Reverse Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect (RAPD)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Overview

A relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD), also known as a Marcus Gunn pupil, is a critically important ophthalmological examination finding that defines a pathological defect in the pupil pathway on the afferent side. In normal individuals, there is bilateral and equal innervation of the pupils. An RAPD manifests as a difference in pupillary light reaction between the two eyes and is diagnosed relative to the fellow eye, though it only requires one working pupil. Patients with RAPD do not have anisocoria.

An RAPD involves unilateral or bilateral but asymmetric lesions of the prechiasmal optic nerve starting from the retina, but it can occur anywhere in the afferent pupillary pathway.[1][2] Conditions leading to RAPD occur in front of the lateral geniculate body in either the anterior optic pathway or in the retina/posterior segment:

Lesions of the Anterior Optic Pathway

- Optic nerve, regardless of the cause of optic neuropathy (e.g., optic neuritis, glaucoma, compression, infection)

- Optic chiasm

- Optic tract

- Pretectum

Lesions of the Retina/Posterior Segment

- Large retinal detachments

- Ischemia (e.g., ischemic central retinal vein occlusion, central retinal artery occlusion)

- Dense macular lesions (chorioretinal scar)[2]

Procedures

Swinging Flashlight Test

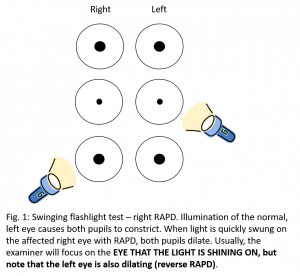

When assessing for an afferent pupillary pathway lesion, the light response is tested individually in each eye, and then the light is swung between the two eyes. The normal pupillary response is characterized by equal constriction of the pupils in both eyes when the light stimulus is applied to each eye individually and no dilation or pupillary escape when the light swings from one eye to the other. The pathologic response that characterizes RAPD includes pupillary constriction in both eyes when the light shines in the normal eye, and dilatation of the pupils in both eyes when the light stimulus is rapidly transferred from the normal eye to the pathologic eye.[2] The RAPD is a critically important sign in patients with unexplained visual loss because it is an objective finding of afferent pupillary dysfunction.[1]

Reverse Testing for RAPD

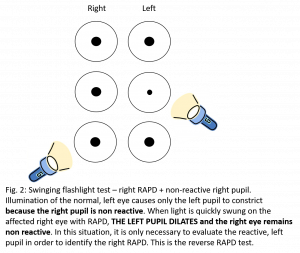

Testing for a RAPD requires two eyes but only one functioning pupil. When one eye has an efferent pupillary defect (e.g., iris posterior synechiae, trauma, third nerve palsy, pharmacological mydriasis), a "reverse RAPD" test can be employed.[2][3] Reverse RAPD, or reverse testing for RAPD, utilizes the swinging flashlight test while evaluating the normal, unaffected pupil for dilation. Most examiners are used to only observing the affected pupil during the swinging flashlight test, but both pupils dilate in every RAPD. In the setting of a patient with both an afferent and efferent pupillary defect, the reverse test is used, in which the clinician will observe the unaffected pupil for dilation (rather than the affected pupil).

Figure 1 shows the results of the swinging flashlight test in a right pupil with both an afferent pupillary defect and a fixed pupil from an efferent pupillary defect. When the light is shone onto the normal left pupil—or swings from the abnormal right pupil to the normal left pupil—the left pupil constricts but the fixed right pupil does not. When the light swings from the normal left pupil back to the abnormal right pupil, the left pupil dilates.[2][3][4] This reverse testing result is indicative of a right RAPD.

Figure 2 shows the results of the swinging flashlight test in a patient with a right RAPD and a nonreactive right pupil. In this instance, the left pupil should be watched for the duration of the examination to identify if there is an RAPD.

Indications

A reverse RAPD should be evaluated in every patient with an efferent pupillary defect. For example, in a patient with a cranial nerve (CN) III palsy with a dilated pupil, one of the main diagnostic considerations is possible aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery. In this setting, a CN III palsy is potentially life-threatening and urgent vascular imaging may be necessary (e.g., computed tomography (CT) and CT angiogram of the brain). However, if this same patient also has an RAPD, then the localization of the lesion moves from the posterior communicating artery to the orbital apex. Some clinicians may neglect to check for an RAPD by reverse testing because they are misled into believing that the fixed and dilated pupil precludes assessment of that pupil’s afferent response.[5]

Clinicians should be aware that it is possible to test for an RAPD in any patient with two eyes and at least one working pupil. The reverse RAPD is present every time because both pupils dilate when the light swings from the normal pupil to the abnormal pupil, but in a reverse RAPD the clinician is observing the normal pupil when the light swings from the normal eye to the affected eye.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Vejdani MD., Al-Zubidi N. Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect. Eyewiki 2020. https://eyewiki.org/Relative_Afferent_Pupillary_Defect

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Simakurthy S., Tripathy K. Marcus Gunn Pupil. StatPearls [Internet], 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Broadway DC. How to test for a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Community Eye Health, 2012;25(79-80):58-59.

- ↑ Raabe J., Lyons LJ., Al Othman [TC1] B., Lee AG. True and False Localization in Neuro-ophthalmology—A Report of Two Cases. US Ophthalmic Review, 2019;12(2):98-102.

- ↑ Lee AG., Gonzalez Y (Ed.). [TC1] Reverse Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect (RAPD) LOLLC. Neuro-ophthalmology Virtual Education Library: NOVEL, 2020. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6fz2vsm.