Acute Retinal Pigment Epitheliitis (Krill Disease)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Acute retinal pigment epitheliitis (ARPE), also known as Krills disease, is a rare, self-limiting inflammatory disease of the retina, first described by Alex E. Krill and August F. Deutman in 1972.[1][2][3][4] The original description characterized the retinal lesions as clusters of small, round, dark-gray spots surrounded by circular, whitish, depigmented zones in the macula.[4] ARPE typically has an acute onset and resolves relatively quickly within 6 to 12 weeks, often with complete or near-complete recovery of vision. The condition most commonly affects healthy adults aged 20 to 50 years. Its overall incidence is unknown, and males and females appear to be equally affected.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of ARPE remains unknown. Similar to other white dot syndromes, flu-like symptoms have occasionally been reported prior to disease onset, suggesting a potential viral contribution to its pathogenesis.[5] However, a case series of 18 patients found that only 17% experienced prodromal influenza-like symptoms.[1]

While earlier studies suggested that the primary site of inflammation was the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), recent studies using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) indicate that inflammation is primarily localized to the interdigitation zone—the interface between the photoreceptors and the RPE—rather than the RPE itself.[6]

Diagnosis

History

Patients typically present with acute, painless vision loss or a central scotoma.[1][4][5] The condition usually affects only one eye, although bilateral involvement can occasionally occur. Prodromal influenza-like symptoms may be reported 1–2 weeks prior to symptom onset.

Physical Examination

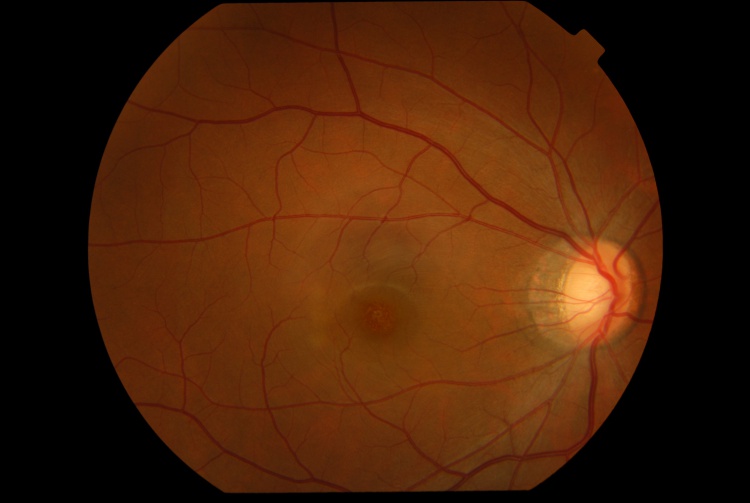

Presenting visual acuity is typically around 20/40, ranging from 20/30 to 20/100, and Amsler grid testing often reveals a central scotoma.[1][6] The anterior segment examination is typically unremarkable, and signs of intraocular inflammation are absent. Fundus examination characteristically demonstrates fine pigment stippling in the macula, surrounded by a hypopigmented halo (Figures 1 and 2).[4][6][7] A few white dots may also be observed in the extrafoveal macular region.[6][8]

Diagnostic Procedures

The diagnosis of ARPE is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic presentation and the distinctive fundus features. OCT helps to support the diagnosis. Multimodal imaging can a valuable tool to support the diagnosis and exclude other conditions.

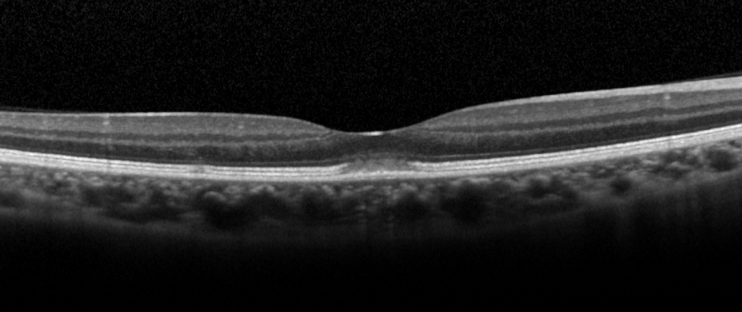

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT is the investigation of choice for diagnosis and follow-up of patients. The characteristic OCT feature is a dome-shaped hyperreflective lesion at the photoreceptor outer segment layer disrupting the ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone (Figure 3).[1][6] The outer nuclear layer may be involved by the hyperreflective lesion.[2][6] In the early phase of the disease (within 2 days of symptoms onset), upward displacement of the external limiting membrane and mild transient thickening of the RPE/Bruch’s complex can be seen.[6] En-face OCT may show a cockade-like lesion with a hypo-reflective centre and hyper-reflective border at the level of ellipsoid zone, and a hyper-reflective punctate lesion at the level of outer nuclear layer in the fovea.[5]

Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF): FAF may show slight increased autofluorescence in the foveal center and in the areas corresponding to the hypopigmented white dots.[6][8] FAF may be unremarkable in some patients.[5]

Fluorescein Angiography (FA): FA shows hyperfluorescence at the fovea due to a transmission window defect in 83% of cases.[1][9][10] Leakage of fluorescein dye is absent.[1][11] FA may be unremarkable in some patients.[1]

Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICG): In the early phase, ICG is typically unremarkable.[1] In the mid-to-late phase, ICG may show a small patch of hyperfluorescence in the fovea (1 in 6 cases) or a halo-like hyperfluorescent lesion (4 in 6 cases).[1] ICG, like FA, may also be unremarkable in some patients.[1][6]

Visual Field Test shows decreased threshold sensitivity in the central region.[12]

Multifocal Electroretinogram shows depression of central amplitudes.[13]

Electro-oculogram may show a decreased Arden ratio.[4][13]

Differential Diagnosis

Multiple Evanescent White Dot Syndrome: MEWDS is an inflammatory retinal disease in the family of white dot syndromes. Similar to ARPE, MEWDS typically affects young adults and is self-limiting.[14] The pathognomonic orange foveal granularity in MEWDS may resemble the foveal pigment stippling in ARPE. However, MEWDS typically shows a more extensive retinal involvement where multiple whitish dots at the level of outer retina can be seen extending from posterior pole to equator.[14] FA and ICG are useful to differentiate MEWDS from ARPE. In MEWDS, FA shows a punctate hyperfluorescence in a wreath-like configuration, and ICG shows multiple hypofluorescent dots that out-number the visible lesions seen ophthalmologically and on FA.[14]

Acute Macular Neuroretinopathy: Similar to ARPE, patients with AMN present with sudden onset of central or paracentral scotoma.[15] AMNR appears as reddish-brown, wedge-shaped lesions in the paracentral region in a tear-drop configuration pointing towards the fovea.[15] The pathogenesis was postulated to be due to ischemia of the deep retinal capillary plexus.[15] Therefore, OCT of AMNR shows hyper-reflective plaques at the border of outer plexiform layer and outer nuclear layers,[15] whereas in ARPE the hyper-reflective lesion was mainly located at the photoreceptor outer segment layer.[6]

Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy: Similar to ARPE, AIM typically affects young adults and presents as acute unilateral visual loss.[16] OCT is useful to differentiate AIM from ARPE. OCT of AIM shows swelling of outer retina with presence of hyper-reflective exudation and hypo-reflective fluid in the subretinal space,[17] whereas OCT of ARPE shows a dome-shaped hyper-reflective lesion at the photoreceptor outer segment layer disrupting the ellipsoid zone and interdigitation zone.

Solar Retinopathy appears as yellowish dot in the fovea.[18] OCT may show disruption of the outer retinal layers.[18] Diagnosis depends on a history of direct sun-gazing or eclipse viewing and bilateral foveal involvement.

Management

General Treatment

Treatment is generally unnecessary in most cases due to the self-limiting nature of the disease.[1][19] Complete recovery of visual acuity and spontaneous resolution of the lesion are typically observed within weeks without intervention. The use of oral corticosteroids has not been shown to shorten the course of recovery, and in a case series of four patients with ARPE, the three patients who received oral corticosteroids experienced slower visual recovery compared with the untreated patient.[6]

During recovery, OCT shows a typical pattern where the inflammatory lesion reduces in height and the retinal layers restore in order from inner to outer layers (Figure 4).[6] The recovery involves a sequence of: (1) decrease in height of OCT hyper-reflective lesion and the displaced external limiting membrane returned to its normal position with irregularity, (2) complete disappearance of the hyper-reflective lesion, (3) restoration of external limiting membrane, (4) restoration of ellipsoid zone, and (5) restoration of interdigitation zone. Occasionally, a persistent defect in the ellipsoid zone may remain, which can be associated with incomplete visual recovery.[20]

