Salzmann Nodular Degeneration

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Salzmann nodular degeneration (SND) is a slowly progressive condition in which gray, white, or bluish nodules measuring 1–3 mm are seen anterior to Bowman membrane in the cornea, usually bilaterally.[1][2][3] These elevated nodules can be located near the limbus or in the mid-peripheral cornea.[4]

Etiology

No specific causal etiology has been described to date. Anecdotal evidence suggests that SND can occur following chronic corneal disorders; however, many cases appear to be idiopathic, arising in patients with no history of keratitis.[5][6] Genetic causes have also been described.[4]

Risk Factors

While meibomian gland dysfunction is the most common co-existent condition,[7] SND has been noted in patients with a history of ocular surface disease, including phlyctenulosis, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, interstitial keratitis, trachoma, scarlet fever, measles, and other viral diseases, and has been described in association with Crohn's disease.[4][8] It can also occur in patients with chronically dry eyes, chronic blepharitis, trichiasis, and previous ocular trauma, and has been seen postoperatively after cataract removal.[6][3] Additional risk factors have been postulated, including contact lens use and peripheral vascularization of the cornea.[9]

Epidemiology

Anywhere from 72%–88% of SND cases occur in women.[10] It is most common in Caucasian women in the 6th decade of life, but can be seen in both males and females of all ages beginning near adolescence.[3][7] The disease is seen bilaterally in 58%–67% of cases.[3]

General Pathology

Typical signs on Hematoxylin and Eosin stain include an absent or broken Bowman membrane, a thinned epithelium overlying the nodules, and disorganized subepithelial collagen fibrils (Figure 1).[9][4][5]

In vivo confocal microscopy reveals a normal epithelium in the central cornea with rare sub-basal nerve fibers that display increased thickness and lack branching. Occasionally seen around these fibers are reflective cellular elements. Nerve fibers in the corneal stroma are also abnormal, in that their branches are very thick and tortuous with highly reflective segments and contain “tracts with granular aspect.”[3] These abnormal stromal nerves resemble regenerating nerves that can be seen after penetrating keratoplasty.[11] Deep stroma and endothelial components do not appear to be altered. The peripheral zone of Salzmann nodules displays basal epithelial cells that appear abnormally elongated. Highly reflective structures (representing activated keratocytes) are present in both the peripheral zone and in the subepithelial stroma of the central portion of the nodules.[1][12]

Light microscopy (Figure 1) reveals dense deposits of hyalinized, irregularly arranged collagen fibers anterior to a fragmented and sometimes absent Bowman membrane.[1][12] The tissue overlying the Salzmann nodules displays an attenuated epithelium containing only 1 or 2 layers of discontinuous, elongated basal cells, in addition to 2–3 more hyperchromatic layers above it.[1][12] The corneal stroma contains unevenly distributed keratocytes and disorganized collagen bundles. The keratocytes seen in the nodular stroma have not been shown to be mitotically active; rather, they resemble activated fibroblasts or myofibroblasts of the anterior stroma during corneal repair.[1] Morphometric analysis yields a thinned corneal epithelium (2- to 4–fold) overlying the Salzmann nodules.[1]

The American Academy of Ophthalmology's Pathology Atlas contains a virtual microscopy image of SND.[13]

Pathophysiology

One hypothesis suggests that enzymatic destruction of the Bowman membrande results in migration and proliferation of keratocytes from the posterior stroma, resulting in secondary deposition of extracellular matrix components in nodular areas.[14]

Salzmann nodules consist of a hypercellular area of extracellular matrix seen between a thinned overlying corneal epithelium and a fragmented or absent Bowman membrane.[4][14] Cellular elements within these nodules stain with vimentin (similar to fibroblasts). The basal epithelial cells that overly the nodules stain negatively for matrix metalloproteinase-9 but positively for matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2).[14] MMP-2 is not normally expressed in terminally differentiated epithelia of the central cornea.[14] This protein has the ability to dissolve collagen type IV, which is the main component of the corneal epithelial basement membrane.[4] The expression of MMP-2 by the basal epithelial cells overlying Salzmann nodules suggests that these cells may be contributing to the destruction of the Bowman membrande, subsequently resulting in migration and proliferation of keratocytes and deposition of extracellular matrix in nodular areas. It has been hypothesized that MMP-2 overexpression in the basal epithelial cells overlying Salzmann nodules occurs by induction due to an elevating nodule[14]; however, it is unclear exactly what then could have caused the nodule to appear in the first place.

