Review of Topical Glaucoma Medications

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Topical ocular antihypertensives lower intraocular pressure (IOP) via a few main mechanisms. Prostaglandins are often considered first-line medical therapy for glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Currently-used topical therapies are generally well-tolerated, but commonly cause ocular surface issues. Prostaglandins have unique side effects; beta blockers and alpha agonists have important systemic side effects that may be life-threatening.

Introduction

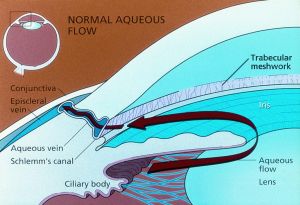

Glaucoma is a progressive optic neuropathy for which the only known modifiable risk factor is intraocular pressure (IOP).[1][2] Current medical therapies are aimed towards reduction of IOP, which is influenced by (according to the Goldmann equation) aqueous production from the nonpigmented epithelium of the ciliary body, outflow facility through the trabecular meshwork (the "conventional" pathway), uveoscleral outflow (the "unconventional" pathway), and episcleral venous pressure.[3]

Overview

Glaucoma medications decrease aqueous production or increase outflow facility via the conventional or uveoscleral routes.[3]

The following medication classes (notably the A B C's) decrease aqueous production:

- alpha agonists

- beta blockers

- carbonic anhydrase inhibitors

The following medication classes increase trabecular or uveoscleral outflow:

- rho kinase inhibitors

- alpha agonists (brimonidine)

- miotics

- prostaglandin analogues

Summary table

See below for a table summarizing primary mechanisms of action and adverse effects.[3] Further details may be found in each medications' subsection.

Abbreviations: TM, trabecular meshwork; SC, Schlemm's canal; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MAO, monoamine oxidase; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant

| Medication class | Year approved (USA)[4] | Dosing | IOP-lowering effect (from untreated baseline) | Estimated cost (USD/mL)[5] | Primary mechanism(s) of action | Prominent examples | Select adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostaglandins | 1996 | Once daily | ~30% | $6.19 | ↑ uveoscleral outflow (possibly via MMP-mediated remodeling) | latanoprost, travoprost, bimatoprost, tafluprost, latanoprostene bunod |

|

| Beta blockers | 1978 | 1-2x daily | 20-30% | $1.66 | ↓ aqueous secretion (via inhibiting cAMP production in ciliary epithelium) | betaxolol (β1-selective), carteolol, levobunolol, metipranolol, timolol |

|

| Alpha agonists | 1987 | 2-3x daily | 14-26% | $1.90 | ↓ aqueous secretion (via inhibiting cAMP production in ciliary epithelium; possibly anterior segment vasoconstriction) | brimonidine, apraclonidine |

|

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors | 1954 | 2-3x daily | 15-20% | $1.76 | ↓ aqueous secretion (via inhibiting carbonic anhydrase in ciliary epithelium) | dorzolamide, brinzolamide |

|

| Rho-kinase inhibitors | 2017 | Once daily | 20% | $130.95 | ↑ conventional outflow (via cytoskeletal relaxation in the TM and SC) | netarsudil |

|

| Miotics (direct-acting) | 1877 | 3-4x daily | 15-25% | $2.19 | ↑ conventional outflow (via contraction of longitudinal ciliary muscle fibers) | pilocarpine |

|

Prostaglandin analogues (PGAs)

Since the introduction of latanoprost more than 30 years ago, prostaglandin analogs (PGAs) have become a widely used first-line treatment for glaucoma. The four commonly prescribed agents, latanoprost, travoprost, bimatoprost, and tafluprost, have all demonstrated effective IOP reduction with minimal adverse effects. They lower IOP primarily by enhancing uveoscleral outflow, with minor contributions to trabecular outflow and aqueous humor production[6]. This is thought to occur through altered regulation of matrix metalloproteinases, leading to extracellular matrix remodeling and increased permeability of outflow pathways. [7]

