Visual Acuity Assessment in Children

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Diagnostic Intervention

Description/Overview

Visual acuity is the assessment of the eye's ability to distinguish object details and shape, using the smallest identifiable object that can be seen at a specified distance (usually 20 ft. or 16 in.)[1] Visual acuity assessment in children remains a challenge for the ophthalmologist and must be correctly performed for the early diagnosis of refractive errors, amblyopia, and other ocular pathologies.[2] [3] However, lack of cooperation and comprehension in young children makes it a challenging task. Preschool children with lower visual acuity are usually unaware of their problem, unless the defect is bilateral and severe. Parents are also unable to suspect low vision in their children, especially in unilateral cases. As a result, children with anisometropia and small-angle strabismus usually have a delayed diagnosis.

Indications

The American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus recommend vision evaluation for newborns, and again at 6 months/12 months, 1-3 years of age, 3-5 years, and beyond 5 years.

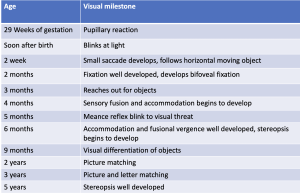

Normal visual acuity in various age groups is:

- At birth - 6/120 (20/400)

- 4 months-6/60 (20/200)

- 6 months-6/36 (20/120)

- 1 year-6/18 (20/60)

- 2 years- 6/6 (20/20)

Table 1 summarizes visual acuity milestones according to age.

Visual Acuity Assessment for Various Age Groups

Infants

Fixation

The fixation normally should be central, steady, and maintained (CSM).

Fixation behavior and fixation preference testing can be described using the CSM (Central, Steady, and Maintained) notation. Fixation during monocular viewing is described as central (foveal) or noncentral (eccentric), and steady (stable eye position) or non-steady (roving eye movements or nystagmus). Maintained refers to fixation that is held during binocular viewing after the opposite eye is uncovered during fixation preference testing.

Menace reflex

Menace reflex is a reflex blinking that occurs in response to a rapid moving object and visual threat. The reflex develops by 5 months of age.

Brückner reflex

The Brückner reflex test can help in the rapid screening of refractive errors. The test is performed in a dark room, and both eyes are simultaneously illuminated with the direct ophthalmoscope. The reflex is noted at a distance of 1 meter as well as at 3 meters. An inferior crescent suggests myopia, a superior crescent is seen in hyperopia. Resistance to occlusion of the eye with good vision also gives an estimation about the visual acuity discrepancies.

Optokinetic nystagmus

Optokinetic nystagmus is used to objectively determine the visual acuity of the child. A succession of black and white stripes is passed through the patient's visual field. The visual angle subtended by the narrowest width of the strip elicits an eye movement that measures the visual acuity. The visual acuity in the newborn child is at least 6/120 (20/400) by optokinetic nystagmus[4] and improves in the first few months of life. However, optokinetic nystagmus results can be false positive in patients with cortical blindness, as it has been suggested that subcortical mechanisms are involved in the generation of optokinetic nystagmus.[5] The test result can be false negative in infants with delayed development of the motor pathways and due to difficulties with attention.[6] [7]

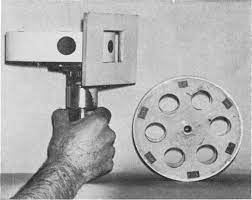

Catford drum test

The Catford drum test was introduced by Olive and Catford. It is an objective method to evaluate visual acuity by inducing optokinetic nystagmus. The motor-driven drum consists of separated black dots of various sizes on a white background projected through a screen measuring 4*6 cm. These dots can be rotated from left to right and then back from right to left in a rotating manner. The test is carried at a distance of 60 cm, and the child is instructed to watch the dot. The visual acuity is assessed by reducing the size of the dot until the smallest dot is found that can no longer induce optokinetic nystagmus. The end point is recorded and converted to the given Snellen equivalent. The drum has been calibrated between the visual acuity of 20/20 and 20/600 of Snellen acuity, based on the dot size at 60 cm.[8]

Preferential looking test

These tests are based on the principle that an infant's attention is more attracted by a patterned stimulus than a homogenous surface. Hence, if the infant is given a choice between a pattern and a plain surface, the infant shows a preference for the patterned surface.

