Retinal Detachment

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease

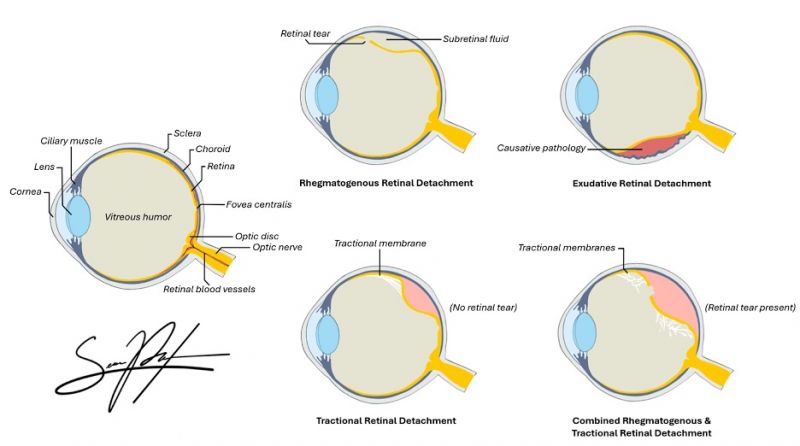

Retinal detachment is a sight-threatening condition with an incidence of approximately 1 in 10000, with higher rates observed in males, myopic eyes, or after ocular surgery (i.e. cataract surgery).[1][2] It occurs when subretinal fluid accumulates between the neurosensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium, resulting in disruption of photoreceptor function and consequential vision loss. Prior to the 1920s, was a permanently blinding condition. In subsequent years, Jules Gonin, MD, pioneered the first retinal detachment repairs in Lausanne, Switzerland.[3] In 1945, after the development of the binocular indirect ophthalmoscope by Charles Schepens, MD, techniques for retinal detachment repair improved. In the last 50 years, techniques in scleral buckling, pneumatic retinopexy, vitrectomy, and panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) have made the repair of retinal detachments significantly more manageable with better visual outcomes.

Types of Retinal Detachment

- Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

- Traction Retinal Detachment

- Exudative (Serous) Retinal Detachment

- Combined Detachment

Key Risk Factors for Retinal Detachment

| Rhegmatogenous | Tractional | Exudative (Serous) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

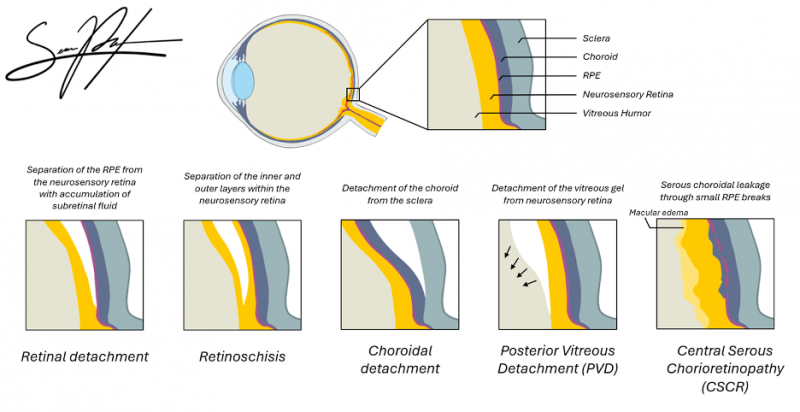

Pathophysiology

The retina is composed of multiple neuronal layers responsible for phototransduction. The outermost layer, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) layer, is essential for maintaining photoreceptor metabolism, adhesion, and fluid transport.[5] Normally, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is able to maintain adhesion with the overlying neurosensory retina through a variety of mechanisms, including the active transport of subretinal fluid across the RPE, metabolic activity of the RPE, and interdigitation of the photoreceptor outer segments and the RPE microvilli. Retinal detachment occurs when subretinal fluid accumulates between the neurosensory retina and the RPE layer, thus overwhelming these adhesive mechanisms and disrupting the retinal interface. Oxygen and nutrient diffusion is then impaired, resulting in rapid photoreceptor degeneration.[5]

Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment (RRD)

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) often follows posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and vitreous syneresis, where a full-thickness break in the retina allows liquified vitreous to flow directly into and accumulate in the subretinal space.[5] RRD is facilitated by age-related vitreous liquefaction, posterior vitreous detachment, and areas of strong vitreoretinal adhesion, such as lattice degeneration or myopic degeneration. Molecular and proteomic studies have identified that RRD is associated with specific changes in the vitreous proteome, including activation of glycolysis, photoreceptor death pathways, and reorganization of cell adhesion molecules.[7] RRDs are also often due to retinal tears from trauma and/or associated with PVD.

