Pediatric Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD) is a demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system characterized by the presence of MOG antibodies. In children, MOGAD has a wide clinical phenotype, and MOG antibody testing should be considered in all cases of pediatric CNS demyelinating disease.[1] Establishing the diagnosis is critical for counseling patients and their families about relapse risk and available treatments. This article highlights the distinct features of pediatric MOGAD rather than providing a general summary of MOGAD, which has been described elsewhere. Pediatric MOGAD is notably more heterogeneous than the adult form, with the differing features of pediatric disease accentuated in younger patients..

Epidemiology

The incidence of MOGAD is higher in children than in adults, with a recent study in the Dutch population demonstrating an incidence of 0.31/100,000 of MOG positive acute demyelinating syndromes (ADS) in children compared with 0.13/100,000 in adults.[2] It is estimated that 50% of all MOGAD cases occur in children.[3] [4] As with adults, there does not appear to be a sex-bias with MOGAD with the female-to-male ratio being approximately 1:1.[5] [6]

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation

The most common initial presentation of pediatric MOGAD is acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), accounting for approximately 40–50% of cases.[7] [8] [9] In contrast, adults most frequently present with optic neuritis (ON), while ADEM occurs as a presenting feature in only ~10–15% of cases.[5] The predominance of ADEM in children is particularly evident in those younger than 11 years, whereas older children (>11 years) exhibit a clinical profile more similar to adults, with ADEM representing only about 13% of first attacks.[10] Notably, this age-related difference in presentation extends to recurrences: younger patients who initially present with ADEM are more likely to experience subsequent relapses as ON as they grow older.[11] Optic neuritis in MOGAD may present with unilateral or bilateral vision loss, visual field defects, color vision impairment, and/or painful eye movements.[1] However, the disease course of MOGAD-ON in children is generally milder than in adults, with higher rates of complete recovery.[12]

The International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group (IPMSSG) defines ADEM using the following diagnostic criteria, all of which must be met:[13]

- A first polyfocal, clinical CNS event with presumed inflammatory demyelinating cause

- Encephalopathy that cannot be explained by fever

- No new clinical and MRI findings emerge three months or more after the onset

- Brain MRI is abnormal during the acute (threemonth) phase.

- Typically on brain MRI:

- Diffuse, poorly demarcated, large (>1–2 cm) lesions involving predominantly the cerebral white matter

- T1 hypointense lesions in the white matter are rare

- Deep grey matter lesions (e.g. thalamus or basal ganglia) can be present

Encephalopathy is therefore required for diagnosis. However, in children signs may be subtle or fluctuating, manifesting as behavioral changes or altered consciousness, which can make recognition challenging.[13]

Among pediatric patients who present with MOGAD-ON (most often >11 years), bilateral involvement is common, either clinically or radiologically. [13] Optic disc edema is frequently observed in pediatric MOGAD-ON, but since it also occurs in a higher proportion of pediatric AQP4-ON and double-seronegative ON compared with adults, its diagnostic value in distinguishing conditions is limited in children.[1]

Approximately 4% of pediatric MOGAD patients present with neuromyelitis optica (NMO).[14][1] NMO is characterized by recurrent uni- or bilateral ON and/or longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis or brainstem syndromes such as area postrema syndrome.[14] In a European prospective cohort, 58% of pediatric NMOSD (neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder) cases were MOG antibody-positive and 17% were AQP4 antibody-positive, whereas in adults, up to 80% of NMOSD cases are associated with AQP4 antibodies.[15] Other less common presentations of pediatric MOGAD include cortical encephalitis, leukodystrophy-like phenotypes, and overlap syndromes.[16][1]

The differential diagnosis of pediatric ADEM is broad and includes multiple sclerosis, AQP4-NMOSD, viral encephalitis, CNS vasculitis, mitochondrial disorders, malignancies, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.[17]

Imaging

MRI findings in MOGAD vary according to the presenting phenotype (e.g., ADEM vs. ON), although some overlap exists.

