Veterinary Ophthalmology

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

The eye is composed of specialized structures ranging from the anterior segment and ocular surface to the posterior segment with the retina and optic nerve, all of which have been shaped through evolutionary selection.The ecological roles of species, as fundamental as predator versus prey, have been critical in shaping the development of their visual systems. For example, carnivores typically exhibit a higher degree of orbital convergence to enhance binocular vision, whereas herbivores often have a lower degree of convergence to maximize panoramic fields of view (as described below). One of the goals of this article is to provide insights into the anatomical variations of the eye across species and highlight how these differences compare with human ocular anatomy.

The understanding of veterinary ophthalmology lends a hand to challenging human ophthalmic diseases and can give human ophthalmologists insight on mechanisms of natural animal models. Various animals species that veterinary ophthalmologist evaluate encompasses a wide range of disease that is unique but at the same time, strikingly similar. Examples, include dogs with keratoconjunctivitis sicca, glaucoma, and corneal ulceration amongst the most common disorders, while cats frequently present with herpesvirus keratitis or eosinophilic keratitis. Horses are particularly prone to recurrent uveitis and vision-threatening corneal trauma. These conditions often parallel human diseases, and one goal of this article is to highlight the physiological and pathological processes observed in animal species and demonstrate how they can inform the treatment of similar ocular conditions in humans.

Anterior Segment & Ocular Surface

1. Tear Film Composition and Dry Eye Disease

The human tear film is a trilaminar structure composed of an outer lipid layer (from meibomian glands), a middle aqueous layer (from lacrimal glands), and an inner mucin layer (from conjunctival goblet cells). Dysfunction arises from deficiencies or qualitative changes in any layer, leading to instability, increased evaporation, hyperosmolarity, and inflammation, which are hallmarks of Dry Eye Disese. Porcine and feline models have been shown to suffer similar tear film dysfunctions as humans while also possessing the most similar non-primate tear film protein composition, making them an ideal translational model. However, another mammal, the camel, possesses a unique tear-film adaptation which is useful to understand. [1][2][3]

Camels are adapted to dry environments, from their iconic humps to their eyes, which possess one extra set of lashes (two total) and two additonal eyelids (three total) as compared to humans. The composition of their tear film in terms of the proteins found are varied when compared to humans due to the environment selection of their natural habitats. Camels do not develop diseases arising from tear film layer dysfunction, such as dry eye disease, similar to what is observed in humans, pigs, and cats. Camel tear film possesses unique adaptive features, including higher mineral content, superior ferning patterns, and the presence of specific proteins such as the VMO1 homolog. VMO1 homolog protein is though to enhanced stability and protection against ocular surface dryness, particularly in arid environments. Homologous VMO1 was present in camel and sheep tears but not in human tears. Their tear mineral composition was even found to be superior to one of the leading artificial tear brands. These adaptations are thought to prevent the development of tear film instability and associated ocular surface disease.[4][5]

2. Optical Lens Tinting and Wavelength-Specific Filters

In humans, artificial lens tinting, such as blue-blocking intraocular lenses, spectacle filters, or contact lens tints, modifies the transmission of specific wavelengths to the retina. These interventions can reduce glare, improve contrast sensitivity, and protect against phototoxicity, but may also alter color perception and circadian regulation. Mechanistically, these filters act by absorbing or reflecting selected wavelengths, thereby shifting the spectral composition of light reaching the photoreceptors. In birds, wavelength-specific filtering is achieved naturally by retinal oil droplets located within cone photoreceptors. These droplets contain carotenoid pigments that selectively absorb short wavelengths, narrowing the spectral sensitivity of each cone subtype and enhancing color discrimination. The oil droplets also function as microlenses, increasing refractive index and channeling filtered light into the photoreceptor’s outer segment, compensating for light loss due to filtering and optimizing spectral tuning for ecological needs. This natural adaptation provides birds with tetrachromatic vision and superior color constancy, far exceeding the spectral filtering capabilities of artificial human lens tints. [6][7][8]