Tractional Retinal Detachment (TRD)

In tractional retinal detachment (TRD), proliferative fibrovascular membranes on the surface of the retina or vitreous contract and pull on the neurosensory retina surface, exerting anterior-posterior or tangential traction. The traction caused by these vitreoretinal adhesions results in a physical separation between the neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium.

Common etiologies of TRD include proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), sickle cell retinopathy, and other disease processes leading to neovascularization of the retina (i.e. retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)).[5] TRDs may also be caused by proliferative vitreoretinopathy after ocular trauma or surgery.

Exudative (Serous) Retinal Detachment (ERD)

In exudative (or serous) retinal detachment (ERD or SRD), the retina detaches due to accumulation of subretinal fluid from inflammatory mediators, exudation of fluid from a mass lesion (i.e. choroidal melanoma), insufficient RPE function, or vascular abnormalities (i.e. Coats disease) causing leakage of fluid from the choroid or retinal vessels into the subretinal space.[5] ERDs/SRDs can be caused by a variety of inflammatory or exudative retinal disease processes, such as sarcoidosis, medication toxicity, myeloma, or choroidal neoplasms.[9] ERDs/SRDs may also be the presenting sign in patients with aggressive metastatic cancer, such as testicular cancer.

Combined Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment may present with multiple types simultaneously depending on the primary cause of vision loss. For example, combined traction and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment may occur in chronic proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), as scar tissue can cause traction on the retina to induce a rhegmatogenous tear.[10]

Recurrent Retinal Detachment

Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy (PVR) represents the most common cause of recurrent detachment following surgical repair whether by vitrectomy, scleral buckling, or retinectomy.[11] It involves migration and proliferation of the retinal pigment epithelium and glial cells, leading to membrane formation and tractional re-detachment.[12]

Other causes include insufficient retinopexy (inadequate sealing of retinal breaks), new or missed retinal tears, and complex retinal detachment anatomy, but these are less frequent than PVR.[13][14][15] In some series, insufficient retinopexy is cited as the most common technical cause, but PVR remains the predominant biological cause, especially in complex or delayed cases.

| Rhegmatogenous | Tractional | Exudative (Serous) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | Aphasia, myopia, blunt trauma, photopsia, floaters, visual field defect; progressive, generally healthy | DM, ischemic venous occlusive disease, sickle cell disease, penetrating trauma, prematurity | Systemic factors such as malignant HTN, eclampsia, renal failure, severe CSCR |

| Retinal break | Tears or holes identified in 90% - 95% of cases | None or may develop secondarily | None or coincidental |

| Extent and characteristics of detachment | Extends ora serrata to ONH early, has convex boarders and surfaces, corrugated appearance, gravity dependent | Frequently does not extend to ora serrata, may be central or peripheral, has concave boarders and surfaces | Volume and gravity dependent; extension to ora serrata is variable, may be central or peripheral, smooth surface |

| Retinal mobility | Undulating bullae or folds | Taut retina, peaks to traction points | Smoothly elevated bullae, usually without folds |

| Evidence of chronicity | Demarcation lines, intraretinal macrocysts, atrophic retina | Demarcation lines | Usually none |

| Pigment in vitreous | Present in 70% of cases | Present in trauma cases | Not present |

| Vitreous changes | Frequently syneretic; posterior vitreous detachment, traction on flap of tear | Vitreoretinal traction with preretinal proliferative membranes | Usually clear, except in uveitis |