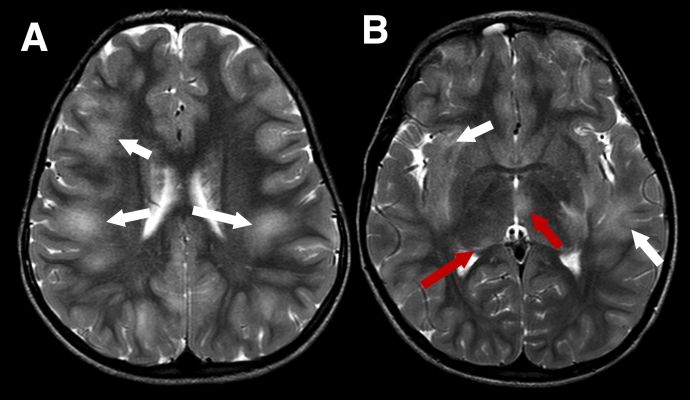

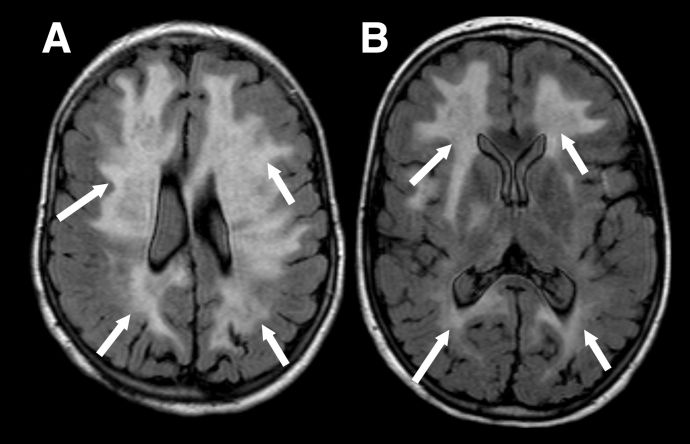

Because MOGAD in younger children more often presents as ADEM, the MRI appearance in this age group differs from that typically observed in adults. In ADEM, MRI commonly shows bilateral, poorly demarcated, T2-hyperintense lesions involving both deep white and gray matter. These lesions are usually large (>2 cm) (Figure 1). In pediatric ADEM associated with MOGAD, MRI findings can present a “leukodystrophy-like” pattern, characterized by confluent, bilateral white matter changes, which is associated with a less favorable prognosis (Figure 2).[18]

Figure 1 Typical imaging appearances in a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) MOGAD phenotype in the acute phase. Axial T2-weighted images show large, extensive, ill defined areas of high signal throughout the subcortical white matter and left temporal stem (A and B, white arrows). The thalami are also involved more inferiorly (B, red arrows)

Figure 2 "Leukodystrophy-like" pattern of demyelination. Axial FLAIR images in a child with the leukodystrophy-like MOGAD phenotype showing extensive, bilateral, relatively symmetrical, areas of markedly increased signal throughout the supratentorial white matter (A and B, white arrows).

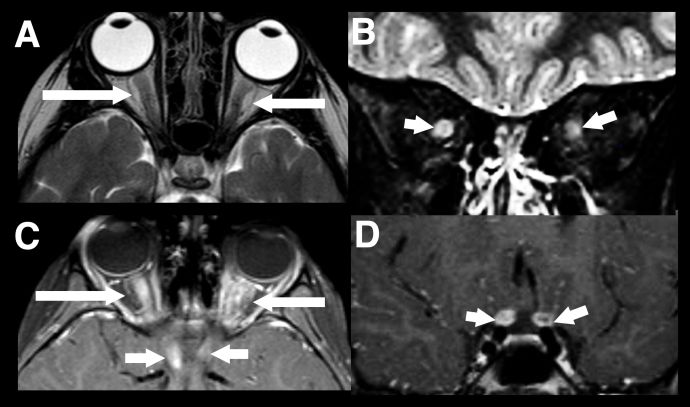

The second most common presentation of pediatric MOGAD is optic neuritis (ON). In children, MRI findings typically reveal bilateral, longitudinally extensive involvement of the optic nerve (affecting more than half of the prechiasmatic segment) with a predilection for the anterior optic nerve, which explains the higher frequency of optic disc swelling (Figure 3).[19] [20]

Figure 3 Longitudinally extensive optic neuritis. Typical imaging findings in a child with acute bilateral MOGAD optic neuritis. There is extensive marked swelling of the intraorbital optic nerve-sheath complexes bilaterally on T2-weighted images, particularly on the right (axial A, and coronal B, white arrows). Marked associated enhancement extending to the prechiasmatic segments of both nerves, are seen on post gadolinium T1-weighted images (axial C and coronal D, white arrows).

