Necrotizing Fasciitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Disease

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF), although relatively uncommon, was first recognized by Hippocrates in the fifth century BC. [1] This disease is a severe infection characterized by a rapid and devasting progression involving the superficial fascia leading to skin necrosis. NF commonly affects the abdomen, extremities and perineum. It is associated with a high mortality rate of 25 – 30%.[2] NF has many names including: hospital gangrene, necrotizing erysipelas, flesh eating bacterial infection, and progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene. Periorbital NF, albeit uncommon due to its relatively uncompromised and robust blood supply, has a reported mortality of 8-15% and a rate of vision loss of 13.8%.[1][3]

Etiology

The incidence of NF in general is 3 per 100,000 with 10,000 new cases annually in the US.[4] In a 2-year British prospective study, the incidence of periorbital NF was reported to be 0.24 per million per annum.[5] Periorbital NF is rare in adults and even more so in children as the mean age of diagnosis reported by Lazzeri et al is 50.18 years.[6][7] While some publications have suggested a female predominance (of 54%) others have suggested nearly equal incidence amongst the sexes.[1][2] [7]

Risk Factors

Common triggers for periorbital NF include trauma and surgery. Amrith et al reported unidentifiable triggers in approximately 27% of cases.[1]Known risk factors for the development of periorbital NF include: advanced age, chronic renal failure, peripheral vascular disease, drug abuse, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, rheumatologic disease, systemic malignancy and immunosuppression.[7] The incidence of NF increases with use of immunomodulating agents such as steroids and chemotherapeutic agents.

Etiology

NF can be categorized by the causative microorganisms cultured from the wounds: Type 1 is a polymicrobial infection, primarily affecting immunocompromised individuals, consisting of mixed anaerobes, gram-negative bacilli and enterococci. Type 2 NF consists of infections with group A Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes) with or without a coexisting Staphylococcal infection.[7] The rate of mortality for Type 1 and Type 2 are 20% and 30-35% respectively.[8] The British Ophthalmology Surveillance Unit 2-year prospective study described a mortality rate of 10%.[5] In addition, NF with cervical involvement demonstrated a mortality rate of 20%.[8] Mortality rate increases for NF that involves the lower part of the face and cervical area, areas closer to the mediastinum, chest and carotid sheath which may result in pulmonary complications.[7]

Clinical Course and Features

NF is characterized by the acute onset of a painful non-specific erythematous rash with edema around the affected region. Early on the presentation may resemble erysipelas or preseptal cellulitis. There is fever and severe pain as the infection spreads subcutaneously along the fascial planes.[7] Patients may present with tachycardia disproportionate to the fever. Ocular involvement initially may be limited to keratitis, uveitis, or chorioretinitis. Within 48 hours, the lid skin develops a violaceous discoloration which may progress to the appearance of fluid-filled bullae.[7] Thrombosis of dermal and subdermal perforating vessels lead to black necrotic patches. Within 4-5 days, frank cutaneous gangrene develops; within 8-10 days the skin sloughs and becomes gangrenous due to underlying suppuration.[7]

NF behaves differently in the orbit relative to other regions of the body. The orbit has a rich vascular supply, thin eyelid skin and lack of subcutaneous fat between the skin and the muscle[9], as such the skin infection becomes noticeable earlier and the necrosis of the thin eyelids occurs rapidly – thus, the symptoms to treatment are typically shorter.[7] The marginal lid is often spared because its extensive blood supply from marginal arterial arcade.

Differential Diagnosis of Necrotizing Fasciitis

Early necrotizing fasciitis (NF) of the periorbital region can present similarly to other acute orbital processes. Because timely recognition and appropriate management is critical to recovery and residual comorbidities, it is necessary to consider other differential diagnosis.[10][11] Among these, Sweet Syndrome (SS) -particularly its necrotizing variant (nSS)-warrants special attention due to its striking clinical similarity to NF and the very different management it requires.

Orbital Cellulitis

- Signs and Symptoms: fever, proptosis, erythematous swollen lids, painful or restricted extraocular movements.

- Key distinction from necrotizing fasciitis: responds to antibiotics without need for debridement; lacks skin necrosis or gas formation (crepitus of tissue).[12]

- Most present with concomitant sinus disease.

Preseptal (Periorbital) Cellulitis

- Signs and Symptoms: lid erythema, edema, tenderness confined anterior to the septum; no proptosis or developing ophthalmoplegia.

- Key distinction: superficial infection, no fascial involvement; improves with antibiotics (often oral outpatient course, occasionally inpatient intravenous administration). [13]

Erysipelas

- Signs and Symptoms: sharply demarcated, bright red, raised patches ± fever.