| Subretinal fluids | Clear | Clear, no shift | May be turbid and shift rapidly to dependent location with changes in head position |

| Choroidal mass | None | None | May be present |

| Intraocular pressure | Frequently low | Usually normal | Varies |

| Transillumination | Normal | Normal | Normal; however, blocked transillumination if pigmented choroidal lesion present |

| Examples of conditions causing detachment | Retinal break | PDR, ROP, sickle cell retinopathy, trauma | Uveitis, metastatic tumor, malignant melanoma, Coats disease, Vogt-Koyanagi-Herada syndrome, retinoblastoma, choroidal hemangioma, senile exudative maculopathy, exudative detachment after cryotherapy or diathermy |

Diagnosis

History

Patients who present with symptoms of new-onset significant photopsias and/or persistent new floaters should be suspected of having a retinal tear, which could lead to a retinal detachment. A patient with constant fixed or slowly progressive visual field loss should be suspected of having a detachment until proven otherwise. A review of systems and complete past medical history should be obtained, including information on the onset of symptoms, presence and duration of decreased central visual acuity, prior trauma, prior surgery, and hemorrhage.

Patients often describe:

- Sudden onset of flashes (photopsias) due to vitreoretinal traction.

- Floaters representing pigment or blood in the vitreous cavity.

- A curtain or shadow over the peripheral or central vision corresponding to detached retinal areas.

- Loss of central vision, signifying detachment of the macula.

Physical Examination

Visual acuity, pupillary examination, visual field testing, and intraocular pressure measurement are important parts of the pre-dilated ophthalmic examination when evaluating patients with symptoms of retinal detachment. Additional examination should include an assessment of color vision in the visual field.

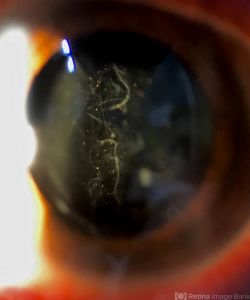

Slit lamp examination of the anterior segment should be completed prior to dilation. Examination of the anterior vitreous for pigment (Schaffer's sign) or vitreous hemorrhage is critical. A thorough fundus examination to include indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression and visualization to the ora serrata should also be completed. A detailed drawing describing the detachment with location of retinal pathology may be documented.

On examination:

- Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) may be present.

- Fundus examination with scleral depression and visualization to the ora serrata: reveals an elevated, mobile, opaque retina with undulating folds.

- Shafer’s sign (“tobacco dust”) — pigment granules in the anterior vitreous that come from the RPE— strongly suggests a retinal break.

- Intraocular pressure (IOP) is often lower in the affected eye.

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment has a characteristic corrugated appearance that undulates with eye movements, differentiating it from a tractional or serous detachment; tractional detachments have smooth concave surfaces with minimal shifting with eye movements, while serous detachments show a smooth retinal surface and shifting fluid depending on patient positioning. In the vast majority of cases, a retinal break will be identified with proper examination, thus confirming a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Without visualization of a retinal break, the diagnosis of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment should be questioned. However, there are cases in which the retinal break is obscured by vitreous hemorrhage or other media opacities, and occasionally the offending retinal breaks are too small to visualize.

If there is no view to the posterior pole, such as in hemorrhage or media opacity, B-scan ultrasound should be used to evaluate the retinal and vitreous status.

| Lincoff Rules for Finding the Break in Primary Rhegmatogenous RD[18][19] |

|---|

|

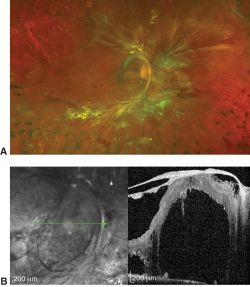

Imaging

Retinal detachment is largely a clinical diagnosis. When available, imaging via OCT and/or wide-field fundus photography may be appropriate when view of the posterior pole is hindered by media opacities or to examine and document the status of the macula.