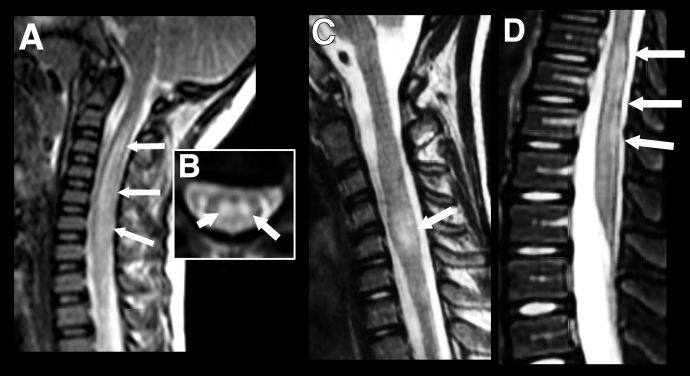

Pediatric patients can present with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) which can occur as part of a wider spectrum of disease or rarely as an isolated presentation. It is defined as a T2-hyperintensity which occurs over three or more vertebral segments (Figure 4). In children, it is most often associated with an ADEM phenotype or NMOSD and normally involves the cervical region of the spine.[21] While short (<3 vertebral segments) transverse myelitis has been reported within the context of pediatric MOGAD, it is a rarer disease phenotype than that seen in adults (Figure 4). [22] In general, gadolinium enhancement of lesions in pediatric MOGAD patients is less prominent than in adults and, where present, is often diffuse and not confined to discrete, patchy lesions as seen in adults.[23]

Figure 4 Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) vs Short transverse myelitis. Imaging findings in transverse myelitis in pediatric MOGAD in the acute phase. A: Sagittal T2-weighted image showing longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, with increased signal and marked swelling of the cervical cord. Corresponding mid-cervical axial image (B) shows typical central cord involvement. Comparison case from another child shows a short segment cervical transverse myelitis, but this also involves the central cord (C, sagittal T2-weighted image) as well as a more typical longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis in the lumbar cord (D).

Management

General Treatment

The treatment of pediatric MOGAD in the acute setting is broadly similar to adults, though special considerations apply in children. It is worth noting that many of the treatment trials in MOGAD and demyelinating disease have been conducted in adults and the results have been extrapolated to children, with no currently published RCT involving exclusively pediatric patients.

Cohort studies regarding children with MOGAD, report that acute treatment strategies typically involve intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP), sometimes followed by an oral prednisone taper, as well as intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) and plasma exchange (PLEX). [24]

Intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP): In large retrospective and cohort studies, IV methylprednisolone (IVMP) is used in nearly all acute pediatric cases,[25] typically at 20-30 mg/kg/day (max ~1 g/day) for 3-5 days. If needed, this is followed by a prednisone/steroid taper over several weeks to months per tolerability. The EU paediatric MOG consortium suggests a tapering period not extending beyond a total of three months.[24] Early escalation to intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) or plasma exchange (PLEX) is recommended in children who do not respond rapidly to IVMP.

Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG): Overall, IVIG has a favorable side effect profile and is generally well tolerated in pediatric . The use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) during the acute phase of MOG antibody-associated disease (MOGAD), either following or alongside intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP), has been reported and is associated with favorable recovery outcomes.[24] [26]Typically, IVIG is administered over 1–5 days at a total dose of 1–2 g/kg (not exceeding 1 g/kg/day). Retrospective data suggest that acute IVIG treatment can lead to significant improvements in visual acuity and disability (EDSS) at ≥3 months.[27]

Plasma exchange (PLEX): The goal of plasma exchange (PLEX) is to remove circulating pathogenic molecules to halt disease activity. PLEX has been used as escalation therapy during the acute phase for both adult and pediatric MOGAD patients, typically administered either following or alongside IVMP. Retrospective studies indicate that the timing of PLEX is critical: a short delay to PLEX was the strongest predictor of complete recovery in patients with NMOSD,[28] and other studies have similarly shown that delayed PLEX is associated with worse clinical outcomes.[29][30]

In a retrospective review of 75 children with MOGAD, early initiation of immunotherapy (within seven days of symptom onset) was associated with a 6.7-fold reduction in relapse risk. The same study also found that a longer steroid taper of five weeks or more significantly reduced the risk of relapse.[31]

