History of Oculoplastics

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

This article traces the historical evolution of oculoplastic surgery from its earliest descriptions in antiquity to its development as a modern subspecialty shaped by reconstructive needs, anatomical insight, and technological advances. Learn about the origins and refinement of key procedures in eyelid reconstruction, ptosis repair, lacrimal surgery, orbital implants, decompression, and imaging. By contextualizing contemporary oculoplastic practice within its historical and surgical foundations, this article highlights how past innovations continue to inform modern ophthalmic care.

Introduction

The development of oculoplastic surgery reflects the cumulative contributions of multiple surgical disciplines over centuries. References to oculoplastic surgery date back to the Code of Hammurabi (circa 2250 BC), which includes one of the earliest descriptions of treatment for an infected lacrimal sac. Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BC–50 AD) made foundational contributions by describing advancement flaps, sliding flaps, and the island pedicle flap, establishing reconstructive principles that remain relevant today. After a prolonged period of limited innovation, Carl Ferdinand von Graefe revived and refined classical eyelid repair techniques in the early 19th century.

Modern oculoplastic surgery was profoundly shaped by war. Armed conflict acted as a catalyst for rapid surgical innovation, particularly during World War II, when the volume and severity of facial trauma and burns overwhelmed plastic surgeons and led to the delegation of eyelid and orbital injuries to ophthalmologists. These injuries were often unfamiliar to surgeons trained primarily in cataract, glaucoma, and strabismus, forcing the development of new soft tissue and reconstructive techniques. The resulting advances in anatomical understanding and surgical methods established oculoplastic surgery as a distinct subspecialty that now encompasses reconstructive eyelid and orbital surgery, management of lacrimal disorders, treatment of orbital disease and socket deformities, and modern periocular aesthetic surgery.[1]

Eyelid Reconstruction

One of the first surgeons credited with modern periorbital reconstructive surgery was Carl Ferdinand von Graefe, who performed the first blepharoplasty in 1809, during which he used a pedicle flap from adjacent cheek skin to reconstruct a lower eyelid affected by gangrene. Later in the 19th century, in 1829, Johan Karl Fricke described a monopedicled flap, which was later named after him to Fricke flap, based on the temporal region for reconstruction of eyelid defects. In this approach, skin above the eyebrow is moved to cover the anterior lamellar defect. The flap is elevated subcutaneously to avoid deeper dissection in the temple area and reduce the risk of injuring the temporal branch of the facial nerve.[2]

Wendell Hughes introduced the tarsoconjunctival (Hughes) flap for full-thickness lower-lid defects, emphasizing replacement of posterior lamella with tarsus or conjunctiva and anterior lamella with skin or muscle. It involves attaching tissue from the upper eyelid to the lower eyelid, covering the affected eye for several weeks to allow for revascularization around the graft before separating the graft from the upper eyelid in a second procedure.[3] For upper-lid defects, an analogous technique known as the Cutler-Beard flap emerged in the mid-20th century. This procedure also involves utilizing skin or muscle flaps, which is advanced from the lower eyelid to the upper eyelid instead. Likewise, doing so covers the affected eye for several weeks before being separated.[4]

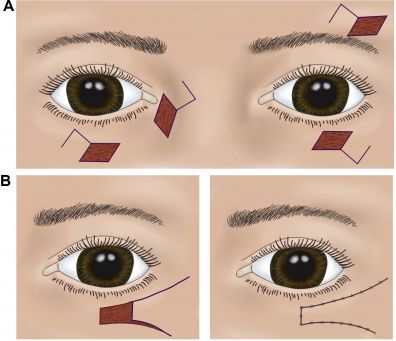

As surgical practice evolved, single-stage, local flaps became popular to avoid the inconvenience of two-stage eyelid-sharing. The Tenzel semicircular flap, which was first described in 1975, uses a laterally based skin-muscle flap rotated and advanced medially after lateral canthotomy and cantholysis, closing lower eyelid defects of up to half of the lid margin in a single step (Figure 1).[5] Similarly, anterior-lamella-only flaps like the Tripier flap (myocutaneous flap from the upper lid) were used for smaller defects that does not involve the posterior lamella, making reconstruction less invasive.[6] Finally, as reconstructive demands increased, particularly for extensive posterior-lamella loss, surgeons adopted grafts from non-eyelid tissues to replace tarsus/conjunctiva. Grafts of hard-palate mucosa, oral mucosa, auricular cartilage, and nasal septum have all been described and validated.[7] As cosmetic surgery demand grew in the late 20th century, eyelid surgery evolved from purely reconstructive aims toward aesthetic refinements.[8]

