Siderosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Ocular siderosis, also known as siderosis bulbi, is a specific form of metallosis that occurs due to a retained iron-containing intraocular foreign body (IOFB). The timing of the development of siderosis can vary significantly, occurring anywhere from days to years after the initial trauma.[2][3][4] The progression rate depends on several factors, including the iron content, size, and location of the foreign body within the eye.[2][3][4] When an IOFB is present in areas with high metabolism, such as the vitreous or aqueous, the condition progresses more rapidly compared to cases where the foreign body is encapsulated in tissues with lower metabolism, such as the lens or cornea.[1][5]

Etiology

The primary cause of ocular siderosis is the presence of an IOFB that contains significant amounts of metallic iron. Industrial accidents account for the majority of cases, with hammering being the most common cause at 41.7%, followed by chiseling and lathe turning, each accounting for 16.7% of cases.[5][6][7][8][3] Additional causes include injuries from electric welding, traffic accidents, explosions, nail gun incidents, and gunshot wounds. The condition is often exacerbated by delayed presentation to medical care or missed diagnoses following the initial trauma.[1]

Epidemiology

The demographic most commonly affected by ocular siderosis consists of males between 22 and 25 years of age.[3][7][9] Studies have shown that metallic foreign bodies comprise between 78% and 86% of all IOFBs, with iron being the predominant metal, followed by lead in frequency.[7][10][11]

Pathophysiology

The damage caused by ocular siderosis occurs through two primary mechanisms: direct cellular damage and indirect vascular damage. These processes work in distinct but complementary ways, leading to ocular tissue injury.[12][13]

Direct Siderosis

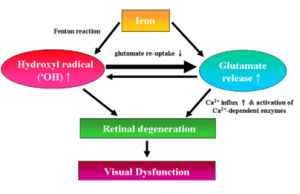

The mechanism of direct cellular damage involves elemental iron ions that generate hydroxyl radicals through complex chemical processes known as the Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions (shown below). Trivalent or ferric iron (Fe3+) and molecular oxygen radical (O2•-) produce Fe2+, which then goes on to react with hydrogen peroxide to produce the hydroxyl radical (OH•), which is a strong oxidizing agent. Because Fe3+ is regenerated by this process, and O2•- and H2O2 are naturally produced during aerobic metabolism, only a small amount of Fe3+ is required as a catalyst to continue to drive the reaction. This process is particularly efficient because it requires only a small amount of Fe3+ to act as a catalyst, continuously producing hydroxyl radicals that serve as powerful oxidizing agents.[14][15][16]

Within the retina, this process initiates a cascade of damaging events. OH• can lead to a massive release of glutamate that leads to calcium ion influx, followed by excitotoxicity and cellular apoptosis. The process also results in intracellular iron accumulation within lysosomes, leading to their dysfunction and subsequent leakage of ferritin, hemosiderin, and lysosomal contents.[17] Additionally, this process may activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, further contributing to iron-induced tissue damage.[13]

The direct effects of siderosis include pyknosis and degeneration of photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), along with inner retinal edema. Rod photoreceptors show greater susceptibility to damage compared to cones due to different protective mechanisms against oxidative damage and retinopathic factors, including light-induced degeneration and vitamin A deficiency.[18] In addition, iron can be trafficked by Müller cells cause further damage.[19] Iron ions can even diffuse posterior to anterior across the vitreous to eventually the reach the aqueous. The ions can then access the trabecular meshwork, and then reach the suprachoroidal space, diffuse to the choroid and Bruch’s membrane until finally arriving at the RPE posteriorly.[20][21] Therefore, in the early phase of siderosis, photoreceptors and RPE cells show damage histologically, while Bruch’s membrane, the choroid, and the inner retinal layers are spared.[18]

Indirect Siderosis

Indirect siderosis, also referred to as vascular siderosis, involves damage to vascular tissue that results in injury to areas distant from the foreign body's location.[24] In this process, iron forms associations with acid mucopolysaccharides in the vascular adventitia. This interaction leads to toxic microvasculopathy and uncontrolled macrophage activity, ultimately causing damage to retinal capillaries.[24][25] Of note, the retinal capillaries are the sole vascular supply to the inner retinal layers, and as such, the combination of effects from direct siderosis and indirect siderosis lead to the involvement of the inner and outer retina.[26]