Maintenance treatment: Steroid-sparing maintenance immunosuppression with agents like azathioprine or myocophenolate mofetil (MMF) is commonly used, though tolerability, risk of infection, and other adverse effects must be carefully monitored. It is worth noting that pediatric patients are particularly at risk of relapse during the first 3-6 months of initiation of steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents and therefore the EU pediatric MOG consortium suggests co-treatment with an oral steroid taper during establishment of long-term immunosuppression.[24]

The long-term risks of both steroid and steroid-sparing agents in pediatric patients is largely the same as those in adults. There are additional considerations on growth with corticosteroids use in children and there is potentially an increased life-time malignancy risk when agents such as azathioprine and MMF are initiated at a young age, although there is no cohort data to support this currently.[32]

Additional pediatric considerations include impacts on growth and development, schooling, psychological health, visual rehabilitation, family burden. Because of these, management should be via multidisciplinary teams (pediatric neurology, ophthalmology, rehabilitation, psychology, etc.), with close longitudinal follow-up.

Prognosis

Pediatric patients have good recovery, with studies suggesting less long-term disability compared with adults.[33] In pediatric patients, between 75% and 96% were reported to have a complete recovery. Of those patients who present with MOG-ON, there is complete recovery of visual acuity in 56%–73% of patients, which is better than that of adult patients.[20] Pediatric MOG-ON have also been shown to have better recovery compared with adults even when they share similar OCT findings with respect to neuroaxonal loss.[34] Furthermore, within the pediatric patient cohort age, a later age of onset is linearly correlated with a worse visual outcome.[34] Particularly in young patients with MOGAD, there is a predominance of monophasic disease and a good response to initial treatment.[35] Long-term risk of relapse is around 35%, but relapse rates in children are lower than that in adults (Hazard ratio 1.42).[3][36] Early relapses with 12 months of initial onset increase the risk of long-term relapsing disease.[37]

As with adults, a recurrence or multiphasic disease course is associated with a poorer outcome and full recovery is around half that of patients with a monophasic disease course (31-50%).[9] 50% of pediatric patients with multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis (MDEM) were found to have cognitive problems in a prospective 2-year study reporting the outcomes of children with relapsing MOGAD.[11] In the same study, no patients with recurrent ON alone (i.e., no episodes of ADEM or NMOSD) developed cognitive problems. However, the risk of visual loss is high in patients with recurrent MOGAD-ON. A diagnosis of MOGAD at the first episode of ON is important to guide management in patients with relapsing disease.

Conclusion

Pediatric MOGAD demonstrates several unique features compared with adult-forms of the diseases. Treatment guidelines have largely been extrapolated from evidence obtained from adult studies, and treatment RCTs are required to clarify whether current pediatric MOGAD treatment practices are optimal.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Bruijstens AL, Lechner C, Flet-Berliac L, Deiva K, Neuteboom RF, Hemingway C, et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 1 - Classification of clinical phenotypes of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol [Internet]. 2020 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];29:2–13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33162302/

- ↑ de Mol CL, Wong YYM, van Pelt ED, Wokke BHA, Siepman TAM, Neuteboom RF, et al. The clinical spectrum and incidence of anti-MOG-associated acquired demyelinating syndromes in children and adults. Multiple Sclerosis Journal [Internet]. 2020 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];26(7):806–14. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1352458519845112

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cobo-Calvo A, Ruiz A, Rollot F, Arrambide G, Deschamps R, Maillart E, et al. Clinical Features and Risk of Relapse in Children and Adults with Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. Ann Neurol [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];89(1):30–41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32959427/

- ↑ Ramanathan S, Prelog K, Barnes EH, Tantsis EM, Reddel SW, Henderson APD, et al. Radiological differentiation of optic neuritis with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies, aquaporin-4 antibodies, and multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2016 Apr 1;22(4):470–82.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sechi E, Cacciaguerra L, Chen JJ, Mariotto S, Fadda G, Dinoto A, et al. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD): A Review of Clinical and MRI Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Front Neurol [Internet]. 2022 Jun 17 [cited 2023 Oct 31];13:885218. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9247462/

- ↑ Waters P, Fadda G, Woodhall M, O’Mahony J, Brown RA, Castro DA, et al. Serial Anti–Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody Analyses and Outcomes in Children With Demyelinating Syndromes. JAMA Neurol [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Nov 11];77(1):82–93. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6763982/