Indirect Ophthalmoscopy

Indirect ophthalmoscopy remains the gold standard for detection and localization of retinal breaks and detachment extent.[13][20] Thorough examination with scleral depression and visualization to the ora serrata will help ensure proper evaluation of detachment and identify anteriorly located, subtle, and/or peripheral tears.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

OCT provides high-resolution cross-sectional images that confirm neurosensory detachment and differentiate RD from retinoschisis or serous macular detachment. Spectral-domain OCT enables direct visualization of the separation between the neurosensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium in retinal detachment. OCT can help demonstrate splitting within the retinal layers to identify schisis cavities and inner or outer wall breaks in retinoschisis, and distinguish smooth, dome-shaped subretinal fluid without retinal breaks in serous macular detachment.[21][22]

B-scan Ultrasonography

B-scan ultrasonography is essential when media opacity (e.g., vitreous hemorrhage, dense cataract) precludes fundus visualization. It enables assessment of the retina in the presence of vitreous hemorrhage or other media opacity, and is used to diagnose diabetic retinal detachments and define the extent and severity of vitreoretinal traction in these settings.[23] The detached retina appears as a bright, mobile, & echogenic membrane tethered to the optic disc but separated from the choroid, and this appearance on ultrasonography is both highly sensitive and specific for retinal detachment.[24] The membrane’s mobility and folding are best appreciated during kinetic examination, where the patient moves the eye and the detached retina undulates, remaining anchored at the optic nerve head.

Ancillary Testing

Laboratory testing is typically only indicated in tractional or exudative detachments. If a cause for the tractional retinal detachment cannot be determined via the patient's history, further laboratory analysis may be required to determine if diabetes, sickle cell disease, carotid disease, or another systemic or ocular process is the source for proliferative retinopathy. Laboratory investigation and systemic evaluation may be indicated for exudative detachments, as these may be due to systemic, neoplastic, or ocular inflammatory processes. In these cases, fluorescein angiography may be indicated to further clarify exudative processes, such as macular degeneration, central serous chorioretinopathy, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome or other uveitic processes. Ultrasound is a useful imaging modality to evaluate choroidal masses or posterior scleritis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of retinal detachment includes retinoschisis and choroidal mass. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is most often confused with retinoschisis and serous retinal detachment. Retinoschisis can be distinguished from retinal detachment by its appearance on ultrasound: the presence of inner layer dots (Muller footplates), uptake of photocoagulation, and absolute scotoma (vs relative scotoma in retinal detachment). Choroidal masses can be distinguished from retinal detachment by observing the characteristics on ultrasound imaging. Retinal detachments may also be associated with other findings including choroidal detachment and macular hole.[25]

Management

General Principles

Once a retinal detachment has been identified, one must determine what type of detachment is present. The goal of treatment for retinal detachment is anatomic reattachment of the neurosensory retina and restoration of visual function. Management depends on the type and extent of detachment, macular involvement, lens status, and surgeon experience. Surgical management is indicated for rhegmatogenous and tractional detachments.[26][27][28]

Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment (RRD)

For rhegmatogenous detachments, all retinal breaks should be identified, treated, and closed. Techniques for repair include laser retinopexy, pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckle, vitrectomy, or combinations of these techniques:

- Laser Retinopexy: Typically reserved for small, localized detachments or breaks in which laser barricade can be safely performed without interfering with the patient’s visual function while preventing propagation of the detachment. Minimally invasive, clinic setting, lower cost. Limited to the size of tears.

- Pneumatic Retinopexy: Indicated for single or limited superior retinal break(s) (retinal tears in the superior eight clock hours and single breaks of less than one clock hour), cooperative patient, clear media. Procedure involves intravitreal injection of an expansile gas (SF₆ or C₃F₈) bubble to tamponade the break, followed by cryopexy or laser retinopexy. Head positioning to ensure proper tamponade is critical to successful repair. Minimally invasive, clinic setting, lower cost. Limitations include inferior breaks, multiple tears, proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR).

- Scleral Buckle: Silicone bands are permanently placed around the outside of the globe under the extraocular rectus muscles, indenting the sclera externally to support retinal tears and relieve vitreoretinal traction. Performed in the operating room and often combined with retinopexy, i.e. cryotherapy. Indications include young phakic patients, peripheral breaks, absence of significant PVR. Excellent long-term success with experienced surgeons; oldest method of repair of retinal detachment.