Histopathology

Iron deposits accumulate in multiple ocular structures, including the corneal endothelium, Descemet's membrane, trabecular meshwork, pupillary muscles, and various epithelial layers throughout the eye.[27][1] When tissue samples are examined with Prussian blue staining, iron deposits become visible in ocular epithelial structures, in conjunction with trabecular meshwork scarring and retinal gliosis.[28] Electron microscopic examination reveals the presence of intracellular siderosomes (aggregates of hemosiderin and ferritin, possibly derived from lysosomes) within the lens epithelium and corneal keratocytes.[27]

Clinical Manifestations

The presentation of ocular siderosis includes both early and late manifestations, with specific changes occurring in various ocular tissues.

Early Signs

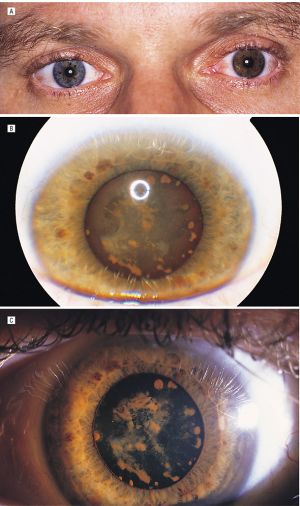

The initial manifestations of ocular siderosis typically include mydriasis and iris heterochromia.[29][30][31] These signs may be subtle but are important indicators of the condition's onset.

Late Signs

As the condition progresses, patients develop a range of vision-related symptoms and structural changes. These include progressive visual field loss and difficulty seeing at night (nyctalopia), with decreased color vision (dyschromatopsia) being less common.[4][27] Patients may also develop cataracts and/or secondary open-angle glaucoma, experience retinal arteriolar narrowing, and show signs of pigmentary retinal degeneration.[27][32] Less commonly, patients may develop intraocular inflammation, with anterior, posterior, and panuveitis all described previously.[33][34] In young patients, the condition can lead to strabismus or amblyopia due to the decreased vision in the affected eye.[35]

Specific Tissue Changes

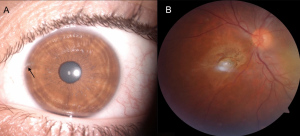

Cornea

The corneal involvement in siderosis is characterized by iron granule deposition throughout its layers, though these deposits are typically more prominent in the deeper layers. The cornea may develop a rust-colored appearance, though this usually occurs late in the disease course.[29][36]

Trabecular Meshwork

Involvement of the trabecular meshwork can result in secondary open-angle glaucoma, which occurs in approximately 5% of cases. The accumulation of iron in this structure may lead to trabecular fibrosclerosis. The resulting glaucoma is often resistant to medical management. Examination reveals irregular, scattered, black blotches in the anterior chamber angle.[4][2][36]

Iris & Pupil

Patients typically develop acquired hyperchromic heterochromia, giving the iris a brown or rusty appearance from the stromal deposition of iron. This also affects pupillary function, leading to anisocoria and abnormal pupillary reaction. Some patients develop a tonic or Adie's pupil with light-near dissociation, known as "iron mydriasis."[30][31][38][39][40][41] The affected pupil may show hypersensitivity to diluted pilocarpine as seen in Adie's pupil.[31][42]

Lens

The lens may develop a yellow-brown or rusty appearance due to the presence of minute dots of intracellular iron.[43] Focal rusty-brown nodules may form as part of a subcapsular cataract, which can potentially progress to a mature cataract.[27][37] If the iron foreign body is embedded in the lens, there may be progression to a mature cataract, with diffusion of ionizable iron throughout the lens fibers. The iron appears to bind to enzymes within these cells and becomes insoluble and incorporated in phagolysosomes with eventual cellular degeneration.[44][45]