Ptosis Surgery

The earliest modern documented attempts at surgical correction of ptosis dates back to 1923. L. de Blaskovics described a method to correct ptosis without an intact superior rectus muscle by shortening the levator muscle via resecting part of the tarsus, producing an eyelid fold.[9] Around the same era, surgeons recognizing ptosis with functional superior rectus muscle developed sling-based approaches, in which a fascia lata sling gets attached to the tarsus.[10][11]

Later, with advances in understanding eyelid anatomy, aponeurotic repair (introduced by Lester T. Jones in 1975) became the dominant paradigm. Aponeurotic ptosis is the most common cause of ptosis, and because it is related to aging, this type of ptosis is often seen in the elderly.[11] These individuals typically have involutional changes of the aponeurosis such as stretching, dehiscence, or disinsertion. In aponeurotic repair, a skin incision is made approximately 7 mm above the eyelashes, cutting only through the skin and pretarsal orbicularis. The tissue is dissected until the preaponeurotic fat is exposed. After the aponeurosis is identified beneath the fat pad, the superior portion of the aponeurosis is attached to the distal portion.[12]

In parallel, the posterior approach, gained popularity. This was performed via Muller’s muscle conjunctival resection (MMCR) or “white-line advancement,” both of which corrects droopy eyelids by working through the conjunctiva, avoiding a skin incision and minimizing external dissection. In MMCR, a segment of conjunctiva and Muller’s muscle is resected, allowing posterior lamellar shortening and thereby elevating the lid. In the white-line advancement variant, the distal levator aponeurosis (the white-line) is identified after dissection of Muller’s muscle and conjunctiva, which is then advanced to the tarsus, restoring levator function.[13] This posterior route is especially appealing for patients with moderate to good levator function and when cosmetic concerns are important.[14] Over time, the posterior approach has evolved to modern conjunctival-sparing variants.[15]

Entropion

Early surgical correction of entropion dating back to 1300 years ago focused on mechanically rotating the eyelid margin outward by altering the balance between the anterior and posterior lamellae. Initial techniques relied on vertical everting sutures placed through the eyelid to temporarily evert the margin. Later methods introduced anterior lamellar recession, in which the skin and orbicularis muscle were dissected off the tarsus and repositioned superiorly to reduce inward rotational forces, particularly in trachomatous cases. As understanding of eyelid mechanics improved in the 19th and early 20th centuries, surgeons developed operations based on structural shortening and rotational change, including triangular resections of skin and tarsus combined with lateral canthotomy to alter lid tension and promote eversion.[1]

Modern entropion repair focuses on reinsertion of the lower eyelid retractors to restore vertical stability, often combined with horizontal tightening of the eyelid. Horizontal laxity is most commonly corrected using a lateral tarsal strip procedure, in which the lateral tarsus is isolated, shortened, and secured to the periosteum of the lateral orbital rim.[1] Current techniques may include a combination of lateral eyelid shortening, partial myectomy of the orbicularis oculi muscle to reduce inward rotational vectors, and excision of lower eyelid skin (Figure 2).[16]

Ectropion

Early ectropion surgery aimed to correct outward turning of the lower eyelid by shortening and supporting the lid. Initial techniques included suspension sutures to elevate the eyelid, sometimes relying on scar formation to maintain position, while other methods involved direct fixation to periosteum or tarsus. Surgeons later performed triangular excisions of skin and orbicularis muscle near the lateral canthus to tighten the anterior lamella and rotate the lid margin toward the globe. More aggressive procedures also involved excision of tarsal or conjunctival segments to shorten the posterior lamella; however, both anterior and posterior lamellar excisions could result in unnatural eyelid contour, prompting the development of skin-muscle flaps and Z-plasty techniques to redistribute tension more naturally.[1]

