Central Serous Chorioretinopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC or CSCR) is the fourth most common retinopathy after age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and branch retinal vein occlusion.[1] CSC typically occurs in men in their 20s to 50s who exhibit acute or subacute central vision loss or distortion. Other common complaints include micropsia, metamorphopsia, hyperopic (most common) or myopic shift, central scotoma, and reduced contrast sensitivity and color saturation.[2] Though the exact mechanisms of CSC remain poorly understood, CSC is thought to result from hyperpermeability in choroidal capillaries and retinal pigment dysfunction, leading to a serous detachment of the neurosensory retina.[3] While subretinal fluid (SRF) in CSC may resolve spontaneously, complications such as atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), photoreceptors, and secondary macular neovascularization (MNV) can occur if the disease progresses. Recurrence occurs in about 31% of patients with CSC,[4] although the recurrence rate has been cited as 50% in some texts.

The disease was first described by Albrecht von Graefe in 1866 as relapsing central luetic retinitis.[5] Since then it has been reported under a variety of names, including idiopathic flat detachment of the macula, central angiospastic retinopathy, and central serous retinopathy.[6][7][8] However, the term idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy was coined by Gass and colleagues in 1967 after proposing that increased choroidal capillary hyperpermeability may elevate hydrostatic pressure, resulting in retinal pigment epithelial detachment (PED) and fluid leakage into the subretinal space.[3] This was confirmed later with optical coherence tomography (OCT) and indocyanine green angiography (ICGA).[9][10]

Differential Diagnosis

CSC causes unilateral vision loss, usually in males, due to development of subretinal fluid, typically between the ages of 20 and 50 years. In females, CSC usually develops at an older age. The differential diagnosis for subretinal fluid is broad and encompasses all disease entities that can cause macular neurosensory detachment. Van Dijk and Boon (2021) have described as many as 13 distinct disease categories associated with or mimicking serous maculopathy.[11] These include: ocular neovascular diseases, vitelliform lesions, inflammatory conditions like posterior scleritis or Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, ocular tumors, hematological malignancies, paraneoplastic syndromes, ocular developmental anomalies, medication- and toxicity-related conditions, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, tractional retinal detachment, retinal vascular disease, and miscellaneous conditions. Cases of bullous CSC (which is usually seen in patients on systemic steroids), where a significant amount of sub-retinal fluid is found, can be mistaken for rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Several associations for bullous CSC include a history of kidney dysfunction or autoimmune disease.[12][13]

In both acute and chronic cases that have resolved, the only clue that may be present on examination is macular RPE mottling. By definition, the patient’s retinal detachment cannot be due to another primary process. If suspected, those diagnoses should be ruled out. Multimodal imaging is essential for distinguishing between these conditions, including OCT, ICGA, fluorescein angiography (FA), fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and OCT-angiography (OCT-A). A thorough history, comprehensive eye exam, and laboratory tests can additionally help delineate between diagnoses.

Etiology

Although exact mechanisms behind CSC have not been elucidated, many associations have been found. Increased choroidal vascular permeability is postulated to occur as a response to epinephrine-mediated vasospasm that is potentiated by steroids, leading to choroidal ischemia and vascular hyperpermeability.[14] [15] Oncotic pressure in the choroidal space, combined with RPE dysfunction, leads to the accumulation of fluid in the subretinal space.[16] [17] [18][19] The currently theorized role of the RPE involves the increased hydrostatic pressure in the choroid, causing “micro-rips or blowouts” in the RPE and jeopardizing its barrier function.[20]

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Most patients who present with CSC are between the ages of 28 and 68 years, with an average age of 43 years.[21] Those who are over 50 years of age are more likely to have bilateral disease (50%) with RPE loss and choroidal neovascularization compared to those less than 50 years of age (28.4%).[22] CSC tends to affect males (9.9/100,000) about 6 times more than females (1.7/100,000).[4] Similar prevalence of CSC was noted in White, Black, and Asian populations.[23][24]

Steroids, both endogenous and exogenous, have the strongest known association with CSC. Garg and colleagues found that patients with acute CSC have higher levels of endogenous cortisol compared to age-matched controls.[25] Other studies have shown that even minimal exposure to exogenous corticosteroids (for example, intravenous, cutaneous, or nasal spray) has been associated with CSC, suggesting that the increased risk is not strictly dependent on the dose or mode of corticosteroid administration.[26] [27] [28][29] In patients with CSC, the odds ratio of systemic steroid use was found to be 37.1 (95% confidence interval (CI), 6.2–221.8), although lower odds ratios have also been described.[26][28][30][31]

Stressful life events, shift work, poor sleep quality, circadian rhythm disturbances have been associated with a higher risk of CSC.[28][32][33] Yavas and colleagues showed in a prospective study that 61% of patients with CSC had underlying obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed with overnight polysomnography.[34] Fok found that patients with psychiatric disorders such as depression are more likely to have a recurrence.[35] Several studies have found associations between CSC and certain personality traits. Individuals exhibiting Type A behavioral characteristics (e.g., intense drive, eagerness to compete, and desire for recognition and advancement) may have increased levels of catecholamines and corticosteroids, which might explain their higher risk for CSC.[36] Support for an association with Cushing syndrome comes from a prospective cohort study by Brinks and colleagues, who identified CSC-like retinal abnormalities in 3 of 11 patients with active endogenous hypercortisolism, as well as earlier cohort data showing that approximately 5% of patients with Cushing syndrome developed CSC exclusively during periods of active cortisol excess.[37][38] However, a study by van Haalen and colleagues found no significant prevalence of maladaptive personality traits (e.g., Type A) or (subclinical) Cushing's syndrome in chronic cCSC patients.[39]

Additional associations with CSC risk include pregnancy, alcohol use, untreated hypertension, systemic lupus erythematosus, organ transplantation, end-stage renal disease, helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, and possibly antibiotic use.[28][40] Certain other medications, including sildenafil and topiramate, have also been found to potentially increase risk of CSC.[41][42] The use of MEK/ERK inhibitors (such as sorafenib and vemurafenib) has previously been associated with a form of serous maculopathy, but does not have the typical choroidal characteristics on multimodal imaging and may thus be the result of toxicity to the RPE, as the clinical picture typically resolves upon cessation of medication.[43][44] Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) or “ecstasy” has also been linked to a CSC case, but it is unclear whether this is an important risk factor.[45]

A genetic predisposition to CSC has been suggested in 52% of family members of patients with CSC.[46] Weenink and colleagues studied the family members of 27 patients with bilateral CSC and found that in 52% of the families, at least 1 relative was affected.[47] Of the studied family members, 27.5% suffered from chronic CSC in at least 1 eye. However, most CSC cases are diagnosed in patients with no refractive error or with mild hyperopia.

Pathophysiology

RPE abnormalities, while a clinical hallmark of CSC, are now thought to be mostly secondary to underlying choroidal dysfunction, with subsequent breakdown of the RPE outer blood-retina barrier leading to leakage of fluid below the neuroretina. ICGA studies have provided important clues with regard to the pathophysiology of CSC, demonstrating choroidal staining in the form of indistinct hyperfluorescence that is reduced following treatment with photodynamic therapy (PDT), suggesting increased capillary permeability to be the cause of CSC. [10][48][49][50] Indocyanine green videoangiography shows choroidal hyperpermeability, irregular dilation of choroidal veins, and choroidal lobular ischemia.[17][51][52] Prunte and Flammer demonstrated the presence of delayed arterial filling and ischemia, followed by capillary and venous congestion in areas of the choroid affected by CSC, either or both of which could be the mechanism for increased permeability.[16] The location of SRF often correlates with hyperfluorescent abnormalities seen on ICGA, which are believed to reflect vascular hyperpermeability of the choriocapillaris.[53] Furthermore, microscopic evaluation of iatrogenic CSC in monkeys revealed damage and endothelial cell defects of choriocapillaris with overlying degeneration of RPE cells.[54]

Enhanced depth imaging OCT of the choroid showed thickening of the choroid in patients with CSC that normalizes following treatment with PDT, which further supports the role of vascular congestion and elevated hydrostatic pressure.[55][56] Other typical choroidal abnormalities in patients with CSC include dilated veins in Haller’s layer, an elevated choroidal vascularity index (the ratio of luminal to total choroidal area), and thinning of the choriocapillaris. This condition is also referred to ‘pachychoroid’, and encompasses a spectrum of phenotypes.[57][58][59] FAF studies show that in acute CSC, there is increased autofluorescence in the area of leakage suggesting elevated metabolic activity of the RPE.[60] However, in chronic CSC, there is decreased or absent autofluorescence suggesting reduced metabolic activity of the RPE and secondary RPE damage. Hyper- or hypofluorescence on FAF is attributed to changes in subretinal and RPE lipofuscin content.