Retina and Optic Nerve

The retinal manifestations of siderosis are extensive and include iron concentration in the RPE and inner limiting membrane.[18][27] The condition leads to photoreceptor cell necrosis and early functional damage, followed by both inner retinal and RPE degeneration. As the disease progresses, patients may develop full-thickness retinal degeneration accompanied by secondary gliosis. Functional damage to the retina occurs at a very early stage, before extensive siderosis is apparent, and before stainable iron is detected in retinal tissues.[32] [46][47] The retinal vasculature shows arteriolar narrowing and sheathing, and pigmentary changes similar to retinitis pigmentosa may occur.[48][49] Some patients develop optic atrophy, disc swelling or hyperemia, and cystoid macular edema. Optic atrophy ensues after longstanding disruption of retinal function.[14][42][50][51][52]

Diagnosis

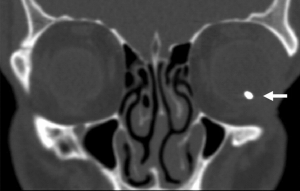

The diagnosis of ocular siderosis requires a comprehensive evaluation approach utilizing various imaging and diagnostic studies. Please see the separate page on IOFB for further information on diagnosis of IOFB.

Imaging and Additional Studies

Please see the separate page on IOFB for full details on imaging and evaluation of IOFB. In terms of diagnosis of siderosis, if there is a high clinical suspicion for siderosis and no previously known IOFB, computed tomography (CT) serves as the gold standard for detecting metallic IOFBs. Ultrasound may be useful for evaluating associated pathology, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is contraindicated when ferromagnetic material is suspected.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides valuable information about retinal involvement. OCT may demonstrate inner retinal atrophy after prolonged siderosis, as well as highlight associated pathology such as cystoid macular edema.[54][55] Fluorescein angiography may also help delineate the extent of posterior segment involvement, with reports of fluorescein angiography demonstrating hyperfluorescent window defects and ischemic maculopathy in siderosis.[26][56]

Electroretinography (ERG) plays a crucial role in monitoring disease progression. In particular, full-field ERG (ffERG) testing is used to examine the degree of ocular injury from siderosis and to monitor ocular recovery after metallic foreign body removal, and can be used as an efficient diagnostic and prognosticating tool in both clinical and subclinical ocular siderosis.[57] The progression of siderosis can be tracked through characteristic ERG changes. Initially, patients show hypernormal a- and b-waves, followed by a progressive decrease in wave amplitudes over the initial 1-2 years. The reduction in b-wave amplitude occurs earlier than other clinical signs.[58] Other early predictors of siderosis on ERG include reduction of oscillatory potential amplitude reduction and P1 and N1 wave decreased amplitude with delay in P1-inplict time on multifocal ERG (even in presence of normal ffERG).[59][60][61] Importantly, up to 40% of amplitude loss may be reversible with appropriate treatment.[38]

EOG changes may not occur in eyes with metallic intraocular foreign bodies presumably because of sparing of the outer segments of the rod and the retinal pigment epithelium. EOG abnormalities indicate severe metallosis and poor visual prognosis.[1]

Management

The management strategy varies depending on whether the case is acute or chronic, with specific considerations for each scenario. For acute IOFB management, see separate page on Intraocular Foreign Bodies.

Chronic Cases

In chronic cases, the decision to remove the foreign body depends on several factors. Removal is indicated when there is recurrent intraocular inflammation or progressive retinal damage documented by serial ERG.[62][47] In cases where the IOFB is located in the subretinal space or within a clear lens, observation may be considered as an alternative to immediate removal. Regular monitoring of visual acuity, clinical signs, and ERG is essential for all patients.

Deferoxamine, an iron chelating agent, has a limited role in the management of ocular siderosis. While subconjunctival administration of 10-100 mg may help prevent damage in early cases, it has not shown effectiveness in advanced cases.[63][64][65][66] The significant side effects associated with deferoxamine limit its clinical utility, and it is not recommended for routine management of the condition.

