Methamphetamine-Induced Keratitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Methamphetamine (MA) is a potent neurostimulant classified as a Schedule II controlled substance in the United States.[1] While it can be utilized in psychiatry for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy, it is more commonly abused as a recreational drug, as it leads to elevated mood, alertness and energy.[2][3]

First identified by Poulsen et al. in 1996, methamphetamine-induced keratitis (MIK) is an important side effect of MA.[4] Given the rise in MA abuse over the past two decades and its potentially devastating impact on vision, eye care providers must be knowledgeable about the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of MIK.

Epidemiology

MIK is a possible side effect of MA use and has been described in several case reports since the 1990s. MA is currently the most common illicit drug according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.[5] In 1998, the prevalence of MA use in the United States was approximately 2.1%, and this has steadily increased since then.[6] The amount of MA seized worldwide quadrupled between 2013 and 2022.[5]

The primary age group of MA abusers ranges from 15 and 64 years old. Psychiatric disorders, peer influence or pressure, curiosity and adventurous tendency have been identified as significant risk factors for initiation of MA.[7][8] Methamphetamine can be consumed orally, through intravenous injection, smoked, or inhaled/snorted.[3]

General Pathology

Methamphetamine use can result in corneal toxicity, leading to MIK. Patients often present with vision loss from corneal ulcers, which in most reported cases are associated with superimposed infectious keratitis. This overlap makes it difficult to determine whether corneal damage is primarily attributable to MIK itself or to infection. Compared to typical infectious keratitis, however, MIK tends to demonstrate more pronounced neurotrophic features.

The corneal ulcers in MIK are often advanced, characterized by large infiltrates, stromal necrosis, and severe thinning. In many cases, rapid corneal melting and perforation can occur despite aggressive topical treatment with fortified antibiotics, necessitating interventions like glue or therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty.

Histopathologic examination of excised corneas in severe MIK may show epithelial loss, varying degrees of stromal inflammation, tissue necrosis, descemetocele formation, and evidence of mixed microbial organisms.[4][9][10][11]

Pathophysiology

Methamphetamine-induced keratitis is thought to result from multiple contributing mechanisms. Poulsen et al first proposed a classification of these causes, and subsequent studies have introduced additional hypotheses regarding its pathophysiology:[9][12][10][13][14]

- Direct pharmacologic and physical effects of MA

- MA acts as a vasoconstrictor, potentially leading to vasculitis and reduced ocular perfusion.

- A heightened pain threshold can impair the blink reflex, increasing the risk of corneal epithelial injury.

- Dopamine and serotonin dysregulation associated with MA use can lead to corneal nerve damage and neurotrophic keratitis.

- Toxic effects of diluting agents and by-products (ex: lidocaine, procaine, quinine, bicarbonate, strychnine, etc.)

- These agents can lead to alkaline burns and ulceration of corneal tissue.

- Manufacturing by-products or contaminants can lead to inadvertent caustic exposure.

- Effects related to the route of drug administration (intravenous, inhalation, smoking)

- Smoking can lead to chemical or thermal burns and tissue damage.

- MA is often sold as a hydrochloride salt, which may cause corneal damage from direct contact or exposure to fumes.

- Hand to eye exposure can also exacerbate corneal injury.

- Psychological, mental, and behavioral effects of MA use

- The hyperactivity and obsessive behaviors induced by MA can result in repetitive eye rubbing or scratching, exacerbating ocular damage.

- Excessive preoccupation with MA use and resulting cognitive deficits can lead to poor ocular hygiene.

Primary Prevention

Because MIK can be vision-threatening, prevention should focus first on discouraging methamphetamine use through community education and outreach. For those actively using MA, harm-reduction strategies—such as promoting proper hand and dental hygiene and minimizing eye rubbing—may help lower the risk of corneal injury.

Diagnosis

MIK is largely a clinical diagnosis. A diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced keratitis should include a detailed history and a complete ophthalmic examination.

History

When evaluating a patient with suspected methamphetamine-induced keratitis, a thorough history is essential. The most critical element is a detailed substance use history, which should include the frequency and route of methamphetamine use.

Clinicians should also inquire about symptom onset, prior ocular trauma, and behaviors that increase keratitis risk. Contact lens use warrants particular attention, including lens type, duration of wear, hygiene practices, as poor lens care can compound infection risk. A complete ocular history should include prior episodes of similar symptoms, previous bacterial or viral keratitis, and any history of eye surgery, including laser refractive procedures.

Review of medications, eye drops, allergies, and relevant family history is also important. Given the rising use of biologics for conditions ranging from atopic dermatitis to malignancy, ophthalmologists must remain vigilant for ocular side effects such as severe keratoconjunctivitis.