Modern ectropion repair focuses on restoring lamellar balance and addressing the underlying anatomical defects rather than simple skin excision. Horizontal eyelid laxity is most commonly corrected using the lateral tarsal strip procedure, which anchors the lateral tarsus to the orbital rim. Vertical support may be restored through reinsertion of the lower eyelid retractors, medial canthal tightening, full-thickness wedge resections, or scar release with skin grafting in cicatricial cases. These approaches collectively reestablish normal eyelid apposition to the globe and improve both function and cosmetic appearance.[1]

Blepharospasm

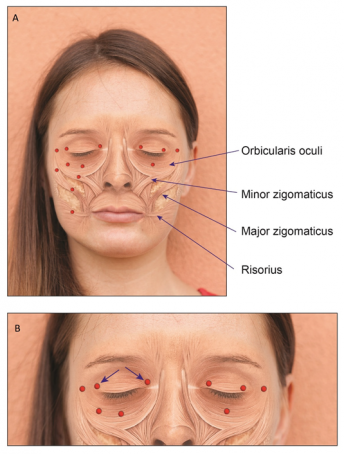

The first report of blepharospasm in the medical literature was by Mackenzie (1857)[17], although depictions in a Flemish Renaissance painting (De Gaper, circa 1560) attributed to Pieter Brueghel the elder suggest the condition was recognized as early as the 16th century. Early surgical strategies were largely destructive, focusing on facial nerve avulsion or excessive orbicularis muscle excision. Modern treatment of blepharospasm evolved during the mid-to-late 20th century.

A major therapeutic breakthrough occurred following Scott’s introduction of botulinum toxin A (Figure 3) in 1980, which dramatically improved medical management. Surgical care advanced further with the systematic anatomical approach of Gillum and Anderson in 1981, which addressed brow ptosis, levator disinsertion, lateral canthal laxity, dermatochalasis, and orbicularis spasm. Refinement of limited orbicularis myectomy techniques has since improved outcomes in carefully selected patients.[1]

Lacrimal Surgery

Surgical attempts to create a passage for tears go back nearly two millennia. Ancient physicians such as Celsus and Galen from the first and second centuries reportedly treated obstructions by cauterizing through the lacrimal bone into the nose, effectively creating a fistula between lacrimal sac and nasal cavity. In the 18th century, Woolhouse performed developed an approach aimed to remove the lacrimal sac, create a passage through the lacrimal bone, and place a drain made of metal to enable tear outflow.[18] In part, Wool benefited from improved anatomical knowledge of the nasolacrimal system laid forth by Antoine Maître-Jan, who recognized that the lacrimal sac and ducts were not secretory glands but rather conduits.[19]

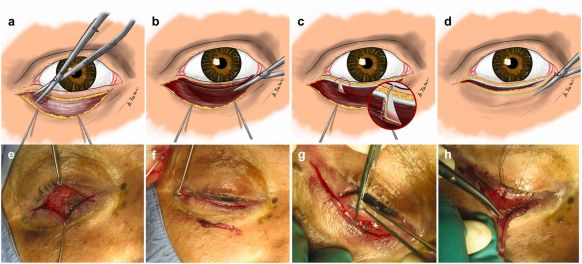

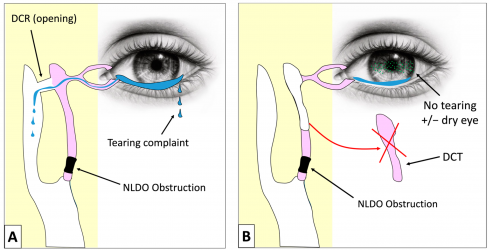

The external dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) (Figure 4) widely used today has its origins in Addeo Toti’s 1904 description of accessing the lacrimal sac through a skin incision and removing its medial wall along with adjacent bone to create a new drainage opening into the nasal cavity, a concept later refined by others to improve healing and success. Early in the 20th century, surgeons such as Kuhnt introduced mucosal flap suturing to limit granulation, while Dupuy-Dutemps and Bourguet developed a flap-based anastomosis between the lacrimal sac and nasal mucosa, eventually reporting high long-term success with further modifications including repeated probing of the lower punctum to minimize scarring.[20]