PGAs have been shown to reduce IOP by 25–32% and maintain this effect over a full 24-hour period, enabling once-daily dosing. [6] A trial involving 829 patients with elevated IOP found that six months of latanoprost therapy reduced IOP by 35% when administered in the evening and by 31% when administered in the morning, leading many clinicians to recommend bedtime dosing.[8][9] Initial clinical trials of latanoprost demonstrated that IOP reduction begins within 3–4 hours, peaks at 8–12 hours, and persists for at least 24 hours. [10] However, the overall maximal effect may not be reached until 3–5 weeks after therapy initiation. [6]

Latanoprost has shown greater IOP-lowering efficacy compared with timolol, brimonidine, or dorzolamide. [7] Multiple trials comparing PGAs to one another have demonstrated similar effectiveness. Notably, bimatoprost has been compared with latanoprost in several studies, with mixed results: some found no significant difference between the two agents[11] [12][13], while others reported that bimatoprost produced greater, though not always significantly greater, IOP reductions.[14] [15][16] Travoprost and tafluprost have also been shown to provide IOP-lowering effects equivalent to latanoprost.[7]

Although generally well tolerated, PGAs can cause permanent darkening of the iris and periocular skin due to an increased number of melanosomes within melanocytes.[9] Other commonly reported adverse effects include conjunctival hyperemia and hypertrichosis, both of which occur less frequently with latanoprost compared to other PGAs.[7] Ocular surface irritation is also common but can be reduced by using preservative-free formulations.[7] Less frequently, PGAs may induce or worsen preexisting cystoid macular edema (CME) or cause deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus.[6][11]

Overall, PGAs are highly effective and well tolerated for lowering IOP, making them an excellent first-line choice for patients with glaucoma.

Latanoprostene bunod

Latanoprostene bunod (LBN) was FDA-approved in 2017 and is a PGA that additionally contains a nitric oxide (NO)-donating moeity with a side effect profile similar to PGAs.[17][18] After LBN is metabolized, NO induces relaxing trabecular meshwork and Schlemm's canal, increasing conventional outflow.[19]

β-Adrenergic Antagonists (beta blockers)

Topical beta-blockers have been a mainstay of glaucoma treatment since the late 1970s. [20] These agents reduce IOP by inhibiting sympathetic nerve endings in the ciliary epithelium, thereby decreasing aqueous humor production.[8][21] Of the five commercially available topical beta-blockers, timolol, levobunolol, metipranolol, and carteolol are nonselective agents, with timolol being the most widely used.[21] Betaxolol, in contrast, is cardioselective and is preferred when nonselective beta-blockers are contraindicated, though it may be less effective at lowering IOP. [8][21] Timolol is available in two formulations, 0.25% and 0.5%, and clinical experience suggests that both produce similar IOP-lowering effects in many patients. [8] Most beta-blockers are approved for twice-daily dosing, although once-daily use, typically in the morning, can be effective in many cases. [8]

Beta-blockers are generally well tolerated but may cause blurred vision, ocular irritation, or allergic reactions in some patients. Potential systemic adverse effects include bronchospasm, bradycardia, heart block, hypotension, and, rarely, central nervous system depression.[8] Nonselective beta-blockers should be used cautiously in patients with asthma, with betaxolol or other drug classes preferred in such cases.[8][22][23] Similarly, beta-blockers should be avoided in patients with significant bradycardia or heart block. Overall, these medications remain a common and effective choice for managing glaucoma due to their safety and efficacy.

Adrenergic Agonists

Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists are another class of autonomic agents useful for the management of glaucoma. The two main drugs include apraclonidine and brimonidine, with the latter more widely used due to improved tolerability and a more favorable side-effect profile. [24]

Apraclonidine primarily lowers IOP via inhibiting aqueous humor production. However, its effects are much weaker than brimonidine and is rarely used for long-term therapy.[25] Instead, it is utilized perioperatively to minimize IOP spikes.[3][26]

Brimonidine is a highly selective alpha-2 agonist that reduces IOP through inhibiting aqueous humor production and increasing uveoscleral outflow with reductions similar to that of timolol.[3][27] While approved for up to three times a day, it is often dosed twice daily and studies have shown inconclusive additional benefit with a third dose.[28] Brimonidine is often used as part of a multidrug regimen with synergistic effects demonstrated when used with other classes such as CAIs, beta-blockers, and PGAs.[29]