- Pars Plana Vitrectomy (PPV): 20-gauge, 23-gauge, 25-gauge, or even 27-gauge instruments used to cut vitreous strands to relieve vitreous traction, drain subretinal fluid, and allows endolaser with internal tamponade (gas or silicone oil) to flatten the retina. Indications include pseudophakia, media opacity, posterior breaks, PVR, giant retinal tears. Advances: Small-gauge vitrectomy, wide-field viewing systems, perfluorocarbon liquids, and chandelier illumination have improved outcomes.

- Combined Procedures: In complex or recurrent cases, a combination of buckle and vitrectomy may be used to address both anterior and posterior traction.

Tractional Retinal Detachment (TRD)

The primary goal is relief of tractional elements (usually epiretinal or subretinal membranes).

- Primary management: PPV with membrane segmentation and delamination; may be combined with scleral buckling as an adjunct.

- Adjuncts: Intraoperative dyes (trypan blue, brilliant blue G) to aid visualization of fibrovascular tissue.

- Timing: Surgery is indicated if the macula is threatened or detached; observation may be appropriate for localized, stable TRDs.

Exudative Retinal Detachment

Any inflammatory disease or underlying mass should be identified and treated, if possible.

- Treatment primarily focuses on underlying cause (e.g.):

- Corticosteroids for inflammatory disease.

- Photodynamic therapy or anti-VEGF for choroidal neovascularization.

- Tumor management (e.g., plaque radiotherapy for choroidal melanoma).

[Dr. Amrit Sahil Panjwani]. Treatment of Retinal Detachment (Video). Available at: https://youtu.be/g4dZksCd_Ik.[29]

Complications

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) is the most common cause of repair failure and occurs in about 8–10% of patients undergoing primary retinal detachment repair.[30][31] Risk factors for PVR include age, giant retinal tears, retinal detachments involving more than 2 quadrants, previous retinal detachment repair, use of cryotherapy, vitreous hemorrhage, choroidal detachment, and trauma.[32] Proliferative vitreoretinopathy requires surgical intervention to release the traction caused by membranes and has a poor visual prognosis.[33]

Primary Prevention

Patients with known risk factors for retinal detachment should have serial dilated fundus examinations with scleral depression, often yearly. Protective eyewear is recommended for individuals with high myopia that participate in contact sports, and patients undergoing cataract surgery should be counseled about the importance of reporting symptoms of retinal tears and detachments.

Prognosis

Anatomic success exceeds 90% with modern surgical techniques.[34][35][36] Better clinical outcomes are associated with macular status (i.e. preoperative macular attachment), duration of retinal detachment prior to surgical intervention (if indicated), and absence of proliferative vitreoretinopathy.[37][38] Early detection and prompt repair remain the strongest prognostic factors.

Future Directions

Emerging innovations include:

- Ultra-high-speed wide-field OCT for real-time RD detection.[39]

- 3D surgical visualization systems enhancing precision and ergonomics.[40]

- Robotic-assisted vitreoretinal surgery.[41]

- Artificial intelligence algorithms for automated detection of retinal breaks and early detachment.[42]

- Gene therapy and molecular modulation targeting PVR prevention.[43]

Additional Resources

- Gudgel DT, Boyd K, McKinney JK. Flashes of Light. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/symptoms/flashes-of-light-list. Accessed March 13, 2019.

- Boyd K, Maturi RK. Retinal Detachment. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/retinal-detachment-list. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- The American Society of Retina Specialists. http://www.asrs.org/

References

- ↑ Haimann MH, Burton TC, Brown CK. Epidemiology of retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. Feb 1982; 100(2):289-92.

- ↑ Go SL, Hoyng CB, Klaver CC. Genetic risk of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a familial aggregation study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123: 1237-41.

- ↑ Gonin J. Treatment of detached retina by searing the retinal tears. Arch Ophthalmol 1930;4:621-625.