The late 20th century saw revival and modernization of earlier intranasal approaches. After initial endonasal attempts in 1893 by Caldwell, and later West, practical limitations such as poor visualization inside the nasal cavity delayed progress until rigid nasal endoscopes enabled modern endonasal DCR, first clearly described by McDonogh and Meiring in 1989. With ongoing improvements in visualization and instrumentation, endonasal DCR is now considered comparable in efficacy to external techniques while avoiding a cutaneous scar, and has gained widespread acceptance as an alternative route for treating nasolacrimal duct obstruction.[20]

Orbital Implants

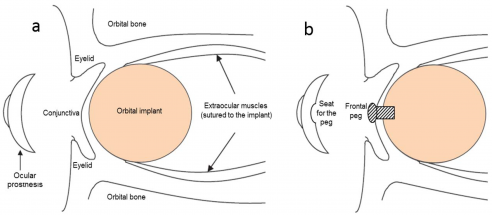

Enucleation involves the complete removal of the globe while preserving the extraocular muscles. On the other hand, evisceration entails removal of the intraocular contents, including the cornea, while leaving the scleral shell and extraocular muscles intact.[21] George Bartisch was credited with the first documented eye removal in 1583.[22] By the early 19th century, the first recorded evisceration was done by James Beer in 1817, when intra-ocular contents were evacuated after an expulsive hemorrhage. In parallel, an early form of enucleation (complete globe removal) evolved such that extraocular muscles, Tenon’s capsule and orbital soft-tissue were preserved to facilitate later socket reconstruction.[23]

However, after globe removal, patients were often left with empty sockets. The first orbital implant, which involved a simple glass sphere, was inserted in 1884 after evisceration by P.H. Mules, marking the start of what would become a century-long search for the ideal orbital volume replacement.

Over subsequent decades, a wide variety of materials were tried, including various metals, cartilage, bone, fat, and rubber.[23] Starting in the 1980s, porous materials (notably, hydroxyapatite derived from coral) became more common, enabling fibrovascular ingrowth, better implant integration, lower extrusion risk, and improved coupling for prosthetic motility.[24] In modern practice, implant selection is individualized based on patient specific factors such as previous surgeries and long-term prosthetic goals,[25] with most orbital implants placed beneath the conjunctiva, creating a barrier from the external environment and reducing the risk of postoperative colonization and infection (Figure 5).[26]

Orbital Decompression

The first documented case of orbital decompression was for Graves’ disease in 1911. Over the next several decades, surgeons systematically tested access through each orbital wall: removal of the orbital roof via a transcranial approach was described in 1931 (Naffziger), medial wall decompression in 1936, orbital floor removal in 1930, and by 1957, the combined medial wall and floor decompression had been introduced. This two-wall technique became the most widely adopted standard. During this period, multiple routes to the bony orbit were developed, including transcutaneous, transconjunctival, transantral, transcranial, and transnasal approaches, and decompression gradually evolved into a staged, multi-wall strategy tailored to disease severity.

