Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Overview

Tolosa–Hunt Syndrome (THS) is a rare, idiopathic granulomatous inflammatory disorder involving the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure, or orbital apex, characterized clinically by painful ophthalmoplegia. It describes episodic orbital pain associated with paralysis of one or more of the third, fourth and/or sixth cranial nerves, which usually resolves spontaneously but can relapse and remit. The condition typically responds rapidly to corticosteroid therapy. Accurate diagnosis requires exclusion of other causes of painful ophthalmoplegia, such as neoplasm, infection, or systemic inflammatory disease.

History

It was first described in 1954 by Tolosa, who found granulomatous inflammation in the cavernous sinus during autopsy of a patient with severe left-sided trigeminal pain and total ophthalmoplegia[1]. In 1961, Hunt reported 6 cases of unilateral painful ophthalmoplegia that tested negative with angiography and lumbar puncture and characterized the steroid responsiveness of this disorder.[1]

Epidemiology

- Incidence: Estimated <1 case per million per year.[2]

Disease Entity

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome was first classified by the International Headache Society in 2004 and now is a part of Classification ICHD-3. ICD-10 for Tolosa Hunt Syndrome is H49.40.

Disease

Unilateral orbital or periorbital pain with paresis of third, fourth and/or sixth cranial nerves secondary to idiopathic inflammation of the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure or orbit.

The ICHD-3 Diagnostic criteria for Tolosa-Hunt syndrome are as follows[5]:

A. Unilateral orbital or periorbital headache fulfilling criterion C

B. Both of the following:

a. Granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure or orbit, demonstrated by MRI or biopsy

b. Paresis of one or more of the ipsilateral third, fourth, and/or sixth cranial nerves.

C. Evidence of causation demonstrated by both of the following:

a. Headache is ipsilateral to the granulomatous inflammation

b. Headache has preceded paresis of the third, fourth, and/or sixth nerves by ≤2 weeks, or developed with it.

D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis (see differential diagnosis section for more detail)

Of note:

Some reported cases of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome had additional involvement of the trigeminal nerve (commonly the first division) or optic, facial or acoustic nerves. Sympathetic innervation of the pupil is occasionally affected.

The syndrome has been caused by granulomatous material in the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure or orbit in some biopsied cases.

Careful follow-up is required to exclude other possible causes of painful ophthalmoplegia, such as orbital apex syndrome, superior orbital fissure syndrome, cavernous sinus syndrome, or herpes zoster ophthalmicus, as more hazardous conditions may lead to frozen globe (total ophthalmoplegia).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The underlying cause is idiopathic, sterile granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus or adjacent structures.[2][4][6]

- Histopathology demonstrates fibroblastic, lymphocytic, and plasmocytic infiltration – noncaseating granulomas with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and occasional giant cells.

- Pathology may extend to involve the superior orbital fissure (sphenocavernous or parasellar syndrome) or orbital apex and affect the optic nerve.

- The inflammatory process involves cranial nerves III, IV, V1, and VI, producing the hallmark ophthalmoplegia and pain. Involvement of the sympathetic fibers in the cavernous ICA or parasympathetic fibers that surround the oculomotor nerve (CN III) can also occur secondary to granulomatous inflammation.

- Possible overlap exists with IgG4-related disease, sarcoidosis, or autoimmune vasculitides.

- No infectious or neoplastic etiology is identified in classic THS, though a possible risk factor is a recent viral infection.

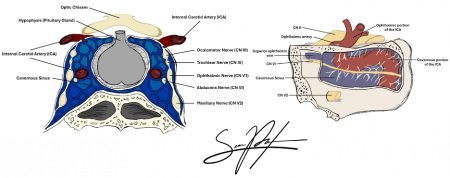

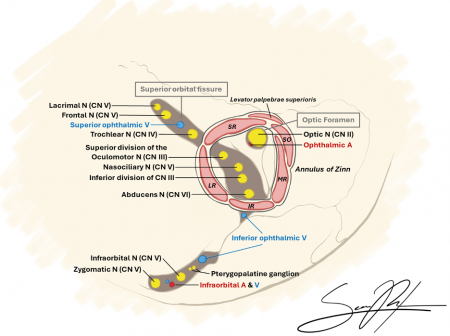

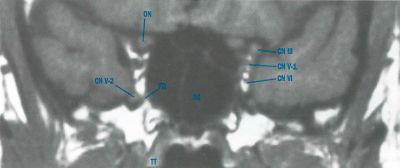

Anatomy

Key structures affected:

