Optical Coherence Tomography

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Overview

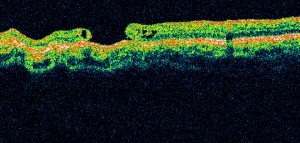

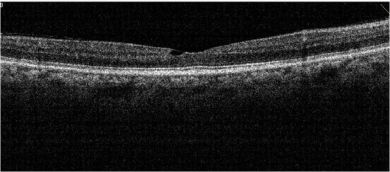

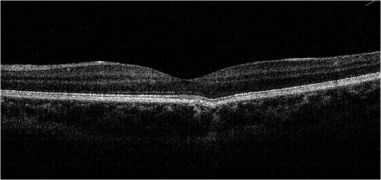

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive diagnostic technique that renders an in vivo cross-sectional view of the retina. OCT utilizes a concept known as interferometry to create a cross-sectional map of the retina that is accurate to within at least 10-15 microns. OCT was first introduced in 1991 by Huang and colleagues[1] and has found many uses outside of ophthalmology, where it has been used to image certain nontransparent tissues. Due to the transparency of the eye (ie, the retina can be viewed through the pupil), OCT has gained wide popularity as an ophthalmic diagnostic tool.

Time Domain vs. Spectral Domain vs. Swept Source

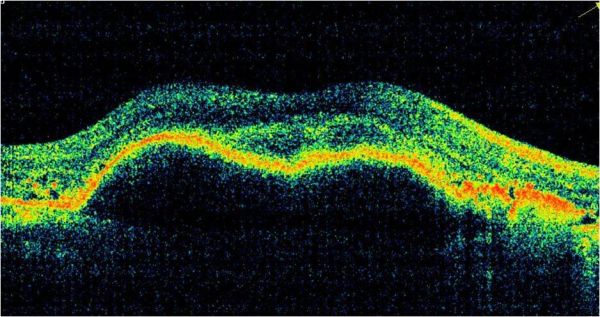

At its inception, OCT images were acquired in a time-domain fashion. Time-domain systems acquire approximately 400 A-scans per second using 6 radial slices oriented 30 degrees apart. Because the slices are 30 degrees apart, care must be taken to avoid missing pathology between the slices.

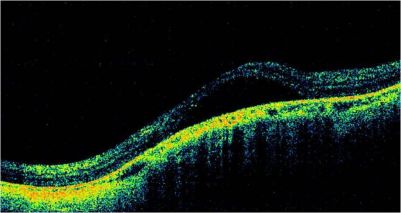

Spectral-domain technology,[2] on the other hand, scans approximately 20,000-40,000 A-scans per second. This increased scan rate and number diminishes the likelihood of motion artifacts, enhances the resolution, and decreases the chance of missing lesions. Spectral-domain systems increase the signal-noise ratio by image averaging multiple B-scans at the same location. Whereas most time-domain OCTs are accurate to 10-15 microns, newer spectral-domain machines may approach 3-micron resolution. Whereas most time-domain OCTs image 6 radial slices, spectral domain systems continuously image a 6 mm area. This diminishes the chance of inadvertently missing pathology. Spectral-domain systems typically operate at 800 nm-870 nm wavelengths, although longer wavelengths of 1050-1060 nm are being developed for deeper penetration in the tissue.

In the late 2000s, the advent of enhanced depth imaging (EDI)[3] allowed for better visualization of the choroid and choroidoscleral interface using the spectral domain system. EDI employed image averaging, which set the zero-delay line (ZDL) adjacent to the choroid.

Swept-source technology,[4] uses a wavelength-sweeping laser and dual-balanced photodetector, allowing for faster acquisition speeds of 100,000-400,000 A-scans per second. This technology uses longer wavelengths of 1050-1060 nm for deeper tissue penetration without the need for EDI. This wavelength provides an axial resolution of about 5.3 µm in tissue compared to the approximately 5 µm axial resolution of the standard 800 nm wavelength of commercial spectral domain devices. The enhanced axial resolution along with the faster scanning speeds, which allow for greater image averaging, improves image quality and the ability to visualize deeper structures in more detail.

Most recently, both spectral domain and swept-source OCT have been used to generate noninvasive, non-dye-based OCT angiography (OCTA)[1] images. In brief, OCT angiography uses motion contrast by comparing the decorrelation signal between multiple B-scans obtained at each retinal cross-section to detect blood flow, employing the principle that theoretically, only circulating erythrocytes within the retinal capillaries should be moving in the retina.

| Time-Domain OCT | Spectral-Domain OCT | Swept-Source OCT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image acquisition | Superluminescent diode (810 nm),

single photon detector, moving mirror |

Broadband superluminescent diode source (840 nm),

an array of detectors, fixed mirror |

Swept-source tunable laser (1050 nm),

single detector |

| Scanning speed

(A-scans per second) |

400 | 27,000 - 70,000 | 1,00,000 - 4,00,000 |

| Axial resolution (μm) | 10 | 5-7 | 5 |

| Transverse resolution (μm) | 20 | 14-20 | 20 |

| Range of imaging | Vitreoretinal interface to RPE | Posterior cortical vitreous to sclera using

enhanced depth imaging (EDI) mode |

Posterior cortical vitreous to sclera

(superior to SD-OCT with EDI) |

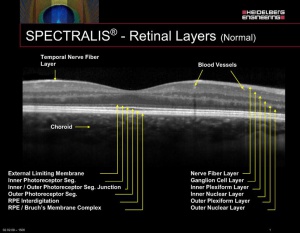

International Nomenclature for OCT [6] suggested the terms band, layer, and zone for the layers of the retina

- The term band refers to the three-dimensional structure of the retinal layers anatomically.

- The term zone describes those regions on OCT whose anatomical correlation is not clearly delineated.

- The RPE (retinal pigment epithelium)/Bruch complex is one of the layers ascribed as a zone, as they are inseparable, owing to the interdigitation of cellular structure or tissue.

Spaide and Curcio showed that "the second band, often attributed to the boundary between inner and outer segments of the photoreceptors, actually aligns with the ellipsoid portion of the inner segments. The third band corresponded to an ensheathment of the cone outer segments by apical processes of the retinal pigment epithelium in a structure known as the contact cylinder.'[7]

Thus, the inner segment-outer segment junction (IS-OS junction) is now called the ellipsoid zone or EZ. The third band is called the interdigitation zone (IZ).[8]

Artifacts on OCT

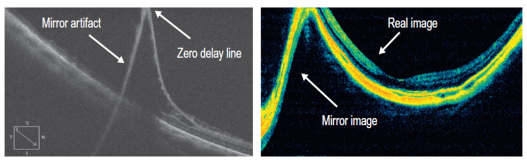

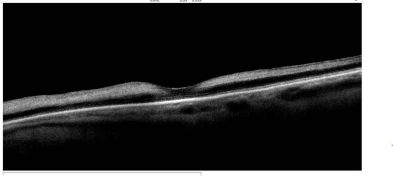

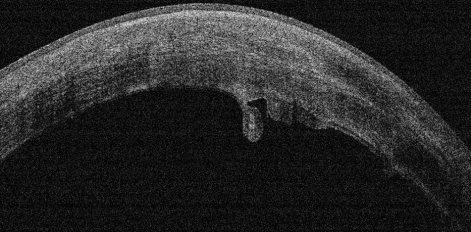

Mirror Artifacts (inverted artifacts):[9]

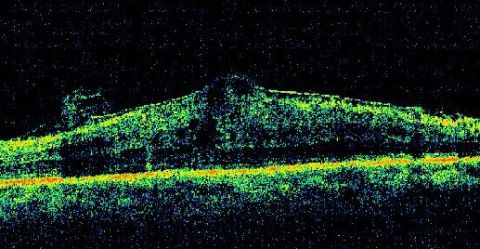

It occurs when the area of interest crosses the zero-delay line and results in an inverted image. In practice, it is especially seen in pathological myopia, retinal detachment, and during the anterior segment OCT.