Immunohistochemical analysis of protein expression in the basal epithelial cells suggests that these cells have a high metabolic activity—a feature also seen in the transient amplifying epithelial cells of the limbus. This finding implicates the involvement of the epithelial cells in the formation of the subepithelial collagen elements seen in Salzmann nodules. This in turn correlates with the clinical association that has been described linking chronic ocular surface disease (affecting the corneal epithelium) with the development of SND.[4] Additionally, an autoimmune etiology has also been suggested in terms of SND pathogenesis.[6]

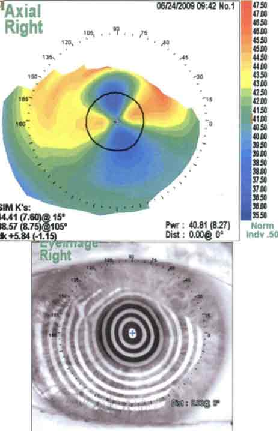

Regardless of the biochemical mechanisms responsible for the pathogenesis of this disease, SND can cause clinically apparent astigmatism due to the nature of its characteristic nodular pattern.[4]

Diagnosis

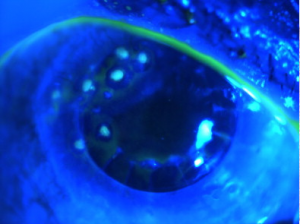

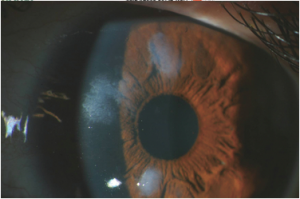

The diagnosis of SND is usually made clinically. A slit lamp exam can show the characteristic gray, white, or bluish nodules posterior to the corneal epithelium.[9] These nodules can occasionally stain with fluorescein (Figure 2).[3] Corneal topography can reveal significant irregular astigmatism occurring as a result of Salzmann nodules (Figure 3).[9]

Histopathology performed on a surgical specimen can reveal stromal scarring, a thin overlying corneal epithelium, and a fragmented or absent Bowman’s layer (see Figure 1).[4][9]

History and Physical Examination

These patients usually present with gradual, painless loss of vision—both near-vision and distance-vision.[9] They may or may not have a history of chronic ocular surface disease such as that described above. Patients may also complain of a “foreign body sensation” on the surface of their eye.[4] Slit lamp exam can reveal white to bluish-grey nodules within the cornea (Figure 4).[4]

Symptoms

Decreased visual acuity, epiphora, photophobia and chronic foreign body sensation are the most commonly seen symptoms.[4] However, in about 15% of cases SND can be asymptomatic.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

Corneal scarring and astigmatism, spheroidal degeneration, and corneal abrasion can present with a similar deterioration of visual acuity.[9]

Peripheral hypertrophic subepithelial corneal degeneration (PHSCD) is often considered a subtype of Salzmann nodular degeneration (SND), but is distinct in several important ways. PHSCD has been most commonly described in Caucasian women aged 40–65 years, often with a history of ocular surgery, ocular surface disease, or contact lens use. The condition is typically bilateral and symmetric.[15]

PHSCD can be distinguished from SND by its more peripheral, circumferential fibrotic subepithelial lesions, with relative sparing of the central cornea. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrates subepithelial fibrosis without associated inflammation.[15]

Management of PHSCD depends on disease severity and symptom burden, with conservative treatment using lubrication for mild cases and surgical intervention reserved for more advanced disease associated with decreased visual acuity or significant irregular astigmatism.[15]

Management

To date, no cases of spontaneous resolution of SND have been reported. Treatment involves either medical management or surgical removal of the nodular lesions, depending on the patient’s clinical picture.[4] Surgical treatment (when indicated) usually results in rapid improvement of visual acuity.[4] Conservative treatment can involve management of the potentially underlying etiology (if known).[9] Medical management, which successfully treats most patients, may include ocular lubrication, steroid eye drops, warm compresses and proper eyelid hygiene.[3]

Indications for surgical treatments include ocular discomfort (i.e,, usually a “foreign body sensation”) or reduced visual acuity due to irregular astigmatism.[9] Superficial keratectomy successfully results in improved visual acuity in 90% of cases.[7] Recurrences are very common (about 22% after a mean follow-up time of 61 months)[7]; however, recurrences significant enough to impact vision have only been reported in 5%–20% of cases.[9]

If visually significant anterior stromal haze persists after superficial keratectomy, phototherapeutic keratectomy can be used as an adjunct therapy.[9] In some cases, superficial keratectomy can easily separate elevated nodular tissue from the corneal surface, leaving the Bowman membrane (where present) untouched; subsequent phototherapeutic keratectomy is then performed in order to create a homogeneous cornea.[5] Recurrence is rare in these situations. Phototherapeutic keratectomy can be performed with or without topical mitomycin-C; however, this procedure can induce a myopic shift.[3][5]

