White-Eyed Blow Out Fracture

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

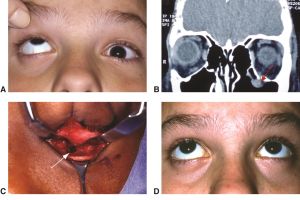

White-eyed blow out fracture (WEBOF) is a term for a single or multiple wall orbital fracture with intact orbital rim, with herniation and (typically) entrapment of periorbital soft tissues, restrictive strabismus and a clinically quiet 'white' eye'. There is usually no periorbital ecchymosis or subconjunctival hemorrhage. ICD codes include fracture codes (e.g. S02.40, S02.32) and restricted motility/diplopia codes.

Disease

A WEBOF is a type of blow out orbital fracture with orbital soft tissue herniation, which is often but not always associated with an entrapped extraocular muscle-inter muscular septum (EOM-IMS) complex which may result in restrictive strabismus and vasovagal phenomenon, especially in young children.

Etiology

As with other fractures, a WEBOF is due to trauma. The trauma can be a direct or indirect trauma to the eye and/or periorbital region and commonly occurs during sporting activities. White-eyed blow out fracture (WEBOF) is a term coined by Jordan and colleagues describing the paucity of external findings in setting of an orbital fracture. [1].

Risk Factors

Pediatric age group and male gender are more prone to WEBOFs, with average age of less than 10 years.

General Pathology

WEBOFs are usually caused by blunt force injury to the eye and/or orbital rim typically by a blunt object.

Pathophysiology

The hypothesized pathophysiology is from a force applied to the eye/orbital rim transmitting pressure to the orbit and an equatorial expansion of the intraorbital tissue. This expansion puts pressure on the orbital bones and can lead to a break in one of the weaker areas of bones, most commonly the orbital floor. Due to the less calcified, more flexible bone seen in the pediatric population, the bone can crack and open as if on a hinge. This trapdoor of bone can then snap back towards its original position when the pressure on the orbital tissue has decreased, capturing the orbital soft tissue in the process. This incarcerated tissue can be orbital fat with intermusculear septum and/or an extraocular muscle. This most commonly affects the orbital floor and inferior rectus muscle, with medial wall and rectus involvement less common. Most often these are isolated fractures, with or without concomitant intraocular injury(ies).

Primary Prevention

General safety guidelines to prevent trauma and activity specific sports eye wear are recommended.

Diagnosis

WEBOFs are generally diagnosed based on the history, high degree of suspicion and focused clinical examination. Radiographic studies such as plain X-ray or CT scan of the brain can overlook the small, non-displaced fracture. Cases are often misdiagnosed as these children may present with a history of blunt injury and vagal phenomenon upon attempted up-gaze (in setting of orbital floor involvement). They may be falsely suspected to have an intracranial injury and managed accordingly instead of appropriate and early intervention for the orbital fracture.

History

These fractures occur in a younger age demographic in the setting of recent trauma, although trauma is not always known in young children. There may be a delay in presentation due to the lack of significant external findings (e.g. bruising) and even possibly a reportedly "normal" CT scan of the brain , which may miss a subtle orbital floor fracture or soft tissue herniation.

Physical Examination

On examination, patients often have an unremarkable external examination with a paucity of periorbital bruising and/or swelling as the name "white eyed" implies. Patients may preferentially avoid eye opening or looking up (floor fracture) to avoid nausea or pain. With dedicated ocular motility examination there is marked limitation of gaze (up gaze for inferior rectus, lateral gaze for medial rectus) . This may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting, due to the oculocardiac reflex, and/or pain with motility. There may or may not be decreased sensation due to infraorbital nerve injury. Enophthalmos is uncommon or not that obvious especially in an uncooperative child while the rest of the ocular examination, including full dilated examination, is unremarkable.

Signs

The external signs can be absent or quite subtle, as the name suggests. The patient often has her/his eyes closed due to induced nausea and diplopia from restriction in motility, generally vertically. Additionally, with attempted ductions the patient may vomit and/or become bradycardic. Rarely asystole or cardiac arrythmia may also occur.

Symptoms

The child may have double vision on opening or moving the eyes, pain with eye movement, diplopia and nausea. Due to natural eye closure tendency, they may not complain of these symptoms.

Clinical Diagnosis

A WEBOF is generally a clinical diagnosis confirmed on dedicated orbital imaging with CT scan. A pediatric or young adult patient with restrictive strabismus and pain after trauma and minimal external signs is generally suspected of having a WEBOF even without further testing or radiologic imaging. In older more cooperative patients forced ductions may confirm the clinical diagnosis, but is generally not needed or tolerated.

Diagnostic procedures

A CT scan of the orbits and sinuses is generally performed in addition to a full eye exam, despite WEBOF being a clinical diagnosis. The CT will generally demonstrate a linear orbital floor fracture parallel to the canal with minimal or no displacement, which may be read as normal. The incarcerated soft tissue, fat +/- extraocular muscle (EOM), is seen in the adjacent sinus and may be reported as a sinus polyp. It is imperative to read the fine cuts of CT scans on coronal and sagittal cuts (orbital floor) and coronal and axial cuts (medial wall). Additionally the incarcerated EOM within the orbit may be distorted or have areas where the muscle can not be identified, the "missing muscle sign".