- ↑ Sechi E, Cacciaguerra L, Chen JJ, Mariotto S, Fadda G, Dinoto A, et al. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD): A Review of Clinical and MRI Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Front Neurol [Internet]. 2022 Jun 17 [cited 2023 Oct 31];13:885218. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9247462/

- ↑ Ketelslegers IA, Van Pelt ED, Bryde S, Neuteboom RF, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Hamann D, et al. Anti-MOG antibodies plead against MS diagnosis in an Acquired Demyelinating Syndromes cohort. Mult Scler [Internet]. 2015 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];21(12):1513–20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25662345/

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Zhou J, Lu X, Zhang Y, Ji T, Jin Y, Xu M, et al. Follow-up study on Chinese children with relapsing MOG-IgG-associated central nervous system demyelination. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019 Feb 1;28:4–10.

- ↑ Santoro JD, Beukelman T, Hemingway C, Hokkanen SRK, Tennigkeit F, Chitnis T. Attack phenotypes and disease course in pediatric MOGAD. Ann Clin Transl Neurol [Internet]. 2023 May 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];10(5):672. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC10187731/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hacohen Y, Absoud M, Deiva K, Hemingway C, Nytrova P, Woodhall M, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies are associated with a non-MS course in children. Neurology(R) neuroimmunology & neuroinflammation [Internet]. 2015 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];2(2):e81. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25798445/

- ↑ Ketelslegers IA, Visser I, Neuteboom RF, Boon M, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Hintzen RQ. Disease course and outcome of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is more severe in adults than in children. Mult Scler [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2023 Nov 23];17(4):441–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21148017/

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Krupp LB, Tardieu M, Amato MP, Banwell B, Chitnis T, Dale RC, et al. International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group criteria for pediatric multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated central nervous system demyelinating disorders: revisions to the 2007 definitions. http://dx.doi.org/101177/1352458513484547 [Internet]. 2013 Apr 9 [cited 2023 Oct 31];19(10):1261–7. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1352458513484547

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, Cabre P, Carroll W, Chitnis T, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology [Internet]. 2015 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Nov 11];85(2):177–89. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26092914/

- ↑ Lechner C, Baumann M, Hennes EM, Schanda K, Marquard K, Karenfort M, et al. Antibodies to MOG and AQP4 in children with neuromyelitis optica and limited forms of the disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry [Internet]. 2016 Jan 8 [cited 2023 Nov 11];87(8):897–905. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26645082/

- ↑ Kannan V, Sandweiss AJ, Erickson TA, Yarimi JM, Ankar A, Hardwick VA, et al. Fulminant Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein-Associated Cerebral Cortical Encephalitis: Case Series of a Severe Pediatric Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease Phenotype. Pediatr Neurol [Internet]. 2023 Oct 1 [cited 2023 Nov 23];147:36–43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37544084/

- ↑ Baumann M, Bartels F, Finke C, Adamsbaum C, Hacohen Y, Rostásy K, et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 2 – Neuroimaging features of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2020 Nov 1;29:14–21.

- ↑ Hacohen Y, Rossor T, Mankad K, Chong W ‘Kling,’ Lux A, Wassmer E, et al. ‘Leukodystrophy-like’ phenotype in children with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Dev Med Child Neurol [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Nov 23];60(4):417–23. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dmcn.13649

- ↑ Wendel EM, Baumann M, Barisic N, Blaschek A, Coelho de Oliveira Koch E, Della Marina A, et al. High association of MOG-IgG antibodies in children with bilateral optic neuritis. Eur J Paediatr Neurol [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];27:86–93. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32327391/

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Song H, Zhou H, Yang M, Tan S, Wang J, Xu Q, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-seropositive paediatric optic neuritis in China. Br J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];103(6):831–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30049802/

- ↑ Baumann M, Grams A, Djurdjevic T, Wendel EM, Lechner C, Behring B, et al. MRI of the first event in pediatric acquired demyelinating syndromes with antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. J Neurol [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];265(4):845–55. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29423614/

- ↑ Ciron J, Cobo-Calvo A, Audoin B, Bourre B, Brassat D, Cohen M, et al. Frequency and characteristics of short versus longitudinally extensive myelitis in adults with MOG antibodies: A retrospective multicentric study. Mult Scler [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];26(8):936–44. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31148523/

- ↑ Tantsis EM, Prelog K, Alper G, Benson L, Gorman M, Lim M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in enterovirus-71, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody, aquaporin-4 antibody, and multiple sclerosis-associated myelitis in children. Dev Med Child Neurol [Internet]. 2019 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];61(9):1108–16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30537075/

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Bruijstens AL, Wendel EM, Lechner C, Bartels F, Finke C, Breu M, Flet-Berliac L, de Chalus A, Adamsbaum C, Capobianco M, Laetitia G, Hacohen Y, Hemingway C, Wassmer E, Lim M, Baumann M, Wickström R, Armangue T, Rostasy K, Deiva K, Neuteboom RF. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 5 - Treatment of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2020 Nov;29:41-53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2020.10.005. Epub 2020 Nov 4. PMID: 33176999.