Common adverse effects of alpha-2 agonists include conjunctival hyperemia, allergic conjunctivitis, and ocular pruritus.[3][29] They are also associated with tachyphylaxis and blepharoconjunctivitis, though more so with apraclonidine.[3] Systemic effects are less common though can include dry mouth and CNS depression with hypotension, fatigue, and bradycardia.[28][29] Due to the CNS effects, these drugs should be avoided in infants and young children.[3]

Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors (CAIs)

Since their discovery in the 1950s, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) have been utilized as systemic medications for non-glaucoma indications. However, in 1955, it was determined that this class of medication reduces aqueous humor production via inhibiting ciliary epithelial carbonic anhydrase and can be used to manage glaucoma. [3][30] The first generation CAIs are systemic medications and include acetazolamide, methazolamide, dichlorophenamide, and ethoxzolamide. Among these, acetazolamide is the most widely used for pressure reduction. These CAIs begin to act within an hour of ingestion, with maximal effect within 2–4 hours.[3] This allows them to be utilized for emergent, short-term situations, but rarely for long-term management due to systemic side effects. Common adverse effects include metabolic acidosis, paresthesias of extremities, metallic taste, depression, fatigue, and renal calculi. [3][30]

While first generation CAIs have IOP-lowering effects, their use topically is limited by poor corneal penetration. Therefore, a second generation of CAIs was developed to be both water and lipid soluble making them more effective via topic route.[31] [32]These include dorzolamide and brinzolamide which have been shown to lower IOP by 15-20% with fewer systemic side effects than oral CAIs. While not first line, topical CAIs are often used as alternative or adjunctive medications for managing glaucoma.[33] These drops are approved for up to thrice daily dosing, though are often prescription for twice daily.[3][31] Common side effects include stinging, burning, blurred vision, pruritus, and bitter taste. Since CAIs are derived from sulfa drugs they can cause an allergic reaction in individuals with sulfa allergies though the level of cross- reactivity is low. [3]

Parasympathomimetic Agents (Miotics)

Although less commonly used than other therapeutic classes, parasympathomimetic agents have been employed in the management of glaucoma for over a century.[3] These agents enhance parasympathetic activity in the eye, inducing ciliary muscle contraction and pupillary constriction. Contraction of the ciliary muscle facilitates opening of the trabecular meshwork via the scleral spur, thereby increasing aqueous humor outflow and reducing IOP, while pupillary constriction can contribute to angle opening in eyes with narrow or occludable angles.[3][34] This unique mechanism makes mitotic agents useful in management of specific conditions such as pigmentary glaucoma, aphakic glaucoma, and plateau iris syndrome.[3][35]

Direct-acting cholinergic agonists, most notably pilocarpine, stimulate muscarinic acetylcholine receptors directly, whereas indirect-acting cholinergic agents inhibit acetylcholinesterase, thereby prolonging the action of endogenous acetylcholine.[3] Indirect agents, namely echothiophate iodide, have largely fallen out of favor due to adverse effects, such as iris pigment epithelial cysts, though they can be helpful in aphakic glaucoma.[3]

Due to their mechanism of action, parasympathomimetic agents can induce myopia, which may impair vision, particularly in low-light conditions. This effect, however, can improve near vision in presbyopic patients. Other ocular side effects include brow ache, retinal detachment, and cataract formation. Because these drugs can disrupt the blood–aqueous barrier, they should be avoided in patients with uveitic glaucoma.[3]

Besides chronic IOP control, pilocarpine is frequently used prior to laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI), as its effects of iris flattening and thinning can improve procedural safety and efficacy.[36] It has also been used to pretreat eyes before argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT) with the aim of mitigating postoperative IOP spikes. However, its efficacy in this role is uncertain; a comparison of three studies found no clear advantage to using pilocarpine for prophylaxis of ALT.[26]

Rho-Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitors

Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitors are a newer class of medication for glaucoma thought to reduce IOP by increasing conventional outflow through the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal along with decreasing aqueous humor production and reducing episcleral pressure.[3][37] Ripasudil was the first ROCK inhibitor approved for clinical use in Japan in 2014. Clinical trials demonstrated its IOP lower effect within 2 hours of administration and additive effects when combined with other medication such as latanoprost. In 2017, netarsudil (Rhopressa®), was approved for clinical use in the United States at a dose of once per day. In trials, netarsudil achieved IOP reductions comparable to timolol, though less than those observed with latanoprost.[38][39] A combined formula of latanoprost and netarsudil proved more effective at lower IOP than either of the components individually leading to the approval of netarsudil/latanoprost FDC (Rocklatan®) in 2019.[40]