- Cavernous sinus

- Superior orbital fissure

- Orbital apex

Cranial nerves III, IV, VI, and the ophthalmic branch of V (V1), as well as other neurovasculature structures, traverse these regions, explaining the characteristic clinical features.

Clinical Presentation

The hallmark is unilateral orbital pain followed within days by ophthalmoplegia. Pain is typically sharp, retro-orbital, and constant. Ocular motor deficits depend on the nerves involved.

| Cranial Nerve | Function Affected | Common Clinical Findings |

|---|---|---|

| III (Oculomotor) | Eye adduction, elevation, ptosis | Diplopia, ptosis, “down and out” eye |

| IV (Trochlear) | Eye depression in adduction | Vertical diplopia |

| VI (Abducens) | Eye abduction | Horizontal diplopia |

| V1 (Ophthalmic) | Forehead sensation | Sensory loss or hypoesthesia in V1 distribution |

Other findings:

- Orbital or temporal pain preceding ophthalmoplegia[2][7]

- Possible proptosis or chemosis (from inflammation)[2][4]

- Rare visual loss (if optic nerve or orbital apex involvement)[8]

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Painful ophthalmoparesis or ophthalmoplegia is the hallmark of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome[9]. The patient may complain of double vision worse at distance, headaches, dizziness, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, blurred vision, and a “boring” pain may be associated with the headache. Rare and extensive cases may result in a “frozen globe,” or complete unilateral ophthalmoplegia.[10]

Physical Exam

In addition to the standard ophthalmic examination of the patient including vision, IOP, pupil check for APD and nystagmus, slit-lamp and dilated fundus exam, a complete sensorimotor exam should be done. This includes oculomotor exam (to check for esotropia, exotropia, hypertropia or hypotropia), ductions, vergence, saccades, pursuit, and head tilt/turn. A common finding is abduction deficit associated with esodeviation that increases with gaze to the affected side. Lids should be checked for ptosis or lid retraction or any change in lid aperture during eye movements (to check for aberrant regeneration). Lid strength, fatigue or variability should be noted. Facial sensation should be checked. Stereopsis and color plates should also be evaluated.

Clinical diagnosis

Involvement of multiple contiguous cranial nerves strongly suggest a lesion in the cavernous sinus or subarachnoid space. Only one nerve may be involved, most likely the sixth cranial nerve, which is the only one not protected within the dural wall of the cavernous sinus. The presence of optic nerve involvement and consequential vision loss may also lead diagnosis based off of the lesion’s anatomical location (see “Differential diagnosis” in Orbital Apex Syndrome.

In addition to the complete ophthalmic exam as described, the physician must closely look for Horner syndrome, facial hypoesthesia or engorgement of ocular surface vessels, orbital venous congestion, increased IOP or pulse pressure.

All positive findings should be noted and the differential diagnoses listed below should be considered.