- ↑ Klein da Costa B, Banwell BL, Sato DK. Treatment of MOG-IgG associated disease in paediatric patients: A systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];56. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34450460/

- ↑ Al-Ani A, Chen JJ, Costello F. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD): current understanding and challenges. J Neurol [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Dec 7];270(8):1. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC10165591/

- ↑ Lotan I, Chen JJ, Hacohen Y, Abdel-Mannan O, Mariotto S, Huda S, Gibbons E, Wilf-Yarkoni A, Hellmann MA, Stiebel-Kalish H, Pittock SJ, Flanagan EP, Molazadeh N, Anderson M, Salky R, Romanow G, Schindler P, Duchow AS, Paul F, Levy M. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment for acute attacks in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody disease. Mult Scler. 2023 Aug;29(9):1080-1089. doi: 10.1177/13524585231184738. Epub 2023 Jul 10. PMID: 37431144.

- ↑ Bonnan M, Valentino R, Debeugny S, Merle H, Fergé JL, Mehdaoui H, et al. Short delay to initiate plasma exchange is the strongest predictor of outcome in severe attacks of NMO spectrum disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018 Apr 1 [cited 2023 Dec 7];89(4):346–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29030418/

- ↑ Klein da Costa B, Banwell BL, Sato DK. Treatment of MOG-IgG associated disease in paediatric patients: A systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord [Internet]. 2021 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];56. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34450460/

- ↑ Chen JJ, Flanagan EP, Pittock SJ, Stern NC, Tisavipat N, Bhatti MT, et al. Visual Outcomes Following Plasma Exchange for Optic Neuritis: An International Multicenter Retrospective Analysis of 395 Optic Neuritis Attacks. Am J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2023 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Dec 7];252:213–24. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36822570/

- ↑ Nosadini M, Eyre M, Giacomini T, Valeriani M, Della Corte M, Praticò AD, et al. Early Immunotherapy and Longer Corticosteroid Treatment Are Associated With Lower Risk of Relapsing Disease Course in Pediatric MOGAD. Neurology - Neuroimmunology Neuroinflammation [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Oct 31];10(1). Available from: https://nn.neurology.org/content/10/1/e200065

- ↑ Bruijstens AL, Wendel EM, Lechner C, Bartels F, Finke C, Breu M, et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 5 – Treatment of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2020 Nov 1;29:41–53.

- ↑ Bruijstens AL, Breu M, Wendel EM, Wassmer E, Lim M, Neuteboom RF, et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 4 e Outcome of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. 2020 [cited 2023 Oct 31]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2020.10.007

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Havla J, Pakeerathan T, Schwake C, Bennett JL, Kleiter I, Felipe-Rucián A, et al. Age-dependent favorable visual recovery despite significant retinal atrophy in pediatric MOGAD: how much retina do you really need to see well? J Neuroinflammation [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Nov 23];18(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34051804/

- ↑ Bruijstens AL, Wendel EM, Lechner C, Bartels F, Finke C, Breu M, et al. E.U. paediatric MOG consortium consensus: Part 5 – Treatment of paediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2020 Nov 1;29:41–53.

- ↑ Satukijchai C, Mariano R, Messina S, Sa M, Woodhall MR, Robertson NP, et al. Factors Associated With Relapse and Treatment of Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody–Associated Disease in the United Kingdom. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2022 Jan 4 [cited 2023 Nov 23];5(1):e2142780–e2142780. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2787769

- ↑ Chen B, Gomez-Figueroa E, Redenbaugh V, Francis A, Satukijchai C, Wu Y, et al. Do Early Relapses Predict the Risk of Long-Term Relapsing Disease in an Adult and Paediatric Cohort with MOGAD? Ann Neurol [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Nov 23];94(3):508–17. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37394961/