- ↑ https://eyerounds.org/atlas/pages/rhegmatogenous-ret-detach.htm#gsc.tab=0

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Lin JB, Narayanan R, Philippakis E, Yonekawa Y, Apte RS. Retinal detachment. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):18. Published 2024 Mar 14. doi:10.1038/s41572-024-00501-5

- ↑ https://www.aao.org/education/image/traction-rd-secondary-to-proliferative-diabetic-re

- ↑ Öhman T, Gawriyski L, Miettinen S, Varjosalo M, Loukovaara S. Molecular pathogenesis of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):966. Published 2021 Jan 13. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80005-w

- ↑ https://eyerounds.org/atlas/pages/Central-Serous-Retinopathy-CSR.html#gsc.tab=0

- ↑ Shah DN, Al-Moujahed A, Newcomb CW, et al. Exudative Retinal Detachment in Ocular Inflammatory Diseases: Risk and Predictive Factors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;218:279-287. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2020.06.019

- ↑ Hsu YJ, Hsieh YT, Yeh PT, Huang JY, Yang CM. Combined Tractional and Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy in the Anti-VEGF Era. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:917375. doi:10.1155/2014/917375

- ↑ Dai J, Zhou X, Bai H, Zeng M, Peng Q, Wu Q. Pathogenic mechanisms and treatment advances in proliferative vitreoretinopathy: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025;104(39):e44804. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000044804

- ↑ Mudhar HS. A brief review of the histopathology of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). Eye (Lond). 2020;34(2):246-250. doi:10.1038/s41433-019-0724-4

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 D'Amico DJ. Clinical practice. Primary retinal detachment. N Engl J Med. 2008 Nov 27;359(22):2346-54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804591. PMID: 19038880.

- ↑ Guber J, Bentivoglio M, Valmaggia C, Lang C, Guber I. Predictive Risk Factors for Retinal Redetachment Following Uncomplicated Pars Plana Vitrectomy for Primary Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 14;9(12):4037. doi: 10.3390/jcm9124037. PMID: 33327511; PMCID: PMC7764930.

- ↑ Wakabayashi T, Liu CK, Momenaei B, Nahar A, Yu J, Nguyen MK, Pashaee B, Vemula S, Williamson JE 3rd, Durrani A, Hsu J, Garg SJ, Kuriyan AE, Yonekawa Y; Delayed Retinal Detachment Study Group. Delayed-Onset Recurrent Retinal Detachment More Than One Year After Pneumatic Retinopexy, Scleral Buckle, or Vitrectomy for Primary Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Repair: Incidence, Characteristics, and Outcomes. Retina. 2025 May 7. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000004518. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40359469.

- ↑ Modified from Hilton GF, McLean EB, Brinton DA, eds. Retinal Detachment: Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Ophthalmology Monograph 1. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 1995.

- ↑ "This image was originally published in the Retina Image Bank® website. Author/Photographer: Manuel Ángel Alcántara Delgado, MD. Shafer's Sign. Retina Image Bank. 2020; 45624. ©the American Society of Retina Specialists".

- ↑ Lincoff H, Gieser R. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85(5):565-569.

- ↑ https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/rhegmatogenous-retinal-detachment-features-part-1

- ↑ Miao A, Xu J, Wei K, et al. Comparison of B-Scan ultrasonography, ultra-widefield fundus imaging, and indirect ophthalmoscopy in detecting retinal breaks in cataractous eyes. Eye (Lond). 2024;38(13):2619-2624. doi:10.1038/s41433-024-03093-2

- ↑ Paris JE, Macri CZ, Lee YM, Chan WO. Retinal imaging options for differentiating degenerative retinoschisis from retinal detachment: A scoping review. Surv Ophthalmol. Published online October 3, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2025.08.018

- ↑ Lee SY, Joe SG, Kim JG, Chung H, Yoon YH. Optical coherence tomography evaluation of detached macula from rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(6):1071-1076. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2008.01.031

- ↑ Kim SJ, Lim JI, Bailey ST, Kovach JL, Vemulakonda GA, Ying G, Flaxel CJ. Diabetic Retinopathy Preferred Practice Pattern 2024. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed Nov 8, 2025. https://www.aao.org/education/preferred-practice-pattern/diabetic-retinopathy-ppp.