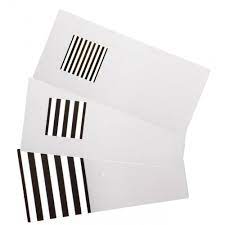

Teller acuity cards

The Teller acuity test was first described by Fantz [9] and was further developed by Dobson and Teller. During the test, the observer is hidden behind the screen. The screen has a homogeneous surface on one side and is alternated randomly with black and white stripes on the other side. The baby is faced toward the screen and the observer records the direction of head movement and eye movements in response to the patterned stimulus. The test is suitable for testing visual acuity in infants up to 4 months of age, as older infants are easily distracted. Visual acuities tested by this method range from 6/240 (20/800) in the newborn to 6/60 (20/200) at 3 months and 6/6 (20/20) at 36 months of age.[10] Later Teller acuity cards were introduced by McDonald and colleagues.[11] Teller acuity cards contain grating patterns of spatial frequencies. The cards are shown at a distance of 38 cm, and an observer watches an infant's eye and head movements in response to repeated presentation of these cards. In children with amblyopia, grating acuity is affected, because visual acuity can thus be underestimated. As a visual screening test, Teller cards have high false-positive results.

LEA Grating Acuity Test

LEA gratings are a preferential looking test used for visual acuity assessment of infants and children with disability. Grating levels printed on each handle are: 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 CPCM (cycles per centimeter of surface).

Visual evoked potential (VEP)

VEP is a measure of the cortical activity generated in response to the patterned stimulus, checkerboard, or square wave grating. In young children, flash or patterned VEP can also be used to record the visual acuity. Visual acuity of 6/6 (20/20) is achieved in VEP by 6-12 months of age.

1-2 Years

Worth Ivory ball test

Claud Worth in 1896 introduced the ivory ball test for the visual acuity assessment of children between 1-3 years of age. There is a set of 5 balls ranging from 0.5 inch to 2.5 inch. The child with both eyes opened is initially made familiar with the balls. One eye is then covered and each ball, beginning from the largest, is then thrown at a distance of 18 feet, and the child is asked to retrieve each of the balls.[12] Visual acuity is assessed by the size of the smallest ball that can be seen by the child.

Böck Candy test

In this test, the child is shown candy beads of different sizes at a distance of 40 cm. The child is then expected to pick up the candy beads. The smallest bead that the child can pick up gives the approximate estimation of the visual acuity.

2-3 years

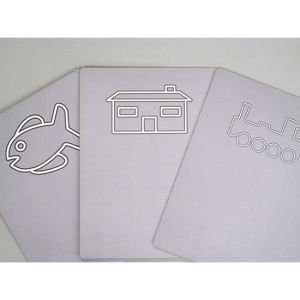

Cardiff Acuity Test

The Cardiff Acuity test is based on the principle of vanishing optotypes. It is a set of 6 cards with 6 easily recognizable shapes (house, fish, dog, duck, train) positioned either at the top or bottom half of a card. The cards are calibrated to give a visual acuity equivalent of 20/20 to 20/200 at 1 meter viewing distance. The child is comfortably seated, and the cards are presented at eye level at a distance of 1 meter. The examiner watches the eye movements toward the shape. If the child is looking at the shape, then the next card is presented. This procedure is continued until no definite fixation is observed. The test is performed at 1 meter distance, but it is altered to one-half meter if the child is unable to see the first card. The identification score and Snellen equivalent of each card are mentioned at the back of card.

Miniature toy test

The miniature toy test was previously used with children with disabilities and patients with cognitive disabilities. It used 2 sets of miniature objects. The examiner stands 10 feet away and picks up objects from one set. The patient is asked to pick up similar objects from a second set that is placed close to the patient. The objects chosen for the test are easily identifiable small toys, such as automobiles, planes, charts, knives, spoons etc. The same objects can be in 2-3 sizes, in order to check the grade of vision.

Coin test

Coins of different sizes are shown to the child, and the child is expected to pick up the coins easily visible.

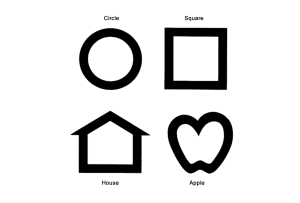

LEA symbols

LEA symbol tests were developed by Finnish ophthalmologist Dr Lea Hyvärinen. The oldest and most basic form of the LEA test is simply referred to as the "LEA Symbols Test". The LEA symbol test consists of 4 optotypes: an apple, a pentagon, a square, and a circle. These easily identifiable shapes help test the visual acuity of preschool children long before they become familiar with the letters and numbers used in other standard vision charts. Becker and colleagues found LEA symbols useful for visual acuity evaluation in early childhood.[13]

3-5 years

Allen picture test

The preschool vision test, or the Allen picture card test, consists of 7 black-and-white line drawings of birthday cake, a telephone, a horseman, a teddy bear, an automobile, a house, and a tree. These are line drawings on plastic (10 cm X10 cm) white cards. Child patients will be shown the cards at a closer distance so that they can recognize and identify them.