While pathophysiologic anatomy has been shown, the actual cause is still in speculation. The ‘pachychoroid’ spectrum of phenotypes is associated with signs of choroidal venous overload, which has been proposed by Spaide and colleagues as a significant factor in the pathophysiology of CSC.[61][52] Choroidal venous overload has been linked to venous outflow abnormalities, delayed choroidal filling, and intervortex venous anastomoses.[62][63] Such abnormalities in the venous drainage system suggest that an imbalance in choroidal venous outflow might be intrinsic to CSC.[64] Moreover, increased scleral rigidity and thickness have been associated with congested choroidal outflow and vascular resistance.[65][66][67][68] Recent studies also suggest that the sclera in steroid-induced CSC is significantly thinner than in CSC without steroid use, highlighting the role of the sclera in disease progression.[69] These anatomical abnormalities, presumably in combination with additional factors such as genetic, hormonal, and other exogenous factors, lead to pathologic changes and possible ischemia in the choriocapillaris.[53] The choroidal abnormalities in pachychoroid spectrum diseases such as CSC reflected on ICGA, which generally shows typical indistinct areas of hyperfluorescence in the mid-phase (approximately 10 minutes), that can be focally, multifocally, or diffusely present in the posterior pole of the eye.[51][52]

Active CSC has been correlated with elevated levels of endogenous and exogenous corticosteroids.[70] Intravitreal injections of corticosteroids and aldosterone in rats leads to choroidal enlargement,[71] suggesting that CSC-associated vasculopathy may in part be due to activation of the mineralocorticoid receptor, which has become a target for treatment.[71] [72] [73] Some mechanisms of action of steroids on the choroid and RPE include potentiation of adrenergic hormones,[74] hypertension,[75] [76] and altered ion transport in RPE cells.[77] Glucocorticoids regulate the expression of adrenergic hormones and receptors, and therefore, said hormones may contribute to the pathophysiology of CSC.[15] A study showed that patients with CSC have increased sympathetic activity and decreased parasympathetic activity, based on tests of autonomic activity and reactivity.[14] Other theoretical causes of choriocapillary hyperpermeability and RPE damage include epinephrine;[54][78] ischemia;[79][16] inflammation, from H. pylori infection and other sources; and hormonal factors.[80] Epinephrine and norepinephrine have also been shown to be elevated in patients with active CSC.[70][81]

Foveal attenuation, chronic macular edema, and damage of the foveal photoreceptor layer have been reported as causes of visual loss in CSC. Chronic RPE damage can lead to RPE atrophy, reduced choroidal permeability, and changes in subretinal lipofuscin content, all of which have been observed using ICGA and FAF imaging techniques.[10] Secondary RPE damage manifests as focal lesions or more extensive degeneration, which has been described in terms such as diffuse atrophic RPE alterations (DARA) or diffuse retinal pigment epitheliopathy (DRPE).[82][83]

Diagnosis

History

Typically, patients complain of central vision loss or distortion with a possible central scotoma. Other common complaints include micropsia, hyperopic or myopic shift, and reduced contrast sensitivity and color saturation.[2] Patients are generally healthy; however, CSC may be the initial presenting feature of Cushing’s disease, and the associated symptoms can be subtle.[84] Ophthalmologists should be aware of this association to ensure timely and appropriate referrals. Patients with signs of Cushing’s disease, such as abdominal obesity, stretch marks, muscle weakness, easy bruising, facial rounding, osteoporosis, hypertension, and diabetes, should be referred to an endocrinologist.[37]

Clinical Diagnosis

The classification of CSC remains a subject of ongoing debate within ophthalmology, as no universally accepted system exists. Discrepancies are present among clinicians concerning the distinctions between acute and chronic forms, which are generally based on the duration of SRF and structural changes visible on multimodal imaging.[85] An alternative classification has therefore been proposed that shifts the focus from symptom duration to disease phenotype, integrating multimodal imaging features such as choroidal abnormalities and patterns of retinal pigment epithelium damage, rather than relying on the acute-chronic dichotomy alone.[86] While this framework may better reflect underlying pathophysiology, further prospective validation is required before it can be widely adopted in clinical practice.

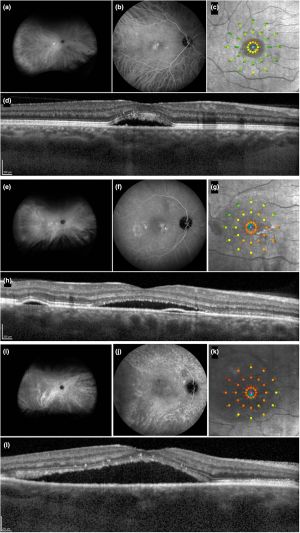

Acute CSC presents with serous neuroretinal detachment in the form of SRF that usually resolves spontaneously within 3-4 months. Typical first-episode acute CSC is characterized by isolated dome-shaped neuroretinal detachment on OCT with limited atrophic RPE changes and minimal leakage points on FA. On refractive examination, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) can range from 20/20 to 20/200. Visual loss can partly be attributed to a hyperopic shift caused by the anterior displacement of the macular photoreceptors. Folk recorded that patients with CSC can have minimal afferent pupillary defects and reduced critical flicker-fusion thresholds, both of which are the first to improve with resolution of the CSC episode.[87] Ophthalmoscopy typically discloses a round or oval serous macular detachment without hemorrhage, with small, yellow subretinal deposits in the area of neurosensory detachment.[88] At times, the subretinal fluid may contain grey-white serofibrinous exudate.[89] A PED may be seen on OCT in up to 63% of eyes,[90] and more visibly on retroillumination. The PED may touch the posterior aspect of the retina, and there is usually a leak at this site.[42] The inner surface of the retina may show a localized depression at this site. In CSC with subretinal fibrin, an area of lucency may denote the site of the leak.

In chronic CSC, SRF typically persists for more than 3-4 months, potentially leading to permanent structural damage in the neuroretina and RPE.[91][92][93][94][95] In contrast to acute CSC, chronic CSC is more likely to recur, and typically shows more widespread RPE abnormalities and extensive leakage on FA. Ophthalmoscopy may show macular RPE mottling with a range from mono- or paucifocal RPE lesions and prominent elevation of the neurosensory retina by clear fluid (typical of cases of recent onset) to shallow detachments overlying large patches of irregularly depigmented RPE. Up to 42% of patients present with signs of bilateral involvement, and even higher percentages when looking at choroidal abnormalities on ICGA, which is common in older patients with chronic CSC and often associated with more severe disease.[22][82][94]

Diagnostic Procedures and Tests

Multimodal imaging modalities, including OCT, FA, ICGA, and FAF are crucial in differentiating CSC from conditions that can mimic CSC.[11][96] OCT can show detailed findings not appreciable on exam such as hyperreflective, fibrinous SRF and small PEDs.[1] Furthermore, OCT can be helpful in following chronic CSC patients to track resolution. Enhanced depth imaging OCT technology has been able to identify choroidal thickening bilaterally, even in patients with unilateral CSC.[55]

FA findings typically include the ink blot appearance (31%), smokestack pattern (12%), and minimally enlarging spot (7%).[97] FA is also used to rule out subretinal neovascularization.[1] The leaking areas on fundus FA can correlate to hyperreflective areas on infrared image in OCT in patients with CSC.[98] ICGA is a key imaging modality to map the underlying choroidal abnormalities, also for potential treatment targeting for example in the case of PDT, especially in recurrent CSC and chronic CSC.[50] Areas of hyperfluorescent leakage on ICGA due to choroidal hyperpermeability are often more extensive than areas identified on FA. On ICGA, CSC is characterized by multiple signs of choroidal venous overload, including asymmetric arterial choroidal filling, dilated choroidal vessels (pachyvessels), asymmetric venous drainage with the presence of choroidal intervortex venous anastomoses, and choroidal vascular hyperpermeability (CVH).[51] In the midphase of ICGA (approximately 10 minutes), CVH typically manifests as focal or diffuse areas of hyperfluorescence, classified as unifocal indistinct signs of hyperpermeability (uni-FISH), multifocal hyperpermeability (multi-FISH), or diffuse indistinct hyperfluorescence (DISH).[52] These CVH patterns correlate with disease severity, chronicity, and functional outcomes including BCVA and macular sensitivity on microperimetry.[99]

FAF at 488 nm provides functional images of the fundus by employing the stimulated emission of light from endogenous fluorophores, the most significant being lipofuscin. In the case of RPE cells, the buildup of lipofuscin is related in large part to the phagocytosis of damaged photoreceptor outer segments and altered molecules retained within lysosomes, which eventually become lipofuscin. RPE alterations associated with current or previous SRF show hyper- or hypofluorescence in affected areas. Moreover, near infrared fundus autofluorescence (NIA) imaging (787 nm) can study the RPE, the choriocapillaris, and choroid, by determining melanin fluorescence.

Recent advancements in the classification of CSC have proposed more refined systems that need additional validation. For example, the Central Serous Chorioretinopathy International Group introduced a multimodal imaging-based classification, suggesting that CSC be divided into simple and complex subtypes.[86] Key criteria for diagnosing CSC include:

- Serous neuroretinal detachment confirmed via OCT, and

- RPE alterations visible on FAF, spectral-domain OCT, or infrared imaging.

