showed a branch retinal artery occlusion, confirmed with fluorescein angiography.[8]

Another study performed neurological evaluations on 22 survivors of Nipah virus infection and revealed the following:

- Two survivors experienced photophobia, lasting anywhere from a few days to two months.

- Delayed cranial neuropathies were documented in four individuals, including two cases of third-nerve palsy and one case of sixth-nerve palsy. These deficits emerged months to a year after the initial infection.[9]

Nipah virus-related ocular findings are believed to result from small-vessel vasculitis that damages the vascular endothelium, leading to thrombosis, ischemia, and microinfarction within ocular and visual pathways. Histologic studies show endothelial necrosis, inflammatory infiltrates, and syncytial endothelial cells in affected vessels, reflecting direct viral cytopathic effects.[10]

Ophthalmic Evaluation

Cranial Nerve III Palsy

- Cranial nerve III (CN3) palsy has been documented in Nipah Virus infection.[7] CN 3 innervates the medial rectus, superior rectus, inferior rectus, inferior oblique, levator palpebrae, and sphincter pupillae. Injury would thus result in ptosis, a dilated and non-reactive pupil, impaired eye adduction, and elevation.

- To evaluate, ask patients to gaze in an “H” pattern without moving their head to isolate each muscle’s function. Perform a penlight examination to assess for pupillary responses.

Cranial Nerve VI Palsy

- Cranial nerve VI (CN 6) palsy has also been implicated in Nipah Virus.[8] CN 6 innervates the lateral rectus muscle; inability to abduct the eye indicates VI palsy. Horizontal diplopia that worsens when looking toward the affected side is characteristic.

- To evaluate, ask the patient to look laterally (outward) with each eye.

Abnormal Doll’s Eye Reflex

- As noted earlier, an abnormal doll’s-eye reflex was present in 87% of patients who died, underscoring its importance as a critical neurologic sign in Nipah virus infection.[7]

- Normally, the eyes move conjugately in the opposite direction of passive head movement. If there is significant brainstem damage, this natural movement may be impaired.

- This can be evaluated as part of a broader ophthalmologic bedside examination.

Horner Syndrome

- Horner syndrome has also been reported in Nipah virus infection and is characterized by ipsilateral ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis.[8]

- The American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria mentioned MRI head without and with IV contrast and MRA head and heck without and with IV contrast as an excellent method to assess for Horner’s Syndrome secondary to inflammation, infection, or small vessel ischemia.[11]

Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion

- Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion (BRAO) was also reported in Nipah virus infection.[8] BRAO typically presents as acute, painless, partial monocular visual loss.

- Diagnosis is confirmed by funduscopic findings of segmental retinal whitening and arterial attenuation in the affected branch, sometimes with visible emboli, and can be supported by optical coherence tomography or fluorescein angiography.[12]

Diagnosis

- The gold standard test for Nipah virus is through real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from throat and nasal swabs, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, or blood.

- An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be used to detect antibodies produced against Nipah virus. IgM antibodies can be detected starting the first week after symptom onset, peaking at 9 days, and persisting for 3 months. IgG antibodies can be detected after the second week of illness, persisting for over 8 months.[13]

Laboratory Tests

- Complete blood count (CBC) often shows thrombocytopenia and leukopenia.

- Liver panel may reveal elevated liver enzymes.

- Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) may reveal elevated white blood cell count and protein.[5]

Imaging Studies

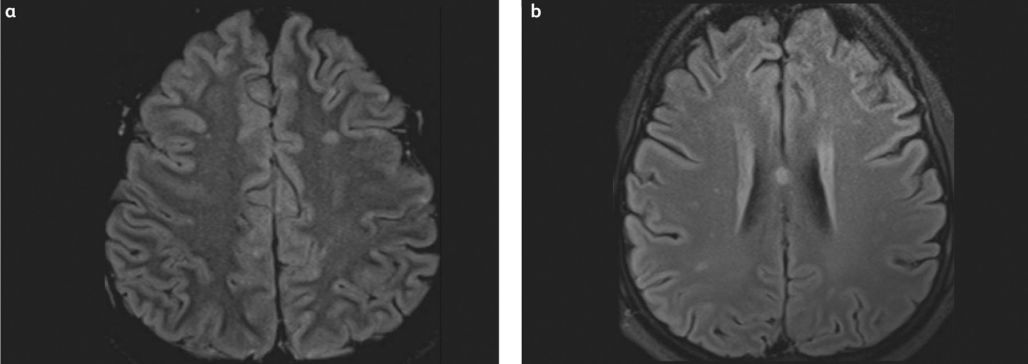

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically reveals multiple small (2 to 7 mm) hyperintense lesions (Figure 3) on T2-weighted images, most commonly located in the subcortical and deep white matter, periventricular regions, and corpus callosum.[5][14]

Treatment

- Currently there are no licensed treatments available for Nipah virus, including treatment tailored to ocular manifestations. While ocular symptoms have been reported in outbreaks, there was no mention of tested pharmacotherapy for the eye specifically.

- Generally, treatment is limited to supportive care, including rest, and hydration.

- m102.4, a monoclonal antibody that neutralizes Nipah viruses, has completed phase 1 clinical trials, although its safety has not been systematically assessed.[15]

- The drug remdesivir demonstrated benefits among exposed nonhuman primates, in which the exposed primates only developed mild respiratory symptoms over the course of 3 months post-infection. The control group, in contrast, developed severe respiratory failure and did not survive the infection.[16][17] Remdesivir may complement immunotherapeutic treatments like m102.4.

- Ribavirin was used to treat a small number of patients in the 1999 Malaysian Nipah outbreak, but its efficacy is unclear.[4] Two animal studies revealed that ribavirin does not prevent but may delay death up to 5 days.[18][19] One human study highlighted that ribavirin reduced mortality rate by 36% while another revealed no benefit.[7][20]

Vaccination

- There is currently no licensed vaccine for Nipah virus in humans, but several candidates are in advanced development and early-phase clinical trials.