Vignetting or cut edge artifact:[10]

This occurs when a part of the OCT beam is blocked by the iris or other structures and is characterized by a loss of signal over one side of the image. Some structures may cast an obvious shadow over the retina. These include hemorrhage, pigments, asteroid hyalosis, and vitreous floaters. The shadow by the iris could be avoided by properly dilating the pupil and moving the OCT machine right or left to capture a clearer image.

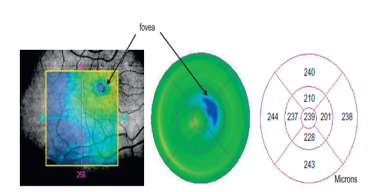

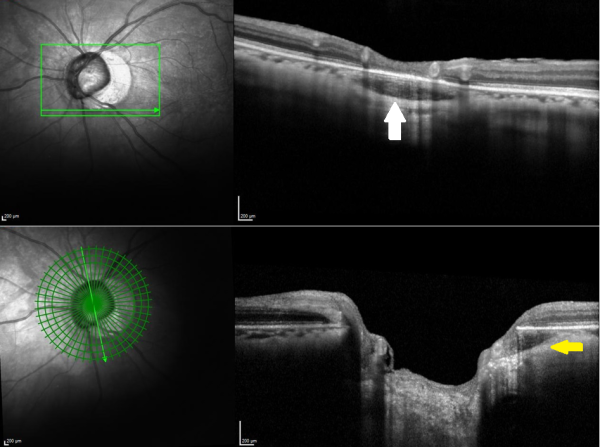

Misalignment or off-center artifact or grid decentration artifact:[11]

This occurs when the fovea is not properly aligned during a volumetric scan. Typically, it is due to the patient's exhibiting poor or eccentric fixation or poor attention. In such cases, the measured central macular thickness (average retinal thickness at the central 1 mm diameter) is wrong, as the map is not centered on the fovea or central macula. The knowledge and skills of the technician or the ophthalmic photographer (who takes the OCT image) are important. They should be trained to identify anatomical landmarks and should be guided by ophthalmologists. Similar misalignment with wrong measurements can happen while measuring central corneal thickness and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. In such cases, the image should be recaptured with proper positioning of the structure of interest.

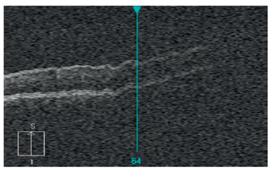

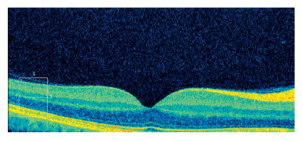

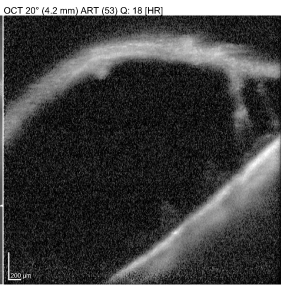

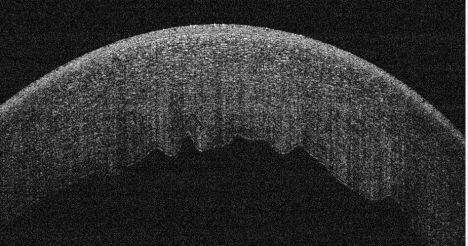

Out-of-Range Error or Out of register artifact:[12]

The area of interest should be at the center of the image. In the provided image, notice that the outer retina/choroidal image is cut off because of the machine's improper positioning during image acquisition. In such cases, the machine needs to be nearer to or farther from the patient for proper capture of the image.

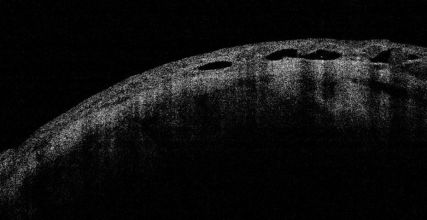

Blink artifact:[12]

Blink artifacts result in partial loss of data due to the momentary blockage of OCT image acquisition during the blink. Blink artifacts are easily recognized as black horizontal bars across the OCT image and macular map.

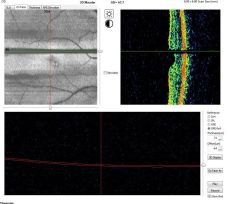

Motion Artifact:[13]

This occurs when the eye movement during OCT scanning leads to distortion or double scanning of the same area. A slab of the image seems shifted side-wise, which is best noticeable as a break in the continuity of retinal vessels.

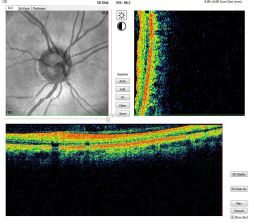

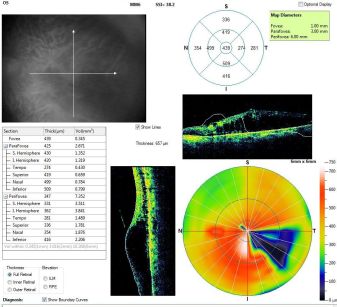

Segmentation error:[14]

The software of the OCT machine automatically detects the border of the inner retina (internal limiting membrane) and the outer retina to calculate the retinal thickness map. The definition of outer retinal margin varies according to the imaging device (inner segment-outer segment junction for Stratus, inner part of RPE for Copernicus and Topcon 3D-OCT 1000, middle of RPE for Cirrus, outer part of RPE for Optovue RTVue 100, and Bruch’s membrane for Spectralis).

The software automatically calculates the distance between the inner and outer margin of the neurosensory retina to give the thickness values in the ETDRS grid of the retinal thickness map. In many cases, including vitreoretinal interface disorders and diseases of the outer retina/choroid (including age-related macular degeneration), this automatic detection may be defective (shifted vertically), resulting in wrong thickness values in the map. Both the outer and inner retinal border lines may shift vertically without causing a change in the macular thickness map values. This is called the segmentation shift.[15]

Retina

OCT is useful in the diagnosis of many retinal conditions, especially when the media is clear. In general, lesions in the macula are easier to image than lesions in the mid and far periphery. OCT can be particularly helpful in diagnosing:

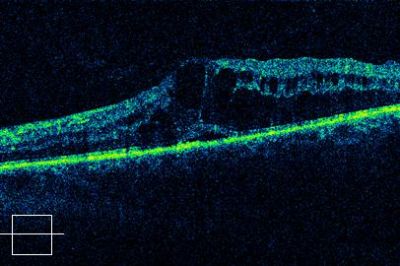

- Macular hole

- Macular pucker/epiretinal membrane

- Vitreomacular traction

- Macular edema and exudates

- Detachments of the neurosensory retina

- Detachments of the retinal pigment epithelium (e.g., central serous chorioretinopathy or age-related macular degeneration)

- Retinoschisis

- Pachychoroid

- Choroidal tumors

In some cases, OCT alone may yield the diagnosis (e.g., macular hole). Yet, in other disorders, especially retinal or choroidal vascular disorders, it may be helpful to order additional tests (e.g. fluorescein angiography or indocyanine green angiography).