Conclusions

Ocular siderosis is a serious condition that results from retained iron-containing IOFBs. Early detection and appropriate management are crucial for preventing permanent vision loss. The diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical findings, imaging studies, and electroretinography, with ERG serving as a particularly valuable tool for monitoring disease progression and guiding treatment decisions. While removal of the foreign body is generally indicated in acute cases, management of chronic cases requires careful consideration of various factors, including the location of the IOFB and evidence of progressive damage. Regular monitoring is essential for all patients, as the condition can progress over time even in seemingly stable cases. With proper diagnosis and timely intervention, the sight-threatening effects of siderosis can often be mitigated, though prevention through appropriate eye protection during high-risk activities remains the best approach to avoiding this condition.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Casini G, Sartini F, Loiudice P, Benini G, Menchini M. Ocular siderosis: a misdiagnosed cause of visual loss due to ferrous intraocular foreign bodies—epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical signs, imaging and available treatment options. Documenta Ophthalmologica. 2021;142(2):133-152. doi:10.1007/s10633-020-09792-x

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kannan NB, Adenuga OO, Rajan RP, Ramasamy K. Management of Ocular Siderosis: Visual Outcome and Electroretinographic Changes. Teoh SCB, ed. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016;2016:7272465.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Zhu L, Shen P, Lu H, Du C, Shen J, Gu Y. Ocular Trauma Score in Siderosis Bulbi With Retained Intraocular Foreign Body. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Sep;94(39):e1533.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Ballantyne JF. Siderosis bulbi. Br J Ophthalmol. 1954 Dec;38(12):727-733.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Acharya I, Raut AA. Siderosis Bulbi. [Updated 2022 Feb 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567781/

- ↑ Jonas JB, Knorr HL, Budde WM. Prognostic factors in ocular injuries caused by intraocular or retrobulbar foreign bodies. Ophthalmology. 2000 May;107(5):823-8.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Greven CM, Engelbrecht NE, Slusher MM, Nagy SS. Intraocular foreign bodies: management, prognostic factors, and visual outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2000 Mar;107(3):608-12.

- ↑ Kong Y, Tang X, Kong B, Jiang H, Chen Y. Six-year clinical study of firework-related eye injuries in North China. Postgrad Med J. 2015 Jan;91(1071):26-9.

- ↑ Khani SC, Mukai S. Posterior segment intraocular foreign bodies. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1995 Winter;35(1):151-61.

- ↑ Wu TT, Kung YH, Sheu SJ, Yang CA. Lens siderosis resulting from a tiny missed intralenticular foreign body. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009 Jan;72(1):42-4.

- ↑ Demircan N, Soylu M, Yagmur M, Akkaya H, Ozcan AA, Varinli I. Pars plana vitrectomy in ocular injury with intraocular foreign body. J Trauma. 2005 Nov;59(5):1216-8.

- ↑ Richter GW. The iron-loaded cell--the cytopathology of iron storage. A review. Am J Pathol. 1978;91(2):362-404.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Gelfand BD, Wright CB, Kim Y, et al. Iron Toxicity in the Retina Requires Alu RNA and the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cell Reports. 2015;11(11):1686-1693. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.05.023

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sandhu HS, Young LH. Ocular Siderosis. International Ophthalmology Clinics. 2013;53(4):177-184.

- ↑ Dziubla T, Butterfield DA. 1.2.4 Fenton/Haber-Weiss Chemistry. In: Oxidative Stress and Biomaterials. Elsevier/Academic Press; 2016:12-14.

- ↑ Casini G, Sartini F, Loiudice P, Benini G, Menchini M. Ocular siderosis: a misdiagnosed cause of visual loss due to ferrous intraocular foreign bodies—epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical signs, imaging and available treatment options. Documenta Ophthalmologica. 2021;142(2):133-152. doi:10.1007/s10633-020-09792-x

- ↑ Chao HM, Chen YH, Liu JH, et al. Iron-generated hydroxyl radicals kill retinal cells in vivo: effect of ferulic acid. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27(4):327-339. doi:10.1177/0960327108092294

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Masciulli L, Anderson DR, Charles S. Experimental Ocular Siderosis in the Squirrel Monkey. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1972;74(4):638-661. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(72)90826-4

- ↑ Tawara A. Transformation and cytotoxicity of iron in siderosis bulbi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27(2):226-236.

- ↑ Appel I, Barishak YR. Histopathological Changes in Siderosis Bulbi. Ophthalmologica. 1978;176(4):205-210.