The most common adverse effects of ROCK inhibitors are conjunctival hyperemia which is generally mild and short-lived. Other potential side effects include cornea verticillata (similar to those seen with amiodarone use), conjunctival hemorrhage, blepharitis, reticular corneal edema and allergic conjunctivitis.[37]

Beyond IOP lowering, ROCK inhibitors have demonstrated neuroprotective and axon-regenerative effects in animal models, potentially mediated by increased optic nerve head blood flow.[37] ROCK inhibition may inhibit scarring after glaucoma filtration surgeries via inhibiting TGF-β and therefore fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast transdifferentiation.[37][41] These medications are also being studied in corneal endothelial disease.[42]

Combined medications

Many patients will need multiple medications to manage their glaucoma.[43][44] Combination drops are excellent alternatives for multi-drug management to increase compliance and reduce drop burden for patients.[45] Besides specialized compound drops, many fixed-combination drops have been developed and are widely used for patients with glaucoma. A majority of the commercially available, fixed combination drops in the United States include timolol with another class. Major exceptions to this include brinzolamide/brimonidine (SIMBRINZA®) and netarsudil/latanoprost (Rocklatan®) among others.

One of the oldest and most widely used fixed-combination drops is dorzolamide/timolol (Cosopt®). Dosed at twice a day, this drop provides better IOP control than the same agents given separately, likely due to elimination of the washout effect from sequential instillation.[44][46] Common adverse effects include burning/stinging, blurred vision, and conjunctival hyperemia.[47]

Brimonidine/timolol (Combigan®) is a commonly used fixed-combination drop with similar results to dorzolamide-timolol.[48] The drop provides greater IOP reduction than either component alone and demonstrates noninferiority compared with concomitant use of the two agents separately.[48] Common adverse effects include conjunctival hyperemia, stinging, allergic conjunctivitis, conjunctival folliculosis though multiple studies concluded the combination was better tolerated than brimonidine monotherapy.[48]

Brinzolamide/brimonidine (SIMBRINZA®) was the first fixed-combination drop approved in the United States that does not include timolol. Twice daily dosing has been shown to provide superior IOP reduction compared with either agent alone and is noninferior to concomitant separate therapy.[49] Common adverse effects include blurred vision, ocular irritation/ hyperemia, and dry eye.

Netarsudil/latanoprost (Rocklatan®) is a newer fixed-combination drop that has demonstrated superior IOP-lowering efficacy compared with monotherapy with either netarsudil or latanoprost alone.[40][50] Once-daily dosing makes this combination desirable for increasing compliance though cost is often a prohibiting factor. The most common adverse effect is conjunctival hyperemia, which occurs more frequently with the combination than with either component alone.[50] Other reported ocular side effects are generally mild and self-limited including corneal verticillata and conjunctival hemorrhage.[40]

Considerations

Selection of therapy should be based on severity and progression of disease and individual patient characteristics.

Medication selection

Current first-line therapies for primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension include prostaglandin analogues[51] [52](due to their superior efficacy, once daily dosing, and safety profile) and increasingly laser trabeculoplasty (which can also be used during escalation of care). Topical beta blockers may also be considered, though they have notable systemic side effects.

Medications are typically added sequentially unless IOP is acutely or dangerously elevated, during which multiple classes may be initiated at once. After prostaglandins, other agents have similar mean IOP-lowering effects, but carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have better effects on nocturnal IOP.[53][3] The following is an example of therapeutic escalation over time:

- Start latanoprost 0.005% at night

- Add dorzolamide 2% twice daily or timolol 0.5% in the morning (after ensuring the patient has no significant cardiopulmonary comorbidities)

- Switch to dorzolamide/timolol 22.3/6.8 mg twice daily

- Add brimonidine 0.2% twice daily

- Increase brimonidine 0.2% to three times daily

Adherence

Appropriate drop instillation is an important component of adherence, especially in elderly patients who may require assistance in administering their eye drops. Clear and repeated patient-physician discussions are important for maintaining adherence.[3] Patients may find it useful to time their eye drop administration to occur with other habits (eg brushing teeth, going to bed), activities (eg meals), or oral medications. If a patient is scheduled to take different eye drops at the same time, they should wait 5 minutes in between medications to avoid "washing out" the former drop.