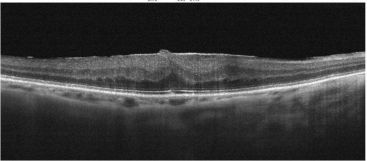

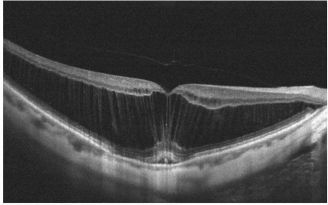

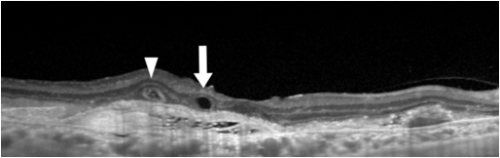

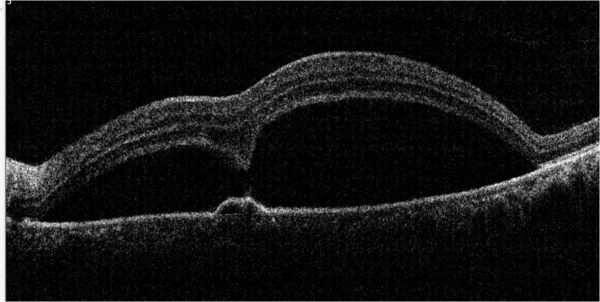

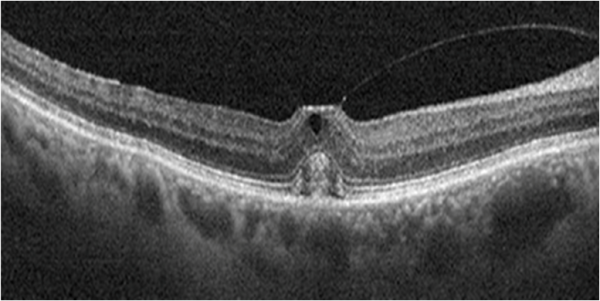

The macular hole on OCT shows partial or full thickness loss of retinal layers overlying the macular area, which may or may not be associated with a vitreomacular traction band.

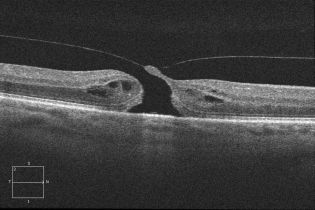

Pseudohole:

The OCT scan of a pseudohole will reveal an epiretinal membrane with no loss of retinal layers. The foveal pit is narrow and vertical. The inner retina is thickened around the fovea. The perifoveal thickness may be increased. The term “pseudohole” reflects the fact that although this looks like a macular hole, it is not a hole in the retina.

Ectopic inner foveal layer (EIFL)

EIFL is characterized by the presence of continuous hyporeflective and hyperreflective bands extending from the inner nuclear layer and inner plexiform layer across the foveal region.[16]

Identifying patterns on Retinal OCT (Hyper and Hypo-reflectivity)

HYPER-REFLECTIVITY

Inner retinal hyper-reflectivity (Diffuse)

In CRAO (central retinal arterial occlusion), inner retinal layers appear as a hyperreflective band that may be swollen.

Focal hyperreflectivity in Hyperreflective Foci (HRF) :

These are typically dot-like or round regular lesions seen in all the retinal layers and choroid, less than 30 microns in size. They typically lack back-shadowing and do not have a representative visible fundus lesion.

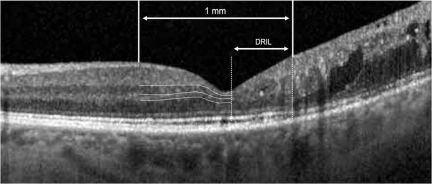

DRIL ( Disorganized retinal inner layers ) :

DRIL is identified when the boundaries of the ganglion cell layer, inner plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, and outer plexiform layer cannot be identified and demarcated. It is a potential biomarker for poor visual prognosis in DME.[17]

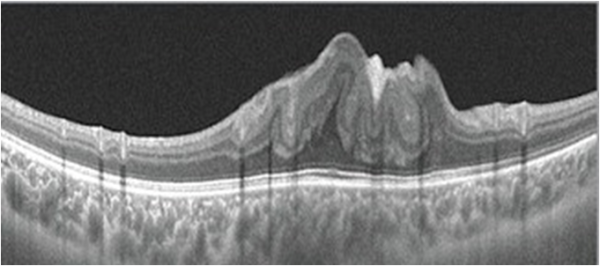

Epiretinal Membrane:

On the slit-lamp fundus examination, the epiretinal membrane (ERM) appears to have an abnormal reflectivity of the macular area, with a loss of normal convex contour and fine wrinkling of the surface. ERM is classified as an early milder form called cellophane macular reflex and a severe late form called preretinal macular fibrosis.[18]

On OCT, an ERM appears as a hyperreflective layer often irregular over the inner surface of the retina. It appears corrugated with peg-like attachments to the retina. Elevation of the foveal depression is seen due to traction from ERM.

HYPO-REFLECTIVITY

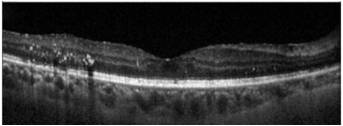

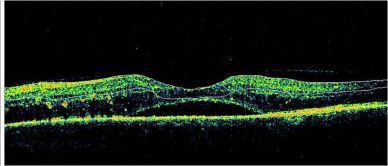

Cystoid macular edema (CME):

Cystoid macular edema can be seen on OCT scans as multiple circular or oval hypo-reflective spaces in the retina, indicating intraretinal edema.

Foveoschisis:[19]

This is characterized by intraretinal splitting at the fovea with vertical tissue bridges connecting the inner and outer retina. Fluorescein angiography does not show petaloid macular leak as is seen in CME. Visual acuity may be disproportionately good despite the increase in the central macular thickness.

Senile Retinoschisis[20]

There is a splitting of retinal layers at the outer plexiform layer, usually in the inferotemporal peripheral fundus in elderly hyperopic patients. On the contrary, retinal detachment shows separation of the neurosensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium.

Important findings on Retinal OCT

Pearl necklace sign:[21]

Hyperreflective dots are arranged in a contiguous ring around the inner wall of cystoid spaces in the outer plexiform layer of the retina. This finding is usually seen in exudative macular diseases.

Paracentral acute middle maculopathy (PAMM):

It is an OCT finding characterized by a parafoveal hyperreflective band at the level of the inner nuclear layer.

Acute macular neuroretinopathy (AMN):

The OCT in AMN shows hyperreflectivity at the outer nuclear layer and the outer side of the outer plexiform layer in the acute stage. Later, there may be outer nuclear thinning.

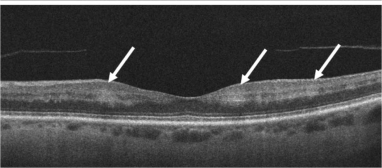

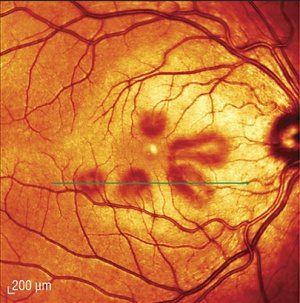

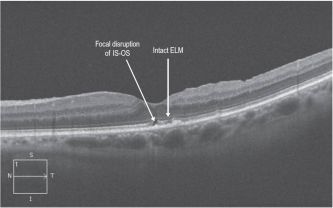

IS-OS (inner segment-outer segment junction, now called the ellipsoid zone or EZ) loss[22]

Disruption of the IS-OS line has been demonstrated to correlate with retinal function loss in several retinal disorders and is considered a useful indicator of photoreceptor integrity and predictor of visual function.

ILM (internal limiting membrane) drape sign in IPFT (idiopathic parafoveal telangiectasia or macular telangiectasia type 2)

The ILM drape sign occurs when a thin membrane overhangs this central hyporeflective lesion at the base of the fovea. The central macular thickness may be reduced. It is seen in macular telangiectasia 2.

