Biometry for Intra-Ocular Lens (IOL) Power Calculation

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Background

Biometry is the method of applying mathematics to biology and was a term originally used by Whewell in the 1800s for calculating life expectancy. The refractive power of the eye primarily depends upon the cornea, the lens, the ocular media, and the axial length of the eye. To achieve the desired postoperative refraction after cataract surgery, biometry is used to calculate the required power of the intraocular lens (IOL) implant using the corneal refractive power, media type, and axial length. [1]

History

In 1949, Harold Ridley implanted the first IOL but discovered after surgery that his patient had a refractive surprise of nearly 20 D. To address this, Fyodorov and co-workers subsequently used vergence formulas to estimate the optical power of an IOL in 1967.[2] In the 1970s, after accurate “A” scans became available, several studies were conducted with the goal of establishing various theoretical vergence formulas. Then, in the early 1980s, attempts were made to develop ideal emmetropia (IDEM) lenses—so named for their similar pre- and post-refraction capabilities—and standard lenses (after Gernet and Zorkendorfer showed that the average refractive power of the natural lens is +23.70 D). The theoretical formulas that were derived around the same time have since undergone various alterations to increase their predictive accuracy.[3]

Definitions

Emmetropia

Emmetropia refers to a state of no refractive error, the ideal postoperative outcome, for which maximum biometry is carried out. However, some patients may benefit from either a hypermetropic or myopic postoperative status because of their occupational or social needs (e.g., low-vision aids). Sometimes the fellow eye's refractive state has to be considered, as in cases of monovision or anisometropia that require a between-eyes refractive difference <3 D.

Keratometry (K): Refractive State of the Cornea

Keratometry is a measurement of corneal power and is based on the steepness of the cornea. Cornel power is estimated using the corneal curvature, which is based on the assumption that the cornea is a perfectly spherical, convex, optical mirror with a fixed anterior-to-posterior corneal curvature ratio and par-axial optics that lead to a virtual image of the target. Most keratometers do not provide enough information to accurately calculate corneal curvature. Moreover, the power of the back of the cornea must also be estimated (though newer posterior-imaging techniques can calculate this measure). Computerized video keratography, which is gaining standardization, provides more accurate results overall.[4] [5]

Axial Length (AL)

Axial length is defined as the distance from the anterior corneal surface to the retinal pigment epithelium and can be obtained using optical or ultrasound (contact or immersion) methods. Measurements taken via optical methods (e.g., IOL Master) have the benefit of being non-contact, and they typically offer improved accuracy; however, optical measurements can lose accuracy or be difficult to obtain in patients with dense cataracts. Contact ultrasound measurements, once the gold standard, are likely to have more subjective errors due to corneal compression. Immersion ultrasound avoids the corneal compression issue, but it offers less control over alignment, thus can give rise to varied results. A combination of techniques can help minimize errors.[4][5]

A-constant

The A-constant depends on several factors:

- IOL: type, material, position

- Surgeon: technique of incision, placement of incision

- K and AL measurement adjustments

- Adjustment for the manner of carrying out biometry.

Once fixed for a particular surgeon, IOL, and scanning device, the A-constant is applied as a constant to the appropriate IOL power formula. The A-constant varies approximately 1:1 with the IOL power.[5][6]

Gain

Defined as the electronic amplification factor of the sound waves received by the transducer, gain is measured in decibels (dB). The normal setting is around 70%–75%, but this may be increased in situations where high echoes are inadequate (e.g., hard cataracts, dense ocular opacities, high myopia). Gain is decreased when artifacts are seen near the retinal spikes (e.g., silicone-filled eyes, eyes with pseudophakia).[7]

Mathematics and Measurements

IOL Formula Origins

Formulas for calculating IOL power have been evolving since their inception and can be classified on the basis of their derivation (theoretical, regression analysis, or combination) or their generation of evolution.[5][6][7] Theoretical formulas are determined by applying geometrical optics to the schematic and reduced eyes using various constants. Regression analysis using actual postoperative results of implant power as a function of the variables of corneal power and axial length were later derived. The original SRK formula (developed by Sanders, Retzlaff and Kraff), though it has since been replaced with newer formulas, is still useful for understanding the relationship between the variables and A-constant to the IOL Power (P):

P = A – 0.9 K – 2.5 AL

P = Power of the IOL (D)

A = A-constant

K = Average keratometry value (D)

AL= Axial length (mm)

This basic SRK formula should only be used to calculate IOL power manually when other tools are not available.