- Key distinction: superficial dermal infection; lacks bullae, necrosis, or deep fascial spread.[14]

- Most commonly involved organism is S. pyogenes.

Rhino-Orbital Mucormycosis

- Presents in immunocompromised and poorly controlled diabetics.

- Signs and Symptoms: Sinusitis, facial pain, developing ophthalmoplegia, black necrotic eschar on nasal turbinates or palate.

- Key distinction: angioinvasive fungal infection; Histopathologic review shows broad based, pauci-septate to aseptate, right angle hyphae. Requires anti-fungal therapy and surgical debridement. [15][16]

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (previously referred to as Wegener’s)

- Signs and Symptoms: orbital pain, proptosis, diplopia, lacrimal gland enlargement; often with invovleemt of the face/nose (sinusitis), lung, and kidneys.

- Key distinction: chronic autoimmune vasculitis; confirmed with biopsy and c-ANCA; no acute necrosis or gas. [17]

- Histopathologic attributes: Necrotizing granuloma(s) with central necrosis, palisading histiocytes, areas of storiform fibrosis, myxoid degeneration, focal aggregates of eosinophils, and must have present vasculitis.

Sarcoidosis (Orbital involvement)

- Signs and Symptoms:: painless eyelid swelling, proptosis, diplopia.

- Key distinction: gradual onset, non-infectious; biopsy shows non-caseating granulomas. [18]

Orbital Neoplasms (e.g., rhabdomyosarcoma, leukemia, metastasis)

- Signs and Symptoms:: subacute proptosis, eyelid ecchymosis (“raccoon eyes”), or a non-resolving, progressive orbital mass.

- Key distinction: no fever, necrosis, or gas; imaging reveals a mass lesion. [19]

Orbital Trauma

- Signs and Symptoms:: acute proptosis, rock-hard swollen lids, decreased vision after trauma (hemorrhage); lid crepitus after nose blowing (emphysema).

- Key distinction: trauma-related, not infectious; managed with decompression or observation. [20]

Warfarin-Induced Skin Necrosis

- Signs and Symptoms:: painful purpuric patches 3-6 days after warfarin initiation → hemorrhagic blisters → black eschars.

- Key distinction: thrombotic, not infectious; no gas or systemic sepsis; treated by reversing anticoagulation. [21]

Sweet Syndrome (Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis)

- Signs and Symptoms:: painful erythematous periocular plaques with systemic fever.

- Key distinction: sterile neutrophilic infiltrate on biopsy; negative cultures; rapid response to corticosteroids. Rare periocular cases can closely mimic NF. [22]

Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome

Disease Entity

Rare case reports have documented that patients who were initially diagnosed with Necrotizing Fasciitis (NF) continued to decompensate following treatment with surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy.

One case report documents three immunocompromised patients who presented with evidence of NF. Despite all three patients receiving several rounds of antibiotic therapy and two patients undergoing significant surgical debridement, these patients appeared septic and demonstrated pathergy. Histopathological samples were obtained from each patient, which revealed marked necrosis of the soft tissue, including myonecrosis in the two patients who underwent debridement. All three patients demonstrated rapid response to high-dose systemic corticosteroids. [23]

A second case report describes two patients, one with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and one with relapsed and refractory acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), who presented with signs of NF on the upper eyelids.

- The MDS patient failed 5 days of systemic antibiotics and underwent incision and drainage of a left upper eyelid abscess. Following I&D, her wound appeared violaceous with necrotic-appearing crust. Necrosis continued spreading periorbitally even with systemic antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals in the regimen. She was taken to the OR for debridement, after which she still showed signs of tissue necrosis progression. In a second round of debridement, an intra-operative pathological sample was obtained, which revealed a dense dermal neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate without microorganisms.

- The AML patient presented with right upper eyelid pain, swelling, and redness. Biopsy and culture revealed HSV-1 and coagulase-negative streptococci. Despite initiation of acyclovir and systemic antibiotics, her lesions became necrotic with eschar development, including her venipuncture sites. Following dermatology consult, biopsies of the lesions were taken, revealing dermal neutrophilic infiltrates with areas of necrosis any evidence of microorganisms. Following initiation of IV corticosteroids, her eschars sloughed off, and she showed signs of clinical improvement. [22]

Similarities and Differences between Sweet Syndrome and Necrotizing Fasciitis

Sweet Syndrome, also referred to as Acute Febrile Neutrophilic Dermatosis, is an autoinflammatory disorder that, while primarily dermatological, does have ocular manifestations; the most common of which is conjunctivitis. However, it can have variable presentation and affect various structures of the eye. Like Necrotizing Fasciitis, SS presents abruptly with a painful, progressive, erythematous, and edematous rash and can mimic cellulitis. Both conditions can develop in the setting of systemic malignancy. Sweet Syndrome is defined by neutrophilic invasion of the tissue rather than the bacterial infiltration displayed in NF.