If drops' systemic effects limit adherence, patients may close their eyes and perform nasolacrimal occlusion for 1 to 3 minutes after instillation to limit systemic absorption. Gel-based formulations may also decrease systemic absorption.

Source: YouTube. American Academy of Ophthalmology. How To Insert Eyedrops. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KbtymNSJjtw Accessed November 30, 2025.

Ocular surface disease

Most if not all glaucoma may irritate the ocular surface, especially with chronic use. This may in part be due to benzalkonium chloride (BAK). Limiting dosing and/or using combination or preservative-free agents may be useful in patients with ocular surface symptoms.[54]

Other options include using preservative-free artificial tears, compounding pharmacies, oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, or procedures such as laser trabeculoplasty or injectable medications (eg bimatoprost implant).

Pregnant/breastfeeding individuals

There is little definitive information regarding the safety of topical glaucoma medications while pregnant or breastfeeding. Therefore, benefits of continued therapy must be weighed against theoretical teratogenic effects. Strategies to minimize risk include using lower doses, performing nasolacrimal occlusion during drop instillation, or performing incisional or laser surgery to reduce IOP. Below is a table summarizing pregnancy categories for typically-used glaucoma medications.[3] (Notably, the FDA introduced the new Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) in 2015 which replaced the alphabetical categorization system.)

Brimonidine should be avoided in breastfeeding individuals to avoid infant apnea.

| Medication class | Pregnancy Category |

|---|---|

| Prostaglandins | C |

| Beta blockers | C |

| Alpha agonists | B |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors | C |

| Rho-kinase inhibitors | Not assigned |

- Category A: No risk in human studies (no demonstrated risk to human fetus during first trimester)

- Category B: No risk in animal studies (no adequate human studies, no demonstrated risk to animal fetus)

- Category C: Risk cannot be ruled out (no adequate human studies, yes demonstrated risk to animal fetus; benefits may outweigh risks)

- Category D: Evidence of risk (yes demonstrated risk to human fetus; benefits may outweigh risks)

- Category X: Contraindicated (yes demonstrated risk to human fetus, and/or fetal abnormalities; risks outweigh benefits)[55]

Conclusions

Commonly-used topical glaucoma medications are generally safe and efficacious, but have adverse effects that ophthalmologists and primary care physicians should be aware of. Therapy should be tailored based on patients' disease and needs.

References

- ↑ Navid Mahabadi, Zeppieri M, Tripathy K. Open Angle Glaucoma. StatPearls. Published March 7, 2024. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK441887/

- ↑ Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH, Alward WLM. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1113-1124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0804630

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 2025-2026 Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 10: Glaucoma. Chapter 12: Medical Management of Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension.

- ↑ Groves N. Tracing history of glaucoma drugs: Ophthalmology Times - clinical insights for Eye Specialists. Ophthalmology Times. May 10, 2019. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.ophthalmologytimes.com/view/tracing-history-glaucoma-drugs.

- ↑ GOODRX. Prescription Prices, Coupons & Pharmacy Information - GoodRx. www.goodrx.com. Published 2020. https://www.goodrx.com. Accessed October 30, 2025.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Cordeiro MF, Gandolfi S, Gugleta K, Normando EM, Oddone F. How latanoprost changed glaucoma management. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024 Mar;102(2):e140-e155. doi: 10.1111/aos.15725. Epub 2023 Jun 23. PMID: 37350260. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aos.15725

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Alm A. Latanoprost in the treatment of glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014 Sep 26;8:1967-85. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S59162. PMID: 25328381; PMCID: PMC4196887. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25328381/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC) Section 10: Glaucoma. Chapter 10, Medical Management of Glaucoma. 2023–2024 ed. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Alm A, Camras CB, Watson PG. Phase III latanoprost studies in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997 Feb;41 Suppl 2:S105-10. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)80016-1. PMID: 9154285.