Modern Formulas: Underlying Principles & Parameters

Most of the modern formulas are based on Fyodorov's theoretical equation:

P = (1336/[AL−ELP]) – (1336/[1336/{1000/([1000/DPostRx] − V) + K} − ELP])

K = Net corneal power

AL = Axial length

P = Power of the IOL

ELP = Effective lens position

DPostRx = Desired postoperative refraction

V = Vertex distance

The only variable in this equation that cannot be measured preoperatively is ELP; most subsequent formulas (e.g., Holladay, Hoffer Q, SRK/T, Haigis) attempt to more accurately calculate ELP.[8]

Effective Lens Position (ELP)

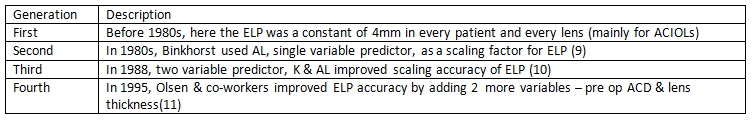

Effective lens position was the term used to denote the position of the lens in the eye—specifically the distance that the principal plane of the IOL will sit behind the cornea. The older variable, anterior chamber depth (ACD), was found to be anatomically inaccurate for an “in the bag” implanted IOL. Table 1 summarizes the early evolution of ELP in IOL power formulas. [9]

Newer formulas with modifications to improve postoperative refraction accuracy have continued to develop, but improvements in accuracy are also due to increased surgical proficiency and cataract techniques over the years. Some newer formula examples include the Holladay 2, which uses patient age and preoperative refraction as additional variables, and Haigis, which replaces K with preoperative ACD. The Barrett formula also incorporates ACD into its calculations.

Using Gaussian reduction equations, the IOL power formula can also be expressed in accordance with the refractive index (illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1):[10]

P = [nv/(AL − C)] − [K/(l − K × C/nA )]

P = Power of the target IOL (D)

K = Average dioptric power of the central cornea (D)

AL = Visual axial length (mm)

C = ELP (MM), the distance from the anterior corneal surface to the principal plane of the IOL

nv = index of refraction of the vitreous

nA = index of refraction of the aqueous

The ELP in the original formulas was a constant, as the lenses used were mostly placed in the anterior chamber. Hence, ELP was incorporated into the “A” constant in later regression analyses (like SRK). The newer formulas today generally use only one constant, incorporated as either A-constant or Surgeon Factor (SF). The original A-constant from the 1980s was so widely used that every lens was designed with a specific A-constant by the manufacturer. Even though regression analysis is not recommended today, the A-constant remains, due to its benefits in emergency usage and manual derivation for confirmation.[11]

Corneal Power (K)

Corneal power is considered to be the second most important factor for IOL power determination. Changes in K alter the IOL power in a ratio of nearly 1:1. Corneal power can be measured either by keratometry or topography, but neither measures the actual corneal power directly. The mathematical principle behind the keratometry method is that the central cornea is assumed to be a perfect sphere and acts as a spherical convex mirror. Further, the posterior corneal curvature is assumed to be 1.2 mm steeper than the anterior; this is especially altered after refractive surgeries, which results in increased observed refractive errors. The radius of curvature is determined from the size of the reflected image:

r = 2u × (image size/object size)

r = Radius of curvature (mm)

u = Distance of object from principle plane (mm)

It is then converted to power:

D = (n2 – n1) / r

D = Dioptric power

r = Radius of curvature

n = Refractive index of (medium 1 and 2)

Topographical methods use the Scheimpflug principle (via the Pentacam or the Galilei [double Scheimpflug]) to measure the anterior and posterior radii of corneal curvature along with the corneal thickness, which are then used to derive corneal power. In a normal phakic eye, the average anterior corneal radius of curvature is 7.5 mm, which corresponds to 44.44 D using a keratometric refractive index of 1.3333 (equivalent to 4/3), which was found to be more accurate than the 1.3375 refractive index used in older formulas. The posterior corneal radius of curvature averages 1.2 mm less than the anterior surface radius.[12]

Axial Length (AL)

Axial length is perhaps the most important parameter in most modern formulas and is an average of 24 mm in a normal, adult phakic eye.[13] Axial length changes the IOL power by nearly 2.5 to 3 times, more so in short eyes than in longer ones. Axial length can be measured using ultrasonography (contact or immersion) or optical methods (e.g., IOL Master, Lenstar). Ultrasonography uses mechanical waves to calculate the time needed for a pulse to travel from the cornea to the retina. Sound travels with different speeds depending on the media, faster in the lens and cornea (1641 m/s) and slower in the aqueous and vitreous (1532 m/s). The average velocity in a normal phakic eye is 1555 m/s. This time is then use to calculate distance (i.e., axial length):

Distance (m) = time (s) × velocity (m/s)

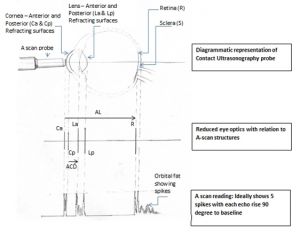

Ultrasonography methods can be applanation- or immersion-based, the former being less accurate due to indentation but the latter offering less control. Ultrasound data is displayed as an A–scan (amplitude modification), a one-dimensional display in which echoes are represented as vertical spikes from a baseline.