Finally, because methamphetamine use carries serious systemic consequences—including multisystem damage, recurrent respiratory illness, seizures, and dental or nail decay—a comprehensive review of systems should be performed.

Symptoms

- Decreased vision

- Foreign body sensation

- Redness

- Ocular pain or decreased sensation

- Tearing

- Itching

- Photophobia

Physical Examination

Examination should include an assessment of visual acuity, intraocular pressure, pupil reaction, and corneal sensation, as neurotrophic keratopathy is a common complication of MA use.

A thorough slit-lamp examination should include assessment of eyelid closure, lashes, and the nasolacrimal system in order to identify risk factors for infection. Corneal infiltrate location, shape, dimensions, and characteristics should be examined with and without fluorescein. Presence of cells, flare, fibrin, or hypopyon within the anterior chamber should be noted.

A dilated fundus exam is esssential to rule out posterior pole involvement, as MA use has been reported to cause retinal vascular occlusion, vasculitis, crystalline retinopathy and non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.[15][16][17][18][19] If visualization of the posterior pole is not possible, B-scan ultrasonography should be performed to rule out additional posterior segment pathology, such as vitritis or endophthalmitis. A thorough examination of both eyes is necessary.

Signs

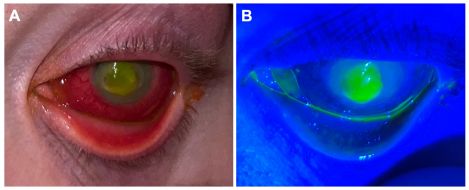

When MIK is mild/moderate (Figure 2), slit lamp examination may reveal:

- Eyelid edema

- Clear or purulent discharge

- Conjunctival injection

- Absence of corneal sensation

- Corneal epithelial defect

- Corneal stromal infiltrate

- Hypopyon

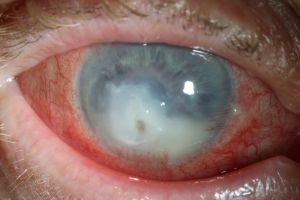

In advanced stage (Figures 3 and 4), clinicians should document these findings:

- Stromal necrosis

- Corneal thinning

- Descemetocele

- Perforation

- Vitritis/endophthalmitis

It is important to note that the clinical findings of MIK often overlap with those of infectious keratitis, as the two frequently coexist.

Clinical Diagnosis

A diagnosis is based largely on examination findings in conjunction with a history of methamphetamine use. Anterior segment optical coherence topography (AS-OCT) can be used to evaluate the extent of corneal thinning.

Laboratory test

A urine toxicology screen can help confirm substance use. Corneal scraping and culture should be performed promptly to guide management. Samples should be assessed for bacteria, fungi, HSV/VZV and acanthemoeba. In select cases, cultures obtained from fingernail swabs may also assist in identifying pathogens and informing antibiotic selection.

When the clinical presentation raises concern for an immune-mediated keratitis, a laboratory workup should be considered to exclude systemic autoimmune disease. Relevant studies may include CBC, CMP, urinalysis, rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP), antinuclear antibody (ANA), and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Potential masquerade conditions such as syphilis, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis should also be ruled out with appropriate serologic and laboratory testing.

Differential diagnosis

- Infectious keratitis

- Neurotrophic keratopathy

- Exposure keratopathy

- Topical anesthetic abuse keratopathy

- Immune-mediated keratitis

- Medication-induced keratitis (in particular biologics)

- Vitamin A deficiency

Management

General treatment

Topical antibiotics should be initiated promptly. Patients need close follow up and should be strictly advised to avoid eye rubbing. Compliance with frequent eye drop administration should be assessed, if support is needed for antibiotic drop administration, inpatient admission can be considered.

Medical therapy

Antibiotic coverage and frequency are guided by the size and severity of corneal damage. In cases of severe keratitis characterized by an infiltrate larger than 1.5mm or located within the visual axis, hourly broad spectrum antibiotics such as fortified vancomycin and fortified tobramycin should be initiated. For moderate cases, a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone drop such as moxifloxacin can be used hourly. For mild cases, treatment may begin with topical fluoroquinolone or polymyxin B/trimethoprim drops every 2 to 4 hours. Definitive management requires adjusting antibiotic therapy according to culture and sensitivity results.

Healing may be prolonged, and re-epithelialization can be challenging in the setting of decreased corneal sensation. Topical steroids can be cautiously considered when the infection is properly controlled and after ruling out atypical pathogens such as fungus or acanthamoeba. Topical steroids can reduce inflammation and prevent complications like synechiae. Careful monitoring is essential to ensure patient safety during this phase of treatment.