Diagnostic Procedures

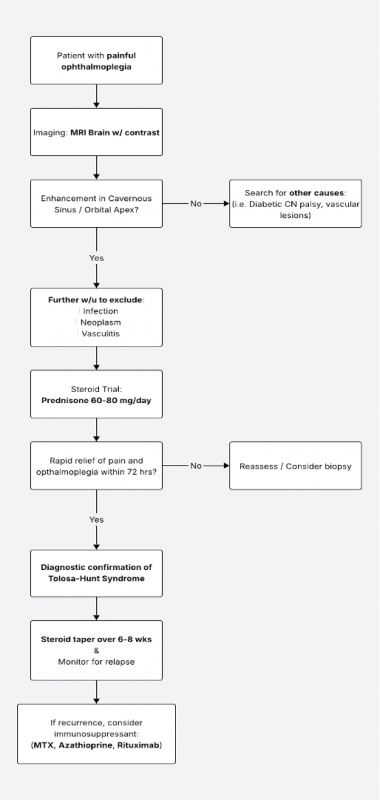

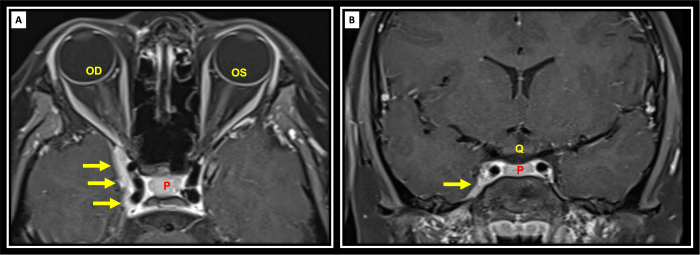

Diagnosis is clinical and radiologic, based on characteristic findings and exclusion of other causes of painful ophthalmoplegia. The most appropriate imaging includes MRI /MRA (DWI series) which provides information about the cavernous sinus and orbital apex in greater detail than a CT. MRI may be able to provide detail of granulomatous inflammation, aiding in formal diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. However, these results may be unreliable. Biopsy can also be used to demonstrate granulomatous inflammation and may be more reliable, but the procedure may be more difficult[9]

A CTA w/ and w/o contrast can also be obtained if an MRI/MRA is not available. A lumbar puncture may be done to check for opening pressure and CSF should be evaluated for infection/oligoclonal bands.

Recent evidence supports the use of High resolution 3D skull base MRI with isotropic constructive interference in steady state (CISS) and 0.6-mm cut images with and without contrast as effective way to visualize cranial nerves and cavernous sinus lesions that were not previously visualized.[11]

A. Imaging

- MRI with contrast is the gold standard.

- Typical findings:

- Enlargement and contrast enhancement of the cavernous sinus or superior orbital fissure.

- Possible extension into the orbital apex.

- Iso- or hypointense T1 signal; variable T2 signal.

CT may show nonspecific soft tissue density.

B. Laboratory Tests[12]

- Work up should include tests that can rule out the various diseases listed above given the history and context of the patient.

- ESR/CRP: may be elevated but nonspecific.

- ANA, ANCA, ACE level, IgG4, syphilis serology: to exclude systemic inflammatory, infectious, or autoimmune causes.

- In few recent reports, associations with Pathogenic Nucleotide-Binding Oligomerization Domain 2 Polymorphism[13] and COVID-19 vaccination [14] have been reported.

Lab Workup to Consider:

| Serum | Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) |

|---|---|

| CBC w/ diff | Glucose |

| ESR | Protein |

| CRP | Cell count & differential |

| RPR and FTA-ABS | Cytology |

| ACE | Gram Stain |

| ANA | Oligoclonal bands |

| p-ANCA, c-ANCA | |

| Anti dsDNA, Anti sm-antibody | |

| RF | |

| TFTs | |

| HBa1C and Fasting Glucose | |

| Lyme Panel | |

| Serum Protein Electrophoresis |

C. Biopsy

- Reserved for atypical or steroid-nonresponsive cases to exclude neoplasm or infection.

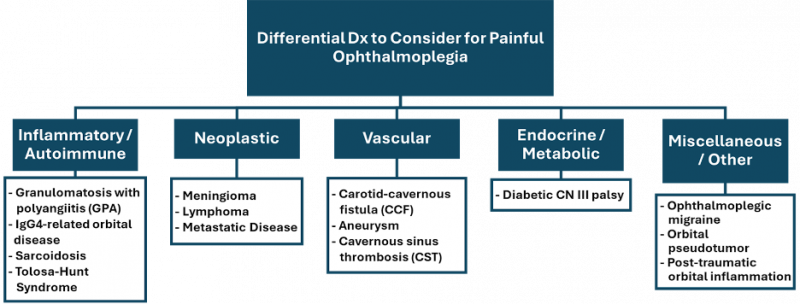

Differential Diagnosis

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. Thus, the following entities must be considered and ruled out before a diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is made:

| Category | Conditions | Distinguishing Clinical/Imaging Features | Key Diagnostic Tests | Steroid Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory/Autoimmune | Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome

Sarcoidosis GPA IgG4-related Orbital Disease |

THS: Localized to cavernous sinus/orbital apex

Sarcoid: Systemic signs (e.g. erythema nodosum) GPA: Sinus/Nasal disease IgG4: Lacrimal gland enlargement |

MRI brain/orbit w/ contrast

ACE, ANCA, IgG4 panel Chest imaging |

Rapid in Tolosa-Hunt; variable in others |

| Neoplastic | Meningioma

Lymphoma Metastatic carcinoma |

Progressive, non-steroid responsive

Often associated with mass effect on imaging |

MRI w/ contrast

Biopsy |

None or minimal |

| Infectious | Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis

Bacterial or Fungal Orbital Apex Infection Tuberculosis |

Febrile, toxic appearance

Orbital congestion, proptosis Elevated WBC, positive cultures |

Blood cultures

MRI/CT venography Fungal stains/biopsy |

None or worsens with steroids |

| Vascular | Carotid–cavernous fistula (CCF)

Cavernous sinus thrombosis (noninfectious) |

Pulsatile proptosis, bruit (CCF)

|

CTA/MRA

|

None |

| Endocrine / Metabolic | Diabetic CN III palsy | Pupil-sparing 3rd nerve palsy | HbA1c, glucose | None |

| Miscellaneous/Other | Ophthalmoplegic migraine (recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy)

Post-traumatic orbital inflammation |

Migraine history, transient palsy

Pseudotumor: diffuse orbital inflammation |

MRI

LP |

Variable; good in orbital pseudotumor |

Management

Oral steroids are the mainstay of treatment. Both symptoms and physical exam findings (headache, ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, etc) can be expected to resolve rapidly with an oral steroid taper regimen over 3-4 months. The patient can be co-managed with the Neurology service to rule out other entities listed in the differential diagnosis of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome.

Before starting steroid, fungal infection of the orbit with fungal sinusitis (mucormycosis in diabetic/immunocompromised) is a differential diagnosis that must be considered, because in that case starting steroid will worsen the disease.

Several therapies have been investigated for instances of steroid-resistant Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. A case report by Lee, et al. has been published in which gamma-knife radiation therapy is used to provide marked short-term relief without relapse of symptoms[15]. Antimetabolic agents such as methotrexate, infliximab, and mycophenolate mofetil have also been shown to cause dramatic improvement in patients whom are deemed to be steroid-resistant[16][17][18]

1. Corticosteroids

- First-line therapy.

- Rapid improvement in pain within 24–72 hours is characteristic.

- Example regimen: Prednisone 60–80 mg/day for 1–2 weeks, then gradual taper over 6–8 weeks.

2. Refractory or Relapsing Disease

- Consider steroid-sparing immunosuppressants:

- Methotrexate

- Azathioprine

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Rituximab (for suspected IgG4-related cases)

3. Follow-up

- MRI after treatment to confirm resolution.

- Monitor for recurrence (occurs in up to 30–40% of patients).

- Long-term immunology workup if recurrent or bilateral.

Prognosis

- Pain relief: Usually within days of steroid initiation.

- Ocular motility recovery: Weeks to months; may be incomplete.

- Recurrence: 30–40%, often ipsilateral.

- Long-term outcome: Excellent if promptly treated and mimics excluded.[10]

Complications

- Relapsing inflammation with cranial neuropathies.

- Persistent diplopia or ptosis if fibrosis develops.

- Steroid-related adverse effects (iatrogenic Cushing’s, osteoporosis, hyperglycemia).