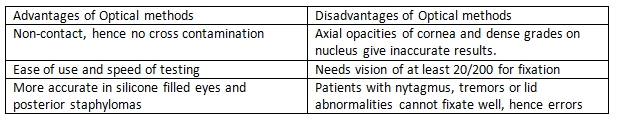

Optical methods for measuring AL use a partial coherence laser. Similar to ultrasonography, optical methods measure the time needed for infrared light to travel from the cornea to the retina. However, optical methods use the interferometry principle to avoid the problem of very high light speed measurements. In addition, as optical measuring of AL is a non-contact procedure, there are no indentation errors. Two main instruments are available for optical methods: IOL Master (Zeiss) and Lenstar (Haag-Streit). Advantages and disadvantages of optical methods are summarized Table 2.[14][15]

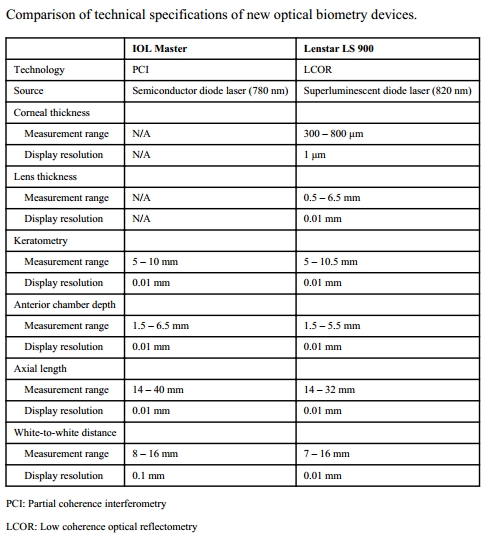

About 8%–17% of eyes cannot be measured using the optical methods, hence immersion continues to have a role. [15] A comparison between the newer devices for optical methods is shown in Table 3.[4] No statistically significant differences in the measurement of AL by IOL Master, Lenstar, and immersion ultrasonography have been reported.[16]

Special Circumstances

Aphakia

Aphakia affects the speed of sound travel (~1532 m/s in aphakic eyes), and the two lens spikes in the A-scan for aphakic eyes are absent, replaced by a single spike from the anterior vitreous face and posterior capsule. For these eyes, the immersion method is preferred over the contact method; newer devices have specially programmed modes for aphakia.[7] Most of the other IOL power calculation values remain similar, except ACD and the measured K reading. Since the manufacturer’s ACD is for in-the-bag placement (unless special lenses are utilized), the formula ACD value should be reduced by 0.25 mm for instances of sulcus placement. For posterior iris fixation, a further ACD reduction by 0.25 mm is needed.[17] Similarly, the measured K reading must be converted to the net K reading using a refractive index of 1.3333 (or 4/3).[18]

Pseudophakia

Pseudophakia is an important consideration for IOL exchange or for comparison while performing biometry on the fellow eye. Eyes with an IOL have an extremely high spike at the lens followed by an artificial chain of reduplication echoes, which can be confused with retinal spikes. These artifacts are avoided by reducing the gain, decreasing the artificial spikes and making true retinal ones more prominent. With pseudophakia, the speed of sound travel depends upon the type of IOL and its parameters. Newer devices have prefilled data specific to the type of implant.[7]

Optical biometry is preferred for pseudophakia, as it offers more accurate correction of the AL through the use of a correction factor, which varies based on the lens type and thickness.[19] For example, the conversion factor for polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) lenses is +0.45, for silicone lenses −0.56 or −0.41 (depending on the style and manufacturer), and for acrylic lenses +0.30. Lens thickness (t) must be obtained from the manufacturer.[20] For these eyes:

TAL = AAL 1532 + (CF × t)

TAL = true axial length

AAL 1532 = apparent axial length at 1532 m/s

CF = correction factor

t = lens thickness

Pediatric Patients

In pediatric patients, especially those who are very young, shorter AL leads to increased errors in AL measurement, which compound the final IOL power errors. Axial length and K value must both be measured under general anesthesia. Additionally, the selected IOL power should allow for good vision throughout childhood to prevent amblyopia and ideally provide emmetropia as an adult.