- The most advanced candidate is the recombinant soluble Hendra virus G glycoprotein vaccine (HeV-sG-V), which has shown a favorable safety profile and robust immunogenicity in a recent phase 1 trial. Two doses of HeV-sG-V, 28 days apart, induced high neutralizing antibody titers against both Nipah Bangladesh and Malaysia strains, with no serious adverse events reported.[21]

Prevention

In the absence of a vaccine, the most effective strategy to limit Nipah virus infection is proactive education about exposure risks and protective behaviors.[22]

Public health educational messages should focus on:

Reducing bat-to-human exposure:

Mitigation should begin with preventing contamination of food products by fruit bats. Covering date palm sap collection sites, boiling fresh sap before consumption, and thoroughly washing and peeling fruit can decrease the chance of viral transmission. Any fruit showing evidence of bat bites should be discarded.

Reducing animal-to-human exposure:

Individuals in close contact with livestock, especially pigs, should use gloves and protective clothing when handling sick animals or during slaughtering operations. In areas where Nipah is known to circulate, pig farms should minimize bat access to animal feed and housing structures.

Reducing person-to-person transmission:

Limiting direct unprotected contact with infected individuals is essential. Frequent hand hygiene and appropriate precautions when caring for symptomatic patients can help prevent spread in community and healthcare settings.

References

- ↑ Venkatesh A, Patel R, Goyal S, Rajaratnam T, Sharma A, Hossain P. Ocular manifestations of emerging viral diseases. Eye (Lond). 2021;35(4):1117-1139. doi:10.1038/s41433-020-01376-y

- ↑ Blyden K, Thomas J, Emami-Naeini P, et al. Emerging Infectious Diseases and the Eye: Ophthalmic Manifestations, Pathogenesis, and One Health Perspectives. International Ophthalmology Clinics. 2024;64(4):39. doi:10.1097/IIO.0000000000000539

- ↑ Nipah Virus Infection - India. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON577

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 CDC. Nipah virus: Facts for Clinicians. Nipah Virus. April 18, 2024. Accessed December 1, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nipah-virus/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Rathish B, Vaishnani K. Nipah Virus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed December 1, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570576/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Devnath P, Wajed S, Chandra Das R, Kar S, Islam I, Masud HMAA. The pathogenesis of Nipah virus: A review. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2022;170:105693. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105693

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Goh KJ, Tan CT, Chew NK, et al. Clinical Features of Nipah Virus Encephalitis among Pig Farmers in Malaysia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(17):1229-1235. doi:10.1056/NEJM200004273421701

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Lim CCT, Lee WL, Leo YS, et al. Late clinical and magnetic resonance imaging follow up of Nipah virus infection. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2003;74(1):131-133. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.1.131

- ↑ Sejvar JJ, Hossain J, Saha SK, et al. Long-term neurological and functional outcome in Nipah virus infection. Annals of Neurology. 2007;62(3):235-242. doi:10.1002/ana.21178

- ↑ Chua KB, Goh KJ, Wong KT, et al. Fatal encephalitis due to Nipah virus among pig-farmers in Malaysia. The Lancet. 1999;354(9186):1257-1259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04299-3

- ↑ Dubey P, Shekhrajka N, Juliano AF, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Horner Syndrome. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2025;22(11):S550-S577. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2025.08.041

- ↑ Scott IU, Campochiaro PA, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Retinal Vascular Occlusions. Lancet. 2020;396(10266):1927-1940. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31559-2

- ↑ Levine CB, Sauer LM, McLellan SLF, et al. Nipah virus: a summary for clinicians. Int J Emerg Med. 2025;18(1):126. doi:10.1186/s12245-025-00916-1

- ↑ Alam AM. Nipah virus, an emerging zoonotic disease causing fatal encephalitis. Clin Med (Lond). 2022;22(4):348-352. doi:10.7861/clinmed.2022-0166

- ↑ Playford EG, Munro T, Mahler SM, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity of a human monoclonal antibody targeting the G glycoprotein of henipaviruses in healthy adults: a first-in-human, randomised, controlled, phase 1 study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(4):445-454. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30634-6

- ↑ de Wit E, Williamson BN, Feldmann F, et al. Late remdesivir treatment initiation partially protects African green monkeys from lethal Nipah virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2023;216:105658. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2023.105658

- ↑ Lo MK, Feldmann F, Gary JM, et al. Remdesivir (GS-5734) protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(494):eaau9242. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9242

- ↑ Freiberg AN, Worthy MN, Lee B, Holbrook MR. Combined chloroquine and ribavirin treatment does not prevent death in a hamster model of Nipah and Hendra virus infection. Journal of General Virology. 2010;91(3):765-772. doi:10.1099/vir.0.017269-0

- ↑ Georges-Courbot MC, Contamin H, Faure C, et al. Poly(I)-Poly(C12U) but Not Ribavirin Prevents Death in a Hamster Model of Nipah Virus Infection. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2006;50(5):1768-1772. doi:10.1128/aac.50.5.1768-1772.2006

- ↑ Chong HT, Kamarulzaman A, Tan CT, et al. Treatment of acute Nipah encephalitis with ribavirin. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(6):810-813. doi:10.1002/ana.1062

- ↑ Frenck RW, Naficy A, Feser J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a Nipah virus vaccine (HeV-sG-V) in adults: a single-centre, randomised, observer-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 study. Lancet. Published online November 14, 2025:S0140-6736(25)01390-X. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01390-X

- ↑ World Health Organization. Nipah virus. Who.int. Published May 30, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nipah-virus