Outer Retinal Tubulations ( ORT) :[23]

ORT is a hyporeflective area surrounded by a hyperreflective band in the outer nuclear layer. It comprises interconnecting tubes containing degenerating photoreceptors, almost exclusively cones and Müller cells.

Subretinal hyperreflective material (SHRM) in CNVM:

This SD-OCT feature is identified as hyperreflective material located between the neurosensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

Subretinal hyporeflectivity in SMD (serous macular detachment)[5]

Serous macular detachment (SMD) with cystoid diabetic macular edema (DME) shows retinal elevation with an optically clear space between the sensory retina and the retinal pigment epithelium.

Specific OCT findings in retinal pathologies

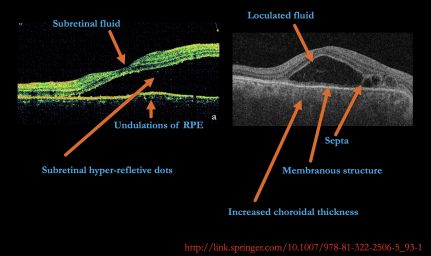

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease (VKH)

In cases of VKH, OCT will demonstrate the presence of subretinal fluid and subretinal hyperreflective dots. In the presence of subtle choroidal folds, they will be detected as corrugation of the RPE/choroid with choroidal thickening. Multiple septae creating compartments or pockets of fluid in the outer retina (bacillary layer detachment) may be seen. Typically, the inner retina inward to the external limiting membrane is normal, though fluctuations in the internal limiting membrane or undulation of the whole neurosensory retina may be noted in some cases. There is increased choroidal thickness in the acute stage.[24]

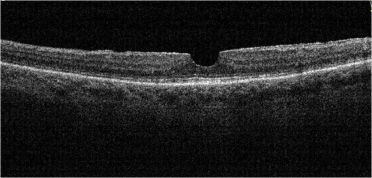

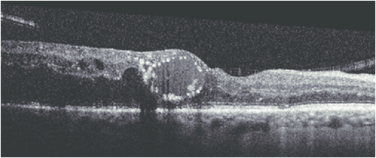

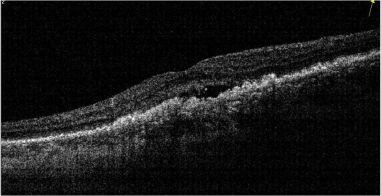

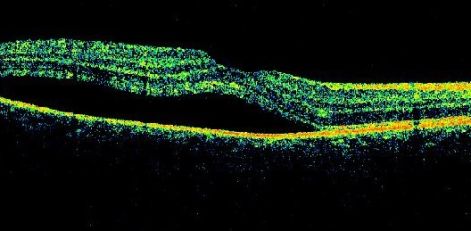

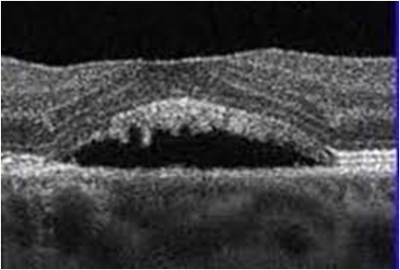

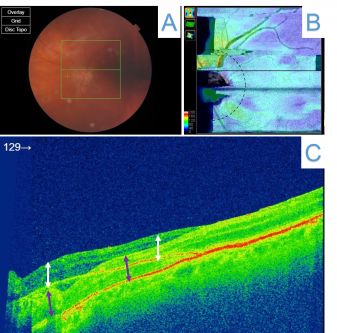

Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (CSCR)

CSCR on OCT shows neurosensory detachment along with clear subretinal fluid often associated with focal serous PED. More recently, enhanced-depth imaging SD-OCT has shown increased subfoveal choroidal thickness in some patients with CSCR, as compared to normal eyes.[25] The outer retinal dipping sign may be noted. Typically, the RPE not involved in serous PED appears straight, unlike inflammatory pathologies, including VKH disease, where the RPE may be undulated.[26]

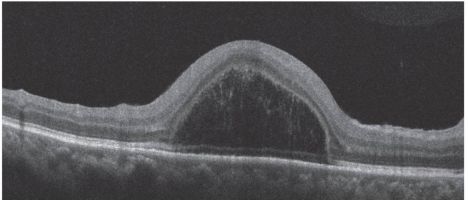

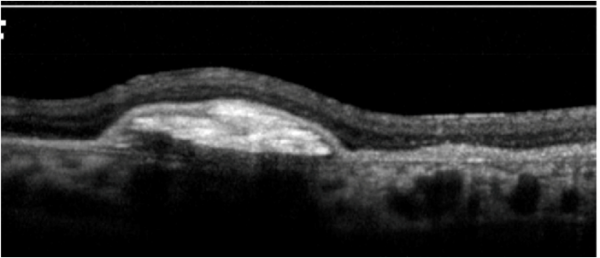

Pigment epithelial detachment (PED)

PED occurs when the RPE gets separated from the underlying Bruch membrane. Depending upon the reflectivity of the sub-RPE material, it can be of various types:[27]

| Type of PED | OCT findings |

|---|---|

| SEROUS | Well-demarcated, abrupt dome-shaped elevations of the RPE with a homogenously hyporeflective sub-RPE space and straight, visible Bruch membrane. Presence of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) should be suspected in the presence of intraretinal or subretinal fluid (SRF), and hyperreflective lesion within the PED. However, SRF may be present on the top or side of a steep serous PED, which may denote a mechanical effect or tenting rather than CNV. |

| FIBROVASCULAR | Irregular RPE elevation with heterogenous structure often along the back surface of the detached RPE. Hemorrhagic PEDs have highly reflective material beneath the PED, casting a shadow effect obscuring the details of external structures, including the Bruch membrane. |

| DRUSENOID |

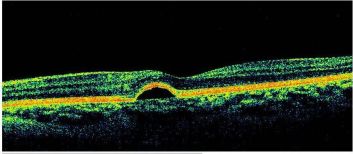

Choroidal Neovascular Membrane (CNVM):

On OCT, CNVM is characterized by subretinal and/or sub-RPE hyperreflective material, sub-RPE hyperreflective columns, RPE tear, or RPE rip. Histopathologically, CNVM (now called macular neovascularization or MNV)[28] has been classified into:

Type 1-CNVM appears beneath the RPE layer and appears as a fibrovascular or hemorrhagic pigment epithelial detachment.

Type 2-CNVM appears above the RPE layer.

Type 3-Neovascularization starts at the retina and progresses posteriorly into subretinal space; eventually, the neovascularization reaches the choroidal circulation and forms retinal-choroidal anastomosis. This is better known as retinal angiomatous proliferation (RAP).

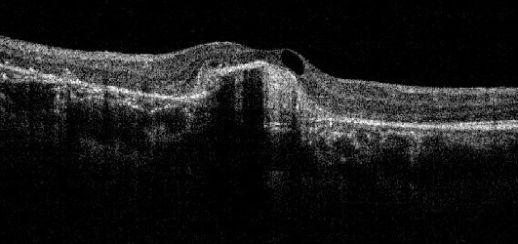

Idiopathic polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (IPCV)

IPCV is a disease of choroidal vasculature characterized by serosanguinous detachments of the pigmented epithelium and exudative changes that commonly lead to subretinal fibrosis. OCT features of IPCV are multiple PEDs, sharp PED peak, PED notch, and rounded sub-RPE hyporeflective area.