Pathophysiology

While NF is due to microbial infection, often following trauma or surgery, the exact mechanism behind the development of SS has unclear etiology but may be related to a hypersensitivity to the cytokines and neutrophils activated by interleukin-1.

There are three subtypes of SS.

- Classical(idiopathic) SS tends to present in inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, or following an upper respiratory or gastrointestinal infection.

- Malignancy-associated SS most frequently presents in the context of blood cancers (85%), primarily acute myelogenous leukemia.

- Drug-induced SS can follow the use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, TMP-SMX, all trans-retinoic acid proteasome inhibitors, hypomethylating agents, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and lenalidomide.

Management

Management of Necrotizing fasciitis is debridement, whereas debriding in Sweet syndrome can induce pathergy. Due to such similar clinical appearance of the two pathologies, it is important to consider the negative implications of mistaking Sweet Syndrome for Necrotizing Fasciitis. These can include unnecessary tissue removal, continued process spread, acute decompensation, and even death. One should consider taking a tissue biopsy intra-operatively for microbiology evaluation to mitigate the consequences of misdiagnosis and more rapidly begin proper management of SS with systemic corticosteroids.

Of note, in addition to its presentation in Sweet Syndrome, pathergy is also documented in Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PG), which is an additional, yet rare, form of neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by ulcerative lesions. Like SS, PG has associations with inflammatory bowel disease and myelodysplastic syndromes.[24] In contrast to the pathergy ulcers that develop in PG, SS pathergy lesions tend to be tender and erythematous as opposed to ulcerative. [25]

Management of each pathology differs significantly. Whereas definitive treatment for NF is surgical debridement, debriding Sweet Syndrome displays pathergy and can lead to further expansion of the disease. [23]

Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for SS, whereas steroids can predispose an individual to NF. Definitive diagnosis for SS is histopathological diagnosis, while NF diagnosis is through gram stain and culture.

Diagnosis of Necrotizing Fasciitis

Diagnosis still is primarily clinical based on symptoms and disease progression. According to the IDSA guidelines for NF, features that may help differentiate cellulitis from NF are (1) severe pain that seems disproportional to clinical findings; (2) failure to respond to initial antibiotic therapy; (3) hard, wooden feeling of the subcutaneous tissue, extending beyond the area of apparent skin involvement; (4) systemic toxicity; (5) edema or tenderness extending beyond the cutaneous erythema; (6) crepitus; (7) bullous lesions; and (8) skin necrosis or ecchymosis.[26] [27] Diagnosis is confirmed with a deep tissue biopsy with gram stain and culture.[26]

Imaging

While imaging is not necessary to make a diagnosis, CT and MRI do play a role in identifying the extent of the infection and aid in the planning of surgery. CT is the modality of choice because it can offer fast and easy localization of the initial site of infection, extent of disease, presence of gas and fluid-filled bullae and anatomical information.[7] In addition, through CT and MRI imaging – NF can be excluded when no fascial subcutaneous or deeper cutaneous layer involvement is shown.

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) Score uses values of C-Reactive protein, white blood cells, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine, and glucose to help distinguish NF from other soft tissue infections.[28] A LRINEC score of greater than 6 warrants further investigation. High LRINEC scores (>5) can be seen in other musculoskeletal infections. [29]

Management

Treatment

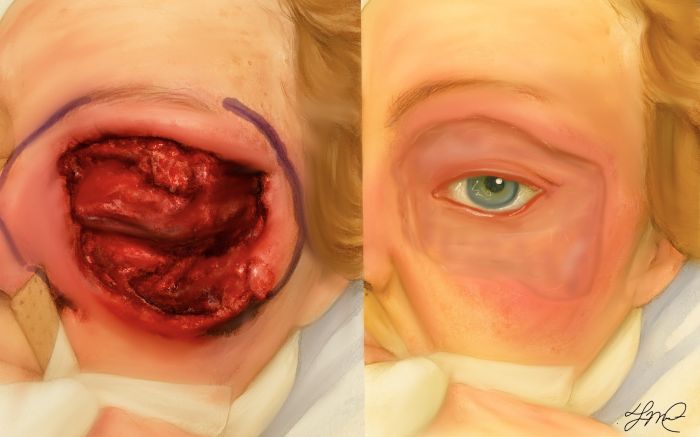

The mainstay of treatment for NF is surgical intervention with serial debridement coupled with aggressive antibiotic therapy, fluid resuscitation, and blood pressure support.[26] Early recognition and initiation of treatment help to decrease morbidity and mortality. There are only a handful of cases of periorbital NF that have successfully been treated with medical intervention alone .[1][3] Antimicrobial coverage includes aerobes (including MRSA), and anaerobes. Combinations may include vancomycin plus one of the following (1) piperacillin-tazobactam, (2) a carbapenem, (3) ceftriaxone plus metronidazole, (4) fluoroquinolone metronidazole. Clindamycin should be added as it suppresses streptococcal toxin and cytokine production.[26]