3. Lens Accommodation Mechanisms

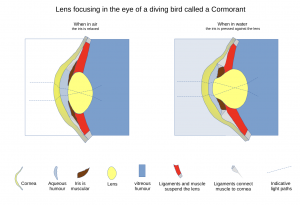

In humans, accommodation is achieved by contraction of the ciliary muscle, which relaxes zonular tension and allows the crystalline lens to become more convex, increasing refractive power for near vision. With age, lens elasticity decreases, leading to presbyopia, a progressive loss of accommodation. The mechanism is limited to lenticular deformation, and the ciliary muscle does not directly alter corneal curvature. In contrast, birds and reptiles possess dual accommodation mechanisms. The ciliary muscle is anatomically divided, with one portion deforming the lens and another actively changing the corneal radius of curvature. This allows rapid and extensive shifts in focal length, supporting high visual acuity and dynamic focusing in diverse environments. Certain birds employ both corneal and lenticular accommodation, with species-specific variation in the relative contribution of each mechanism. Cormorants are known for their remarkable accommodative ability, which is achieved through a highly pliable lens and powerful intraocular muscles that allow rapid and substantial changes in lens shape to compensate for the loss of corneal refractive power underwater. This change compensates for the dramatic loss of corneal refractive power underwater, as water and the cornea have similar refractive indices, rendering the cornea nearly optically neutral in this environment. [9] Comparative analysis highlights the evolutionary specialization of avian and reptilian eyes for spectral discrimination and accommodation, providing translational insights for artificial lens design and presbyopia management in humans. [10][11][12]

Posterior Segment & Retinal Function

1. Foveal Specializations in Birds of Prey, Dogs, and Humans

Humans and most primates have one fovea located centrally. Birds of prey such as the Australian kingfishers, eagles, and tree swallows have two foveae in each eye. These are called bifoveate birds, as they have one centrally located and one temporally located fovea, each providing a unique evolutionary advantage. In bifoveate birds, the central fovea region had a higher density of ganglion cells/mm² than the temporal fovea region. The central fovea of these birds is for high visual acuity and fixation on distant objects. The temporal fovea are presumed to be used for near object vision. These bird of prey can spot a their prey with the higher-acuity nasal fovea and quickly switch to the temporal fovea when attacking their prey underwater. Eagles have a photoreceptor concentration in the fovea that exceeds 1 million per square millimeter, which is substantially higher than the approximately 200,000 photoreceptors per square millimeter found in the human fovea. [13]

Owls possess a temporally placed, single deep fovea that is morphologically distinct from the foveae of many other birds. In owls, the fovea is located in the temporal retina and is characterized by a pronounced invagination, often described as "convexiclivate," which is deeper than that found in most diurnal raptors and other avian species. [14] This is associated with a high density of retinal ganglion cells and photoreceptors meaning they are thought to have enhanced spatial resolution in the region of highest visual acuity. Additionally, these temporally placed deep foveas are so deep that it can effectively act as a lens like structure and provide refracting capabilities to enlarge the image on the photoreceptor layer. Owls have a more temporally placed, single deep fovea – so deep that it provides refractive capabilities. It effectively is acting as a lens-like structure that modifies the path of incoming light, potentially enlarging or focusing the image on the photoreceptor layer. This convexiclivate fovea adds 11% magnification.

The area centralis is a specialized region in the retina of many vertebrates, including canines, that serves as the center of highest visual acuity. It is functionally analogous to the fovea of humans but has key differences. It was previously thought that high cone densities are unique to primates. The canine area centralis contains a small region with densely packed cones. Unlike the primate fovea, the canine fovea-like area lacks the excavation of inner retinal layers (no foveal pit), resembling the rare human condition called fovea plana, where high cone density exists without a pit. Dogs with mutations in BEST1 and RPGR genes develop early retinal abnormalities specifically in the fovea-like area, similar to degenerative disease targeting the macula in humans. [15]

2. Retinal Vascularization

In the healthy human eye, the retina has two vascular supplies, the central retinal artery (CRA) and the posterior ciliary arteries or the chorodial circulation. The human eye’s vasculature resembles a reticular spider’s web, comprised of superficial vessels evenly distributed and capillaries providing a regular distribution around the foveal avascular zone (FAZ). Notably, the fovea appears as an avascular area, absent of capillaries, as does the far periphery. This distribution allows for the simultaneous transmission of light through the retinal layers and oxygen exchange through differences in partial pressures and response to things like carbon dioxide and other metabolites. [16]