Choroidal Nevus:[29]

The enhanced depth imaging (EDI) OCT may show both the anterior and posterior extent of the choroidal nevus. The lesion may be heterogenous with inner hyperreflective area and outer hyporeflective area.[30]

A detailed discussion of OCT features of various posterior segment tumors can be found at https://www.hindawi.com/journals/joph/2011/385058/

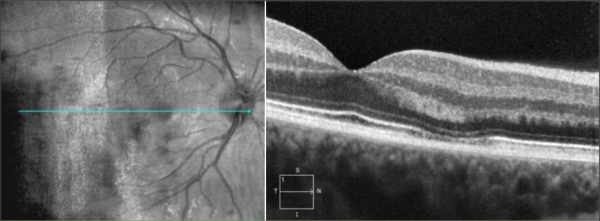

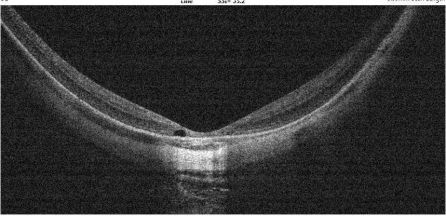

Dome-shaped maculopathy:[31]

It is an anterior convex protrusion of the macula toward the vitreous cavity seen on OCT. It is associated with high myopia and posterior staphyloma.

It exhibits a posterior globe bulge, resulting in a deep concave B-scan OCT and distorted retinal structures.

Bacillary layer detachment (BLD)[32]

BLD is a photoreceptor-splitting detachment. Note the hyperreflective material along the outer retinal surface. A thin band at the base of cystic detachment is continuous with the adjacent ellipsoid band and the external limiting membrane.

Focal choroidal excavation[33]

It is defined as an area of concavity in the choroid detected on OCT. These are mostly present in the macular region without evidence of accompanying scleral ectasia or posterior staphyloma.

Subfoveal perfluorocarbon liquid

The presence of subfoveal perfluorocarbon liquid after vitreoretinal surgery can cause the appearance of a subretinal cyst-like structure.

Other OCT Signs

Dipping sign[34]

Dipping (tenting down) sign may be observed in some acute CSCR (central serous chorioretinopathy) patients. It is characterized by dipping or tenting at the outer surface of the detached neurosensory retina due to hyperreflective material accumulation, such as subretinal fibrin or fibrinous exudate connecting the detached neurosensory retina and RPE detachment.

Omega sign[35]

The omega sign is an omega-shaped disorganization of inner retinal layers bounded posteriorly by the outer plexiform layer. Omega sign is a characteristic feature of macular CHRRPE (combined hamartoma of retina and RPE) and may help to distinguish macular CHRRPEs from ERMs.

Onion sign[36]

The "onion sign" refers to layered hyperreflective bands in the sub-RPE space usually associated with chronic exudation from type 1 neovascularization in patients with AMD (age-related macular degeneration). This dynamic sign is seen in 5-7% of wet AMD cases and is presumed to be composed of cholesterol crystals, Frequency of this sign is higher in individuals taking medications too lower cholesterol.[37]

Cotton-ball sign[38]

The cotton-ball sign is a roundish or diffuse highly reflective region observed between the photoreceptor inner segment/outer segment junction line and the cone outer segment tip line at the center of the fovea. This highly reflective region is a characteristic sign observed in the OCT images of eyes with VMT and ERM.[38]

Brush border pattern[34]

Brush border pattern is an irregular, serrated, and thicker appearance of the detached neurosensory retina seen in CSCR.

It is due to the accumulation of waste products in the photoreceptor outer segment on the outer surface of the detached neurosensory retina over subretinal fluid.

Peripapillary intrachoroidal cavitation (PICC)

This is characterized by intrachoroidal oval hyporeflective space near myopic conus on OCT.

Few other OCT signs:

Vertical hyperreflective line/track

Vertical hyperreflective line (VHRL) or track (VHRT) is defined as a line or track which extends from outer to inner retina on OCT, with or without ellipsoid zone (EZ) disruption. Representative images can be accessed here.

This has been described in acute cases of photic retinopathy (most common cause being solar retinopathy), that resolved on follow-up correlating with the symptomatic improvement.[39]

Ishibashi and colleagues retrospectively noted a novel OCT sign, the “foveal crack sign” (VHRT at umbo with a deformation of the fovea), which preceded full-thickness macular hole (FTMH) formation after vitreoretinal surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.[40]

Scharf and colleagues demonstrated the presence of a central vertically oriented hyperreflective stress line in the fovea on SD-OCT:[41]

- Preceding full-thickness macular hole

- In approximately 50% of the cases after resolution of FTMH following vitrectomy

- In almost one-fourth of the cases of lamellar macular hole.

VHRT at the fovea may also be noted due to RPE plumes (thread or vitelliform variants) in age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). VHRT at the fovea may also be noted in:

- Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS)

- Macular telangiectasia type 2

- Scar

- Diabetic retinopathy

- After resolution of foveal haemorrhage.[42]

VHRT at areas other than fovea may be noted after:

- Macular laser or pan retinal photocoagulation (PRP)

- Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE)

- Self-inflicted laser burns.[41]

SOPLA (split outer plexiform layer appearance)

This is an OCT finding where the outer plexiform layer appears separated into 2 distinct hyperreflective bands with a hyporeflective (darker) space in between.

SOPLA is considered an acquired cone dysfunction phenotype, meaning it develops over time and affects the cone photoreceptors, which are responsible for colour vision and central vision. This is often associated with autoimmune retinopathy.[43]

Müller cell cone

The inner half of the foveola was composed of an inverted cone-shaped zone of Müller cells (Müller cell cone). [44]

The truncated apex of the cone is located at the outer limiting membrane, and the base of the cone formed the floor of the fovea centralis and extended into the area of the clivus in the perifoveolar region.[45]

The Müller cell cone serves as a plug to bind together the receptor cells in the foveola. This also acts as a reservoir of retinal xanthophyll. Without this plug of glial cells, the photoreceptor cell layer would be highly susceptible to disruption at the umbo and subsequent hole formation.

The earliest changes occurring in the development of age-related macular hole involve degeneration of the Müller cell cone–vitreous cortex interface, Müller cell invasion and proliferation within the prefoveolar vitreous cortex, contraction of the prefoveolar vitreous cortex, disruption of the Müller cell cone, full-thickness retinal dehiscence at the umbo, centrifugal retraction of the receptor cell layer, and formation of a pre-hole opacity.[46]

Pre-choroidal cleft

This OCT finding is characterized by the presence of hyporeflective space between the Bruch membrane and hyperreflective materials within pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs). It has been described in patients affected by MNV (macular neovascularization) in 2014.[47]

This space initially named “choroidal cleft” has been further characterized in chronic fibrovascular PED and termed as “prechoroidal cleft.” The origin of the cleft has been attributed to a possible accumulation of the fluid generated by the fibrovascular tissue.

Early development of the cleft has been associated with worse vision in the long term. There is significant increase in size of the prechoroidal cleft in association with MNV reactivation and the reduction of its size following treatment.[48] These cases may be at higher risk of

- Retinal pigment epithelial tear,

- Subretinal hemorrhage,

- Poor visual prognosis, and

- Resistance to anti-VEGF therapy.

Outer retinal columnar abnormalities (ORCA)

This OCT finding is visible as multiform, vertical, hyperreflective, columnar alterations extending from the ellipsoid zone to the outer plexiform layer, with a variable degree of hyporeflective cystic spaces in the outer and inner nuclear layers.

A high suspicion for CRB1-associated retinal dystrophy should arise in the presence of ORCA on SD-OCT, prompting genetic testing.

Dense deposit disease is a rare disease secondary to complement cascade dysregulation, associated with drusen, which can cause bilateral non-vasogenic cystoid macular oedema and outer retinal columnar abnormalities.[49]

Angular sign of Henle fibre layer (HFL) hyperreflectivity (ASHH)

ASHH is an OCT sign that appears as angular hyperreflectivity extending from the outer plexiform layer to the ellipsoid zone.