- ↑ Lahham S, Shniter I, Thompson M, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Retinal Detachment, Vitreous Hemorrhage, and Vitreous Detachment in the Emergency Department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192162. Published 2019 Apr 5. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2162

- ↑ Tsui JC, Brucker AJ, Kolomeyer AM. Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment with Concurrent Choroidal Detachment and Macular Hole Formation After Uncomplicated Cataract Extraction and Intraocular Lens Implantation: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2024;18(2):168-172. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000001359

- ↑ Yan X, Xu M, Su F. Surgical managements for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2024;19(11):e0310859. Published 2024 Nov 14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0310859

- ↑ Kunikata H, Abe T, Nakazawa T. Historical, Current and Future Approaches to Surgery for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2019;248(3):159-168. doi:10.1620/tjem.248.159

- ↑ Schwartz SG, Flynn HW Jr, Mieler WF. Update on retinal detachment surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(3):255-261. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835f8e6b

- ↑ [Dr Amrit Sahil Panjwani]. Treatment of Retinal Detachment (Video). Available at: https://youtu.be/g4dZksCd_Ik

- ↑ Brucker AJ, Hopkins TB. Retinal Detachment Surgery: The Latest in Current Management. Retina. 2006; 26: S28-S33.

- ↑ Leaver PK. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 October; 79(10): 871–872.

- ↑ Tsui JC, Brucker AJ, Kim BJ, Kolomeyer AM. Combined Rhegmatogenous Retinal and Choroidal Detachment: A Systematic Review. Retina. 2023;43(8):1226-1239. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000003770

- ↑ Girard P, Mimoun G, Karpouzas I, et al. Clinical risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy after retinal detachment surgery. Retina.1995;14:417–424.

- ↑ Xu C, Wu J, Li Y, Zhang R, Feng C. Clinical characteristics of primary pars plana vitrectomy combined with air filling for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):7916. Published 2022 May 12. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12154-z

- ↑ Begaj T, Marmalidou A, Papakostas TD, et al. Outcomes of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair with extensive scleral-depressed vitreous removal and dynamic examination. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239138. Published 2020 Sep 24. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239138

- ↑ Haugstad M, Moosmayer S, Bragadόttir R. Primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment - surgical methods and anatomical outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(3):247-251. doi:10.1111/aos.13295

- ↑ van Bussel EM, van der Valk R, Bijlsma WR, La Heij EC. Impact of duration of macula-off retinal detachment on visual outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature. Retina. 2014;34(10):1917-1925. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000296

- ↑ Sothivannan A, Eshtiaghi A, Dhoot AS, et al. Impact of the Time to Surgery on Visual Outcomes for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Repair: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;244:19-29. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2022.07.022

- ↑ Ong J, Zarnegar A, Corradetti G, Singh SR, Chhablani J. Advances in Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging Technology and Techniques for Choroidal and Retinal Disorders. J Clin Med. 2022;11(17):5139. Published 2022 Aug 31. doi:10.3390/jcm11175139

- ↑ Razavi P, Cakir B, Baldwin G, D'Amico DJ, Miller JB. Heads-Up Three-Dimensional Viewing Systems in Vitreoretinal Surgery: An Updated Perspective. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:2539-2552. Published 2023 Aug 28. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S424229

- ↑ Iordachita II, de Smet MD, Naus G, Mitsuishi M, Riviere CN. Robotic Assistance for Intraocular Microsurgery: Challenges and Perspectives. Proc IEEE Inst Electr Electron Eng. 2022;110(7):893-908. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2022.3169466

- ↑ Chatzimichail E, Feltgen N, Motta L, et al. Transforming the future of ophthalmology: artificial intelligence and robotics' breakthrough role in surgical and medical retina advances: a mini review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1434241. Published 2024 Jul 15. doi:10.3389/fmed.2024.1434241

- ↑ Ferro Desideri L, Artemiev D, Zandi S, Zinkernagel MS, Anguita R. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: an update on the current and emerging treatment options. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2024;262(3):679-687. doi:10.1007/s00417-023-06264-1