Recent Advances

- High-resolution MRI (3T): Improved sensitivity for detecting subtle cavernous sinus inflammation.[6][7]

- IgG4-related overlap: Some cases of THS may represent localized IgG4-related orbital disease.[19]

- Biologic therapy: Rituximab used successfully in steroid-refractory cases.[4][19]

- Molecular imaging: PET-CT occasionally helpful to exclude systemic inflammatory disease.[19]

Key Points / Pearls

- Always exclude secondary causes before labeling as idiopathic THS.

- Steroid responsiveness supports but does not confirm diagnosis.

- Reimage if symptoms recur or fail to improve.

- Consider IgG4 testing in recurrent or atypical cases.

- Early recognition prevents unnecessary biopsy and morbidity.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tolosa E. Periarteritic lesions of the carotid siphon with the clinical features of a carotid infraclinoidal aneurysm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1954;17:300-2.doi:10.1136/jnnp.17.4.300

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Ahmed HS, Shivananda DB, Pulkurthi SR, Dias AF, Sahoo PP. Clinical profile and outcomes in Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome; a systematic review. J Clin Neurosci. 2024;129:110858. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2024.110858

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Gama BP, Silva-Néto RP. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome in Childhood and Adolescence: A Literature Review in the Last 10 Years. Neuropediatrics. 2021;52(1):1-5. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1715632

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Ahmed HS, Jayaram PR, Khar S. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Headache. 2025;65(6):1027-1040. doi:10.1111/head.14890

- ↑ Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kmeid M, Medrea I. Review of Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome, Recent Updates. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2023;27(12):843-849. doi:10.1007/s11916-023-01193-4

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hao R, He Y, Zhang H, Zhang W, Li X, Ke Y. The evaluation of ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria for Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: a study of 22 cases of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(6):899-905. doi:10.1007/s10072-015-2124-2

- ↑ Hung CH, Chang KH, Wu YM, et al. A comparison of benign and inflammatory manifestations of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(10):842-852. doi:10.1177/0333102412475238

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mullen E, Green M, Hersh E, Iloreta AM, Bederson J, Shrivastava R. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome: Appraising the ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(10):1696-1700.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bowman S, Helming A. Complete ophthalmoplegia diagnosed as Tolosa-Hunt syndrome on interval MRI. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(11):e252727. Published 2022 Nov 3. doi:10.1136/bcr-2022-252727

- ↑ Kontzialis M, Choudhri AF, Patel VR, Subramanian PS, Ishii M, Gallia GL, Aygun N, Blitz AM. High-Resolution 3D Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Sixth Cranial Nerve, J of Neuro-Ophthalmol.Dec 2015; 35(4): 412-25 doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000313

- ↑ Amrutkar C, Burton EV. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459225/

- ↑ Vegunta, Sravanthi MD; Bohnsack, John MD; Crum, Alison MD; Digre, Kathleen MD; Katz, Bradley MD, PhD; Seay, Meagan DO; Quigley, Edward MD, PhD; Kennedy, Sean MD; Mamalis, Nick MD; Warner, Judith MD. Multiple Cranial Neuropathies and Pachymeningitis in a Patient With a Pathogenic Nucleotide-Binding Oligomerization Domain 2 Polymorphism. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 41(4):p 547-552, December 2021. | DOI: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001342

- ↑ Chuang TY, Burda K, Teklemariam E, Athar K. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome Presenting After COVID-19 Vaccination. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16791. Published 2021 Jul 31. doi:10.7759/cureus.16791

- ↑ Lee JM, Park JS, Koh EJ. Gamma Knife radiosurgery in steroid-intolerant Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2016;158(1):143-5

- ↑ Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. A role for methotrexate in the management of non-infectious orbital inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(10):1220-4

- ↑ Halabi T, Sawaya R. Successful Treatment of Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome after a Single Infusion of Infliximab. J Clin Neurol. 2018;14(1):126-127

- ↑ Hatton MP, Rubin PA, Foster CS. Successful treatment of idiopathic orbital inflammation with mycophenolate mofetil. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(5):916-8

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Terrim S, Mahler JV, Filho FVM, et al. Clinical Presentation, Investigation Findings, and Outcomes of IgG4-Related Pachymeningitis: A Systematic Review. JAMA Neurol. 2025;82(2):193–199. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.3947