This sign is a marker of Henle fibre layer ischemia and possibly points toward an insult to the distal part of the deep capillary plexus that might be of inflammatory origin.

This sign has been described in various conditions such as:

- Acute macular neuroretinopathy (AMN)

- Dengue maculopathy

- Contusion maculopathy

- APMPPE

- Retinal vascular diseases. [50]

Reticular Pseudo Drusen (RPD)

These are noted as multiple yellowish-white lesions of the fundus, arranged in a reticular network pattern. On OCT, these lesions show granular hyperreflective deposits situated between the RPE layer and the ellipsoid zone.

Zweifel and colleagues have classified RPD into 3 types according to the OCT findings: [51]

- Type 1 - Hyperreflective material lies between RPE and inner segment-outer segment junction or ellipsoid zone (EZ). There is no elevation or breach of EZ.

- Type 2 - The hyperreflective material accumulates and forms a mound over the RPE with distortion of overlying EZ

- Type 3 - The hyperreflective material has a conical configuration that punctures the EZ and reaches outer retina.

RPD are most commonly seen in association with ARMD, but they may be isolated also. Other associations of RPD include:

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Sorsby macular dystrophy

- Acquired vitelliform lesion.[52]

Dissociated optic nerve fibre layer (DONFL)

DONFL is an appearance of the retina observed after vitrectomy with ILM peeling, though it has been reported in sub-ILM hemorrhage due to various causes including Terson syndrome.[53] It appears as multiple arcuate striae on the inner retinal surface restricted to the area of peeled ILM, and it is more readily visible with shorter wavelength illumination.

This presents on spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) as apparent depressions or dimpling in the nerve fibre layer. En-face OCT images allow better visualization and may indicate the area of the ILM defect.[54]

| OCT finding/entity/sign | Associated diseases | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Retinal Tubulation | AMD, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Bietti's crystalline retinopathy, multifocal choroiditis and experimental uveitis with CNVM, CSCR, choroideremia | Refractory/nonresponsive to AntiVEGF therapy

A finding of longterm-lasting CNVM Poor visual outcome |

| Flying saucer | Antimalarial drug induced maculopathy | Perifoveal loss of the photoreceptor IS/OS junction

A possible sign of preclinical stage of antimalarial drug toxicity |

| Focal Choroidal Excavation | AMD, CSCR, ERM, PCV, VKH, multifocal choroiditis and punctate inner choroidopathy, focal retinochoroiditis | Usually stationary

Rarely choroidal neovascularization |

| Dipping Sign | CSCR | Acute cases

Fibrinous exudate Dipping or tenting at the outer surface of detached neurosensory retina |

| Pearl Necklace Sign | AMD, DME, retinal vein occlusion, retinal arterial macroaneurysm, Coats disease | A sign of chronic exudative maculopathy

A sign of a particularly excessive macular edema |

| Foveal Pseudo-Cyst | Previous vitreoretinal surgery with perfluorocarbon liquid

Subretinal subfoveal liquid retantion |

A serious complication

Toxic to the RPE and photoreceptors Necessary for surgical removal of subfoveal retained liquid |

| Dome-shaped Macula | High myopia, Posterior staphyloma | Anteriorly configuration of the macula

Macular convexity Difficult identification in ophthalmoscopy |

| Brush-Border pattern | CSCR | Accumulation of waste products in photoreceptor outer segments

Elongation of photoreceptor outer segments Chronic cases |

| Peripapillary Intrachoroidal cavitation | Myopia | |

Various Classifications based on OCT

Macular Hole classification:

The International Vitreomacular Traction Study (IVTS) classification scheme of vitreomacular traction and macular holes based on OCT findings:[55]

| Vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) | No distortion of the foveal contour; size of attachment area between hyaloid and retina defined as focal if ≤ 1500 microns and broad if >1500 microns |

| Vitreomacular traction (VMT) | Distortion of foveal contour present or intraretinal structural changes in the absence of a full-thickness macular hole; size of attachment area between hyaloid and retina defined as focal if ≤ 1500 microns and broad if >1500 microns |

| Full-thickness macular hole (FTMH) | Full-thickness defect from the internal limiting membrane to the retinal pigment epithelium is described based on 3 factors:

1) Size -horizontal diameter at narrowest point: small (≤ 250 μm), medium (250-400 μm), large (> 400 μm) 2) Cause -primary or secondary 3) Presence or absence of VMT |

Diabetic macular edema (DME) classification:

Morphologically, DME may be classified into:[56]

| OCT CLASSIFICATION OF DME | |

| 1 | Diffuse retinal thickening |

| 2 | Cystoid macular edema |

| 3 | Posterior hyaloid traction |

| 4 | Subretinal fluid/serous retinal detachment |

| 5 | Tractional retinal detachment |

Epiretinal membrane (ERM) classification:

Based on OCT Morphology, Idiopathic ERM has been classified into:[57]

| Group 1: Fovea-involving ERM

1 A: Outer retinal thickening and minimal inner retinal change 1 B : Outer retinal inward projection and inner retinal thickening 1 C: Prominent thickening of the inner retinal layer |

| Group 2: Fovea-sparing ERM

2 A: Formation of a macular pseudohole 2 B: Schisis-like intraretinal splitting |

Ectopic inner foveal layer Classification:[58]

| Ectopic Inner Foveal Layer classification | |

| Stage 1 ERM | Epiretinal membrane with foveal preservation |

| Stage 2 ERM | ERM

Loss of foveal depression Thickening of ONL |

| Stage 3 ERM | ERM

Loss of foveal depression Continuous & clearly identified EIFL |

| Stage 4 ERM | ERM with loss of foveal depression

EIFL with anatomy & identification completely lost |

Optic nerve

OCT is gaining popularity when evaluating optic nerve disorders by accurately and reproducibly evaluating the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer thickness:

- Glaucoma

- Optic neuritis

- Non-glaucomatous optic neuropathies

- Alzheimer disease

Anterior segment

Anterior segment OCT utilizes higher wavelength light than traditional posterior segment OCT. This higher wavelength light results in greater absorption and less penetration. In this fashion, images of the anterior segment (cornea, anterior chamber, iris, and angle) can be visualized. Anterior segment OCT can show lesions of the cornea, anterior chamber, iris, angle of the anterior chamber, conjunctiva, and anterior sclera.

Limitations

Because OCT utilizes light waves (unlike ultrasound which uses sound waves), media opacities can interfere with optimal imaging. As a result, the OCT will be limited in the setting of vitreous hemorrhage, dense cataracts, or corneal opacities.

As with most diagnostic tests, patient cooperation is a necessity. Patient movement can diminish the quality of the image. With newer machines, acquisition time is shorter, which may result in fewer motion-related artifacts.

The quality of the image is also dependent on the operator of the machine. Early models of OCT relied on the operator to accurately place the image over the desired pathology. When serial images were acquired over time (eg, during treatment for AMD with anti-VEGF therapy), later images could be taken that were off-axis compared to earlier images. Newer technologies, such as eye-tracking equipment, limit the likelihood of acquisition error.

Additional Resources

- Turbert D, Janigian RH. Optical Coherence Tomography. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye Health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/treatments/optical-coherence-tomography-list. Accessed July 21, 2025.

References

- ↑ Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254(5035):1178-1181.

- ↑ Wojtkowski M, Bajraszewski T, Gorczyńska I, et al. Ophthalmic imaging by spectral optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004 Sep;138(3):412-9.