- ↑ Camras CB, Alm A. Initial clinical studies with prostaglandins and their analogues. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997 Feb;41 Suppl 2:S61-8. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)80009-4. PMID: 9154278.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Yildirim N, Sahin A, Gultekin S. The effect of latanoprost, bimatoprost, and travoprost on circadian variation of intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2008 Jan-Feb;17(1):36-9. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318133fb70. PMID: 18303382.

- ↑ Orzalesi N, Rossetti L, Bottoli A, Fogagnolo P. Comparison of the effects of latanoprost, travoprost, and bimatoprost on circadian intraocular pressure in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2006 Feb;113(2):239-46. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.045. PMID: 16458092.

- ↑ How AC, Kumar RS, Chen YM, Su DH, Gao H, Oen FT, Ho CL, Seah SK, Aung T. A randomised crossover study comparing bimatoprost and latanoprost in subjects with primary angle closure glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009 Jun;93(6):782-6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.144535. Epub 2009 Mar 30. PMID: 19336424.

- ↑ Gandolfi S, Simmons ST, Sturm R, Chen K, VanDenburgh AM; Bimatoprost Study Group 3. Three-month comparison of bimatoprost and latanoprost in patients with glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Adv Ther. 2001 May-Jun;18(3):110-21. doi: 10.1007/BF02850299. PMID: 11571823.

- ↑ DuBiner H, Cooke D, Dirks M, Stewart WC, VanDenburgh AM, Felix C. Efficacy and safety of bimatoprost in patients with elevated intraocular pressure: a 30-day comparison with latanoprost. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001 May;45 Suppl 4:S353-60. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00212-0. PMID: 11434938.

- ↑ Konstas AG, Katsimbris JM, Lallos N, Boukaras GP, Jenkins JN, Stewart WC. Latanoprost 0.005% versus bimatoprost 0.03% in primary open-angle glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology. 2005 Feb;112(2):262-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.08.022. PMID: 15691561.

- ↑ Kawase K, Vittitow JL, Weinreb RN, Araie M; JUPITER Study Group. Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Latanoprostene Bunod 0.024% in Japanese Subjects with Open-Angle Glaucoma or Ocular Hypertension: The JUPITER Study. Adv Ther. 2016;33(9):1612-1627.

- ↑ Mehran NA, Sinha S, Razeghinejad R. New glaucoma medications: latanoprostene bunod, netarsudil, and fixed combination netarsudil-latanoprost. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(1):72-88.

- ↑ Wiederholt M, Sturm A, Lepple-Wienhues A. Relaxation of trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle by release of nitric oxide. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35(5):2515-2520.

- ↑ Frishman WH, Fuksbrumer MS, Tannenbaum M. Topical ophthalmic beta-adrenergic blockade for the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. J Clin Pharmacol. 1994 Aug;34(8):795-803. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1994.tb02042.x. PMID: 7962666.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Brooks AM, Gillies WE. Ocular beta-blockers in glaucoma management. Clinical pharmacological aspects. Drugs Aging. 1992 May-Jun;2(3):208-21. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199202030-00005. PMID: 1351412.

- ↑ Kido A, Miyake M, Akagi T, Ikeda HO, Kameda T, Suda K, Hasegawa T, Hiragi S, Yoshida S, Tsujikawa A, Tamura H, Kawakami K. Association between topical β-blocker use and asthma attacks in glaucoma patients with asthma: a cohort study using a claims database. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022 Jan;260(1):271-280. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05357-z. Epub 2021 Aug 9. PMID: 34370066.

- ↑ Schoene RB, Abuan T, Ward RL, Beasley CH. Effects of topical betaxolol, timolol, and placebo on pulmonary function in asthmatic bronchitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984 Jan;97(1):86-92. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90450-1. PMID: 6141730.

- ↑ Adkins JC, Balfour JA. Brimonidine. A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical potential in the management of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Drugs Aging. 1998 Mar;12(3):225-41. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199812030-00005. PMID: 9534022.