In the late 20th century, surgeons introduced three-wall orbital expansion for severe proptosis and later developed the concept of balanced decompression, in which the medial and lateral walls are symmetrically decompressed while preserving the orbital floor to reduce muscle imbalance. Advances in endoscopic sinus surgery have also facilitated minimally invasive decompression of the medial wall and floor. Improved understanding of the subtypes of thyroid eye disease (fat-predominant versus muscle-predominant) led to better patient selection and the development of fat-removal decompression, first proposed in the 1970s and later validated by clinical series, establishing fat excision as an effective option in appropriately selected patients.[1]

Imaging

Advances in orbital imaging have fundamentally transformed the diagnosis and management of orbital disease. The introduction of ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) rendered older techniques such as plain radiography, hypocycloidal polytomography, arteriography, and venography largely obsolete. The clinical utility of ophthalmic ultrasound was first demonstrated in 1956 by Mundt and Hughes, with orbital applications developed in the 1960s by investigators in the United States and Austria. The introduction of the first commercially available B-scan ultrasound system in the early 1970s established ultrasonography as a safe, practical, and cost-effective diagnostic tool that remains valuable despite subsequent advances in cross-sectional imaging.[1]

CT represented the most transformative leap in diagnostic radiology, profoundly influencing clinical medicine and earning the 1979 Nobel Prize in Medicine for its developers. The mathematical foundations were established by Allan MacLeod Cormack, and practical implementation was achieved by Godfrey Newbold Hounsfield in the early 1970s. MRI entered clinical practice in the early 1980s and rapidly became central to the evaluation of orbital and neuro-ophthalmic disease. Ongoing refinements in imaging sequences and surface coil technology have enabled increasingly detailed, in vivo visualization of orbital anatomy, further refining diagnostic accuracy and guiding modern surgical management.[1]

Academic and Professional Organizations

The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) originated from the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology, founded in 1896 to advance education in eye and ear surgery, and became an independent organization in 1979, helping formalize ophthalmology as a modern academic and clinical discipline.[27] As oculoplastics matured into a distinct subspecialty, particularly after the reconstructive demands of the World Wars, the need for focused professional organizations became clear. This led to the founding of the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (ASOPRS) in 1969, created to establish standards of training, research, and clinical excellence in eyelid, lacrimal, and orbital surgery.[28][29][30] Similar organizations subsequently developed internationally, including the European Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, promoting education and collaboration across borders and solidifying oculoplastics as a recognized global subspecialty.[30]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Patel BCK, Anderson RL. History of Oculoplastic Surgery (1896–1996). Ophthalmology. 1996;103:S74-S95. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30766-5

- ↑ Andrade A, Freitas R. Correcting historical errors in lower eyelid reconstruction. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica. 1 AD;32(4):594-598. doi:10.5935/2177-1235.2017RBCP0096

- ↑ Hishmi AM, Koch KR, Matthaei M, Bölke E, Cursiefen C, Heindl LM. Modified Hughes procedure for reconstruction of large full-thickness lower eyelid defects following tumor resection. Eur J Med Res. 2016;21:27. doi:10.1186/s40001-016-0221-1

- ↑ Somenek M. Eyelid defect reconstruction. par. 2022;9(0):N/A-N/A. doi:10.20517/2347-9264.2021.84

- ↑ Ahmad J, Mathes DW, Itani KM. Reconstruction of the Eyelids after Mohs Surgery. Semin Plast Surg. 2008;22(4):306-318. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1095889

- ↑ Yan Y, Fu R, Ji Q, et al. Surgical Strategies for Eyelid Defect Reconstruction: A Review on Principles and Techniques. Ophthalmol Ther. 2022;11(4):1383-1408. doi:10.1007/s40123-022-00533-8

- ↑ Guo Y, Gao T, Lin M, et al. Posterior lamella substitutes in full-thickness eyelid reconstruction: a narrative review. Frontiers of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine. 2023;5(0). doi:10.21037/fomm-21-80

- ↑ Perkins SW, Prischmann J. The Art of Blepharoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2011;27(1):58-66. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1270425

- ↑ DE BLASKOVICS L. TREATMENT OF PTOSIS: THE FORMATION OF A FOLD IN THE EYELID AND RESECTION OF THE LEVATOR AND TARSUS. Arch Ophthalmol. 1929;1(6):672-680. doi:10.1001/archopht.1929.00810010698002

- ↑ CORDES FC, FRITSCHI U. DICKEY OPERATION FOR PTOSIS: RESULTS IN TWENTY-ONE PATIENTS AND THIRTY LIDS. Arch Ophthalmol. 1944;31(6):461-468. doi:10.1001/archopht.1944.00890060031002