- ↑ Spaide RF, Koizumi H, Pozzoni MC. Enhanced depth imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 Oct;146(4):496-500. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.032. Epub 2008 Jul 17. Erratum in: Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Aug;148(2):325. Pozonni, Maria C [corrected to Pozzoni, Maria C]. PMID: 18639219.

- ↑ Adhi M, Liu JJ, Qavi AH, et al. Choroidal Analysis in Healthy Eyes using Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Compared to Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(6):1272-81.e1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bhende M, Shetty S, Parthasarathy MK, Ramya S. Optical coherence tomography: A guide to interpretation of common macular diseases. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018 Jan;66(1):20-35. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_902_17. Erratum in: Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018 Mar;66(3):485. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.226132. PMID: 29283118; PMCID: PMC5778576.

- ↑ Staurenghi G, Sadda S, Chakravarthy U, Spaide RF; International Nomenclature for Optical Coherence Tomography (IN•OCT) Panel. Proposed lexicon for anatomic landmarks in normal posterior segment spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: the IN•OCT consensus. Ophthalmology. 2014 Aug;121(8):1572-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.023. Epub 2014 Apr 19. PMID: 24755005.

- ↑ Spaide RF, Curcio CA. Anatomical correlates to the bands seen in the outer retina by optical coherence tomography: literature review and model. Retina. 2011 Sep;31(8):1609-19. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182247535. PMID: 21844839; PMCID: PMC3619110.

- ↑ Spaide RF. Questioning optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2012 Nov;119(11):2203-2204.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.009. PMID: 23122463.

- ↑ Ho J, Castro DP, Castro LC, Chen Y, Liu J, Mattox C, Krishnan C, Fujimoto JG, Schuman JS, Duker JS. Clinical assessment of mirror artifacts in spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 Jul;51(7):3714-20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4057. Epub 2010 Feb 24. PMID: 20181840; PMCID: PMC2904018.

- ↑ Anvari P, Ashrafkhorasani M, Habibi A, Falavarjani KG. Artifacts in Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2021 Apr 29;16(2):271-286. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v16i2.9091. PMID: 34055264; PMCID: PMC8126744.

- ↑ Bazvand F, Ghassemi F. Artifacts in Macular Optical Coherence Tomography. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2020 Apr 30;32(2):123-131. doi: 10.4103/JOCO.JOCO_83_20. PMID: 32671295; PMCID: PMC7337029.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chhablani J, Krishnan T, Sethi V, Kozak I. Artifacts in optical coherence tomography. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014 Apr;28(2):81-7. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2014.02.010. PMID: 24843299; PMCID: PMC4023112.

- ↑ Anvari P, Ashrafkhorasani M, Habibi A, Falavarjani KG. Artifacts in Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2021 Apr 29;16(2):271-286. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v16i2.9091. PMID: 34055264; PMCID: PMC8126744.

- ↑ Patel PJ, Chen FK, da Cruz L, Tufail A. Segmentation error in Stratus optical coherence tomography for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009 Jan;50(1):399-404. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1697. Epub 2008 Aug 1. PMID: 18676631.

- ↑ Spaide RF, Fujimoto JG, Waheed NK. Image artifacts in optical coherence tomography angiography. Retina 2015;35:2163‑80.

- ↑ Doguizi, S., Sekeroglu, M.A., Ozkoyuncu, D. et al. Clinical significance of ectopic inner foveal layers in patients with idiopathic epiretinal membranes. Eye 32, 1652–1660 (2018)

- ↑ Markan, A., Agarwal, A., Arora, A., Bazgain, K., Rana, V., & Gupta, V. (2020). Novel imaging biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Therapeutic advances in ophthalmology, 12, 2515841420950513. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515841420950513

- ↑ Kanukollu VM, Agarwal P. Epiretinal Membrane. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560703/

- ↑ Gohil R, Sivaprasad S, Han LT, Mathew R, Kiousis G, Yang Y. Myopic foveoschisis: a clinical review. Eye (Lond). 2015 May;29(5):593-601. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.311. Epub 2015 Mar 6. PMID: 25744445; PMCID: PMC4429265.

- ↑ Mandura RA. Acquired Senile Retinoschisis of the Peripheral Retina Imaged by Spectral Domain Optical Coherent Tomography. Cureus. 2021 Apr 18;13(4):e14540. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14540. PMID: 34017655; PMCID: PMC8130636.

- ↑ Gelman SK, Freund KB, Shah VP, Sarraf D. The pearl necklace sign: a novel spectral domain optical coherence tomography finding in exudative macular disease. Retina. 2014 Oct;34(10):2088-95. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000207. PMID: 25020214.

- ↑ Tao LW, Wu Z, Guymer RH, Luu CD. Ellipsoid zone on optical coherence tomography: a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 Jul;44(5):422-30. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12685. Epub 2016 Feb 11. PMID: 26590363.

- ↑ Arrigo A, Aragona E, Battaglia O, Saladino A, Amato A, Borghesan F, Pina A, Calcagno F, Hassan Farah R, Bandello F, Battaglia Parodi M. Outer retinal tubulation formation and clinical course of advanced age-related macular degeneration. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 19;11(1):14735. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94310-5. PMID: 34282240; PMCID: PMC8289974.

- ↑ Tripathy K, Agarwal A, Singh RB, Aggarwal K, Gupta V. (2018). Vogt Koyanagi Harada Disease. In: Gupta, V., Nguyen, Q., LeHoang, P., Herbort Jr., C. (eds). The Uveitis Atlas. Springer, New Delhi. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2506-5_93-1

- ↑ Imamura Y, Fujiwara T, Margolis R, Spaide RF. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of the choroid in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2009 Nov-Dec;29(10):1469-73. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181be0a83. PMID: 19898183.

- ↑ Gupta A, Tripathy K. Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. 2023 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. PMID: 32644399.

- ↑ Karampelas M, Malamos P, Petrou P, Georgalas I, Papaconstantinou D, Brouzas D. Retinal Pigment Epithelial Detachment in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020 Dec;9(4):739-756. doi: 10.1007/s40123-020-00291-5. Epub 2020 Aug 18. PMID: 32809132; PMCID: PMC7708599.

- ↑ Spaide RF, Jaffe GJ, Sarraf D, Freund KB, Sadda SR, Staurenghi G, Waheed NK, Chakravarthy U, Rosenfeld PJ, Holz FG, Souied EH, Cohen SY, Querques G, Ohno-Matsui K, Boyer D, Gaudric A, Blodi B, Baumal CR, Li X, Coscas GJ, Brucker A, Singerman L, Luthert P, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Grossniklaus HE, Wilson DJ, Guymer R, Yannuzzi LA, Chew EY, Csaky K, Monés JM, Pauleikhoff D, Tadayoni R, Fujimoto J. Consensus Nomenclature for Reporting Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Data: Consensus on Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Nomenclature Study Group. Ophthalmology. 2020 May;127(5):616-636. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.11.004. Epub 2019 Nov 14. Erratum in: Ophthalmology. 2020 Oct;127(10):1434-1435. PMID: 31864668.

- ↑ Chien JL, Sioufi K, Surakiatchanukul T, Shields JA, Shields CL. Choroidal nevus: a review of prevalence, features, genetics, risks, and outcomes. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017 May;28(3):228-237. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000361. PMID: 28141766.

- ↑ Say EA, Shah SU, Ferenczy S, Shields CL. Optical coherence tomography of retinal and choroidal tumors. J Ophthalmol. 2012;2012:385058. doi: 10.1155/2012/385058. Epub 2011 Jun 8. PMID: 23008756; PMCID: PMC3139893.

- ↑ Jain M, Gopal L, Padhi TR. Dome-shaped maculopathy: a review. Eye (Lond). 2021 Sep;35(9):2458-2467. doi: 10.1038/s41433-021-01518-w. Epub 2021 Apr 19. PMID: 33875828; PMCID: PMC8377053.