Interestingly the avian eye provides a different solution to oxygenation of retinal tissues in a unique structure called the pecten oculi. While the retina remains entirely avascular, the pecten oculi is a highly vascularized structure found in the eyes of birds that is widely believed to provide the same oxygenation and waste removal as human choroidal and retinal vascularization. However, its structure suggests that it serves additional functions. While highly vascularized, it is also a black pleated structure extending from the retina with an origin just behind the optic disc into the vitreous body. Some studies suggest it plays a variety of vital roles in bird vision, including reducing intraocular glow, regulating pressure, supporting retinal nutrition, maintaining the blood-retina barrier, absorbing light, aiding orientation, warming the eye, stabilizing the vitreous body, and enhancing vision during saccadic eye movements. Furthermore, the exact physiology of the structure seems to additionally vary between species at least in part based upon the phylogeny, differing between diurnal and nocturnal species. [17][18]

3. Photoreceptor Degeneration and Retinal Dystrophies

Inherited retinal disease (IRD) is a major cause of blindness in working-age adults and often begins early, causing significant personal and economic impact. Diagnosis is difficult due to broad genetic and phenotypic diversity, with over 60 genes and at least 50 phenotypes implicated, leaving many patients undiagnosed even after genome sequencing. Accurate clinical and genetic testing is critical for prognosis, counseling, and eligibility for emerging therapies. Advances in sequencing, imaging, and functional testing have improved accuracy, particularly for common IRD genes such as ABCA4, USH2A, RPGR, PRPH2, and BEST1. While gene augmentation shows promise, challenges remain, including immune responses to viral vectors. Newer approaches such as CRISPR-based editing, base and prime editing, and nanotechnology delivery offer potential for safer and more effective treatments. [19][20][21]

IRDs naturally occurring in cats and dogs provide crucial models for human IRDs, as these animals share similar disease phenotypes and eye structures—such as a high-acuity retinal region comparable to the human macula—offering insights beyond rodent models. Established feline and canine models exist for conditions like Leber congenital amaurosis, retinitis pigmentosa (RP), achromatopsia, and Stargardt disease. Advances in genome editing technologies in these species are enabling the creation of specific IRD models, further advancing research and therapeutic development. [22]

Progressive retinal atrophy (PRA), a similar condition to retinitis pigmentosa (RP), affects dogs—often in specific breeds due to inbreeding—and shares clinical features, genetics, and disease progression with human RP. For example, Miniature Schnauzers exhibit two forms of PRA linked to different genetic loci, including a recessive regulatory variant that increases expression of genes (EDN2 and COL9A2) associated with retinal degeneration. This discovery marks one of the first regulatory variants implicated in retinal disease and establishes a valuable canine model for studying retinal biology and gene regulation. [23][24]

In addition, studies on two dog models of RP caused by PDE6A and CNGB1 mutations assessed retinal dysfunction using electroretinogram (ERG) responses and tested AAV-mediated gene augmentation therapy. PDE6A-mutant dogs showed severe rod dysfunction with minor cone impairment, while CNGB1-mutant dogs retained some rod and normal cone function. Gene therapy substantially improved rod function and sensitivity in both models, demonstrating effective restoration of normal photoreceptor activity and highlighting the promise of gene augmentation as a treatment for RP. [25]

4. Scotopic vision

From a basic anatomic perspective, layers of rods and cones exist in an outer layer of the retina where rods use Vitamin A to metabolize a component of rhodopin, a light-sensitive pigment. Understandably, therefore, Vitamin A deficiency can result in “night-blindness.” While human rods and cones contribute heavily to our ability to adapt under different lighting conditions, multiple studies suggest a decline in this adaptation in our photoreceptors, particularly under low-light and as we age. [26] Reduced night vision can be the primary symptom for an array of both inherited and acquired retinal diseases (i.e. cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, vitamin A deficiency, refractive error, etc.), and yet, at baseline, a large divide exists between the adaptation of human eyes to low-light and the adaptations of nocturnal animals.