As mentioned earlier, surgical intervention is the mainstay component of treatment for NF and periorbital NF. In cases of periorbital NF, a computer-tomographic (CT) – guided approach to surgical debridement has been used to minimize the loss of healthy tissue by providing information regarding the extent of disease, confirming the presence/absence of gas, localizing the initial site of infection, and can providing anatomic information to guide surgical debridement.[30] Preserving healthy tissue facilitates later reconstruction.[30]

The efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has not been well established in the treatment of streptococcus toxic shock syndrome and its role in NF. Extracellular streptococcal toxin plays a role in organ failure and tissue necrosis, therefore neutralizing it theoretically would improve patient outcomes. However, because of the batch variability IVIG it is difficult to study effects of this treatment option on outcome.

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy may also play a role in the treatment of NF and orbital NF. HBO therapy has been show to reduce mortality and improve tissue viability. This is likely achieved by HBO therapy’s role in inhibition of exotoxin production, leucocyte function, and attaining sufficient tissue oxygen levels to kill strict anaerobes.[1][7][31] [32] [33] However, the mainstay treatment includes surgical debridement, which should not be delayed to facilitate HBO therapy, and it should be employed cautiously because of it’s own associated morbidity and mortality.

In addition there is increasing evidence of the efficacy of hypochlorous acid irrigation in the treatment of necrotizing facititis. [34]

After the initial infection is controlled and surgical debridement completed, there can be large areas left to heal. Survivors of NF and periorbital NF can have substantial cosmetic and functional defects. Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is currently being employed to facilitate debridement, to promote wound healing and granulation tissue development, and to act as a bridge allowing temporary wound closure. There is some reluctance to adopt this technique for periorbital NF as NPWT may increase intraocular pressure, worsening glaucomatous changes, or could lead to central retinal vein occlusion – causing decreased vision or at worst blindness. A case report of periorbital NF and NPWT demonstrated positive results with preserved visual acuity and a fair cosmetic outcome, suggesting that this may be an appropriate method in some cases.[35]

The key to the successful treatment of NF is early and aggressive diagnosis and treatment.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Amrith, S., Hosdurga Pai, V. & Ling, W. W. Periorbital necrotizing fasciitis - a review. Acta Ophthalmol. (Copenh.) 91, 596–603 (2013).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gelaw, Y. & Abateneh, A. Periocular necrotizing fasciitis following retrobulbar injection. Clin. Ophthalmol. Auckl. NZ 8, 289–292 (2014).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mehta, R., Kumar, A., Crock, C. & McNab, A. Medical management of periorbital necrotising fasciitis. Orbit Amst. Neth. 32, 253–255 (2013).

- ↑ Elner, V. M., Demirci, H., Nerad, J. A. & Hassan, A. S. Periocular Necrotizing Fasciitis with Visual Loss. Ophthalmology 113, 2338–2345 (2006).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Flavahan, P. W., Cauchi, P., Gregory, M. E., Foot, B. & Drummond, S. R. Incidence of periorbital necrotising fasciitis in the UK population: a BOSU study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. bjophthalmol–2013–304735 (2014). doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304735

- ↑ Khurana, S. et al. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis in infants: Presentation and management of six cases. Trop. Doct. 45, 188–193 (2015).

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Lazzeri, D. et al. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 94, 1577–1585 (2010).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Wong, C.-H. et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 85-A, 1454–1460 (2003).

- ↑ Luksich, J. A., Holds, J. B. & Hartstein, M. E. Conservative management of necrotizing fasciitis of the eyelids. Ophthalmology 109, 2118–2122 (2002).

- ↑ Lazzeri D, Lazzeri S, Figus M, Tascini C, Bocci G, Colizzi L, Giannotti G, Lorenzetti F, Gandini D, Danesi R, Menichetti F, Del Tacca M, Nardi M, Pantaloni M. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010 Dec;94(12):1577-85. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.167486. Epub 2009 Nov 5. PMID: 19897473.