- ↑ Gerkowicz K, Prost M. Experimental Investigations on the Penetration into the Eyeball of Iron Administered Intraorbitally. Ophthalmologica. 1984;188(4):239-242.

- ↑ Casini G, Sartini F, Loiudice P, Benini G, Menchini M. Ocular siderosis: a misdiagnosed cause of visual loss due to ferrous intraocular foreign bodies—epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical signs, imaging and available treatment options. Documenta Ophthalmologica. 2021;142(2):133-152. doi:10.1007/s10633-020-09792-x

- ↑ Chao HM, Chen YH, Liu JH, et al. Iron-generated hydroxyl radicals kill retinal cells in vivo: effect of ferulic acid. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27(4):327-339. doi:10.1177/0960327108092294

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Cibis PA, Yamashita T. Experimental Aspects of Ocular Siderosis and Hemosiderosis*. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1959;48(5):465-480.

- ↑ Dhoble P, Velis G, Sivakaumar P. Encapsulated metallic intraocular foreign body of long duration presenting with cystoid macular edema and normal full-field electroretinogram. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2019;12(1):50-52.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Shaikh S, Blumenkranz MS. Fluorescein angiographic findings in ocular siderosis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;131(1):136-138.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 Hope-Ross M, Mahon GJ, Johnston PB. Ocular siderosis. Eye (Lond). 1993;7 (Pt 3):419-425.

- ↑ Yang Z,Yang XL,Xu LS,Dai L,Yi MC. Application of Prussian blue staining in the diagnosis of ocular siderosis. Int J Ophthalmol 2014;7(5):790-794.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Barr CC, Vine AK, Martonyi CL. Unexplained heterochromia. Intraocular foreign body demonstrated by computed tomography. Survey of Ophthalmology. 1984;28(5):409-411.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Welch RB. Two remarkable events in the field of intraocular foreign body: (1) The reversal of siderosis bulbi. (2) The spontaneous extrusion of an intraocular copper foreign body. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1975;73:187-203.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Monteiro ML, Ulrich RF, Imes RK, Fung WE, Hoyt WF. Iron mydriasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984 Jun;97(6):794-796

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Kuhn F, Kovacs B. Management of postequatorial magnetic intraretinal foreign bodies. Int Ophthalmol. 1989 Sep;13(5):321-325.

- ↑ Politis M, Rosin B, Amer R. Ocular Siderosis Subsequent to a Missed Pars Plana Metallic Foreign Body that Masqueraded as Refractory Intermediate Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26(4):598-600.

- ↑ Yeh S, Ralle M, Phan IT, Francis PJ, Rosenbaum JT, Flaxel CJ. Occult intraocular foreign body masquerading as panuveitis: inductively coupled mass spectrometry and electrophysiologic analysis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2012 Jun;2(2):99-103

- ↑ Meier P. Combined anterior and posterior segment injuries in children: a review. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2010;248(9):1207-1219.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Kearns M, McDonald R. Generalised siderosis from an iris foreign body. Aust J Ophthalmol. 1980 Nov;8(4):311-313.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Pollack A, Oliver M. Reversal of Siderosis. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1998;116(5):678-679.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Weiss MJ, Hofeldt AJ, Behrens M, Fisher K. Ocular siderosis. Diagnosis and management. Retina. 1997;17(2):105-108.

- ↑ Verhoeff FH. SIDEROSIS BULBI. Br J Ophthalmol. 1918 Nov;2(11):571-573.

- ↑ Black NM. Siderosis Bulbi with Dilated Inactive Pupil. Recovery of Pupillary Activity After Removal of Foreign Body. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1923;21:171-182.

- ↑ Wilhelm H. Neuro-ophthalmology of pupillary function--practical guidelines. J Neurol. 1998 Sep;245(9):573-83.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Dowlut MS, Curragh DS, Napier M, et al. The varied presentations of siderosis from retained intraocular foreign body. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2019;102(1):86-88.

- ↑ Wolkow N, Song Y, Wu TD, Qian J, Guerquin-Kern JL, Dunaief JL. Aceruloplasminemia: retinal histopathologic manifestations and iron-mediated melanosome degradation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(11):1466-1474.