Additional criteria for CSC include hyperfluorescent placoid areas on ICGA, focal leaks on FA, or subfoveal choroidal thickness (SFCT) ≥400 μm. The system further divides CSC into subtypes such as primary, recurrent, or resolved CSC, with particular attention to foveal involvement and the presence of outer retinal atrophy.

Natural Progression and Prognosis

Acute CSC prognosis is generally favorable with spontaneous resolution of neurosensory retinal detachment in 84-100% of cases within 6 months and generally good recovery of visual acuity.[2][100] Of note, recurrences of CSC have been documented in up to 50% of patients within 1 year.[35][101][102][103][104] In chronic CSC, visual prognosis is more guarded, with up to 13% of patients experiencing legal blindness after 10 years.[91][105] Beyond visual acuity loss, chronic CSC is associated with a significantly reduced vision-related quality of life across most NEI-VFQ-39 domains compared to healthy controls. . Chronic CSC often leads to macular photoreceptor damage and RPE atrophy, affecting both visual acuity and contrast sensitivity. Limited studies investigating prognostic markers found that outer nuclear layer thickness at the fovea correlates with BCVA in patients with resolved CSC[106] and that total foveal thickness correlates with BCVA in patients with chronic CSC who have symptoms for 21.8 (7-36) months.[107] Severe forms of chronic CSC, particularly those involving bilateral SRF, pose an a higher risk of irreversible visual impairment. For example, cCSC may lead PCRD as a result of cystoid fluid accumulation, resulting in further visual deterioration.[82][108]

Management

Overview of Treatment

The primary aim in treating CSC is to achieve complete SRF resolution to preserve the outer neurosensory retinal layers and restore normal photoreceptor-RPE interaction, as persistent SRF can lead to irreversible damage.[109][110] Depending on whether the presented CSC is acute or chronic, or recurrent, there are different options or modalities to be considered including observation, PDT, argon laser photocoagulation, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injection, and systemic medical treatment. An evidence-based treatment guideline for CSC was proposed by Boon and colleagues, in which it was recommended to defer intervention for up to 3-4 months for acute CSC, as the disease often resolves in 2-3 months.[96][111][112] The guideline further recommends:

- Selective acute CSC cases can be treated with either half-dose or half-fluence PDT, especially for patients requiring rapid vision improvement for professional reasons and functionally monocular patients.[103][113][114][115][116]

- Chronic and recurrent CSC should be treated with half-dose or half-fluence PDT.[96][117]

- Chronic CSC with focal, non-central leakage on FA can be treated with argon laser photocoagulation.

- CSC with concurrent macular neovascularizaion should be treated with half-dose or half-fluence PDT in conjunction with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF compound.[118]

A large RCT comparing half-dose PDT to placebo is still warranted to further confirm its efficacy. It should be noted that PDT may not be available, as in the case of the global verteporfin shortage in 2021 and 2022, or covered by health insurance in some regions.[119][120]

Risk Factor Modification

Eliminating potential risk factors plays a crucial role in improving CSC outcomes, regardless of the subtype. Exogenous steroids of any route (oral, intramuscular, intranasal, etc.) have been strongly linked to an increased risk of CSC, even at doses as low as 10 mg per day. DDiscontinuation of steroids is highly recommended if clinically feasible to help prevent recurrence or worsening of the condition; however, if patients must remain on steroids, reductions in steroid dose have been shown to increase the speed of CSC resolution[93]. Because the eye care provider is typically not the person who prescribed these steroids, it is important to maintain close provider-to-provider communication so that the patient's systemic disease is concurrently managed.

While there are several other risk factors that have been associated with CSC, modification strategies have not yielded consistent results, such as discontinuation of exogenous steroids. Patients with type A personality, which is a non-quantifiable descriptive term, might be addressed by lifestyle modification and stress management, although there is an absence of high-quality data to support this. H. pylori has been linked to CSC;[121] its atherosclerosis-inducing cytotoxins are believed to lead to choroidal vessel damage. Several studies investigated the effects of screening and treating H. pylori in patients with CSC, but resulted in discordant results on SRF reabsorption and VA improvement.[96] Similarly, long-standing hypertension has been associated with CSC; however, treatment with anti-hypertensive agents such as propranolol and metoprolol has yielded no beneficial effects. Eplerenone is not superior to placebo for improving chronic CSC in a clinical trial.[122]

Laser Treatments

Photodynamic therapy

PDT with verteporfin, a photosensitizer that accumulates in vessels and helps target therapy, causes endothelial damage and vascular hypoperfusion to inhibit the choroidal hyperpermeability seen in CSC. Several reports and studies have demonstrated that PDT can be used in chronic CSC patients to decrease SRF and improve BCVA.[123] Bae demonstrated that reduced-fluence PDT was superior to intravitreal ranibizumab in an RCT for improving BCVA and central retinal thickness.[124] Half-dose PDT treatment allowed for faster SRF resolution and decreased recurrence compared to half-fluence PDT in eyes with chronic CSC.[125] Findings from two large RCTs—the PLACE trial and the SPECTRA trial—demonstrated the superiority of half-dose PDT over high-density subthreshold micropulse laser treatment, and the superiority of half-dose PDT over oral eplerenone treatment, respectively.[126][127] The study also showed that foveal half-dose PDT for CSC treatment resulted in significant improvement in integrity of the external limiting membrane and ellipsoid zone, without evidence of foveal atrophy development post treatment, suggesting that half-dose PDT is a safe and effective method of treating foveal-involved CSC.[128]

Concerns about choroidal ischemia and retinal atrophy mainly derived from its use in age-related macular degeneration have been largely unfounded in CSC, which is characterized by a congested, thickened and hyperpermeable choroid. Studies have demonstrated that both full-dose and half-dose PDT can reduce choroidal abnormalities and leakage in CSC, with serious adverse events being very rare, also when applied in a bilaterally in the same session.[129][130] A recent study also demonstrated that standard PDT with chlorin E6 was an effective and safe alternative to the standard PDT with verteporfin (Visudyne) in management of CSC.[131]

Laser photocoagulation

Focal continuous-wave thermal laser photocoagulation (also known as continuous wave laser, focal laser, or conventional laser) has historically been employed to treat extrafoveal leakage in CSC cases. The treatment, traditionally administered via focal argon laser or micropulse diode laser photocoagulation, relies on FA to identify focal targets based on hyperfluorescent leakage sites, generally at adisruption/detachment of the RPE. It is hypothesized that the laser coagulation of these sites allows scarring that reduces leakage and re-attaches the retina. During this process, healthy surrounding RPE cells are able to pump SRF back towards the choroid and expedite healing.

For patients with focal leakage outside the fovea, focal argon laser photocoagulation may be considered. It has been shown to reduce the duration of CSC by up to two months, with complete resolution of RPE detachment and increased speed of improvement of VA. However, the long-term benefits of focal argon laser photocoagulation remain unclear. Several studies showed significantly decreased rates of CSC recurrence in treatment groups vs placebo groups after 9 to 18 months of follow-up. Others have concluded there was no difference in CSC recurrence rates between groups after 1 to 12 years of follow-up. Although focal argon laser photocoagulation may lead to more rapid resorption of SRF and recovery of VA, patients should be made aware of its potential side effects. Because the laser destroys targeted retinal tissue, patients may develop symptomatic scotomas corresponding to these sites. Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and further vision loss can result if Bruch’s membrane is ruptured by the laser, requiring additional therapy. Due to these potential complications, patients treated with focal argon laser photocoagulation should have regular ophthalmology follow-up. Laser photocoagulation is also more problematic in cases with multifocal or diffuse areas of leakage in the macula. The treatment success and long-term outcome has not been compared with the gold standard of PDT in large prospective studies.

Subthreshold micropulse laser photocoagulation

The traditional argon laser is thought to work by activating the RPE cells at the periphery of the laser burn that are affected but not destroyed by thermal energy.[132] Subthreshold micropulse laser (SML), also known as “high density, low-intensity” laser, uses subthreshold energy that selectively targets RPE cells without inducing chorioretinal damage or scarring. This allows exposure to a large area of RPE cells, which then down-regulate cytokine production and inflammation.[132] The laser is applied in pulses in a frequency that allows heat dissipation to prevent structural heat damage to the retina.[133] Unlike conventional laser, SML can be safely applied to the fovea. Fluorescein angiography and indocyanine green (ICG) angiography can be supplemented to determine areas of treatment.[134] Several wavelengths of pulse lasers including green 532 nm laser, yellow 577 nm laser, and infrared 810 nm laser have been used to target different cells in the retina.[135] For example, the 577 nm yellow laser has the highest hemoglobin-to-melanin ratio, making it the best SML for vascular structures. Furthermore, the 577 nm laser allows for more concentrated light with a lower power compared to the 810 nm laser.[136] Several uncontrolled studies have shown the effectiveness of 810 nm and 577 nm SML therapy.[136][137][138] SML avoids the potential side effects of PDT such as RPE atrophy, choroidal neovascularization, choriocapillary ischemia, and transient reduction of macular function.[133] Similar to PDT, there is no visible tissue response during treatment, which is why SML treatment guidelines for optimal laser, energy, and duty cycle parameters is a much-needed area of investigation. In an RCT, chronic CSC patients treated with 810 nm SML showed significantly better BCVA, lack of scotoma, and improved contrast sensitivity compared to patients treated with argon laser photocoagulation.[139] In comparing the anatomic and functional efficacy and safety of PDT vs SML in treating CSC, there are mixed results. A study comparing 577 nm SML with PDT in the treatment of chronic CSC showed a better treatment response in the SML group and greater improvement in central retinal thickness in the SML group.[133] In another randomized controlled clinical trial, half-dose PDT, when compared to high-density SML, showed superior results in treatment of chronic CSC: A significantly higher proportion of patients had complete resolution of SRF and associated functional improvement with half-dose PDT intervention.[140]

