Fish Skin Xenografts in Oculoplastic Surgery

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Fish skin xenografts (FSGs) are an emerging biologic graft option in oculoplastic surgery that combines preserved extracellular matrix with naturally occurring bioactive lipids, offering a potentially less invasive alternative to traditional skin grafts. When grafted, it serves as an extracellular matrix, providing a scaffold for the body's own cells and blood vessels to grow into and regenerate living tissue, often resulting in faster healing. Early periocular clinical applications include a pilot series in post-Mohs defects and a challenging reconstructive case after periorbital necrotizing fasciitis. Clinical results and outcomes from both studies suggest that FSGs can support wound healing with satisfactory functional and cosmetic results, making them a promising option for further research and broader reconstructive use.

Introduction

Fish skin xenografts (FSGs) represent an innovative biologic scaffold that has emerged as a transformative option in wound healing across many surgical specialties including Ophthalmology and specifically Oculoplastics.[1][2] Derived from the skin of the North Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), these acellular grafts have gained U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and demonstrated clinical efficacy in treating a wide spectrum of wounds, from chronic diabetic ulcers to acute traumatic injuries.[3][4] The application of FSGs in Oculoplastics, while relatively recent, builds upon a growing body of evidence from general wound care and plastic surgery that highlights their unique regenerative properties, favorable safety profile, and practical advantages over traditional reconstruction methods.

The periocular region presents unique challenges for reconstruction following tumor excision, trauma, or infection. Traditional approaches including healing by secondary intention, primary closure, local flaps, and autologous grafting each carry specific limitations, including donor site morbidity, extended healing times, or suboptimal cosmetic outcomes in challenging anatomic locations.[5] FSGs offer a novel scaffold solution that addresses many of these limitations while introducing distinctive biological advantages derived from their preserved omega-3 fatty acid content and structural similarity to human dermis.

Development and Regulatory Status

Product Development

The development of intact FSGs for medical use originated in Isafjordur, Iceland, where Kerecis, a medical device company, pioneered the processing of Atlantic cod skin into a viable biomaterial for human tissue regeneration. The choice of Atlantic cod was strategic: this species is farmed in the pristine waters surrounding Iceland under controlled conditions, ensuring consistent quality and traceability. Importantly, there are no known prion, bacterial, or viral diseases that can be transmitted from North Atlantic cod to humans, eliminating a major safety concern that necessitates extensive viral inactivation procedures for mammalian-derived products.[6]

The processing methodology represents a key innovation. Unlike mammalian tissue products that require harsh chemical and irradiation treatments to eliminate disease transmission risks, procedures that often destroy beneficial bioactive components, fish skin undergoes minimal processing using a proprietary patented method.[7] This gentle processing achieves cell lysis through osmotic mechanisms while preserving the three-dimensional structure, mechanical properties, lipid composition, and protein matrix of the native tissue. The result is a product that retains significantly more of its natural bioactive components compared to conventional dermis substitutes.

Regulatory Approval Timeline

- 2013: The U.S. FDA granted 510(k) clearance to the Kerecis® Omega-3 Wound product for treatment of partial- and full-thickness wounds, including pressure ulcers, vascular ulcers, diabetes-related ulcers, traumatic wounds, surgical wounds, and burns.[8] This initial clearance was based on the product's substantial equivalence to existing wound care devices and preliminary clinical data demonstrating safety and efficacy.

- 2021: The U.S. FDA approved Kerecis® Omega3 SurgiBind specifically for surgical use in plastic and reconstructive surgery.[9] This approval represented an expansion of indications and reflected accumulating evidence of the graft's utility in more complex reconstructive scenarios requiring active tissue regeneration rather than simple wound coverage.

The product has also obtained CE (Conformité Européenne) marking in Europe and is manufactured according to ISO13485 quality standards and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards. These certifications have facilitated adoption in international markets and contributed to a growing body of clinical experience across diverse geographic and patient populations.