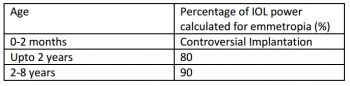

While older children are advised to undergo IOL implantation, some controversy exists surrounding whether children less than 2 years of age should receive an IOL. The greatest concern for implantation at very early age is the prevention of amblyopia. When implanting in young eyes, consider that development of the eye necessitates initial under-correction to avoid later myopic shift. The growth of the anterior segment is usually completed at around two years of age, thus the target IOL power is about 80% of the calculated amount of power (Table 4). These corrections are intended for use with newer generation formulas, such as SRK/T.[21] [22] [23]

A piggyback IOL approach, in which one implant is permanently placed in the bag and the other is temporarily placed in the ciliary sulcus, has been suggested by Dr. M. Edward to address these concerns. The temporary IOL is removed when the patient reaches adulthood.[24]

After Posterior Segment Surgery

The major concern when considering IOL implantation in silicone-filled eyes after vitrectomy is that the velocity of sound in silicone is slower than in vitreous, which must be corrected for in order to accurately measure AL. It is important to know which silicone has been used, as the two most common types of silicone have different tissue velocities (1050 m/s and 980 m/s), which could induce small errors in AL measurement. Newer machines offer settings to address this concern.

Silicone in the eye also acts as a negative lens when a biconvex IOL is implanted; hence, the IOL power must be adjusted by 3–5 D. Measurement adjustments to improve accuracy can also be achieved by calculating each segment's ratio and then obtaining the IOL value by appropriate alteration.[25] In silicone-filled eyes, measurement of AL using the optical method is much more accurate than other methods.[26]

After Refractive Surgery

Corneal refractive surgeries alter the basic assumptions upon which the biometry for IOL calculations are based, namely the perfectly spherical nature of cornea. These refractive surgeries mainly affect the central cornea, though the posterior corneal curvature may also be altered. Three main types of errors are possible:

- Instrument errors—Keratometers measure a 3.2-mm zone diameter, but they are unable to measure the central zone of effective corneal power. The flatter the cornea, the greater the measurement zone, and the greater the error.

- Refractive index (RI)—Refractive index is based on the ratio between the anterior and posterior corneal curvatures. Most instruments only measure the anterior curvature while making assumptions about the posterior curvature to derive the RI (and K). The relationship between the curvatures is altered in photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK), and radial keratotomy. This can lead to overestimations of the corneal power by 1D for every 7D of correction of refractive error.

- Formula error—Most modern IOL formulas (e.g., SRK/T, Holladay) use axial length and keratometry to predict effective lens position, but they don't account for how refractive surgery alters corneal shape without proportionally changing other anterior chamber dimensions. This leads to inaccurate effective lens position predictions and IOL power calculation errors.[27]

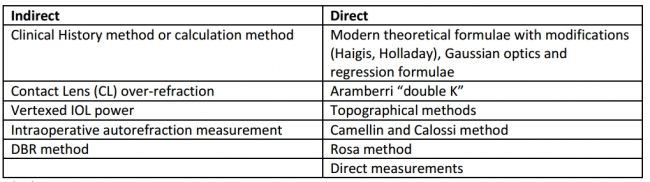

Methods of Measuring IOL Power: Indirect vs Direct

"Indirect" and "direct" methods of measuring corneal power after refractive surgery exist: direct involves actual measurements whereas indirect makes assumptions based on historical data or theoretical analysis and involves measurements outside of post–refractive surgery corneal power readings (Table 5).[26]

Indirect Methods

- Clinical History or Calculation method—The most accurate method, this formula incorporates preoperative K, preoperative refraction, and stabilized postoperative refraction to calculate corneal power; preoperative values are precise up to ± 0.25 mm.[28] Stabilized refraction must be measured before changes in refraction occur due to cataractous alterations.

K postReSx = K preReSx – (preoperative SE − postoperative SE)

- Contact Lens (CL) Over-Refraction—This method calculates post–refractive surgery K using the base curve of the contact lens in diopters (BC), the power of the contact lens (P), and manifest refraction (MRx, prescription without the lens), and over-refraction (ORx, additional correction needed with the lens). Its main limitation is the reliability of refraction in a patient with cataract.[29]

K postReSx = BC + P + (ORx - MRx)

- Vertexed IOL Method—The vertexed IOL method is based on a theoretical study by Feiz, Latkany, and colleagues, in which various nomograms were developed after calculating IOL power post-LASIK using SRK/T and other formulas; the change in spherical equivalent after LASIK is used to modify the IOL power. This method is limited by its theoretical nature and the lack of large published data to support its accuracy.

- Intraoperative Auto-Refraction Measurement—This method directly uses intraoperative refraction data to calculate the IOL power, without needing to know AL or K, and utilizes a special “A-constant.” It is also limited by the lack of support by large data studies.[29]

- DBR Method—Similar to the calculation method, the DBR method requires both preoperative (refraction, keratometry, AL, IOL power for emmetropia) and postoperative (refraction plane, residual refractive error after stabilization of refraction) data. The co-relationship shown below is then used to obtain the IOL power after refractive surgery.[7]

0.7D change at spectacle plane = 1.0D change at IOL plane.