Differential diagnosis

As with any trauma, a full exam should be performed to rule-out other or additional diagnoses as often these patients have had a history of blunt head/facial trauma and warrant neurological examination and observation. Laceration or contusion of EOM, or rarely paresis could cause some of these signs. Patients are often initially misdiagnosed with a concussion prior to the WEBOF being identified.

Management

WEBOF should ideally have any entrapped tissue(s) surgically released within 24-48 hours of injury. In general, the younger the child, the earlier the exploration and release of the orbital soft tissues. Rarely, a forced duction test may be therapeutic as well, although it may be quite uncomfortable and cause muscle damage.

Medical therapy

Medical therapy should be used to control nausea and vomiting and cardiac monitoring and preparation for general anesthesia prior to surgical repair.

Surgery

Surgery is performed under general anesthesia with laryngeal mask anaesthesia (LMA) or endotracheal intubation. Once the patient is asleep and draped, leaving both eyes in the surgical field, forced ductions should be performed at baseline which may be both diagnostic and occasionally therapeutic as well.

Local anesthetic infiltration with epinephrine of the fornices and lateral canthal region may be performed prior to incisions avoiding infraorbital injection and thus globe injury or pupillary dilatation.

Typically an transconjunctival approach - inferior with or without lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis for floor fractures and medial via a transcaruncular approach for medial wall fractures. The cornea should be protected but with access for pupillary monitoring through out the procedure.

Inferior wall blow out fracture: A high (sub tarsal) or low (inferior forniceal) conjunctival incision is made with dissection towards the inferior orbital rim. The periosteum is incised (blade or sharp monopolar cautery) just anterior to the arcus marginalis and elevated over the anterior wall of maxilla and along the floor until anterior end of fracture site is identified. Depending on the size of the defect the orbital contents may be elevated with a hand-over-hand technique. If difficult and the bony defect is small, aggressive elevation of soft tissue should not be performed. Instead the bony defect may be enlarged by manoeuvring the trapdoor towards the maxillary sinus with a 'push and sweep technique' releasing the orbital soft tissue with atraumatic return of orbtial contents. Care should be taken to avoid rupturing the herniated muscle and damaging the infraorbital neuromuscular bundle. The entire orbital defect should be directly visualised identifying the anterior, medial, lateral and posterior edges with complete release or orbital contents an normal forced duction tests. Aggressive intrazonal tissue manipulation should be avoided to minimise damage to the extra ocular muscle and ciliary ganglion.

If the fractured bone realigns with little or no residual defect, an orbital implant may not be necessary. More often for small-to-medium sized defects either a bioresorbable or permanent alloplastic implant may be placed over the defect to prevent reherniation of orbital soft tissue contents prior to repeating forced suction test before wound closure which may be performed in layers - periosteum and conjunctiva, and not the orbital septum. Implants used in pediatric orbital fractures include bioresorbable (polylactides (Rapidsorb(R), polycaprolactones (Osteopore(R))).[2].

Surgical follow-up

Postoperatively, the patient’s vision and pupillary reactivity are checked once the patient is awake to assure that there is no evidence of orbital compartment syndrome or optic neuropathy. Any pre-operative nausea, vomiting, and pain with ductions should resolve almost immediately after surgery. There can be a delay in return of full rectus muscle function, depending on degree and duration of muscle injury.

Complications

See orbital fracture for complications. Specifically, for pediatric orbital fracture reconstructions, exaggeration or persistence of preoperative strabismus and symptomatic diplopia may be present and patients/parents cautioned regarding the same. Visual loss is rare but may occur especially with large fractures, late repairs and aggressive dissection/instrumentation and implant misplacement.

Prognosis

In general, the earlier and less traumatic the procedure with complete reduction of orbital contents, the better the prognosis for complete recovery. However, diplopia may linger for weeks and may paradoxically worsen in the immediate postoperative phase. This is an important point to discuss with the patient and parents before surgery. It is not uncommon for the freed muscle to remain paretic for days to weeks, resulting in a marked hypertropia of the eye in the case of inferior wall WEBOF. As the inferior rectus heals and recovers function, the strabismus improves and hopefully resolves completely. On occasion, a small residual diplopia may persist in extreme up- or downgaze. If significant strabismus and diplopia is present several weeks after repair and an adequate reduction was performed intraoperatively, intramuscular fibrosis is likely present. Rarely, incomplete reduction of orbital contents may be present and may justify early exploration and reconstruction with associated risks. Very young patients (<4 years old) with postoperative diplopia or strabismus should be followed for the development of amblyopia. Otherwise, serial strabismus measurements should be performed to document improvement or stability. Strabismus surgery, when necessary, should be delayed for at least six months following initial repair.

References

- ↑ Jordan DR, Allen LH, White J, Harvey J, Pashby R, Esmaeli B. Intervention within days for some orbital floor fractures: the white-eyed blowout. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;14:379-90

- ↑ Lane KA, Bilyk JR, Taub D, Pribitkin EA. "Sutureless" repair of orbital floor and rim fractures. Ophthalmology 2009;116:135-8 e2.