Medical Therapy

Anti-corticosteroid therapy

As mineralocorticoid receptor action has been implicated in the pathogenesis of CSC, Zhao and Bousquet treated patients with eplerenone, a mineralocorticoid antagonist, for 5 weeks. They found a significant and rapid improvement of retinal detachment with improvement in mean central macular thickness, subretinal fluid height, and visual acuity that persisted and was evident at 5 months' follow-up.[71][72] Similar studies have supported this potential treatment and have shown greater efficacy in patients with chronic CSC.[72][73] Spironolactone, another anticorticosteroid, has been shown to decrease subretinal fluid, decrease central retinal thickness, and increase BCVA in patients with chronic CSC.[141] A prospective, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study with a crossover design showed a reduction in subretinal fluid and subfoveal choroidal thickness.[142] A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial studying the use of eplerenone for chronic CSC found modest gains in BCVA and improvement in subretinal fluid height (in press).

Mineralocorticoid antagonists may raise serum potassium level, especially in patients with congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Hyperkalemia can manifest as fatigue, muscle weakness, palpitations, and arrhythmias.[143] Prior to starting a medication in this class, reviewing medical history and discussing it with the primary care doctor is recommended. Baseline serum potassium levels and renal function should be established, such as with a basic metabolic panel. Initiation of medication should be postponed or avoided if serum potassium concentration is >5.5 mEq/L, creatinine clearance is <50 mL/min, or serum creatinine is >2 mg/dL in men and >1.8 mg/dL in women.[143] Other anti-corticosteroid treatments have also been studied. Finasteride, a 5a-reductase inhibitor with anti-androgenic properties, was shown to improve central macular thickness (CMT) and subretinal volume in a study of 5 patients, but these findings reversed when the drug was discontinued.[144] Mifepristone, an antiprogesterone and antiglucocorticoid agent, was shown in a study of 16 patients to improve Snellen visual acuity.[145] Rifampin, an antituberculous drug and cytochrome P450 3A4 inducer, accelerates the metabolism of steroids and has been shown to benefit patients with CSC.[146] However, its use may be avoided in countries with high prevalence of tuberculosis, due to the risk of resistance.

In a case study of a patient who had multifocal CSC with persistent SRF for 2 years, treatment with rifampin showed complete resolution of the SRF in 1 month.[146] Side effects of rifampin include orange-colored body fluids, anorexia, and hepatotoxicity.[146]

Melatonin is an endogenous neuromodulator that has been linked to circadian cycles and sleep regulation, aging, and neuroprotection via an antioxidant mechanism.[122] Melatonin also has an inhibitory effect on corticosteroids and has a minimal side effect profile, suggesting it as a possible CSC treatment. A study of 8 patients showed significant improvements in CMT (87.5%) and BCVA (100%) compared to controls.[147] Furthermore, no side effects were observed.

Aspirin

Low-dose aspirin has been explored in treating CSC. Elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI 1), a marker of platelet aggregation, have been linked to steroid use and have been measured in patients with CSC.[148] A prospective study of 113 eyes with CSC showed faster improvement in BCVA compared to controls.[148] However, the use of a historical control group limits the strength of the evidence supporting aspirin as an effective treatment for CSC, and there is no role for aspirin as a first-line treatment for CSC.

Helicobacter pylori treatment

A randomized control trial (RCT) of patients who tested positive for H. pylori studied the effect of the treatment of H. pylori treatment of chronic CSC.[149] This study found that patients treated for H. pylori infection had faster resolution of sub-retinal fluid (9 weeks) versus control (11 weeks) but no change in BCVA. A case series of treated biopsy-positive H. pylori patients showed resolution of SRF in 14 of 15 patients.[150] However, another RCT tested the same hypothesis and found no statistical change in the resolution of SRF and BCVA.[151] Dang and colleagues did find a statistically significant improvement in foveal sensitivity in the H. pylori treatment group. These studies with contradictory results indicate that the current body of evidence does not support H. pylori eradication as a reliable treatment for CSC.

Anti-adrenergic agents

The role of anti-adrenergic therapy for CSC is unclear. A small case series in 1993 described 6 patients with CSC treated with metoprolol, a non-selective beta-blocker, who improved symptomatically and had partial or complete resolution of retinal detachment.[152] Other studies have suggested that both metipranolol (non-selective beta-blocker) and metoprolol tartrate (selective beta-1 blocker) induce remission of CSC.[153][154] In contrast, a randomized controlled double-blind study examining the impact of beta-blockade with metipranolol found no difference in the course of acute CSC between the beta-blocker group and the control group.[155] Although anti-adrenergic agents have been shown to be beneficial in CSC in some studies, further studies are necessary before anti-adrenergic agents can be considered a viable treatment option for CSC.

Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy

The use of anti-VEGF agents is based on the idea that VEGF levels may be elevated due to the choroidal pathology. However, studies have shown that VEGF levels are similar between CSC patients and control patients.[156][157] A meta-analysis of four controlled studies with patients treated with intravitreal bevacizumab (IVB) compared to control showed no improvement in BCVA or CMT at six months.[158] Of note, patients with coexisting macular neovascularization and CSC (confirmed on FA or OCT-angiography) do benefit from anti-VEGF therapy.[159] However, patients with macular neovascularization and/or polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy—an important differential diagnosis for uncomplicated CSC in patients older than 50 years—may benefit from anti-VEGF agents.[96] Intravitreal injection with faricimab, a bispecific antibody targeting both VEGF and Ang-2 pathways, on the other hand, resulted in reduction in macular thickness and reduction in SRF and/or IRF, with associated visual acuity improvement in patients with chronic CSC and longstanding SRF.[160]

Summary

CSC is a multifactorial disease that is hypothesized to occur because of choroidal hyperpermeability and secondary RPE dysfunction leading to serous retinal detachment. While acute CSC can often be managed conservatively for up to 3-4 months, early treatment should be considered for patients who depend on optimal vision as well as to reduce risk of recurrence and progression to chronic CSC. The mainstay of treatment in chronic CSC is currently half-dose (or half-fluence) PDT, offering faster SRF resolution, improved BCVA, and lower recurrence rates compared to other treatments. However, a global shortage of verteporfin in 2021 and 2022 highlighted the need for alternative treatments and better planning to prevent future shortages. Further clinical trials and innovative approaches are required to address the limitations of current CSC treatment options.

Additional Resources

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12. Retina and Vitreous. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2022-2023:215-221.

- Porter D, Gregori NZ. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/central-serous-retinopathy-3. Accessed January 07, 2025.

- Porter D, Vemulakonda GA. Blood Pressure. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/anatomy/blood-pressure-list. Accessed January 07, 2025.

- AAO, Laser Photocoagulation of the Retina and Choroid, 1997, p. 237-240.

- Bousquet E, Beydoun T, Rothschild PR, et al. Spironolactone for Nonresolving Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Study. Retina. 2015 May 26.

- Bousquet E, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism in the treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: a pilot study. Retina. 2013 Nov-Dec; 33(10):2096-102.

- Haimovici R, Koh S, Gagnon DR, et al. Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: a case-control study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:244-9.

- Jampol LM, Weinreb R, Yannuzzi L. Involvement of corticosteroids and catecholamines in the pathogenesis of central serous chorioretinopathy: a rationale for new treatment strategies. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1765-6.

- Karakus SH, Basarir B, Pinarci EY, Kirandi EU, Demirok A. Long-term results of half-dose photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy with contrast sensitivity changes. Eye. 2013;27(5):612-620.

- Lai TY, Chan WM, Li H, et al. Safety enhanced photodynamic therapy with half dose verteporfin for chronic central serous retinopathy: as short term pilot study. Br J Ophthalmology. 2006;90:869-74.

- Nicholson B, Noble J, Forooghian F, Meyerle C. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Update on Pathophysiology and Treatment. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2013;58(2):103-126.

- Piccolino FC, Borgia L. Central serous Chorioretinopathy and indocyanine angiography. Retina. 1994;14:231-42.

- Schaal KB, Hoeh AE, Scheuerle A, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab for treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009 Jul-Aug;19(4):613-7.

- Singh RP, Sears JE, Bedi R, Schachat AP, Ehlers JP, Kaiser PK. Oral eplerenone for the management of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. International Journal of Ophthalmology. 2015;8(2):310-314.