Direct Methods

Direct methods actually measure the corneal power postoperatively and use it to calculate the effective keratometric diopters. Although most modern devices do not directly measure the posterior corneal curvature, they use alternative algorithms to approximate the induced RI change or use different variables to predict ELP. [30]

- Gaussian Optics and Linear Regression—The Gaussian formula uses the anterior and posterior radii of curvature; RI of air (1.0), anterior K (1.376), and aqueous humor (1.336); and corneal thickness. To calculate the effective refractive power (EffRP), the posterior corneal curvature is predicted based on data from studies by Oslen et al (rather than directly measured).[31] Effective RP is then used to predict ELP, along with the application of linear regression analysis.[32] Errors of nearly 0.5 D can be noted.

- Topography Method—This method uses the keratometric reading and flattest corneal power in the central 3-mm zone to calculate simulated K (SimK), which is then used to predict ELP. Errors occur due to steeper K values of the central zone.[33] The Maloney topographic method uses SimK obtained via topography, with the K reading then used to predict the IOL power:[34]

K = 376/ (337.5/SimK) – 5.5

- Aramberri “Double K” Method—Aramberri reported in 2002 that the flatter K should not be used in modern formulas and instead uses two K values: the preoperative K is used to predict ELP, while the postoperative K is incorporated in the formula for actual IOL power prediction. This formula was later incorporated in the Holladay 2 vergence calculation formula.[35][36]

- Camellin & Calossi—In Camellin and Clossi's formula, induced refractive change and anterior and posterior curvature of the cornea are used to predict IOL power.[37]

- Rosa Method—This method uses a correction factor (R factor) for corneal radius that was derived from a regression formula and then compared with the calculation method and double K method. In a study involving 19 eyes, measurements using the R factor were superior when used in the SRK/T and Holladay 1 formulas. The actual formula for IOL power is derived from manual measurements of corneal power (K) and axial length (AL).[38][39]

K = (0.0276 x AL + 0.3635) manual K

- Direct Measurements of Anterior & Posterior Corneal Power—With the invention of newer instruments, direct measurement of the posterior corneal power is also possible, which results in improved IOL power calculation accuracy after refractive surgery. The Orbscan and the Pentacam devices have been used to measure posterior corneal power, with the Pentacam appearing to have a slight advantage, though more investigation is needed.[40] [41] [42]

Despite the various methods described, the science of IOL power calculation after refractive surgery is still in its nascent stages and needs more research. Generally, the calculation method is considered to be most accurate, followed by corneal topography and automated K.[5]

In Corneal Transplants

It is extremely difficult to accurately predict corneal power in patients who have received a corneal transplant. If a triple procedure is planned, it is suggested that K readings of the fellow eye be used. An alternative is to use the average K readings from a series of previous transplants. If there is a corneal scar but no graft is planned, the fellow eye readings can be used or the power can be calculated using the AL and refractive error of the affected eye.[43][44]

For Piggy-Back IOLs

In patients with post–IOL implantation refractive surprise or those with a large dioptric requirement, a piggy-back IOL (a second IOL) can be placed in the sulcus along with the primary IOL in the capsular bag. This method does not require knowledge of the power of the primary implant or of the axial length, though minor adjustments are needed:

- Myopic correction: P = 1.0 × Error

- Hyperopic correction: P = 1.5 × Error

P = the required power in the piggy-back lens

Error = the residual refractive error that needs to be corrected [45] [46]

Errors and Mistakes

Pitfalls and Limits of Biometry

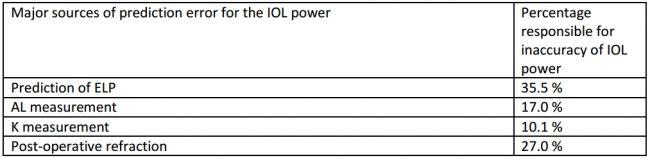

Calculation of IOL power is not absolute due to the large number of individual variations among human eyes. Several major sources of error have been documented in a study by Norrby et al (Table 6).[47]

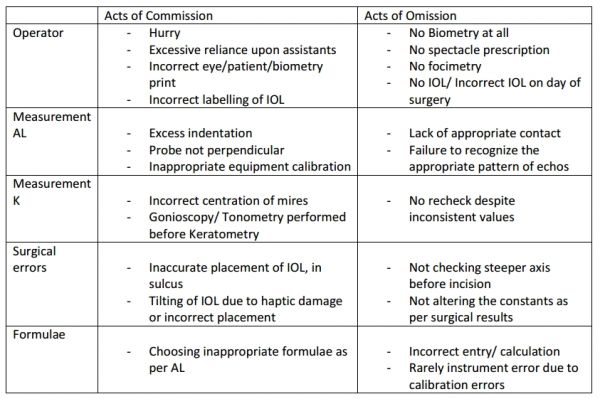

Acts of omission and commission can also lead to errors (Table 7).[48][1]

Improving Outcomes

Albeit not perfect, the precision of biometry for IOL power calculation can be improved by following some simple guidelines.