- ↑ Li T, Lindsley K, Rouse B, Hong H, Shi Q, Friedman DS, Wormald R, Dickersin K. Comparative Effectiveness of First-Line Medications for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2016 Jan;123(1):129-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.005. Epub 2015 Oct 31. PMID: 26526633; PMCID: PMC4695285.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Zhang L, Weizer JS, Musch DC. Perioperative medications for preventing temporarily increased intraocular pressure after laser trabeculoplasty. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb 23;2(2):CD010746. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010746.pub2. PMID: 28231380; PMCID: PMC5477062.

- ↑ Adkins JC, Balfour JA. Brimonidine. A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical potential in the management of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Drugs Aging. 1998 Mar;12(3):225-41. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199812030-00005. PMID: 9534022.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Walters TR. Development and use of brimonidine in treating acute and chronic elevations of intraocular pressure: a review of safety, efficacy, dose response, and dosing studies. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996 Nov;41 Suppl 1:S19-26. doi:

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Cantor LB. Brimonidine in the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2006 Dec;2(4):337-46. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.2006.2.4.337. PMID: 18360646; PMCID: PMC1936355.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 BECKER B. The mechanism of the fall in intraocular pressure induced by the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, diamox. Am J Ophthalmol. 1955 Feb;39(2 Pt 2):177-84. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(55)90022-2. PMID: 13228563.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. Glaucoma and the applications of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Subcell Biochem. 2014;75:349-59. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7359-2_17. PMID: 24146387.

- ↑ Maren TH, Jankowska L, Sanyal G, Edelhauser HF. The transcorneal permeability of sulfonamide carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and their effect on aqueous humor secretion. Exp Eye Res. 1983 Apr;36(4):457-79. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(83)90041-6. PMID: 6852128.

- ↑ Lusthaus JA, Goldberg I. Brimonidine and brinzolamide for treating glaucoma and ocular hypertension; a safety evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017 Sep;16(9):1071-1078. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2017.1346083. Epub 2017 Jul 6. PMID: 28656780.

- ↑ Faiq MA, Wollstein G, Schuman JS, Chan KC. Cholinergic nervous system and glaucoma: From basic science to clinical applications. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019 Sep;72:100767. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.06.003. Epub 2019 Jun 23. PMID: 31242454; PMCID: PMC6739176.

- ↑ Diniz Filho A, Cronemberger S, Mérula RV, Calixto N. Plateau iris. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2008 Sep-Oct;71(5):752-8. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492008000500029. PMID: 19039479.

- ↑ Kita Y, Hollό G, Mochizuki T, Emoto Y, Kita R, Hirakata A. Effect of Topical Pilocarpine Instilled Before Laser Peripheral Iridotomy on Regional Iris Thickness in Primary Angle Closure Disease: A Swept-Source Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography Pilot Study. Semin Ophthalmol. 2023 Aug;38(6):579-583. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2023.2169580. Epub 2023 Jan 30. PMID: 36715463.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Wu J, Wei J, Chen H, Dang Y, Lei F. Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitors for the Treatment of Glaucoma. Curr Drug Targets. 2024;25(2):94-107. doi: 10.2174/0113894501286195231220094646. PMID: 38155465; PMCID: PMC10964082.

- ↑ Bacharach J, Dubiner HB, Levy B, Kopczynski CC, Novack GD; AR-13324-CS202 Study Group. Double-masked, randomized, dose-response study of AR-13324 versus latanoprost in patients with elevated intraocular pressure. Ophthalmology. 2015 Feb;122(2):302-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.08.022. Epub 2014 Sep 27. PMID: 25270273.

- ↑ Serle JB, Katz LJ, McLaurin E, Heah T, Ramirez-Davis N, Usner DW, Novack GD, Kopczynski CC; ROCKET-1 and ROCKET-2 Study Groups. Two Phase 3 Clinical Trials Comparing the Safety and Efficacy of Netarsudil to Timolol in Patients With Elevated Intraocular Pressure: Rho Kinase Elevated IOP Treatment Trial 1 and 2 (ROCKET-1 and ROCKET-2). Am J Ophthalmol. 2018 Feb;186:116-127. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.11.019. Epub 2017 Dec 1. PMID: 29199013.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Walters TR, Ahmed IIK, Lewis RA, Usner DW, Lopez J, Kopczynski CC, Heah T; MERCURY-2 Study Group. Once-Daily Netarsudil/Latanoprost Fixed-Dose Combination for Elevated Intraocular Pressure in the Randomized Phase 3 MERCURY-2 Study. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2019 Sep-Oct;2(5):280-289. doi: 10.1016/j.ogla.2019.03.007. Epub 2019 Mar 28. PMID: 32672669.