Source Material and Biochemical Composition

North Atlantic Cod

The North Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) inhabits the cold, pristine waters of the North Atlantic Ocean, particularly around Iceland. These fish are farmed under strictly controlled conditions that ensure consistent quality, prevent contamination, and allow complete traceability from source to final product. The selection of this species offers several distinct advantages:

- Disease Safety: As previously noted, there is no known risk of prion, bacterial, or viral disease transmission from cod to humans currently reported in the literature. This safety profile eliminates the need for harsh viral inactivation procedures that can denature proteins, destroy growth factors, and alter the structural integrity of the tissue. The absence of zoonotic disease risk represents a fundamental advantage over mammalian-derived products, which carry theoretical (albeit low) risks of transmitting bovine spongiform encephalopathy from bovine products or porcine endogenous retroviruses from porcine products.[6][7]

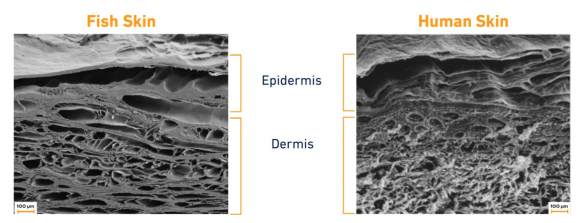

- Skin Structure: The dermis of Atlantic cod exhibits a collagen fiber architecture and mechanical properties that closely mimic human skin, despite being evolutionarily distant (Figure 1). This structural similarity facilitates integration into human tissue and provides appropriate mechanical support during the healing process.

- Lipid Composition: Unlike mammalian species, cold-water fish accumulate high concentrations of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in their tissues as an adaptive mechanism to maintain membrane fluidity in cold environments. This naturally occurring omega-3 enrichment provides bioactive components that actively modulate the healing process, as further detailed below.

Structural Materials

The acellular fish skin matrix contains multiple components that contribute to its regenerative properties and the main ones are listed below.[10][11]

- Type I Collagen: The primary structural protein, arranged in a three-dimensional fibrillar network that provides tensile strength and serves as a scaffold for cellular attachment and migration.

- Proteoglycans and Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs): These large molecules regulate water content, provide compressive resistance, and modulate cellular behavior through interactions with growth factors and cytokines. Specific GAGs present include heparan sulfate, dermatan sulfate, and hyaluronic acid.

- Elastin: Provides elastic recoil and compliance, contributing to the mechanical behavior of the graft during wound contraction and tissue remodeling.

- Laminin and Fibronectin: Adhesive glycoproteins that facilitate cellular attachment to the collagen matrix and promote cell migration during wound healing.

- Soluble Collagens: Smaller molecular weight collagens that can signal cellular differentiation and matrix remodeling.

The porous three-dimensional architecture of the processed fish skin is crucial for its function. The interconnected pore structure, with pore sizes ranging from approximately 20-100 micrometers, allows infiltration of host cells, ingrowth of blood vessels, and diffusion of nutrients and waste products.[10] This porosity, combined with the preserved extracellular matrix proteins, creates an optimal environment for tissue regeneration.

Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of FSGs is their high content of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, specifically eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 n-3).[12] Quantitative analysis has demonstrated that fish skin contains significantly higher omega-3 concentrations compared to human skin, human amnion membrane, and bovine or porcine collagen matrices.

These omega-3 fatty acids are not merely passive structural components; they actively participate in wound healing through multiple mechanisms:

- Anti-inflammatory Signaling: Omega-3 PUFAs serve as precursors for specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), including resolvins, protectins, and maresins. These bioactive lipid mediators actively resolve inflammation rather than simply suppressing it, facilitating the transition from the inflammatory phase to the proliferative phase of healing. In vitro studies using human keratinocytes have demonstrated that omega-3-rich fish skin activates SPM pathways, leading to reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and enhanced production of growth factors that promote epithelialization.[12]

- Antimicrobial Activity: Omega-3 fatty acids and their metabolites exhibit direct antimicrobial effects against common wound pathogens. This property may contribute to the low infection rates observed in clinical studies using fish skin grafts, despite application to contaminated or potentially contaminated wounds. [13] The antimicrobial activity appears to result from multiple mechanisms, including disruption of bacterial membranes, modulation of host immune responses, and alteration of the local wound environment to favor healing over infection.

- Cellular Proliferation and Migration: Omega-3 fatty acids have been shown to enhance fibroblast proliferation, keratinocyte migration, and angiogenesis – all critical processes in wound healing. The mechanisms involve modulation of cell membrane composition, alterations in lipid raft signaling platforms, and direct effects on gene expression through nuclear receptors.[14]

- Pain Reduction: Clinical observations across multiple studies have consistently noted decreased pain levels in patients treated with fish skin grafts compared to conventional dressings or other skin substitutes.[15][16] The mechanism underlying this analgesic effect likely involves omega-3-mediated modulation of inflammatory pain pathways and reduced production of pro-inflammatory mediators that sensitize nociceptors.