Patient Counselling

Not all patients may want emmetropia, and for some it may not be possible (e.g., those with very dense cataracts, where macular lesions can be missed). Appropriate counselling about the available options will suite each patient's needs is a necessity.

General Recommendations

Each surgeon should review their own results and make alterations to biometry, if needed. Regular checks and audits are a good habit; training and monitoring of staff is equally important. Ensure each patient's eye and all papers are in order; cross-checking with refraction is also a good adjunct if accurate retinoscopy is available. When performing the actual scan, ensure asepsis, especially in contact procedures. Patient comfort and appropriate anesthesia should be monitored.

AL Measurement

Optical biometry is the gold standard for AL measurement due to its ease of use, accuracy, reproducibility, and non-contact nature. In situations where it cannot provide accurate measurements (e.g., dense cataracts), it can be supplemented with ultrasonography methods to improve outcomes. Immersion ultrasonography is preferred, as it approaches the accuracy of optical methods, but it is cumbersome to use. When immersion is not available, contact ultrasonography can still be utilized. Appropriate machine calibration is necessary before the scan itself.

Qualities of a Good A-Scan Graph:

- Corneal echo appears as a tall single spike

- No echoes from aqueous humor or vitreous cavity

- Anterior and posterior lens capsule produce tall echoes

- Retina produces tall, sharply rising spike with no staircase at origin

- Orbital fat produces medium-to-low echoes

If the spike from the retina is not followed by multiple small spikes, it means you are hitting optic nerve; discard that reading. Also discard A scans in which the anterior chamber depth and actual length reduce, as this indicates that you are compressing the cornea. To achieve good spikes and improve accuracy, you should set gain to the minimum possible and use 8–10 measurements on average.

Tips for Contact Procedures:

- Probe should be perpendicular, centered and pointing towards macula

- Ensure no fluid between the probe and cornea

- Ensure no depression of cornea

K Measurement

The K value can be calculated using either automated or manual methods. Performing a double check using both methods helps to improve accuracy.

Tips for K Measurement:

- Do not perform other contact procedures before keratometry

- Use topical anesthetic before scanning

- Calibrate keratometer before scanning

- Take an average of 3 readings

- In the case of discrepancy, ask a second person to cross check

- Compare the refraction, especially the axis, with the K values

- Repeat if the difference is more than 1.0 D between the two eyes

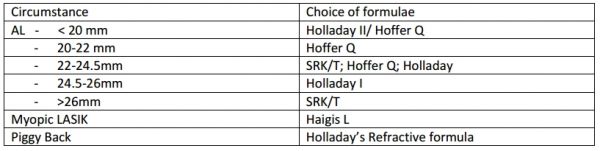

Choice of Formulas

Albeit controversial, some guidelines have been developed that may help guide which formulas to use under specific circumstances (Table 8). Note that some previously widely used formulas are now largely obsolete (e.g., the SRK 2). Regardless of the formula, appropriate setting calibration and adjustment of constants is necessary prior to IOL power prediction. No single formula has been found to be useful in all circumstances.

Some newer formulas (e.g., the T2 modification of SRK/T, Olsen, Hollady 2, Haigis) are still not widely available in the biometry software. Due to the absence of compelling comparative evidence of superiority among these options, it is justifiable to continue using an appropriate combination (according to axial length) of the two variable–single constant formulas.[1][47][48][49]

Future Trends

As technology and patient expectations increase, it is important to continue looking to improve our IOL calculation precision.

Formulas

- Utilizing the Holladay 2 formula, the Holladay IOL consultant (HIC) program performs complex power calculation for the surgeon (though availability of the HIC is not widespread)

- Olsen formula uses preoperative refraction and lens thickness to improve accuracy[49]

- Barrett II universal, a newer vergence-based formula, utilizes 5 variables to greatly improve post–cataract surgery refractive outcomes over older formulas

- The Hill-RBF formula, powered by artificial intelligence, also shows great promise in optimizing refractive outcomes[50]

Software

Okulix is a biometric computer program to simulate whole pseudophakic eyes with the goals of reducing calculation errors and ensuring a more reliable estimation of IOL strength. This approach separates the errors due to measurement and those due to calculation.[48] The Olsen and Okulix formulas utilize ray-tracing, which accounts for aberrations throughout the visual system, an added benefit.