- Taban M, Boyer DS, Thomas EL, Taban M. Chronic central serous Chorioretinopathy: photodynamic therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 2004: 1073-1080.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wang M, Munch IC, Hasler PW, Prünte C, Larsen M. Central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2008;86(2):126-145. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00889.x.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Liew G, Quin G, Gillies M, Fraser-Bell S. Central serous chorioretinopathy: a review of epidemiology and pathophysiology. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013;41(2):201-214. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02848.x.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gass JD. Pathogenesis of disciform detachment of the neuroepithelium. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 63 (Suppl. l) (1967), pp. 1-139

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kitzmann AS, Pulido JS, Diehl NN, Hodge DO, Burke JP. The incidence of central serous chorioretinopathy in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980-2002. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):169-173. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.032.

- ↑ Von Graefe, A. (1866) Ueber zentrale recidivierende Retinitis. Graefe’s Archives for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 12, 211-215.

- ↑ Walsh FB, Sloan LL, Idiopathic Flat Detachment of the Macula, American Journal of Ophthalmology, Volume 19, Issue 3, 1936, Pages 195-208

- ↑ Edwards TS, Priestley BS, Central Angiospastic Retinopathy*, American Journal of Ophthalmology, Volume 57, Issue 6, 1964, Pages 988-996

- ↑ Straatsma BR, Allen RA, Pettit TH. Central serous retinopathy. Trans Pac Coast Otoophthalmol Soc Annu Meet. 1966;47:107-27. PMID: 5955103.

- ↑ Guyer DR, Yannuzzi LA, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Ho A, Orlock D. Digital indocyanine green videoangiography of central serous chorioretinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol., 112 (1994), pp. 1057-1062

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Spaide RF, Hall L, Haas A, Campeas L, Yannuzzi LA, Fisher YL, Guyer DR, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Orlock DA. Indocyanine green videoangiography of older patients with central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina, 16 (1996), pp. 203-213

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 van Dijk EHC & Boon CJF. Serous business: delineating the broad spectrum of diseases with subretinal fluid in the macula. Prog. Retin. Eye Res., 84 (2021), Article 100955

- ↑ Kang HG, Woo SJ, Lee JY, et al. Pathogenic Risk Factors and Associated Outcomes in the Bullous Variant of Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2022;6(10):939-948. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2022.04.015

- ↑ Tsui JC, Carroll RM, Brucker AJ, Kolomeyer AM. Bullous Variant of Central Serous Chorioretinopathy in Goodpasture's Disease - A Case Report and Review of Literature. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Published online December 5, 2023. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000001522

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Tewari HK, Gadia R, Kumar D, Venkatesh P, Garg SP. Sympathetic–Parasympathetic Activity and Reactivity in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Case–Control Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(8):3474-3478. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-1246.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jampol LM, Weinreb R, Yannuzzi L. Involvement of corticosteroids and catecholamines in the pathogenesis of central serous chorioretinopathy: a rationale for new treatment strategies. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(10):1765-1766. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01303-9.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Prunte C, Flammer J. Choroidal Capillary and Venous Congestion in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(1):26-34. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)70531-8.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Giovannini A, Scassellati-Sforzolini B, D’altobrando E, Mariotti C, Rutili T, Tittarelli R. Choroidal Findings In The Course Of Idiopathic Serous Pigment Epithelium Detachment Detected By Indocyanine Green Videoangiography. Retina. 1997;17(4):286-296.

- ↑ Spitznas M. Pathogenesis of central serous retinopathy: A new working hypothesis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1986;224:321-324.

- ↑ Marmor MF. New hypotheses on the pathogenesis and treatment of serous retinal detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988;226(6):548-552. doi:10.1007/BF02169203.

- ↑ Nicholson B, Noble J, Forooghian F, Meyerle C. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Update on Pathophysiology and Treatment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(2):103-126. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.07.004.

- ↑ Gäckle HC, Lang GE, Freissler KA, Lang GK. [Central serous chorioretinopathy. Clinical, fluorescein angiography and demographic aspects]. Ophthalmol Z Dtsch Ophthalmol Ges. 1998;95(8):529-533.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Spaide RF, Campeas L, Haas A, et al. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy in Younger and Older Adults. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(12):2070-2080. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30386-2.

- ↑ Desai UR, Alhalel AA, Campen TJ, Schiffman RM, Edwards PA, Jacobsen GR. Central serous chorioretinopathy in African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(7):553-559.

- ↑ How ACSW, Koh AHC. Angiographic characteristics of acute central serous chorioretinopathy in an Asian population. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35(2):77-79.

- ↑ Garg S, Dada T, Talwar D, Biswas N. Endogenous cortisol profile in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81(11):962-964.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Carvalho-Recchia CA, Yannuzzi LA, Negrao S, Spaide RF, Freund KB, Rodriguez-Coleman H, Lenharo M, Iida T. Corticosteroids and central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology, 109 (2002), pp. 1834-1837

- ↑ Bouzas EA, Karadimas P, Pournaras CJ. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy and Glucocorticoids. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(5):431-448. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00338-7.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Haimovici R, Koh S, Gagnon DR, Lehrfeld T, Wellik S. Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: A case–control study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(2):244-249. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.024.

- ↑ Tripathy K. Is Helicobacter pylori the culprit behind central serous chorioretinopathy? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 Oct;254(10):2069-2070. Epub 2016 Jun 30. PubMed PMID: 27364118.

- ↑ Rim TH, Kim HS, Kwak J, Lee JS, Kim DW, Kim SS. Association of corticosteroid use with incidence of central serous chorioretinopathy in South Korea. JAMA Ophthalmol., 136 (2018), pp. 1164-1169

- ↑ Tsai DC, Chen SJ, Huang CC, Chou P, Chung CM, Chan WL, Huang PH, Lin SJ, Chen JW, Chen TJ, Leu HB. Risk of central serous chorioretinopathy in adults prescribed oral corticosteroids: a population-based study in Taiwan. Retina, 34 (2014), pp. 1867-1874

- ↑ Liu B, Deng T, Zhang J. Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Retina, 36 (2016), pp. 9-19

- ↑ Zhou M, Bakri SJ, Pershing S. Risk factors for incident central serous retinopathy: case-control analysis of a us national managed care population. Br. J. Ophthalmol., 103 (2019), pp. 1784-1788

- ↑ Yavaş GF, Küsbeci T, Kaşikci M, et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Patients with Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39(1):88-92. doi:10.3109/02713683.2013.824986.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Fok ACT, Chan PPM, Lam DSC, Lai TYY. Risk Factors for Recurrence of Serous Macular Detachment in Untreated Patients with Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;46(3):160-163. doi:10.1159/000324599.

- ↑ Yannuzzi LA. Type-A behavior and central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 1987 Summer;7(2):111-31. doi: 10.1097/00006982-198700720-00009. PMID: 3306853.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Brinks J, van Haalen FM, van Rijssen TJ et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy in active endogenous Cushing’s syndrome. Sci Rep 11, 2748 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82536-2

- ↑ Bouzas EA, Scott MH, Mastorakos G, Chrousos GP, Kaiser-Kupfer MI. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy in Endogenous Hypercortisolism. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(9):1229–1233. doi:10.1001/archopht.1993.01090090081024

- ↑ van Haalen FM, van Dijk EHC, Andela CD, Dijkman G, Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Boon CJF. Maladaptive personality traits, psychological morbidity and coping strategies in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol., 97 (2019), pp. e572-e579

- ↑ Cotticelli L, Borrelli M, D’Alessio AC, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy and Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;Vol. 16(2):274-278.

- ↑ Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy Associated With Sildenafil: Retina. 2008;28(4):606-609. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e31815ec2c8.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Mazumdar S, Tripathy K, Sarma B, Agarwal N. Acquired myopia followed by acquired hyperopia due to serous neurosensory retinal detachment following topiramate intake. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2019 Jan;29(1):NP21-NP24. doi: 10.1177/1120672118797286. Epub 2018 Sep 3. PMID: 30175623.

- ↑ van Dijk EHC, van Herpen CML, Marinkovic M, Haanen JBAG, Amundson D, Luyten GPM, Jager MJ, Kapiteijn EHW, Keunen JEE, Adamus G, Boon CJF. Serous retinopathy associated with mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibition (binimetinib) for metastatic cutaneous and uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(9):1907–1916. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.05.027

- ↑ van Dijk EHC; Duits, Danique EM; Versluis M; Luyten GPM; Bergen, AAB; Kapiteijn, EW; de Lange MJ; Boon CJF; van der Velden PA. Loss of MAPK Pathway Activation in Post-Mitotic Retinal Cells as Mechanism in MEK Inhibition-Related Retinopathy in Cancer Patients. Medicine 95(18):p e3457, May 2016. | DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003457

- ↑ Hassan L, Carvalho C, Yannuzzi LA, Iida T, NegrÃo S. Central serous chorioretinopathy in a patient using methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) or “ecstasy.” Retina. 2001;21(5):559–561.