The preservation of these bioactive lipids in FSGs represents a significant advantage over mammalian-derived products, which lose much of their lipid content during the harsh processing required for viral inactivation.

Applications in Oculoplastics

First Clinical Series

The introduction of FSGs to oculoplastic surgery occurred recently, with the first published clinical series appearing in 2024.[2] Wang et al. reported outcomes in 6 patients treated between January 2022 and December 2023 for periocular anterior lamella skin defects following Mohs excision of non-melanoma skin cancers. This retrospective pilot series represents the first description of acellular FSG use specifically for periocular reconstruction.

Study Population

- 6 patients (3 females, 3 males).

- Mean age 60.8 years (range 44–80).

- Histologic diagnoses: basal cell carcinoma (4 patients) and squamous cell carcinoma (2 patients).

- Defect locations: eyebrow (3 cases), lateral nasal wall (1 case), lower eyelid (1 case), and one medial lower eyelid/nasal wall case (Figures 2-4).

- Defect sizes ranged from 8 × 10 mm to 30 × 40 mm.

Five patients underwent reconstruction on the same day as Mohs surgery in a clinic minor procedure room. One patient with a large lower eyelid basal cell carcinoma and septal violation, along with multiple additional facial Mohs defects, underwent reconstruction in the operating room one day after Mohs surgery.[2]

Surgical Technique

The authors described a standardized technique adapted for periocular application. First, the wound edges and bed were freshened using a #15 blade to remove desiccated tissue and expose viable dermis. The defect was measured, and the FSG (Kerecis® Omega3 Wound) was cut to size.

The graft was available either as loose micrografts or as a solid meshed sheet. The sheet xenograft was placed in sterile saline for approximately one minute prior to application to improve pliability. For deeper defects, particularly in areas such as the brow or cheek, micrografts were placed in a single layer to fill the wound bed before placement of a meshed sheet. For superficial defects, a meshed sheet alone was sufficient.

The edges of the FSG were secured to the surrounding skin using four interrupted 5-0 polyglactin sutures, followed by a circumferential running 5-0 poliglecaprone suture. In concave locations such as the medial canthal region or along the nasal sidewall, a 5-mm central buttonhole was created in the graft to prevent seroma formation. A Xeroform bolster was sutured over the graft to maintain contact with the wound bed and was removed two weeks postoperatively. Patients were instructed to apply erythromycin ointment to the wound for one month.

Outcomes and Complications

Successful Cases (4 of 6, 67%)

Four patients achieved complete wound healing with a single graft application. Healing occurred through a combination of graft incorporation and secondary intention epithelialization at the graft edges. Cosmetic outcomes were evaluated using the Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating (SCAR) scale, with a mean score of 4.2 (range 3–7), indicating cosmetically acceptable results. Patients and families reported satisfaction with postoperative appearance. Functional outcomes were favorable, with no lid malposition, lagophthalmos, or ocular surface complications observed in these patients.[2]

Reapplication Required (2 of 6, 33%)

Two patients required graft reapplication due to incomplete wound granulation and epithelialization after the initial placement. One patient underwent a second application of FSG three weeks after the first and achieved full wound healing by four months after Mohs surgery. Another patient required a second application of FSG nine days after the initial placement to the medial portion of the wound only. A third application was subsequently applied using a tissue adhesive one week after the second application. These additional applications were performed to address incomplete granulation and epithelialization following the initial graft.[2]

Cicatricial Ectropion (1 of 6, 17%)

The patient that required 3 FSG applications presented with a large lower eyelid defect measuring 30 × 40 mm and associated septal violation. As mentioned above, he required two additional layers of xenograft (3 applications total) and subsequently developed a mild lower punctal cicatricial ectropion without lagophthalmos or corneal decompensation. This complication was subsequently repaired using a full-thickness skin graft. No additional postoperative complications were observed.[2]

Key Observations

- Two patients required more than one application of xenograft due to incomplete wound granulation and epithelialization.

- One patient developed mild lower punctal cicatricial ectropion; no other postoperative complications were observed.

- All patients achieved satisfactory wound healing and cosmetically acceptable results.

- The average follow-up time was 3.29 months (range 0.75–7.5 months) after initial xenograft application.

- The mean SCAR score was 4.2 (range 3–7).