- ↑ Van de Velde S, Van Bergen T, Vandewalle E, Kindt N, Castermans K, Moons L, Stalmans I. Rho kinase inhibitor AMA0526 improves surgical outcome in a rabbit model of glaucoma filtration surgery. Prog Brain Res. 2015;220:283-97. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.04.014. Epub 2015 Jun 30. PMID: 26497796.

- ↑ Okumura N, Kinoshita S, Koizumi N. Application of Rho Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Corneal Endothelial Diseases. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:2646904. doi:10.1155/2017/2646904

- ↑ Yan J, Xiong X, Shen J, Huang T. The use of fixed dose drug combinations for glaucoma in clinical settings: a retrospective, observational, single-centre study. Int Ophthalmol. 2022 Mar;42(3):945-950. doi: 10.1007/s10792-021-02076-6. Epub 2021 Oct 12. PMID: 34635957.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Fechtner RD, Realini T. Fixed combinations of topical glaucoma medications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004 Apr;15(2):132-5. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200404000-00013. PMID: 15021225.

- ↑ Higginbotham EJ, Hansen J, Davis EJ, Walt JG, Guckian A. Glaucoma medication persistence with a fixed combination versus multiple bottles. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009 Oct;25(10):2543-7. doi: 10.1185/03007990903260129. PMID: 19731993.

- ↑ Boyle JE, Ghosh K, Gieser DK, Adamsons IA. A randomized trial comparing the dorzolamide-timolol combination given twice daily to monotherapy with timolol and dorzolamide. Dorzolamide-Timolol Study Group. Ophthalmology. 1998 Oct;105(10):1945-51. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)91046-6. PMID: 9787368.

- ↑ Konstas AG, Schmetterer L, Katsanos A, Hutnik CML, Holló G, Quaranta L, Teus MA, Uusitalo H, Pfeiffer N, Katz LJ. Dorzolamide/Timolol Fixed Combination: Learning from the Past and Looking Toward the Future. Adv Ther. 2021 Jan;38(1):24-51. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01525-5. Epub 2020 Oct 27. PMID: 33108623; PMCID: PMC7854404.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Frampton JE. Topical brimonidine 0.2%/timolol 0.5% ophthalmic solution: in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Drugs Aging. 2006;23(9):753-61. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623090-00005. PMID: 17020399.

- ↑ Greig SL, Deeks ED. Brinzolamide/brimonidine: a review of its use in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Drugs Aging. 2015 Mar;32(3):251-60. doi: 10.1007/s40266-015-0250-4. PMID: 25732405.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Lee JW, Ahn HS, Chang J, Kang HY, Chang DJ, Suh JK, Lee H. Comparison of Netarsudil/Latanoprost Therapy with Latanoprost Monotherapy for Lowering Intraocular Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2022 Oct;36(5):423-434. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2022.0061. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35989070; PMCID: PMC9582491.

- ↑ Stewart WC, Konstas AGP, Nelson LA, Kruft B. Meta-analysis of 24-Hour Intraocular Pressure Studies Evaluating the Efficacy of Glaucoma Medicines. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1117-1122.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.004

- ↑ Li T, Lindsley K, Rouse B, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of First-Line Medications for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(1):129-140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.005

- ↑ Liu JHK, Kripke DF, Weinreb RN. Comparison of the nocturnal effects of once-daily timolol and latanoprost on intraocular pressure. Am J Ophthalmology. 2004;138(3):389-395. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.022

- ↑ Zhang X, Vadoothker S, Munir WM, Saeedi O. Ocular Surface Disease and Glaucoma Medications. Eye & Contact Lens: Science & Clinical Practice. 2019;45(1):11-18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/icl.0000000000000544

- ↑ Leek JC, Arif H. Pregnancy medications. StatPearls. Published July 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507858/