Oral vitamin C and tetracyclines may be prescribed to help reduce collagenolysis and slow keratolysis. In cases of corneal thinning, the eye should be protected with a shield. A pressure patch should not be placed.

Medical follow up

Daily follow up is required initially. As above, antibiotic coverage should be adjusted based on sensitivities and clinical response.

Surgery

If corneal perforation occurs or there is descemetocele formation with impending perforation, immediate intervention is critical. For a small defect, cyanoacrylate tissue glue and a bandage contact lens may be adequate. For larger defects, a patch graft or therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty may be necessary to restore the globe integrity and prevent endophthalmitis. If surgery is performed, the corneal specimen can be sent for histopathologic evaluation.

Surgical follow up

Close postoperative follow up is warranted.

Prognosis

Due to the complexity of keratitis and the presence of behavorial/psychological co-morbidities, the prognosis is often guarded. Close follow-up and multi-disciplinary approaches are essential to prevent complications and improve final outcomes.

References

- ↑ Cisneros IE, Ghorpade A. Methamphetamine and HIV-1-induced neurotoxicity: role of trace amine associated receptor 1 cAMP signaling in astrocytes. Neuropharmacology. 2014 Oct;85:499-507.

- ↑ Radfar SR, Rawson RA. Current research on methamphetamine: epidemiology, medical and psychiatric effects, treatment, and harm reduction efforts. Addict Health. 2014 Summer-Autumn;6(3-4):146-54.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Yasaei, R., & Saadabadi, A. (2023). Methamphetamine. In StatPearls [internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Poulsen, Eric J. M.D.; Mannis, Mark J. M.D.; Chang, Steven D. M.D.. Keratitis in Methamphetamine Abusers. Cornea 15(5):p 477-482, September 1996.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 UNODC, World Drug Report 2024. United Nations publication, 2024.

- ↑ Anglin MD, Burke C, Perrochet B, Stamper E, Dawud-Noursi S. History of the methamphetamine problem. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000 Apr-Jun;32(2):137-41.

- ↑ Obadeji A, Kumolalo BF, Oluwole LO, et al. Substance use among adolescent high school students in Nigeria and its relationship with psychosocial factors. J Res Health Sci. 2020;20(2):e00480.

- ↑ WHO. Mental health of adolescents. WHO, 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Franco J, Bennett A, Patel P, Waldrop W, McCulley J. Methamphetamine-Induced Keratitis Case Series. Cornea. 2022;41(3):367-369.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kroll M, Affeldt JC, Meallet M. Methamphetamine keratitis as a variant of neurotrophic ocular surface disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:103

- ↑ Chuck RS, Williams JM, Goldberg MA, Lubniewski AJ. Recurrent corneal ulcerations associated with smokeable methamphetamine abuse. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996 May;121(5):571-2.

- ↑ Fowler AH, Majithia V. Ultimate mimicry: methamphetamine-induced pseudovasculitis. Am J Med. 2015;128:364–366.

- ↑ Movahedan A, Genereux BM, Darvish-Zargar M, et al. Long-term management of severe ocular surface injury due to methamphetamine production accidents. Cornea. 2015;34:433–437.

- ↑ Huang Y, Nguyen NV, Mammo DA, Albini TA, Hayek BR, Timperley BD, Krueger RR, Yeh S. Vision health perspectives on Breaking Bad: Ophthalmic sequelae of methamphetamine use disorder. Front Toxicol. 2023 Mar 8;5:1135792.

- ↑ Shaw H. E., Jr., Lawson J. G., Stulting R. D. (1985). Amaurosis fugax and retinal vasculitis associated with methamphetamine inhalation. J. Clin. Neuroophthalmol. 5 (3), 169–176.

- ↑ Wallace R. T., Brown G. C., Benson W., Sivalingham A. (1992). Sudden retinal manifestations of intranasal cocaine and methamphetamine abuse. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 114 (2), 158–160.

- ↑ Hazin R., Cadet J. L., Kahook M. Y., Saed D. (2009). Ocular manifestations of crystal methamphetamine use. Neurotox. Res. 15 (2), 187–191.

- ↑ Guo J., Tang W., Liu W., Zhang Y., Wang L., Wang W. (2019). Bilateral methamphetamine-induced ischemic retinopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 15, 100473.

- ↑ Wijaya J., Salu P., Leblanc A., Bervoets S. (1999). Acute unilateral visual loss due to a single intranasal methamphetamine abuse. Bull. Soc. Belge. Ophtalmol. 271, 19–25.