- ↑ van Dijk EHC, Schellevis RL, Breukink MB, Mohabati D, Dijkman G, Keunen JEE, Yzer S, den Hollander AI, Hoyng CB, de Jong EK, Boon CJF. Familial central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2019 Feb;39(2):398-407. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001966. PMID: 29190234.

- ↑ Weenink AC, Borsje RA, Oosterhuis JA. Familial chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol J Int Ophtalmol Int J Ophthalmol Z Für Augenheilkd. 2001;215(3):183-187. doi:50855.

- ↑ Piccolino FC, Borgia L. Central serous chorioretinopathy and indocyanine green angiography. Retina. 1994;14(3):231–242.

- ↑ Hayashi K, Hasegawa Y, Tokoro T. Indocyanine green angiography of central serous chorioretinopathy. Int. Ophthalmol., 9 (1986), pp. 37-41

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 van Rijssen TJ, Hahn LC, van Dijk EHC, Tsonaka R, Scholz P, Breukink MB, Blanco-Garavito R, Souied EH, Keunen JEE, MacLaren RE, Querques G, Fauser S, Downes SM, Hoyng CB, Boon CJF. Response of choroidal abnormalities to photodynamic therapy versus micropulse laser in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: PLACE trial report no. 4. Retina, 41 (2021), pp. 2122-2131

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Pauleikhoff LJB, Diederen RMH, Chang-Wolf JM, Moll AC, Schlingemann RO, van Dijk EHC, Boon CJF. Choroidal Vascular Changes on Ultrawidefield Indocyanine Green Angiography in Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: CERTAIN Study Report 1. Ophthalmol Retina. 2024 Mar;8(3):254-263. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2023.10.007. Epub 2023 Oct 13. PMID: 37839547.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Pauleikhoff LJB, Diederen RMH, Chang-Wolf JM, Moll AC, Schlingemann RO, van Dijk EHC, Boon CJF. Choroidal hyperpermeability patterns correlate with disease severity in central serous chorioretinopathy: CERTAIN study report 2. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024 Sep;102(6):e946-e955. doi: 10.1111/aos.16679. Epub 2024 Apr 1. PMID: 38561630.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Teussink MM, Breukink MB, van Grinsven MJ, Hoyng CB, Klevering BJ, Boon CJ, de Jong EK, Theelen T. OCT Angiography Compared to Fluorescein and Indocyanine Green Angiography in Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015 Aug;56(9):5229-37. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17140. PMID: 26244299.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Yoshioka H, Katsume Y. Experimental central serous chorioretinopathy. III: ultrastructural findings. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1981;26(4):397-409.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Imamura Y, Fujiwara T, Margolis R, Spaide RF. Enhanced Depth Imaging Optical Coherence Tomography Of The Choroid In Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Retina. 2009;29(10):1469-1473. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181be0a83.

- ↑ Maruko I, Iida T, Sugano Y, Ojima A, Ogasawara M, Spaide RF. Subfoveal choroidal thickness after treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology, 117 (2010), pp. 1792-1799

- ↑ Cheung CMG, Dansingani KK, Koizumi H, Lai TYY, Sivaprasad S, Boon CJF, Van Dijk EHC, Chhablani J, Lee WK, Freund KB. Pachychoroid disease: review and update. Eye (Lond). 2025 Apr;39(5):819-834. doi: 10.1038/s41433-024-03253-4. Epub 2024 Aug 3. PMID: 39095470; PMCID: PMC11933466.

- ↑ Agrawal R, Chhablani J, Tan KA, Shah S, Sarvaiya C, Banker A. Choroidal vascularity index in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina, 36 (2016), pp. 1646-1651

- ↑ Cardillo Piccolino F, Lupidi M, Cagini C, Fruttini D, Nicolo M, Eandi CM, Tito S. Choroidal vascular reactivity in central serous chorioretinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci., 59 (2018), pp. 3897-3905

- ↑ von Rückmann A, Fitzke FW, Fan J, Halfyard A, Bird AC. Abnormalities of fundus autofluorescence in central serous retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(6):780-786. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01428-9.

- ↑ Spaide RF, Cheung CMG, Matsumoto H, Kishi S, Boon CJF, van Dijk EHC, Mauget-Faysse M, Behar-Cohen F, Hartnett ME, Sivaprasad S, Iida T, Brown DM, Chhablani J, Maloca PM. Venous overload choroidopathy: a hypothetical framework for central serous chorioretinopathy and allied disorders. Prog. Retin. Eye Res., 86 (2022), Article 100973

- ↑ Hiroe T, Kishi S. Dilatation of asymmetric vortex vein in central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol. Retina, 2 (2018), pp. 152-161

- ↑ Kishi S, Matsumoto H, Sonoda S, Hiroe T, Sakamoto T, Akiyama H. Geographic filling delay of the choriocapillaris in the region of dilated asymmetric vortex veins in central serous chorioretinopathy. PloS One, 13 (2018), Article e0206646

- ↑ R.F. Spaide. Choroidal blood flow: review and potential explanation for the choroidal venous anatomy including the vortex vein system. Retina, 40 (2020), pp. 1851-1864

- ↑ Fernandez-Vigo JI, Moreno-Morillo FJ, Shi H, Ly-Yang F, Burgos-Blasco B, Guemes-Villahoz N, Donate-Lopez J, Garcia-Feijoo J. Assessment of the anterior scleral thickness in central serous chorioretinopathy patients by optical coherence tomography. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol., 65 (2021), pp. 769-776

- ↑ Imanaga N, Terao N, Nakamine S, Tamashiro T, Wakugawa S, Sawaguchi K, Koizumi H. Scleral thickness in central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5:285–291.

- ↑

Lee YJ, Lee YJ, Lee JY, Lee S. A pilot study of scleral thickness in central serous chorioretinopathy using anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5872.

- ↑

Venkatesh P, Takkar B, Temkar S. Clinical manifestations of pachychoroid may be secondary to pachysclera and increased scleral rigidity. Med Hypotheses. 2018;113:72–73.

- ↑ Sawaguchi S, Terao N, Imanaga N, Wakugawa S, Tamashiro T, Yamauchi Y, Koizumi H. Scleral thickness in steroid-induced central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol. Sci., 2 (2022), Article 100124

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Haimovici R, Rumelt S, Melby J. Endocrine abnormalities in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(4):698-703. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01975-9.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Zhao M, Célérier I, Bousquet E, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor is involved in rat and human ocular chorioretinopathy. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(7):2672-2679. doi:10.1172/JCI61427.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Bousquet E, Beydoun T, Zhao M, Hassan L, Offret O, Behar-Cohen F. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism In The Treatment Of Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Pilot Study. Retina. 2013;33(10):2096-2102. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e318297a07a.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Chin EK, Almeida DR, Roybal CN, et al. Oral mineralocorticoid antagonists for recalcitrant central serous chorioretinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ. 2015;9:1449-1456. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S86778.

- ↑ Barnes PJ. Corticosteroid effects on cell signalling. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(2):413-426. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00125404.

- ↑ Tittl MK, Spaide RF, Wong D, et al. Systemic findings associated with central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(1):63-68.

- ↑ Yang S, Zhang L. Glucocorticoids and vascular reactivity. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2004;2(1):1-12.

- ↑ Arndt C, Sari A, Ferre M, et al. Electrophysiological effects of corticosteroids on the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(2):472-475.

- ↑ Sibayan SA, Kobuch K, Spiegel D, et al. Epinephrine, but not dexamethasone, induces apoptosis in retinal pigment epithelium cells in vitro: possible implications on the pathogenesis of central serous chorioretinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Für Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238(6):515-519.

- ↑ Yoshioka H, Katsume Y. Experimental central serous chorioretinopathy. III: ultrastructural findings. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1981;26(4):397-409.

- ↑ Gemenetzi M, De Salvo G, Lotery AJ. Central serous chorioretinopathy: an update on pathogenesis and treatment. Eye Lond Engl. 2010;24(12):1743-1756. doi:10.1038/eye.2010.130.

- ↑ Jinghua S, Junfeng T, Zhitao W, Hong Y, Xuefei Z, Lingli L. Effect of catecholamine on central serous chorioretinopathy. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2003;23(3):313-316. doi:10.1007/BF02829525.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Mohabati D, van Rijssen TJ, van Dijk EH, Luyten GP, Missotten TO, Hoyng CB, Yzer S, Boon CJ. Clinical characteristics and long-term visual outcome of severe phenotypes of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018 Jun 7;12:1061-1070. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S160956. PMID: 29922035; PMCID: PMC5995302.

- ↑ Polak BC, Baarsma GS, Snyers B. Diffuse retinal pigment epitheliopathy complicating systemic corticosteroid treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995 Oct;79(10):922-5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.10.922. PMID: 7488581; PMCID: PMC505294.

- ↑ van Dijk EH, Dijkman G, Biermasz NR, et al. Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy as a presenting symptom of Cushing syndrome. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016 Aug;26(5):442-448. DOI: 10.5301/ejo.5000790. PMID: 27135093.