Periorbital Necrotizing Fasciitis Case

In 2025, Shott et al. reported the first documented case describing the use of intact acellular FSGs for eyelid reconstruction following periorbital necrotizing fasciitis (NF), a rare and vision-threatening soft tissue infection requiring prompt antimicrobial therapy and extensive surgical debridement.[17] This case represents a substantially more complex reconstructive scenario than post-Mohs defects and was characterized by:

- Severe polymicrobial infection requiring broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics.

- Extensive tissue necrosis necessitating aggressive surgical debridement.

- Necrosis extending past the orbital septum of the lower eyelid.

- Need for staged reconstruction to restore eyelid form and function.

Clinical Course

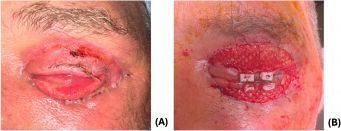

A 58-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder presented with rapidly progressive left facial and periorbital swelling and pain. Examination revealed marked periorbital edema, erythema, and eyelid skin necrosis. Laboratory studies demonstrated leukocytosis and elevated inflammatory markers. Blood cultures grew Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens. Initial imaging showed preseptal cellulitis; however, progression with gas in the soft tissues prompted urgent surgical debridement.[17]

The patient underwent extensive debridement of the upper and lower eyelids, with necrosis visualized past the orbital septum on the lower lid. Cultures obtained intraoperatively grew Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Following debridement and stabilization on intravenous antibiotics, the wounds demonstrated healthy granulation tissue.

Fish Skin Grafting

Eight days after debridement, the patient underwent in-office release of cicatrix and placement of intact acellular FSG (Kerecis® Omega3 Wound), secured with 5–0 monocryl sutures and accompanied by a temporary tarsorrhaphy (Figure 5). The FSG was used as a primary reconstructive modality for the upper eyelid and as an intermediate step for the lower eyelid, where cicatricial changes were more pronounced.

At two-week follow-up, the upper eyelid demonstrated good healing with improved lid closure. Due to integration of the graft and persistent cicatricial changes of the lower eyelid, additional FSG was applied after lysis of adhesions between the septum and inferior orbital rim and reformation of the lower fornix. Further FSG was sutured over the remaining lower eyelid wound.

Subsequent Reconstruction and Outcomes

Despite progressive healing, the patient developed residual lower eyelid ectropion. One month later, additional reconstruction was performed for recurrent septal scarring, including a lateral tarsal strip, medial spindle, and anterior lamellar full-thickness preauricular skin graft, along with temporary tarsorrhaphy. At follow-up, the patient exhibited mild lower eyelid ectropion and mild lagophthalmos without exposure keratopathy, maintaining a visual acuity of 20/25. Although further reconstruction was offered, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Clinical Significance

This case demonstrates the potential role of acellular FSGs as an adjunct in staged periocular reconstruction following necrotizing fasciitis, particularly for optimizing the wound bed and facilitating subsequent definitive repair. The authors emphasize that, despite graft use, cicatricial complications may still occur and require additional reconstruction. To their knowledge, this represents the first reported use of FSG for periocular wound reconstruction after necrotizing fasciitis.

Cost and Health Economic Considerations

Although no periocular-specific economic studies exist, wound healing economics from other studies utilizing FSGs provide useful context:

- A double-blind RCT found that treating wounds with fish skin grafts cost significantly less than treatment with a human amnion membrane product (76% lower overall cost) due to faster healing and fewer dressing changes.[18]

- Modeling studies in diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) indicate that fish skin treatment could result in lower costs ($11, 210 vs. $15, 075 per wound), more wounds healing (83.2% vs. 63.4%), fewer amputations (4.6% vs. 6.9%), and a higher quality of life (0.676 vs. 0.605 quality-adjusted life year [QALY]) than the Standard of Care.[18]

- One multicenter, randomized controlled trial evaluating the use of omega-3-rich acellular FSG compared with Collagen Alginate Therapy (CAT) found annual cost savings of approximately $2,800 per patient when using FSG vs CAT in DFU.[19]

These findings suggest that the higher unit cost of biologic xeno-materials may be offset by improved healing rates, reduced clinic visits, and fewer complications – a model that, if demonstrated in periocular surgery and oculoplastics, could influence reconstructive decision-making. However, further research is necessary in oculoplastics to determine the economic costs of FSG compared to the standard of care over time.