Newer Machines

The Pentacam and Orbscan devices that have been used widely for corneal ectasia are beginning to be utilized for precise preoperative corneal power measurements.[26] Intraoperative aberrometry is another advancement that can be used to confirm and improve IOL calculation accuracy. The Optiwave Refractive Analysis device (ORA by Alcon) is an example of this aberrometry technology, with demonstrated accuracy at least equal to the advanced Barrett and Hill-RBF formulas and potential specialty use for complex cases such as post-refractive situations and toric IOL implantation.[51]

IOL Tolerance Adjustments

It has been suggested that manufacturers reduce the internal tolerance ranges for their IOLs to ±0.25 D, thereby improving accuracy and minimizing refractive surprises. However, manufacturers do not routinely disclose these parameters to clinicians.[49]

Additional Resources

Many options are now available for references as well as direct IOL calculations. Some of these are listed below.

The eye calculator software can be very useful in training institutes, as it is also usable offline.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Astbury N. and Ramamurthy B., How to avoid mistakes in biometry, Community Eye Health. 2006 Dec; 19(60): 70–71.

- ↑ Fedorov SN, Kolinko AI, Kolinko AI. Estimation of optical power of the intraocular lens. Vestn Oftalmol 1967;80:27–31

- ↑ Hoffer KJ. The Hoffer Q formula: a comparison of theoretic and regression formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg 1993;19:700–12.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sahin A, Hamrah P. Clinically relevant biometry. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:47–53. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834cd63e.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Frank W. Howes, Patient Workup for Cataract Surgery: Chapter 5.3, Ophthalmology, 4th Edition | Myron Yanoff, Jay Duker

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Holladay JT. Standardizing constants for ultrasonic biometry, keratometry, and intraocular lens power calculations. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23(9):1356-1370

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 A. K. Khurana, Intraocular Lenses: Optical aspects and Power calculation: Chapter 9, Theory and Practice of Optics and Refraction, 2nd edition A. K. Khurana

- ↑ Hoffer KJ. The Hoffer Q formula: a comparison of theoretic and regression formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg 1993;19:700–12.

- ↑ Olsen T, Corydon L, Gimbel H. Intraocular lens power calculation with an improved anterior chamber depth prediction algorithm. J Cataract Refract Surg 1995;21:313–9.

- ↑ Hoffer KJ. Modern TOL power calculations: Avoiding error and planning for special circumstances. Focal Points: Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 1999, module 12

- ↑ Haigis 'vv. The Haigis formula. Intraocular Lens Power Calculations. Shammas H], ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Inc; 2003:chap 5, pp 41-57

- ↑ Lowe RF, Clark BA. Posterior corneal curvature. Br J Ophthalmol. 1973;57:464–70.

- ↑ Bhardwaj V, Rajeshbhai GP. Axial Length, Anterior Chamber Depth-A Study in Different Age Groups and Refractive Errors. Journal of Clinical And Diagnostic Research. 2013;7(10):2211–12.

- ↑ Haigis W, Lege B, Miller N, et al. Comparison of immersion ultrasound biometry and partial coherence interferometry for intraocular lens calculation according to Haigis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000;238:765–73.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Rajan MS, Keilhorn I, Bell JA. Partial coherence laser interferometry vs conventional ultrasound biometry in intraocular lens power calculations. Eye 2002; 16:552–6.

- ↑ Montés-Micó R, Carones F, Buttacchio A, et al. Comparison of Immersion Ultrasound, Partial Coherence Interferometry, and Low Coherence Reflectometry for Ocular Biometry in Cataract Patients. Journal of Refractive Surgery. 2011:1–7.

- ↑ Posterior Iris Fixation of the Iris-Claw intra-ocular lens implantation through a scleral tunnel incision. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144(4):586–91

- ↑ Fedorov SN, Galin MA, Linksz A. A calculation of the optical power of intraocular lenses. Invest Ophthalmol 1975;14:625–8.

- ↑ Haigis W. Pseudophakic correction factors for optical biometry. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001 Aug;239(8):589-98.

- ↑ Holladay JT, Praeger TC: Accurate ultrasonic biometry in pseudophakia. (letter). Am J Ophthalmol 1993; 115(4): 536 – 537

- ↑ van Balen AT, Koole FD. Lens implantation in children. Ophthalmic Pediatr Genet 1988;9:121–125.

- ↑ Dahan E, Drusedau MUH. Choice of lens and dioptric power in pediatric pseudophakia. J Cataract Refract Surg 1997;23(Suppl.):S618–S623.

- ↑ Dahan E, Drusedau MUH. Choice of lens and dioptric power in pediatric pseudophakia. J Cataract Refract Surg 1997; 23 :618–23.

- ↑ Wilson ME, Peterseim MW, Englert JA, et al. Pseudophakia and polypseudophakia in the first year of life. J AAPOS 2001;5:238–245.