- ↑ Siantar RG, Agrawal R, Heng LW, Ho BC. Histopathologically proven siderotic cataract with disintegrated intralenticular foreign body. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013 Jan-Feb;61(1):30-32

- ↑ Rychener RO. Siderosis following intralenticular foreign body. Am J Ophthalmol. 1946 Mar;29:346

- ↑ Knave B. Long-term changes in retinal function induced by short, high intensity flashes. Experientia. 1969;25(4):379-380.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Sneed SR, Weingeist TA. Management of Siderosis Bulbi due to a Retained Ironcontaining Intraocular Foreign Body. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(3):375-379.

- ↑ Pastor JC, Rojas J, Pastor-Idoate S, Di Lauro S, Gonzalez-Buendia L, Delgado-Tirado S. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: A new concept of disease pathogenesis and practical consequences. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2016;51:125-155.

- ↑ Yamaguchi K, Tamai M. Siderosis bulbi Induced by Intraocular Lens Implantation (With 1 color plate). Ophthalmologica. 1989;198(3):113-115.

- ↑ Slusher MM, Sarin LK, Federman JL. Management of intraretinal foreign bodies. Ophthalmology. 1982 Apr;89(4):369-373.

- ↑ Elgin U, Eranil S, Simsek T, Batman A, Ozdamar Y, Ozkan SS. Siderosis Bulbi Resulting From an Unknown Intraocular Foreign Body. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2008;65(4).

- ↑ Xie H, Chen S. Ocular siderosis. Eye Sci. 2013;28(2):108-112.

- ↑ Pinto A, Brunese L, Daniele S, et al. Role of Computed Tomography in the Assessment of Intraorbital Foreign Bodies. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 2012;33(5):392-395. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2012.06.004

- ↑ Lee YH, Kim YC. Optical coherence tomographic findings of ocular siderosis following intraocular foreign body removal: a case report. Medicine. 2020 Jul 24;99(30):e21476.

- ↑ Dhoble PY, Velis GB, Sivakaumar P. Encapsulated metallic intraocular foreign body of long duration presenting with cystoid macular edema and normal full-field electroretinogram. Oman Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019 Jan 1;12(1):50-2.

- ↑ Schocket SS, Lakhanpal V, Varma SD. Siderosis from a retained intraocular stone. Retina. 1981;1(3):201-207.

- ↑ Karpe G. Early diagnosis of siderosis retina by the use of electroretinography. Doc Ophthalmol. 1948;2(1 vol.):277-96.

- ↑ Katz SE. Ocular trauma: principles and practice. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80(3):196.

- ↑ Tanabe J, Shirao Y, Oda N, Kawasaki K. Evaluation of retinal integrity in eyes with retained intraocular metallic foreign body by ERG and EOG. Doc Ophthalmol. 1992;79(1):71-78.

- ↑ Gupta S, Midha N, Gogia V, Sahay P, Pandey V, Venkatesh P. Sensitivity of multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) in detecting siderosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2015 Dec;50(6):485-490.

- ↑ Sahay P, Kumawat D, Gupta S, Tripathy K, Vohra R, Chandra M, Venkatesh P. Detection and monitoring of subclinical ocular siderosis using multifocal electroretinogram. Eye (Lond). 2019 Oct;33(10):1547-1555.

- ↑ Kuhn F, Witherspoon CD, Skalka H, Morris R. Improvement of siderotic ERG. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1992 Jan-Mar;2(1):44-45.

- ↑ Tandias R, Rossin E, Davies E. Subconjunctival deferoxamine for corneal rust deposits associated with ocular siderosis: A case report.

- ↑ Gerkowicz K, Prost M. Experimental investigations on the effect of desferrioxamine on the aqueous level of iron administered intraorbitally. Ophthalmologica. 1984 Mar 31;189(3):139-42.

- ↑ Declercq SS. Desferrioxamine in ocular siderosis: a long-term electrophysiological evaluation. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1980 Aug 1;64(8):626-9.

- ↑ Wise JB. Treatment of experimental siderosis bulbi, vitreous hemorrhage, and corneal bloodstaining with deferoxamine. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1966 May 1;75(5):698-707.