References

- ↑ Simmons B. Fish Skin Grafts May Be a Substitute for Other Skin Grafts Following Mohs Surgery. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published August 12, 2025. https://www.aao.org/education/editors-choice/fish-skin-grafts-may-be-substitute-other-skin-graf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Wang D, Maliakkal J, Sadat O, Codrea V, Nguyen J. Acellular Fish Skin Grafts for Treatment of Periocular Skin Defects. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;40(6):681-684. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000002699

- ↑ Zhao C, Feng M, Gluchman M, Ma X, Li J, Wang H. Acellular fish skin grafts in the treatment of diabetic wounds: Advantages and clinical translation. J Diabetes. 2024;16(5):e13554. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.13554

- ↑ Karhana S, Khan MA. Omega-3 Acellular Fish Skin Grafts for Chronic and Complicated Wounds: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2025;15(2):4945. Published 2025 Apr 1. doi:10.5826/dpc.1502a4945

- ↑ Rajabi MT, Rafizadeh SM, Sadeghi R, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of flap reconstruction in periocular repair: outcomes, complications, and future directions. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025;25(1):653. Published 2025 Nov 20. doi:10.1186/s12886-025-04512-y

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Di Mitri M, Di Carmine A, Thomas E, et al. Fish Skin Graft: Narrative Review and First Application for Abdominal Wall Dehiscence in Children. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2023;11(9):e5244. Published 2023 Sep 14. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000005244

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fish Skin Technology - Kerecis. Intact Fish Skin for Tissue Regeneration | Kerecis. Published May 20, 2021. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.kerecis.com/fish-skin-technology/?utm_

- ↑ FDA Clears Fish-Skin Technology to Heal Human Wounds - Kerecis |. Published November 7, 2013. https://www.kerecis.com/fda-clears-fish-skin-technology-to-heal-human-wounds/

- ↑ Kerecis Announces First-Ever Fish-Skin Implantable Medical Product for Surgery - Kerecis. Intact Fish Skin for Tissue Regeneration | Kerecis. Published October 19, 2021. https://www.kerecis.com/surgibind-implantable-for-surgery/

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Esmaeili A, Biazar E, Ebrahimi M, Heidari Keshel S, Kheilnezhad B, Saeedi Landi F. Acellular fish skin for wound healing. Int Wound J. 2023;20(7):2924-2941. doi:10.1111/iwj.14158

- ↑ Chen W, Chen M, Chen S, et al. Decellularization of fish tissues for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications. Regen Biomater. 2024;12:rbae138. Published 2024 Nov 28. doi:10.1093/rb/rbae138

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Seth N, Chopra D, Lev-Tov H. Fish Skin Grafts with Omega-3 for Treatment of Chronic Wounds: Exploring the Role of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Wound Healing and A Review of Clinical Healing Outcomes. Surg Technol Int. 2022;40:38-46. doi:10.52198/22.STI.40.WH1494

- ↑ Karhana S, Khan MA. Omega-3 Acellular Fish Skin Grafts for Chronic and Complicated Wounds: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2025;15(2):4945. Published 2025 Apr 1. doi:10.5826/dpc.1502a4945

- ↑ Ahmadi AR, Shirani F, Abiri B, Siavash M, Haghighi S, Akbari M. Impact of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation on the gene expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors-γ, α and fibroblast growth factor-21 serum levels in patients with various presentation of metabolic conditions: a GRADE assessed systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of clinical trials. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1202688. Published 2023 Nov 15. doi:10.3389/fnut.2023.1202688

- ↑ Ibrahim M, Ayyoubi HS, Alkhairi LA, Tabbaa H, Elkins I, Narvel R. Fish Skin Grafts Versus Alternative Wound Dressings in Wound Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cureus. 2023;15(3):e36348. Published 2023 Mar 19. doi:10.7759/cureus.36348

- ↑ Ivana J, Sanjaya IGPH. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Fish Skin Grafts as Wound Dressings: A Systematic Review. European Burn Journal. 2025; 6(3):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj6030050

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Shott M, Wang D, Nguyen J. Case Report: Eyelid reconstruction using intact fish skin xenograft following periorbital necrotizing fasciitis. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne). 2025;5:1589771. Published 2025 May 22. doi:10.3389/fopht.2025.1589771

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Winters C, Kirsner RS, Margolis DJ, Lantis JC. Cost Effectiveness of Fish Skin Grafts Versus Standard of Care on Wound Healing of Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Retrospective Comparative Cohort Study. Wounds. 2020;32(10):283-290.

- ↑ Lantis Ii JC, Lullove EJ, Liden B, et al. Final efficacy and cost analysis of a fish skin graft vs standard of care in the management of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial. Wounds. 2023;35(4):71-79. doi:10.25270/wnds/22094