Adaptation to low light in nocturnal animals is often achieved with a structure known as the Tapetum Lucidum, a light-reflective tissue in the eyes of many animals. This structure is found behind the photoreceptors in the eyes of certain fish and land animals. Its role is to bounce incoming light back through the retina, effectively giving photons another opportunity to be detected and improving vision in low-light conditions. [27] [28]Among vertebrates and arthropods, tapetal structures show significant diversity in form, composition, and organization—suggesting that they have evolved independently multiple times. Interestingly, no such structure has been identified in cephalopods (octopuses, squid, etc), despite their possession of camera-like eyes; unlike vertebrates, their photoreceptors face forward. This leads to the hypothesis that the tapetum lucidum evolved in vertebrates to compensate for the limitations of their inverted retinal arrangement. Horses possess a fibrous tapetum strategically arranged to enhance night-time vision by efficiently reflecting blue-green light back to rod photoreceptors. Its structure—especially the thick, unpigmented horizontal band paired with the visual streak—supports both sensitivity in dim light and visual resolution under brighter conditions. Other adaptations include that of müller cells in mammalian retinas which act as optical fibers that guide light to photoreceptors, but it remains unclear if they serve a similar function in nonmammalian species. One study found that they likely aided in light transmission through the retina, increasing visual sensitivity in dim environments. [29][30]

Optic Nerve & Neuro-Ophthalmology

1. Pupillary Light Reflex and Neurologic Assessment

The pupil is an aperture of the eye that allows light to reach retinal photoreceptors. It is controlled by the iris, composed of the sphincter pupillae and dilator pupillae muscles under discrete autonomic control. The sphincter pupillae receives parasympathetic innervation from the Edinger-Westphal nucleus via the oculomotor nerve and short ciliary nerves, mediating constriction. [31] The dilator pupillae receives sympathetic innervation from the superior cervical ganglion through the long ciliary nerves to dilate the pupil. The pupillary light reflex is a brainstem-mediated response where retinal ganglion cells transmit signals via the optic nerve to the pretectal nucleus, then bilaterally to the Edinger-Westphal nucleus. [32][33] This reflex provides an objective measure of optic and oculomotor nerve function; light in one eye produces direct and consensual constriction if pathways are intact. Loss of the reflex indicates brainstem dysfunction and aids in prognostication after injury. [34]

In other mammalian species such as cats and dogs, the neurological pathway of the pupillary light reflex is similar; however, the amplitude of the constriction can differ based on the intensity of the stimulus when compared to humans. [35] [36] In reptiles, turtles have irides that are also innervated by the oculomotor nerve, but their pupillary light response is substantially more sluggish with constriction and relaxation developing over minutes. [37] This sluggish response could be attributed to the central processing or photoreceptive mechanism within their retina. While other species have smooth muscles for iridies, the iris muscles are striated in avian species allowing for a more voluntary control in pupil size. These irides are controlled through nicotinic cholinergic receptors rather than muscarinic cholinergic receptors as seen in mammals. This study has shown that male pigeons constricted their pupils during courtship, but not in other waking behaviors suggesting a social component behind voluntary pupillary constriction. [38]

2. Color Vision

The trichromatic system in human vision is mediated by three distinct types of cone photoreceptors in the retina: L-cones (long-wavelength sensitive, peak sensitivity around 552–557 nm), M-cones (medium-wavelength sensitive, peak around 530 nm), and S-cones (short-wavelength sensitive, peak around 426 nm). Each cone type expresses a unique opsin protein, conferring maximal sensitivity to a specific region of the visible spectrum, which broadly corresponds to red (L), green (M), and blue (S) light, respectively. Some humans are dichromats like non-primate mammals ("red-green color blind"). It is thought that the human photoreceptors were simplified due to evolutionary pressures such as the ‘nocturnal bottleneck’ in which early mammals prioritized low light vision. Primitive vertebrates such as lampreys have five cone-like photoreceptors. Each receptor type also contains a different visual pigment (opsin gene), namely LWS, SWS1, SWS2, RhA, and RhB. The addition of these receptors makes their vision pentachromatic and thus enhances their spectral filters for tuning the light. Advantageous for prey detection (distinguishing prey from background clutter, even when prey and background have similar luminance but different spectral properties), predator avoidance (rapid recognition of predators against variable backgrounds), and mate selection in bright environments (assessing mate quality based on coloration). [39][40][41]