Prognosis

The prognosis of ARPE is excellent. Complete recovery of visual acuity to 20/20 occurs in approximately 89% of patients within 2 months.[1] However, cases of incomplete visual recovery persisting for more than one year have been reported. Poor prognostic factors include a baseline visual acuity worse than 20/70 and extensive retinal involvement affecting the outer nuclear layer.[1] Recurrences are exceedingly rare. [21]

Additional Resources

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Acute Retinal Pigment Epitheliitis. Focal Points - Excerpt. https://www.aao.org/education/focalpoints Accessed 25 September 2024.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Cho HJ, Han SY, Cho SW, Lee DW, Lee TG, Kim CG, Kim JW. Acute retinal pigment epitheliitis: spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings in 18 cases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55(5):3314-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Baillif S, Wolff B, Paoli V, Gastaud P, Mauget-Faysse M. Retinal fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings in acute retinal pigment epitheliitis. Retina 2011;31(6):1156-63.

- ↑ Fouad YA, Cicinelli MV, Marchese A, Casalino G, Jampol LM. Revisiting acute retinal pigment epitheliitis (Krill disease). Surv Ophthalmol. 2024 Nov-Dec;69(6):916-923. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2024.07.003.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Krill AE, Deutman AF. Acute retinal pigment epitheliitus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;74:193-205.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 De Bats F, Wolff B, Mauget-Faysse M, Scemama C, Kodjikian L. B-scan and "en-face" spectral-domain optical coherence tomography imaging for the diagnosis and followup of acute retinal pigment epitheliitis. Case Rep Med 2013;2013:260237.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 Iu LPL, Lee R, Fan MCY, Lam WC, Chang RT, Wong IYH. Serial Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Acute Retinal Pigment Epitheliitis and the Correlation to Visual Acuity. Ophthalmology 2017;124(6):903-9.

- ↑ Merkoudis N, Granstam E. Acute retinal pigment epitheliitis: optical coherence tomography findings at onset and follow-up. Acta Ophthalmol 2013;91(1):e84-5.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Aydogan T, Guney E, Akcay BI, Bozkurt TK, Unlu C, Ergin A. Acute retinal pigment epitheliitis: spectral domain optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography, and autofluorescence findings. Case Rep Med 2015;2015:149497.

- ↑ Hall EF, Ahmad B, Schachat AP. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings in acute retinal pigment epitheliitis. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2012;6(3):309-12.

- ↑ Hsu J, Fineman MS, Kaiser RS. Optical coherence tomography findings in acute retinal pigment epitheliitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143(1):163-5.

- ↑ Moroz I, Alhalel A. Resolution of retinal pigment epitheliitis-optical coherence tomography findings. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2008;2(2):101-2

- ↑ Kim JW, Jang SY, Park TK, Ohn YH. Short-term clinical observation of acute retinal pigment epitheliitis using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Korean J Ophthalmol 2011;25(3):222-4.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Gundogan FC, Diner O, Tas A, Ilhan A, Yolcu U. Macular function and morphology in acute retinal pigment epithelitis. Indian J Ophthalmol 2014;62:1156-8.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 dell'Omo R, Pavesio CE. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS). Int Ophthalmol Clin 2012;52(4):221-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Bhavsar KV, Lin S, Rahimy E, Joseph A, Freund KB, Sarraf D, Cunningham ET, Jr. Acute macular neuroretinopathy: A comprehensive review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 2016;61(5):538-65.

- ↑ Hoang QV, Strauss DS, Pappas A, Freund KB. Imaging in the diagnosis and management of acute idiopathic maculopathy. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2012;52(4):263-8.

- ↑ Srour M, Querques G, Rostaqui O, Souied EH. Early spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings in unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Retina 2013;33(10):2182-4.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Wu CY, Jansen ME, Andrade J, Chui TYP, Do AT, Rosen RB, Deobhakta A. Acute Solar Retinopathy Imaged With Adaptive Optics, Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography, and En Face Optical Coherence Tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136(1):82-5.

- ↑ Fouad YA, Cicinelli MV, Marchese A, Casalino G, Jampol LM. Revisiting acute retinal pigment epitheliitis (Krill disease). Surv Ophthalmol. 2024 Nov-Dec;69(6):916-923.

- ↑ Cho HJ, Lee DW, Kim CG, Kim JW. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in acute retinal pigment epitheliitis. Can J Ophthalmol 2011;46(6):498-500.

- ↑ Roy R, Saurabh K, Thomas NR. MULTICOLOR IMAGING IN A CASE OF ACUTE RETINAL PIGMENT EPITHELIITIS. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021 Jan 1;15(1):45-48. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000726. PMID: 29474220.