- ↑ Singh SR, Matet A, van Dijk EHC, Daruich A, Fauser S, Yzer S, Peiretti E, Sivaprasad S, Lotery AJ, Boon CJF, Behar-Cohen F, Freund KB, Chhablani J. Discrepancy in current central serous chorioretinopathy classification. Br. J. Ophthalmol., 103 (2019), pp. 737-742

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Chhablani J, Cohen FB; Central Serous Chorioretinopathy International Group. Multimodal Imaging-Based Central Serous Chorioretinopathy Classification. Ophthalmol Retina. 2020 Nov;4(11):1043-1046. PMID: 33131671. DOI: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.07.026

- ↑ Folk JC, Thompson HS, Han DP, Brown CK. Visual function abnormalities in central serous retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol Chic Ill 1960. 1984;102(9):1299-1302.

- ↑ Colucciello M. Update on Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Retinal Physician. http://www.retinalphysician.com/articleviewer.aspx?articleID=107233. Published July 1, 2012. Accessed October 27, 2016.

- ↑ Hussain D, Gass JD. Idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1998;46(3):131.

- ↑ Mitarai K, Gomi F, Tano Y. Three-dimensional optical coherence tomographic findings in central serous chorioretinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Für Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(11):1415-1420. doi:10.1007/s00417-006-0277-7.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Breukink MB, Dingemans AJ, den Hollander AI, Keunen JE, MacLaren RE, Fauser S, Querques G, Hoyng CB, Downes SM, Boon CJ. Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: long-term follow-up and vision-related quality of life. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:39–46.

- ↑ Laatikainen L. Diffuse chronic retinal pigment epitheliopathy and exudative retinal detachment. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1994;72:533–536.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Loo RH, Scott IU, Flynn HW Jr, Gass JD, Murray TG, Lewis ML, Rosenfeld PJ, Smiddy WE. Factors associated with reduced visual acuity during long-term follow-up of patients with idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2002;22:19–24.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Mrejen S, Balaratnasingam C, Kaden TR, Bottini A, Dansingani K, Bhavsar KV, Yannuzzi NA, Patel S, Chen KC, Yu S, Stoffels G, Spaide RF, Freund KB, Yannuzzi LA. Long-term visual outcomes and causes of vision loss in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:576–588.

- ↑ von Winning CH, Oosterhuis JA, Renger-van Dijk AH, Hornstra-Limburg H, Polak BC. Diffuse retinal pigment epitheliopathy. Ophthalmologica. 1982;185:7–14.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 96.3 96.4 Feenstra HMA, van Dijk EHC, Cheung CMG, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy: An evidence-based treatment guideline. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 2024;101:101236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2024.101236

- ↑ Yamada K, Hayasaka S, Setogawa T. Fluorescein-angiographic patterns in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy at the initial visit. Ophthalmol J Int Ophtalmol Int J Ophthalmol Z Für Augenheilkd. 1992;205(2):69-76.

- ↑ Bilgic A, March de Ribot F, Ghia P, Sudhalkar A, Kodjikian L, Tyagi M, Sudhalkar A. Correlation in acute CSCR between hyperreflectivity on the infrared image in optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020 Sep 9:1120672120957600. doi: 10.1177/1120672120957600.

- ↑ Chang-Wolf JM, Pauleikhoff LJB, Ruiters C, Moll AC, Schlingemann RO, van Dijk EHC, Diederen RMH, Boon CJF. Choroidal vascular hyperpermeability patterns in central serous chorioretinopathy correlate with microperimetry: CERTAIN study report 4. Acta Ophthalmol. 2025 Sep 17. doi: 10.1111/aos.17588. PMID: 40960367

- ↑ Klein ML, Van Buskirk EM, Friedman E, Gragoudas E, Chandra S. Experience with nontreatment of central serous choroidopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;91:247–250.

- ↑ Aggio FB, Roisman L, Melo GB, Lavinsky D, Cardillo JA, Farah ME. Clinical Factors Related To Visual Outcome In Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Retina. 2010;30(7):1128-1134. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cdf381.

- ↑ Ficker L, Vafidis G, While A, Leaver P. Long-term follow-up of a prospective trial of argon laser photocoagulation in the treatment of central serous retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:829–834.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Mohabati D, Boon CJF, Yzer S. Risk of recurrence and transition to chronic disease in acute central serous chorioretinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:1165–1175.

- ↑ Yap EY, Robertson DM. The long-term outcome of central serous chorioretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:689–692.

- ↑ Gilbert CM, Owens SL, Smith PD, Fine SL. Long-term follow-up of central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68(11):815.

- ↑ Matsumoto H, Sato T, Kishi S. Outer nuclear layer thickness at the fovea determines visual outcomes in resolved central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(1):105-110.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2009.01.018.

- ↑ Furuta M, Iida T, Kishi S. Foveal thickness can predict visual outcome in patients with persistent central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol J Int Ophtalmol Int J Ophthalmol Z Für Augenheilkd. 2009;223(1):28-31. doi:10.1159/000161880.

- ↑ Mohabati, DMD, Hoyng CB, Yzer S, Boon CJF. Clinical characteristics and outcome of posterior cystoid macular degeneration in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 40(9):p 1742-1750, September 2020. | DOI: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002683

- ↑ Haga F, Maruko R, Sato C, Kataoka K, Ito Y, Terasaki H. Long-term prognostic factors of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy after half-dose photodynamic therapy: a 3-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181479.

- ↑ van Rijssen TJ, Mohabati D, Dijkman G, Theelen T, de Jong EK, van Dijk EHC, Boon CJF. Correlation between redefined optical coherence tomography parameters and best-corrected visual acuity in non-resolving central serous chorioretinopathy treated with half-dose photodynamic therapy. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202549.

- ↑ Kim KS, Lee WK, Lee SB. Half-dose photodynamic therapy targeting the leakage point on fluorescein angiography in acute central serous chorioretinopathy: a pilot study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:366–373.e1.

- ↑ Missotten TO, Hoddenbach JG, Eenhorst CA, van den Born LI, Martinez Ciriano JP, Wubbels RJ. A randomized clinical trial comparing prompt photodynamic therapy with 3 months observation in patients with acute central serous chorioretinopathy with central macular leakage. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31:1248–1253.

- ↑ Lu HQ, Wang EQ, Zhang T, Chen YX. Photodynamic therapy and anti–vascular endothelial growth factor for acute central serous chorioretinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye (Lond). 2016;30:15–22.

- ↑ Ober MD, Yannuzzi LA, Do DV, Spaide RF, Bressler NM, Jampol LM, Angelilli A, Eandi CM, Lyon AT. Photodynamic therapy for focal retinal pigment epithelial leaks secondary to central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:2088–2094.

- ↑ Tsai MJ, Hsieh YT. Half-time photodynamic therapy for central serous chorioretinopathy. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91:1140–1145.

- ↑ Chan WM, Lai TY, Lai RY, Liu DT, Lam DS. Half-dose verteporfin photodynamic therapy for acute central serous chorioretinopathy: one-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmology. 2008 Oct;115(10):1756-65. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.04.014. Epub 2008 Jun 5. PMID: 18538401.

- ↑ van Rijssen TJ, van Dijk EHC, Scholz P, Breukink MB, Blanco-Garavito R, Souied EH, Keunen JEE, MacLaren RE, Querques G, Fauser S, Downes SM, Hoyng CB, Boon CJF. Focal and Diffuse Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy Treated With Half-Dose Photodynamic Therapy or Subthreshold Micropulse Laser: PLACE Trial Report No. 3. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019 Sep;205:1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.03.025. Epub 2019 Apr 3. PMID: 30951686.

- ↑ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38301969/

- ↑ Sirks MJ, van Dijk EHC, Rosenberg N, Hollak CEM, Aslanis S, Cheung CMG, Chowers I, Eandi CM, Freund KB, Holz FG, Kaiser PK, Lotery AJ, Ohno-Matsui K, Querques G, Subhi Y, Tadayoni R, Wykoff CC, Zur D, Diederen RMH, Boon CJF and Schlingemann RO (2022), Clinical impact of the worldwide shortage of verteporfin (Visudyne®) on ophthalmic care. Acta Ophthalmol, 100: e1522-e1532. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15148

- ↑ Sirks MJ, Subhi Y, Rosenberg N, Hollak CEM, Boon CJF, Diederen RMH, Yzer S, Ossewaarde-van Norel J, de Jong-Hesse Y, Schlingemann RO, Moss RJ, van Dijk EHC. Perspectives and Update on the Global Shortage of Verteporfin (Visudyne®). Ophthalmol Ther. 2024 Jul;13(7):1821-1831. doi: 10.1007/s40123-024-00952-9. Epub 2024 May 16. PMID: 38753294; PMCID: PMC11178716.

- ↑ Rahbani-Nobar MB, Javadzadeh A, Ghojazadeh L, Rafeey M, Ghorbanihaghjo A. The effect of Helicobacter pylori treatment on remission of idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy. Mol Vis. 2011;17:99-103.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Lotery A, Sivaprasad S, O'Connell A, Harris RA, Culliford L, Ellis L, Cree A, Madhusudhan S, Behar-Cohen F, Chakravarthy U, Peto T, Rogers CA, Reeves BC; VICI trial investigators. Eplerenone for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy in patients with active, previously untreated disease for more than 4 months (VICI): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Jan 25;395(10220):294-303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32981-2. PMID: 31982075.