3. Glaucoma Pathophysiology and Optic Nerve Damage

In humans, glaucoma is an insidious disease and one of the many leading causes of blindness. The pathophysiological mechanism remains elusive, but one leading theory involves a mechanical process where increased intraocular pressure induces posterior thinning and malformation of the lamina cribrosa. [42] This lamina cribrosa is a collagenous structure within the posterior sclera surrounding the optic nerve head, where retinal ganglion axons exit the eye. This mechanical process will disrupt axonal transport of neurotrophic factors in the retinal ganglion cell layer, ultimately contributing to axonal degeneration and optic nerve head damage. [43]

When compared to other species, the lamina cribrosa of cats is also robust and collagenous, which closely resembles the human counterpart, making it a common animal model used to study glaucomatous progression in humans. [44] Interestingly, dogs also have a similar thickness of their lamina cribrosa when compared with humans; however, the distance between the anterior lamina cribrosa and the subarachnoid space was shown to be greater in dogs than in humans, and the pia mater tends to be thinner. [45] This significant difference in distance could play a role in changing the pressure gradient and the progression of glaucoma. In canine studies, glaucoma advances more rapidly with significant retinal ganglion cell loss and optic nerve damage within months to a few years. [46] In contrast, horses have less developed and a more primitive arrangement of collagenous fibers and glial cells in their lamina cribrosa. [47] This structural difference seen in horses can contribute to reduced metabolic support predisposing them to more diffuse axonal injury when compared to humans.

Ocular Motility / Binocular Vision

Orbital Convergence

Orbit convergence is the degree to which the orbits face in the same direction. It is the angle of the orbit relative to the anterior–posterior axis of the skull.[48] Forward-facing orbits increase orbital convergence, creating greater binocular overlap. This enhances depth perception and supports high visual acuity by allowing more precise integration of images from both eyes.[49] Side-facing orbits have decreased orbital convergence, allowing for a wider field of view. [50]

- High orbital convergence species include more carnivore species such as primates, crocodiles, lions, and sharks.

- Low orbital convergence species include more herbivores such as rabbits, hares, deer, and camels.

References

- ↑ Pflugfelder SC, Stern ME. Biological functions of tear film. Exp Eye Res. 2020;197:108115. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2020.108115

- ↑ Simin Masoudi,Biochemistry of human tear film: A review,Experimental Eye Research,Volume 220, 2022,109101,ISSN 0014-4835,

- ↑ Shamsi FA, Chen Z, Liang J, et al. Analysis and comparison of proteomic profiles of tear fluid from human, cow, sheep, and camel eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(12):9156-9165. Published 2011 Nov 25. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8301

- ↑ Analysis and Comparison of Proteomic Profiles of Tear Fluid From Human, Cow, Sheep, and Camel Eyes. Shamsi FA, Chen Z, Liang J, et al.Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52(12):9156-65. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8301.

- ↑ Structure and Microanalysis of Tear Film Ferning of Camel Tears, Human Tears, and Refresh Plus. Am M, Ra F, El-Naggar AH, Tm A. Molecular Vision. 2018;24:305-314 Comparison of Camel Tear Proteins Between Summer and Winter. Chen Z, Shamsi FA, Li K, et al. Molecular Vision. 2011;17:323-31.

- ↑ Oil Droplets of Bird Eyes: Microlenses Acting as Spectral Filters. Stavenga DG, Wilts BD. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2014;369(1636):20130041. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0041.

- ↑ Avian Retinal Oil Droplets: Dietary Manipulation of Colour Vision?. Knott B, Berg ML, Morgan ER, et al. Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 2010;277(1683):953-62. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1805.

- ↑ Evolution, Development and Function of Vertebrate Cone Oil Droplets. Toomey MB, Corbo JC. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2017;11:97. doi:10.3389/fncir.2017.00097.

- ↑ Katzir G, Howland HC. Corneal power and underwater accommodation in great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis). J Exp Biol. 2003 Mar;206(Pt 5):833-41. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00142. PMID: 12547938.