- ↑ Paz Maya, S., Dualde Beltrán, D., Lemercier, P., & Leiva-Salinas, C. (2014). Necrotizing fasciitis: an urgent diagnosis. Skeletal radiology, 43(5), 577-589.

- ↑ Pelletier J, Koyfman A, Long B. High risk and low prevalence diseases: Orbital cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2023 Jun;68:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2023.02.024. Epub 2023 Feb 26. PMID: 36893591.

- ↑ Baring, D. E. C., & Hilmi, O. J. (2011). An evidence based review of periorbital cellulitis. Clinical Otolaryngology, 36(1), 57.

- ↑ Hammar H, Wanger L. Erysipelas and necrotizing fasciitis. Br J Dermatol. 1977 Apr;96(4):409-19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1977.tb07137.x. PMID: 324513.

- ↑ Sen, M., Lahane, S., Lahane, T. P., Parekh, R., & Honavar, S. G. (2021). Mucor in a viral land: a tale of two pathogens. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 69(2), 244-252.

- ↑ Wali, U., Balkhair, A., & Al-Mujaini, A. (2012). Cerebro-rhino orbital mucormycosis: an update. Journal of infection and public health, 5(2), 116-126.

- ↑ Kubaisi, B., Samra, K. A., & Foster, C. S. (2016). Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's disease): An updated review of ocular disease manifestations. Intractable & rare diseases research, 5(2), 61-69.

- ↑ Pasadhika, S., & Rosenbaum, J. T. (2015). Ocular sarcoidosis. Clinics in chest medicine, 36(4), 669.

- ↑ Jurdy L, Merks JH, Pieters BR, Mourits MP, Kloos RJ, Strackee SD, Saeed P. Orbital rhabdomyosarcomas: A review. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2013 Jul;27(3):167-75. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.06.004. PMID: 24227982; PMCID: PMC3770217.

- ↑ McCallum, E., Keren, S., Lapira, M., & Norris, J. H. Orbital compartment syndrome: an update with review of the literature. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019; 13: 2189–94.

- ↑ Fraga R, Diniz LM, Lucas EA, Emerich PS. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis in a patient with protein S deficiency. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(4):612-613. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187310

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Vongsachang H, Chiou CA, Azad AD, Lin LY, Yoon MK, Lefebvre DR, Stagner AM. Periorbital necrotizing sweet syndrome: A report of two cases mimicking necrotizing soft tissue infections. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2024 Mar 2;34:102033. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2024.102033. PMID: 38487334; PMCID: PMC10937104.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Kroshinsky D, Alloo A, Rothschild B, et al. Necrotizing Sweet syndrome: a new variant of neutrophilic dermatosis mimicking necrotizing fasciitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):945-954. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.024

- ↑ Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet's syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73(856):65-68. doi:10.1136/pgmj.73.856.65

- ↑ Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):595-602. doi:10.1111/bjd.13955

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Stevens, D. L. et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 59, e10–52 (2014).

- ↑ Anaya, D. A. & Dellinger, E. P. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 44, 705–710 (2007).

- ↑ Wong, C.-H., Khin, L.-W., Heng, K.-S., Tan, K.-C. & Low, C.-O. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit. Care Med. 32, 1535–1541 (2004).

- ↑ Carbonetti, F. et al. The role of contrast enhanced computed tomography in the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis and comparison with the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC). Radiol. Med. (Torino) 121, 106–121 (2015).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Saldana, M., Gupta, D., Khandwala, M., Weir, R. & Beigi, B. Periorbital necrotizing fasciitis: outcomes using a CT-guided surgical debridement approach. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 20, 209–214 (2010).

- ↑ Lazzeri, D. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as further adjunctive therapy in the treatment of periorbital necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A Streptococcus. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 26, 504–505; author reply 505 (2010).

- ↑ Riseman, J. A. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for necrotizing fasciitis reduces mortality and the need for debridements. Surgery 108, 847–850 (1990).

- ↑ Brown, D. R., Davis, N. L., Lepawsky, M., Cunningham, J. & Kortbeek, J. A multicenter review of the treatment of major truncal necrotizing infections with and without hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Am. J. Surg. 167, 485–489 (1994).

- ↑ Crew JR, Thibodeaux KT, Speyrer MS, Gauto AR, Shiau T, Pang L, Bley K, Debabov D. Flow-through Instillation of Hypochlorous Acid in the Treatment of Necrotizing Fasciitis. Wounds. 2016 Feb;28(2):40-7. PMID: 26891136.

- ↑ Semlacher, R. A. et al. Safety of negative-pressure wound therapy over ocular structures. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 28, e98–101 (2012).