- ↑ Byrne SF. A-scan axial eye length measurements. Mars Hill (NC): Grove Park Publishers; 1995.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Thomas C. Prager, PhD, MPHa,*, David R. Hardten, MDb,c, Benjamin J. Fogal, OD : Enhancing Intraocular Lens Outcome Precision: An Evaluation of Axial Length Determinations, Keratometry, and IOL Formulas, Ophthalmol Clin N Am 19 (2006) 435–448

- ↑ Neal H. Atebara, MD; Penny A. Asbell, MD; Dimitri T. Azar, MD; Forrest j. Ellis, Intraocular Lenses, Chapter 6. Clinical Optics, BCSC AAO 2011-2012

- ↑ Holladay JT. IOL calculations following RK. J Refract Corneal Surg 1989;5:203.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Haigis W. Corneal power after refractive surgery for myopia: contact lens method. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:1397–411.

- ↑ Hamilton DR, Hardten DR. Cataract surgery in patients with prior refractive surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2003;14:44–53.

- ↑ Olsen T. On the calculation of power from curvature of the cornea. Br J Ophthalmol 1986;70:152–4.

- ↑ Hamed AM, Wang L, Misra M, et al. A comparative analysis of five methods of determining corneal refractive power in eyes that have undergone myopic laser in situ keratomileusis. Ophthalmology 2002; 109:651–8.

- ↑ Latkany RA, Chokshi AR, Speaker MG, et al. Intraocular lens calculations after refractive surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31:562–70.

- ↑ Wang L, Booth MA, Koch DD. Comparison of intraocular lens power calculation methods in eyes that have undergone laser-assisted in-situ keratomileusis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2004;102:189–96 [discussion: 196–7]

- ↑ Hoffer KJ. Clinical results using the Holladay 2 intraocular lens power formula. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:1233–7.

- ↑ Aramberri J. Intraocular lens power calculation after corneal refractive surgery: double-K method. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:2063–8.

- ↑ Camellin M, Calossi A. A new formula for intraocular lens power calculaton after refractive corneal surgery. J Refract Surg 2006;22:187–99.

- ↑ Rosa N, Iura A, Romano M, et al. Correlation between automated and subjective refraction before and after photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg 2002;18:449–53

- ↑ Rosa N, Capasso L, Lanza M, et al. Reliability of a new correcting factor in calculating intraocular lens power after refractive corneal surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31:1020–4.

- ↑ Boscia F, La Tegola MG, Alessio G, et al. Accurac of Orbscan optical pachymetry in corneas with haze. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28:253–8.

- ↑ Prisant O, Calderon N, Chastang P, et al. Reliability of pachymetric measurements using Orbscan after excimer refractive surgery. Ophthalmology 2003; 110:511–5.

- ↑ Srivannaboon S, Reinstein DZ, Sutton HF, et al. Accuracy of Orbscan total optical power maps in detecting refractive change after myopic laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999; 25:1596–9.

- ↑ Geggel HS. Intraocular lens implantation after penetrating keratoplasty. Improved unaided visual acuity, astigmatism, and safety in patients with combined corneal disease and cataract. Ophthalmology. t990;97(11): t460- 1467.

- ↑ Hoffer KJ. Triple procedure for intraocular lens exchange. Arch Ophtha/rnol. 1987; 105(5): 609- 610.

- ↑ Findl O , Menapace R. Piggyback intraocular lenses [letter].JCataract Refract SLlrg. 2000;26(3): 308~30 9.

- ↑ Findl O , Menapace R, Rainer G, Georgopoulos M. Contact zone of piggyback acrylic intraocular lenses. Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25(6):860- 862.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Norrby S. Sources of error in intraocular lens power calculation. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008; 34: 368–376.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Dr. Rajesh Kapoor, Dr. Ajay Dudani, Dr.Vinod Goyel, HIGH PRECISION BIOMETRY: Avoiding surprises in Cataract surgery ; Journal of the Bombay Ophthalmologists’ Association : Jan - Mar 2002 Vol. 12 No. 1.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 R Sheard, Optimising biometry for cataract surgery, Cambridge Ophthalmological Symposium, Eye (2014) 28, 118–125

- ↑ Hill WE, Abuladia A, Wang L, Koch DD. Pursuing perfection in IOL calculations. II. Measurement foibles: Measurement errors, validation criteria, IOL constants, and lane length. K Cataract Refractive Surgery 2017:43;7;869-70.

- ↑ Raufi N, Charlene J, Anthony K, Vann R. Intraoperative aberrometry vs modern preoperative formulas in predicting intraocular lens power. JCRS. PAP (Accepted March 11.2020).

- Binkhorst RD. Intraocular lens power calculation manual. A guide to the author’s TI 58/59 IOL power module. 2nd ed. New York: Richard D Binkhorst; 1981.

- Ram J, Pandav SS, Ram B, et al. Systemic disorders in age related cataract patients. Int Ophthalmol 1994;18:121–5.

- Ianchulev T, Salz J, Hoffer K, et al. Intraoperative optical refractive biometry for intraocular lens power estimation without axial length and keratometry measurements. J Cataract Refract Surg 2005;31: 1530–6.