- ↑ Visual Accommodation in Vertebrates: Mechanisms, Physiological Response and Stimuli. Ott M. Journal of Comparative Physiology. A, Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology. 2006;192(2):97-111. doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0049-6.

- ↑ The Quest for the Human Ocular Accommodation Mechanism. de Jong PTVM. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2020;98(1):98-104. doi:10.1111/aos.14194.

- ↑ A History of Studies of Visual Accommodation in Birds. Glasser A, Howland HC. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 1996;71(4):475-509. doi:10.1086/419554.

- ↑ Fite KV, Rosenfieldwessels S. Comparative study of deep avianfoveas . Brain Behav Evol. 1975 ; 12 : 97 - 115 .

- ↑ Lisney TJ, Iwaniuk AN, Bandet MV, Wylie DR. Eye shape and retinal topography in owls (Aves: Strigiformes). Brain Behav Evol. 2012;79(4):218-36. doi: 10.1159/000337760. Epub 2012 Jun 18. PMID: 22722085

- ↑ Beltran WA, Cideciyan AV, Guziewicz KE, et al. Canine retinahas a primate fovea- like bouquet of cone photoreceptors whichis affected by inherited macular degenerations. PLoS One.2014;9:e90390.

- ↑ Wright WS, Eshaq RS, Lee M, Kaur G, Harris NR. Retinal Physiology and Circulation: Effect of Diabetes. Compr Physiol. 2020 Jul 8;10(3):933-974. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c190021. PMID: 32941691; PMCID: PMC10088460.

- ↑ Abumandour MMA, Morsy K, Hanafy BG. Biological features of the pecten oculi of the European wild quail (Coturnix coturnix): Adaptative habits to Northern Egyptian coast with novel vision to its SEM-EDX analysis. Microsc Res Tech. 2022 Dec;85(12):3817-3829. doi: 10.1002/jemt.24236. Epub 2022 Oct 1. PMID: 36181442.

- ↑ Simon Potier, Mindaugas Mitkus, Almut Kelber, Visual adaptations of diurnal and nocturnal raptors,Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology,Volume 106, 2020,Pages 116-126, ISSN 1084-9521, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.05.004.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1084952119301004)

- ↑ Siying Lin, Sandra Vermeirsch, Nikolas Pontikos, Maria Pilar Martin-Gutierrez, Malena Daich Varela, Samantha Malka, Elena Schiff, Hannah Knight, Genevieve Wright, Neringa Jurkute, Mark J. Simcoe, Patrick Yu-Wai-Man, Mariya Moosajee, Michel Michaelides, Omar A. Mahroo, Andrew R. Webster, Gavin Arno, Spectrum of Genetic Variants in the Most Common Genes Causing Inherited Retinal Disease in a Large Molecularly Characterized United Kingdom Cohort, Ophthalmology Retina, Volume 8, Issue 7, 2024, Pages 699-709, ISSN 2468-6530, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2024.01.012.

- ↑ Schneider N, Sundaresan Y, Gopalakrishnan P, Beryozkin A, Hanany M, Levanon EY, Banin E, Ben-Aroya S, Sharon D. Inherited retinal diseases: Linking genes, disease-causing variants, and relevant therapeutic modalities. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2022 Jul;89:101029. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2021.101029. Epub 2021 Nov 25. PMID: 34839010.

- ↑ Carvalho C, Lemos L, Antas P, Seabra MC. Gene therapy for inherited retinal diseases: exploiting new tools in genome editing and nanotechnology. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne). 2023 Sep 19;3:1270561. doi: 10.3389/fopht.2023.1270561. PMID: 38983081; PMCID: PMC11182192.

- ↑ Petersen-Jones SM, Komáromy AM. Canine and Feline Models of Inherited Retinal Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2024 Feb 1;14(2):a041286. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a041286. PMID: 37217283; PMCID: PMC10835616.

- ↑ Bunel M, Chaudieu G, Hamel C, Lagoutte L, Manes G, Botherel N, Brabet P, Pilorge P, André C, Quignon P. Natural models for retinitis pigmentosa: progressive retinal atrophy in dog breeds. Hum Genet. 2019 May;138(5):441-453. doi: 10.1007/s00439-019-01999-6. Epub 2019 Mar 23. PMID: 30904946.