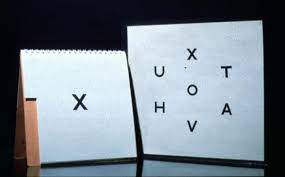

Sheridan letter test

This test uses letters that children can recognize and copy at an early age. The letters V T O H X A U are used and are shown to the child 1 at a time on flip card. The child is given a key card showing all the letters and then has to point to the letter that she or he sees. After explaining the procedure to the child, the test can be done at 6 meters or 3 meters. Sheridan Gardiner test is the most accurate of the illiterate vision test in children.

Lippman HOTV test

The Lippman HOTV test is similar to Sheridan letter test. It is a simpler version and consists of only 4 letters: HOTV.

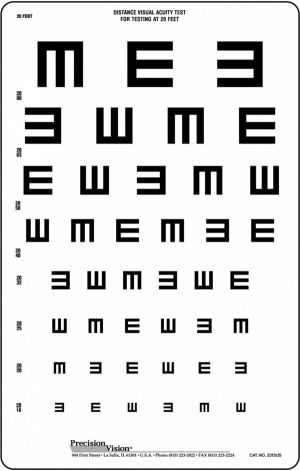

Tumbling E chart

The tumbling E chart is commonly used. The chart consists of an E with the limbs of the E pointing in various directions. The test can be used in 2 forms: either in the form of a chart (like the Snellen chart) or printed on an individual card.

Sjogren hand test

This test consists of pictures of hands with fingers pointing in various directions.

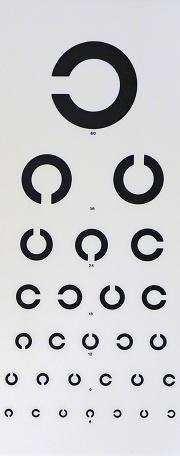

Landolt broken ring chart

The test is usually used for the visual acuity assessment in persons who cannot read. The broken ring is printed in various directions. The test is performed at a distance of 6 meters, and the child is asked to indicate the direction in which the ring is open.

Snellen chart

In older children who can recognize alphabet letters, the Snellen chart can be used.

Conclusion

Assessing the visual acuity of children requires patience and takes longer than it usually does with adults. The examiner should thus be well versed in all the possible methods for evaluation of visual acuity.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology, Dictionary of Eye Terminology, Eighth edition, San Francisco, CA, 2024.

- ↑ Riggs LA. Visual acuity. In: Graham CH ed. Vision and visual perception. New York: Wiley, 1965:321–349.

- ↑ Sheridan MD. Vision screening procedures for very young or handicapped children. In: Gardiner P, MacKeith R, Smith V, eds. Aspects of developmental and pediatric ophthalmology, Clinics in developmental medicine. London: Spastic International Medical Publications, 1969:39–47.

- ↑ GORMAN JJ, COGAN DG, GELLIS SS. An apparatus for grading the visual acuity of infants on the basis of opticokinetic nystagmus. Pediatrics. 1957 Jun;19(6):1088-92. PMID: 13441362.

- ↑ Van Hof-van Duin J, Mohn G. Optokinetic and spontaneous nystagmus in children with neurological disorders. Behav Brain Res. 1983 Oct;10(1):163-75. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(83)90162-6. PMID: 6639724.

- ↑ Enoch JM, Campos EC. Helping the aphakic neonate to see. Int Ophthalmol. 1985 Nov;8(4):237-48. doi: 10.1007/BF00137652. PMID: 4086171.

- ↑ Campos EC, Chiesi C. Critical analysis of visual function evaluating techniques in newborn babies. Int Ophthalmol. 1985 Apr;8(1):25-31. doi: 10.1007/BF00136458. PMID: 4019035.

- ↑ Catford GV, Oliver A. Development of visual acuity. Arch Dis Child. 1973 Jan;48(1):47-50. doi: 10.1136/adc.48.1.47. PMID: 4685594; PMCID: PMC1647792.

- ↑ Fantz RL. Pattern Vision in Newborn Infants. Science. 1963;140(3564):296-297.

- ↑ Mayer DL, Beiser AS, Warner AF, Pratt EM, Raye KN, Lang JM. Monocular acuity norms for the Teller Acuity Cards between ages one month and four years. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995 Mar;36(3):671-85. PMID: 7890497.

- ↑ McDonald M, Sebris SL, Mohn G, Teller DY, Dobson V. Monocular acuity in normal infants: the acuity card procedure. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1986 Feb;63(2):127-34. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198602000-00008. PMID: 3953755.

- ↑ Keeler R, Singh AD, Dua HS. Testing vision can be testing: Worth's ivory-ball test. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2012;96:633.

- ↑ Becker R, Hübsch S, Gräf MH, Kaufmann H. Examination of young children with Lea symbols. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002 May;86(5):513-6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.513. PMID: 11973243; PMCID: PMC1771129.