- ↑ Ruiz-Moreno JM, Lugo FL, Armadá F, et al. Photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2010;88(3):371-376. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01408.x.

- ↑ Bae SH, Heo J, Kim C, et al. Low-Fluence Photodynamic Therapy versus Ranibizumab for Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: One-Year Results of a Randomized Trial. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(2):558-565. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.024.

- ↑ Nicoló M, Eandi CM, Alovisi C, et al. Half-Fluence Versus Half-Dose Photodynamic Therapy in Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(5):1033-1037.e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2014.01.022.

- ↑ van Dijk EHC, Fauser S, Breukink MB, Blanco-Garavito R, Groenewoud JMM, Keunen JEE, Peters PJH, Dijkman G, Souied EH, MacLaren RE, Querques G, Downes SM, Hoyng CB, Boon CJF. Half-Dose Photodynamic Therapy versus High-Density Subthreshold Micropulse Laser Treatment in Patients with Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: The PLACE Trial. Ophthalmology. 2018 Oct;125(10):1547-1555. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.021. Epub 2018 Jun 14. PMID: 29776672.

- ↑ van Rijssen TJ, van Dijk EHC, Tsonaka R, Feenstra HMA, Dijkman G, Peters PJH, Diederen RMH, Hoyng CB, Schlingemann RO, Boon CJF. Half-Dose Photodynamic Therapy Versus Eplerenone in Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (SPECTRA): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022 Jan;233:101-110. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.06.020. Epub 2021 Jun 29. PMID: 34214454.

- ↑ Feenstra HMA, Diederen RMH, Lamme MJCM, Tsonaka R, Fauser S, Yzer S, van Rijssen T, Gkika T, Downes SM, Schlingemann RO, Hoyng CB, van Dijk EHC, Boon CJF. Increasing evidence for the safety of fovea-involving half-dose photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2023 Mar 1;43(3):379-388. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003686. Epub 2023 Jan 2. PMID: 36727801; PMCID: PMC9935620.

- ↑ Pinto C, Sousa K, Oliveira E, Mendonça L, Gentil R, Queirós L, Falcão M. Foveal and Extrafoveal Effects of Half-Dose Photodynamic Therapy in Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Cohort Study. Semin Ophthalmol. 2022 Feb 17;37(2):153-157. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2021.1931357. Epub 2021 May 23. PMID: 34027797.

- ↑ Pauleikhoff LJB, Diederen RMH, Feenstra HMA, Schlingemann RO, van Dijk EHC, Boon CJF. Single-session bilateral reduced-settings photodynamic therapy for bilateral chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2023 Aug 1;43(8):1356-1363. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003807. Epub 2023 Jun 9. PMID: 37307569; PMCID: PMC10627544.

- ↑ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38484089/

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 Luttrull J, Dorin G. Subthreshold Diode Micropulse Laser Photocoagulation (SDM) as Invisible Retinal Phototherapy for Diabetic Macular Edema: A Review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2012;8(4):274-284.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 133.2 Scholz P, Altay L, Fauser S. Comparison of subthreshold micropulse laser (577 nm) treatment and half-dose photodynamic therapy in patients with chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Eye Lond Engl. 2016;30(10):1371-1377. doi:10.1038/eye.2016.142.

- ↑ Ricci F, Missiroli F, Regine F, Grossi M, Dorin G. Indocyanine green enhanced subthreshold diode-laser micropulse photocoagulation treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;247(5):597-607. doi:10.1007/s00417-008-1014-1.

- ↑ Yadav NK, Jayadev C, Rajendran A, Nagpal M. Recent developments in retinal lasers and delivery systems. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(1):50. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.126179.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 Yadav NK, Jayadev C, Mohan A, et al. Subthreshold micropulse yellow laser (577 nm) in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: safety profile and treatment outcome. Eye. 2015;29(2):258-265. doi:10.1038/eye.2014.315.

- ↑ Chen S-N, Hwang J-F, Tseng L-F, Lin C-J. Subthreshold Diode Micropulse Photocoagulation for the Treatment of Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy with Juxtafoveal Leakage. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(12):2229-2234. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.08.026.

- ↑ Malik KJ, Sampat KM, Mansouri A, Steiner JN, Glaser BM. Low-Intensity/High-Density Subthreshold Micropulse Diode Laser For Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Retina. 2015;35(3):532-536. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000285.

- ↑ Verma L, Sinha R, Venkatesh P, Tewari H. Comparative evaluation of diode laser versus argon laser photocoagulation in patients with central serous retinopathy: A pilot, randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN84128484]. BMC Ophthalmol. 2004;4(1). doi:10.1186/1471-2415-4-15.

- ↑ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29776672/

- ↑ Herold T, Prause K, Wolf A, Mayer W, Ulbig M. Spironolactone in the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy–a case series. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(12):1985–1991.

- ↑ Bousquet E, Beydoun T, Rothschild P-R, et al. Spironolactone for nonresolving central serous chorioretinopathy: a randomized controlled crossover study. Retina. 2015;35(12):2505–2515.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 Rahimy E, Pitcher J, Fineman M, Hsu J. Oral Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of CSC: Long-term CSC can be treated orally. Retinal Physician. http://www.retinalphysician.com/issues/2016/september-2016/oral-mineralocorticoid-receptor-antagonists-for-th. Published September 1, 2016. Accessed March 3, 2017.

- ↑ Forooghian F, Meleth AD, Cukras C, Chew EY, Wong WT, Meyerle CB. Finasteride for Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Retina Phila Pa. 2011;31(4):766-771. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181f04a35.

- ↑ Nielsen JS, Jampol LM. Oral Mifepristone For Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Retina. 2011;31(9):1928-1936. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821c3ef6.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 146.2 Steinle NC, Gupta N, Yuan A, Singh RP. Oral rifampin utilisation for the treatment of chronic multifocal central serous retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(1):10-13. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300183.

- ↑ Gramajo AL, Marquez GE, Torres VE, Juárez CP, Rosenstein RE, Luna JD. Therapeutic benefit of melatonin in refractory central serous chorioretinopathy. Eye. 2015;29(8):1036-1045. doi:10.1038/eye.2015.104.

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 Caccavale A, Romanazzi F, Imparato M, Negri A, Morano A, Ferentini F. Low-dose aspirin as treatment for central serous chorioretinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ. 2010;4:899.

- ↑ Rahbani-Nobar MB, Javadzadeh A, Ghojazadeh L, Rafeey M, Ghorbanihaghjo A. The effect of Helicobacter pylori treatment on remission of idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy. Mol Vis. 2011;17:99-103.

- ↑ Casella AMB, Berbel RF, Bressanim GL, Malaguido MR, Cardillo JA. Helicobacter pylori as a potential target for the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy. Clinics. 2012;67(9):1047. doi:10.6061/clinics/2012(09)11.

- ↑ Dang Y, Mu Y, Zhao M, Li L, Guo Y, Zhu Y. The effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. September 2013:355. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S50407.

- ↑ Avci R, Deutman AF. Treatment of central serous choroidopathy with the Beta-blockers metoprolol. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1993;202 (3:199-205.

- ↑ Fabianová J, Porubská M, Cepilová Z. Central serous chorioretinopathy--treatment with beta blockers. Ceska Slov Oftalmol Cas Ceske Oftalmol Spolecnosti Slov Oftalmol Spolecnosti. 1998;54(6):401-404.

- ↑ Chrapek O, Spacková K, Rehák J. Treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy with beta blockers. Ceska Slov Oftalmol Cas Ceske Oftalmol Spolecnosti Slov Oftalmol Spolecnosti. 2002;58(6):382-386.

- ↑ Chrapek O, Jirkova B, Kandrnal V, Rehak J, Sin M. Treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy with beta-blocker metipranolol. Biomed Pap. March 2013. doi:10.5507/bp.2013.015.

- ↑ Lim JW, Kim MU, Shin M-C. Aqueous Humor And Plasma Levels Of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor And Interleukin-8 In Patients With Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Retina. 2010;30(9):1465-1471. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181d8e7fe.

- ↑ Shin MC, Lim JW. Concentration of Cytokines in the Aqueous Humor of Patietns with Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2011;31(9):1937-1943. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820a6a17.

- ↑ Chung Y-R, Seo EJ, Lew HM, Lee KH. Lack of positive effect of intravitreal bevacizumab in central serous chorioretinopathy: meta-analysis and review. Eye. 2013;27(12):1339-1346. doi:10.1038/eye.2013.236.

- ↑ Chan W-M, Lai TYY, Liu DTL, Lam DSC. Intravitreal Bevacizumab (Avastin) for Choroidal Neovascularization Secondary to Central Serous Chorioretinopathy, Secondary to Punctate Inner Choroidopathy, or of Idiopathic Origin. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(6):977-983.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.039.

- ↑ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39233019/