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 GIFFORD SR, PUNTENNEY I. MODIFICATION OF THE DICKEY OPERATION FOR PTOSIS. Arch Ophthalmol. 1942;28(5):814-820. doi:10.1001/archopht.1942.00880110062005

- ↑ Jones LT, Quickert MH, Wobig JL. The Cure of Ptosis by Aponeurotic Repair. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93(8):629-634. doi:10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020601008

- ↑ Patel V, Malhotra R. Transconjunctival Blepharoptosis Surgery: A Review of Posterior Approach Ptosis Surgery and Posterior Approach White-Line Advancement. Open Ophthalmol J. 2010;4:81-84. doi:10.2174/1874364101004010081

- ↑ Oh LJ, Wong E, Bae S, Tsirbas A. Closed Posterior Levator Advancement in Severe Ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(5):e1781. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001781

- ↑ Khooshabeh R, Baldwin HC. Isolated Muller’s muscle resection for the correction of blepharoptosis. Eye (Lond). 2008;22(2):267-272. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702605

- ↑ Rubino C, Trignano E, Dore S, et al. 3-Step combined technique for correction of involutional lower eyelid entropion: A case series. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2025;107:162-168. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2025.06.034

- ↑ Mackenzie W. Case of intense and long-continued Photophobia and Blepharospasm, relieved by the Inhalation of Chloroform. Med Chir Trans. 1857;40:175-8. doi: 10.1177/095952875704000114.

- ↑ Yakopson VS, Flanagan JC, Ahn D, Luo BP. Dacryocystorhinostomy: History, evolution and future directions. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2011;25(1):37-49. doi:10.1016/j.sjopt.2010.10.012

- ↑ GUY L. SIMPLE DACRYOCYSTORHINOSTOMY. Arch Ophthalmol. 1938;20(6):954-957. doi:10.1001/archopht.1938.00850240068003

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ullrich K, Malhotra R, Patel BC. Dacryocystorhinostomy. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed November 30, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557851/

- ↑ Eye Removal Surgery: Enucleation and Evisceration. American Academy of Ophthalmology. November 20, 2019. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/treatments/eye-removal-surgery-enucleation-evisceration

- ↑ Jordan DR, Klapper SR. Enucleation and Evisceration. In: Yen MT, ed. Surgery of the Eyelid, Lacrimal System, and Orbit. Oxford University Press; 2011:0. doi:10.1093/oso/9780195340211.003.0029

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Morton A. Chapter 23 ENUCLEATION and EVISCERATION. https://medcoeckapwstorprd01.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/pfw-images/borden/ophthalmic/OPHch23.pdf

- ↑ American Society of Ocularists - Surgical Procedures. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.ocularist.org/resources_surgical_procedures.asp

- ↑ Chen XY, Yang X, Fan XL. The Evolution of Orbital Implants and Current Breakthroughs in Material Design, Selection, Characterization, and Clinical Use. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;9. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.800998

- ↑ Salerno M, Reverberi AP, Baino F. Nanoscale Topographical Characterization of Orbital Implant Materials. Materials. 2018;11(5):660. doi:10.3390/ma11050660

- ↑ Academy’s History - American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed December 7, 2025. https://www.aao.org/about/history

- ↑ DR. VIRGINIA LUBKIN: An Oculoplastic Surgeon for all Seasons. Accessed December 7, 2025. https://www.asoprsfoundation.org/index.php?option=com_dailyplanetblog&view=entry&year=2025&month=02&day=25&id=33:dr-virginia-lubkin-an-oculoplastic-surgeon-for-all-seasons

- ↑ American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (ASOPRS) | National Eye Institute. Accessed December 7, 2025. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/eye-health-organizations-database/american-society-ophthalmic-plastic-and-reconstructive-surgery-asoprs

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 The Society. SBCPO. Accessed December 7, 2025. https://en.sbcpo.org.br/the-society/