- ↑ Kaukonen M, Quintero IB, Mukarram AK, Hytönen MK, Holopainen S, Wickström K, Kyöstilä K, Arumilli M, Jalomäki S, Daub CO, Kere J, Lohi H; DoGA Consortium. A putative silencer variant in a spontaneous canine model of retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS Genet. 2020 Mar 9;16(3):e1008659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008659. PMID: 32150541; PMCID: PMC7082071.

- ↑ Pasmanter N, Occelli LM, Petersen-Jones SM. ERG assessment of altered retinal function in canine models of retinitis pigmentosa and monitoring of response to translatable gene augmentation therapy. Doc Ophthalmol. 2021 Oct;143(2):171-184. doi: 10.1007/s10633-021-09832-0. Epub 2021 Apr 5. PMID: 33818677; PMCID: PMC8509084.

- ↑ Jackson GR, Owsley C. Scotopic sensitivity during adulthood. Vision Res. 2000;40(18):2467-73. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00108-5. PMID: 10915886.

- ↑ Shinozaki A, Takagi S, Hosaka YZ, Uehara M. The fibrous tapetum of the horse eye. J Anat. 2013 Nov;223(5):509-18. doi: 10.1111/joa.12100. Epub 2013 Sep 15. PMID: 24102505; PMCID: PMC4399361.

- ↑ Zueva L, Zayas-Santiago A, Rojas L, Sanabria P, Alves J, Tsytsarev V, Inyushin M. Multilayer subwavelength gratings or sandwiches with periodic structure shape light reflection in the tapetum lucidum of taxonomically diverse vertebrate animals. J Biophotonics. 2022 Jun;15(6):e202200002. doi: 10.1002/jbio.202200002. Epub 2022 Mar 20. PMID: 35243792; PMCID: PMC9487202.

- ↑ Vee S, Barclay G, Lents NH. The glow of the night: The tapetum lucidum as a co-adaptation for the inverted retina. Bioessays. 2022 Oct;44(10):e2200003. doi: 10.1002/bies.202200003. Epub 2022 Aug 26. PMID: 36028472.

- ↑ Karl A, Agte S, Zayas-Santiago A, Makarov FN, Rivera Y, Benedikt J, Francke M, Reichenbach A, Skatchkov SN, Bringmann A. Retinal adaptation to dim light vision in spectacled caimans (Caiman crocodilus fuscus): Analysis of retinal ultrastructure. Exp Eye Res. 2018 Aug;173:160-178. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.05.006. Epub 2018 May 19. PMID: 29753728; PMCID: PMC9930524.

- ↑ McDougal DH, Gamlin PD. Autonomic control of the eye. Compr Physiol. 2015 Jan;5(1):439-73. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140014. PMID: 25589275; PMCID: PMC4919817.

- ↑ Yoo H, Mihaila DM. Neuroanatomy, Pupillary Light Reflexes and Pathway. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553169/

- ↑ Hultborn H, Mori K, Tsukahara N. The neuronal pathway subserving the pupillary light reflex. Brain Res. 1978 Dec 29;159(2):255-67. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90533-4. PMID: 215267.

- ↑ Javaudin F, Leclere B, Segard J, Le Bastard Q, Pes P, Penverne Y, Le Conte P, Jenvrin J, Hubert H, Escutnaire J, Batard E, Montassier E, Gr-RéAC. Prognostic performance of early absence of pupillary light reaction after recovery of out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2018 Jun;127:8-13. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.03.020. Epub 2018 Mar 12. PMID: 29545138.

- ↑ Sun W, May PJ. Central pupillary light reflex circuits in the cat: I. The olivary pretectal nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2014 Dec 15;522(18):3960-77. doi: 10.1002/cne.23602. Epub 2014 May 7. PMID: 24706328; PMCID: PMC4185307.

- ↑ Whiting RE, Yao G, Narfström K, Pearce JW, Coates JR, Dodam JR, Castaner LJ, Katz ML. Quantitative assessment of the canine pupillary light reflex. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 Aug 13;54(8):5432-40. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12012. PMID: 23847311; PMCID: PMC3743455.