Other cases, which are often complicated with major peripheral vascularization, involve difficult-to-remove nodules, with subsequent deeper defects in the Bowman membrane and the superficial stroma after superficial keratectomy. These situations may require several masking or laser ablation procedures following keratectomy in order to create a smooth surface. Done properly, laser ablation usually prevents the need for lamellar and penetrating keratoplasty, though recurrences occur more frequently.[5]

Anterior lamellar keratoplasty is rarely required. Generally, it is only performed when Salzmann nodules are seen extending to or past the mid-stroma.[3] However, keratoplasty may not necessarily be a perfect cure. A 1990 study by Severin and Kirchoff demonstrated that not only can a late epithelial immune response be observed within 18 months of keratoplasty, but the procedure can also be followed by evidence of incomplete re-epithelization and the development of superficial cloudy opacities within 2.5–9 years.[10]

Complications

The subepithelial nodules that characterize SND can irritate the ocular surface, resulting in secondary recurrent corneal erosions, photophobia, blepharospasm, and tearing.[16] The nodules themselves can also create a relatively steepened mid-peripheral cornea and a flatter central cornea, leading to hyperopic visual changes.[16] It has been demonstrated that SND causes more significant astigmatism in patients whose disease affects multiple corneal quadrants; consequently, these patients are more likely to require surgical treatment.[7] Peripheral corneal vascularization can also occur in 7%–31% of patients[3][17]; however, this complication could actually be a result of the original pathology causing SND rather than being due to SND itself.[3] This is a potentially important complication since it is more commonly associated with nodules that are more difficult to remove.[5]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Roszkowska AM, Aragona P, Spinella R, et al. Morphologic and confocal investigation on Salzmann nodular degeneration of the cornea. Cornea. 2011;52(8):5910-5919.

- ↑ Salzmann M. Uebereine Abart der knoetchen foermigen Hornhaut dystrophie. [Article in German] Zeitschriftfuer Augenheilk. 1925;57:92-99.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Hamada S, Darrad K, McDonnell P. Salzmann’s nodular corneal degeneration: clinical findings, risk factors, prognosis and the role of previous contact lens wear. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2011;34(4):173-178.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 Eberwein P, Hiss S, Auw-Haedrich C, et al. Epithelial marker expression in Salzmann nodular degeneration shows characteristics of limbal transient amplifying cells and alludes to an involvement of the epithelium in its pathogenesis. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2010;88(5):e184-e189.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Das S, Link B, Seitz B. Salzmann's nodular degeneration of the cornea: a review and case series. Cornea. 2005;24(7):772-777.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Yoon KC, Park YG. Recurrent Salzmann’s nodular degeneration. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2003;47(4):401-404.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Graue-Hernández EO, Mannis MJ, Eliasieh K, et al. Salzmann nodular degeneration. Cornea. 2010;29(3):283-289.

- ↑ Lange AP, Bahar I, Sansanayudh W, et al. Salzmann nodules—a possible new ocular manifestation of Crohn’s disease: a case report. Cornea. 2009;28(1):85-86.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Carroll JN, Maltry AC, Kitzmann AS. Salzmann’s nodular corneal Degeneration: 62-year-old woman presents with 3 years of progressive decrease in vision. EyeRounds.org. Published September 9, 2013. Accessed May 8, 2025. http://EyeRounds.org/cases/180-salzmann-nodular-corneal-degeneration.htm.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Severin M, Kirchhof B. Recurrent Salzmann’s nodular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1990;228(2):101-104.

- ↑ Müller LJ, Pels L, Vrensen GF. Ultrastructural organization of human corneal nerves. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:476-488.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Meltendorf C, Bühren J, Bug R, et al. Correlation between clinical in vivo confocal microscopic and ex vivo histopathologic findings of Salzmann nodular degeneration. Cornea. 2006;25(6):734-738.

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ocular pathology atlas. Published September 16, 2016. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.aao.org/resident-course/pathology-atlas.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Stone D, Astley R, Shaver R, et al. Histopathology of Salzmann nodular corneal degeneration. Cornea. 2008;27(2):148-151.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Moshirfar M, Moin KA, Ronquillo Y. Peripheral hypertrophic subepithelial corneal degeneration. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. Updated October 6, 2024. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK607997/

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Khaireddin R, Katz T, Baile R, et al. Superficial keratectomy, PTK, and mitomycin C as a combined treatment option for Salzmann’s nodular degeneration: a follow-up of eight eyes. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(8):1211-1215.

- ↑ Farjo AA, Halperin GI, Syed N, et al. Salzmann’s nodular corneal degeneration clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes. Cornea. 2006;25(1):11-15.