- ↑ Dearworth JR Jr, Brenner JE, Blaum JF, Littlefield TE, Fink DA, Romano JM, Jones MS. Pupil constriction evoked in vitro by stimulation of the oculomotor nerve in the turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans). Vis Neurosci. 2009 May-Jun;26(3):309-18. doi: 10.1017/S0952523809090099. Epub 2009 Jun 15. PMID: 19523265.

- ↑ Ungurean G, Martinez-Gonzalez D, Massot B, Libourel PA, Rattenborg NC. Pupillary behavior during wakefulness, non-REM sleep, and REM sleep in birds is opposite that of mammals. Curr Biol. 2021 Dec 6;31(23):5370-5376.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.09.060. Epub 2021 Oct 19. PMID: 34670112.

- ↑ Warrington RE, Davies WIL, Hemmi JM, Hart NS, Potter IC, Collin SP, Hunt DM. Visual opsin expression and morphological characterization of retinal photoreceptors in the pouched lamprey (Geotria australis, Gray). J Comp Neurol. 2021 Jun;529(9):2265-2282. doi: 10.1002/cne.25092. Epub 2020 Dec 30. PMID: 33336375.

- ↑ Davies WL, Collin SP, Hunt DM. Adaptive gene loss reflects differences in the visual ecology of basal vertebrates. Mol Biol Evol. 2009 Aug;26(8):1803-9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp089. Epub 2009 Apr 27. PMID: 19398493.

- ↑ Davies WL, Cowing JA, Carvalho LS, Potter IC, Trezise AE, Hunt DM, Collin SP. Functional characterization, tuning, and regulation of visual pigment gene expression in an anadromous lamprey. FASEB J. 2007 Sep;21(11):2713-24. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-8057com. Epub 2007 Apr 26. PMID: 17463225.

- ↑ Stein JD, Khawaja AP, Weizer JS. Glaucoma in Adults—Screening, Diagnosis, and Management: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325(2):164–174. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.21899

- ↑ Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The Pathophysiology and Treatment of Glaucoma: A Review. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1901–1911. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3192

- ↑ Oikawa K, Teixeira LBC, Keikhosravi A, Eliceiri KW, McLellan GJ. Microstructure and resident cell-types of the feline optic nerve head resemble that of humans. Exp Eye Res. 2021 Jan;202:108315. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108315. Epub 2020 Oct 19. PMID: 33091431; PMCID: PMC7855208.

- ↑ Balaratnasingam C, Morgan WH, Johnstone V, Pandav SS, Cringle SJ, Yu DY. Histomorphometric measurements in human and dog optic nerve and an estimation of optic nerve pressure gradients in human. Exp Eye Res. 2009 Nov;89(5):618-28. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.06.002. Epub 2009 Jun 11. PMID: 19523943.

- ↑ Pizzirani S. Definition, Classification, and Pathophysiology of Canine Glaucoma. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2015 Nov;45(6):1127-57, v. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2015.06.002. PMID: 26456751.

- ↑ Chan G, Morgan WH, Yu DY, Balaratnasingam C. Quantitative analysis of astrocyte and axonal density relationships: Glia to neuron ratio in the optic nerve laminar regions. Exp Eye Res. 2020 Sep;198:108154. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108154. Epub 2020 Jul 24. PMID: 32712181.

- ↑ Heesy, C. P. (2007). Ecomorphology of orbit orientation and the adaptive significance of binocular vision in primates and other mammals. Brain Behavior and Evolution, 71(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/ 10.1159/000108621

- ↑ Read, J. C. A. (2021). Binocular vision and stereopsis across the animal kingdom. Annual Review of Vision Science, 7(1), 389–415. https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-vision-093019-113212

- ↑ Hughes, A. (1977). The topography of vision in mammals of contrasting life style: Comparative optics and retinal organisation. In F. Crescitelli, C. A. Dvorak, D. J. Eder, A. M. Granda, D. Hamasaki, K. Holmberg, A. Hughes, N. A. Locket, W. N. McFarland, D. B. Meyer, W. R. A. Muntz, F. W. Munz, E. C. Olson, R. W. Reyer, & F. Crescitelli (Eds.), The visual system in vertebrates (pp. 613–756). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.