- ↑ Ramtohul P, Engelbert M, Malclès A, Gigon E, Miserocchi E, Modorati G, Cunha de Souza E, Besirli CG, Curcio CA, Freund KB. BACILLARY LAYER DETACHMENT: MULTIMODAL IMAGING AND HISTOLOGIC EVIDENCE OF A NOVEL OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY TERMINOLOGY: Literature Review and Proposed Theory. Retina. 2021 Nov 1;41(11):2193-2207. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003217. PMID: 34029276.

- ↑ Cebeci Z, Bayraktar Ş, Oray M, Kır N. Focal Choroidal Excavation. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2016 Dec;46(6):296-298. doi: 10.4274/tjo.24445. Epub 2016 Dec 1. PMID: 28050329; PMCID: PMC5177789.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Turgut B, Demir T. (2016). The new landmarks, findings, and signs in optical coherence tomography. New Frontiers in Ophthalmology. 2.10.15761/NFO.1000130.

- ↑ Kumar V, Chawla R, Tripathy K. Omega Sign: A Distinct Optical Coherence Tomography Finding in Macular Combined Hamartoma of Retina and Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2017 Feb 1;48(2):122-125. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20170130-05. PMID: 28195614.

- ↑ Venkatesh R, Mangla R, Sharief S, Arora S, Reddy NG, Yadav NK, Chhablani J. Onion ring sign on spectral domain optical coherence tomography in diabetic macular edema: Its evolution and outcomes. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023 Sep;33(5):2006-2013. doi: 10.1177/11206721231154187. Epub 2023 Jan 26. PMID: 36703256.

- ↑ Pang CE, Messinger JD, Zanzottera EC, Freund KB, Curcio CA. The Onion Sign in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Represents Cholesterol Crystals. Ophthalmology. 2015 Nov;122(11):2316-26. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.07.008. Epub 2015 Aug 19. PMID: 26298717; PMCID: PMC4706534.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Tsunoda K, Watanabe K, Akiyama K, Usui T, Noda T. Highly reflective foveal region in optical coherence tomography in eyes with vitreomacular traction or epiretinal membrane. Ophthalmology. 2012 Mar;119(3):581-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.026. Epub 2011 Nov 23. PMID: 22115711.

- ↑ Padhy, Srikanta K; Tripathy, Koushik1,. Commentary: Clinical significance of vertical hyper-reflective track in optical coherence tomography of the fovea. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology - Case Reports 2(2):p 473-474, Apr–Jun 2022. | DOI: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_62_22

- ↑ Ishibashi T, Iwama Y, Nakashima H, Ikeda T, Emi K. Foveal Crack Sign: An OCT Sign Preceding Macular Hole After Vitrectomy for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020 Oct;218:192-198. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.05.030. Epub 2020 May 29. PMID: 32479809

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Scharf JM, Hilely A, Preti RC, Grondin C, Chehaibou I, Greaves G, Tran K, Wang D, Ip MS, Hubschman JP, Gaudric A, Sarraf D. Hyperreflective Stress Lines and Macular Holes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020 Apr 9;61(4):50. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.4.50. PMID: 32347919; PMCID: PMC7401923

- ↑ Rein AP, Totah H, Brosh K, Zadok D, Hanhart J. Foveal hyper-reflective vertical lines detected by optical coherence tomography: Imaging features, literature review and differential diagnoses. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2025 Mar;263(3):849-855. doi: 10.1007/s00417-024-06616-5. Epub 2024 Oct 15. PMID: 39404899; PMCID: PMC11953122.

- ↑ Boyce TM, Fortenbach C, Thurtell M, Stone EM, Han IC. SPLIT OUTER PLEXIFORM LAYER APPEARANCE REPRESENTS AN ACQUIRED CONE DYSFUNCTION PHENOTYPE OF AUTOIMMUNE RETINOPATHY. Retina. 2025 Mar 1;45(3):522-531. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000004332. PMID: 39964825.

- ↑ Ho, TC., Ho, A.YL. & Chen, MS. Reconstructing Foveola by Foveolar Internal Limiting Membrane Non-Peeling and Tissue Repositioning for Lamellar Hole-Related Epiretinal Proliferation. Sci Rep 9, 16030 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52447-4

- ↑ Yamada E Some structural features of the fovea centralis in the human retina. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;82151- 159

- ↑ Gass JD. Müller cell cone, an overlooked part of the anatomy of the fovea centralis: hypotheses concerning its role in the pathogenesis of macular hole and foveomacualr retinoschisis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999 Jun;117(6):821-3. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.6.821. PMID: 10369597.

- ↑ Spaide RF. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of retinal pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.10.005.

- ↑ Cozzi M, Monteduro D, Parrulli S, Ristoldo F, Corvi F, Zicarelli F, Staurenghi G, Invernizzi A. Prechoroidal cleft thickness correlates with disease activity in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022 Mar;260(3):781-789. doi: 10.1007/s00417-021-05384-w. Epub 2021 Sep 7. PMID: 34491426; PMCID: PMC8850287

- ↑ Grimaldi G, Menghini M, Mahroo OA, Webster AR, Michaelides M, Peng CL, Egan C, Tufail A. OUTER RETINAL COLUMNAR ABNORMALITIES: A Novel Optical Coherence Tomography Sign of CRB1 Maculopathy? Retina. 2024 Nov 1;44(11):2013-2018. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000004223. PMID: 39089008

- ↑ Ramtohul P, Cabral D, Sadda S, Freund KB, Sarraf D. The OCT angular sign of Henle fiber layer (HFL) hyperreflectivity (ASHH) and the pathoanatomy of the HFL in macular disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023 Jul;95:101135. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2022.101135. Epub 2022 Nov 1. PMID: 36333227

- ↑ Zweifel SA, Spaide RF, Curcio CA, Malek G, Imamura Y. Reticular pseudodrusen are subretinal drusenoid deposits. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(2):303–12.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.014

- ↑ Domalpally A, Agrón E, Pak JW, et al. Prevalence, Risk, and Genetic Association of Reticular Pseudodrusen in Age-related Macular Degeneration: Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Report 21. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(12):1659–1666. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.07.022

- ↑ Tripathy K. Dissociated optic nerve fiber layer in a case of Terson syndrome. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;30(5):NP11-NP14. doi:10.1177/1120672119853465

- ↑ Runkle AP, Srivastava SK, Yuan A, Kaiser PK, Singh RP, Reese JL, Ehlers JP. FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH DEVELOPMENT OF DISSOCIATED OPTIC NERVE FIBER LAYER APPEARANCE IN THE PIONEER INTRAOPERATIVE OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY STUDY. Retina. 2018 Sep;38 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S103-S109. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002017. PMID: 29346239; PMCID: PMC6047929.

- ↑ Duker JS, Kaiser PK, Binder S, de Smet MD, Gaudric A, Reichel E, Sadda SR, Sebag J, Spaide RF, Stalmans P. The International Vitreomacular Traction Study Group classification of vitreomacular adhesion, traction, and macular hole. Ophthalmology. 2013 Dec;120(12):2611-2619. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.07.042. Epub 2013 Sep 17. PMID: 24053995.

- ↑ Kim BY, Smith SD, Kaiser PK. Optical coherence tomographic patterns of diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Sep;142(3):405-12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.023. PMID: 16935584.

- ↑ Hwang JU, Sohn J, Moon BG, Joe SG, Lee JY, Kim JG, Yoon YH. Assessment of macular function for idiopathic epiretinal membranes classified by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012 Jun 14;53(7):3562-9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9762. PMID: 22538422.

- ↑ Govetto A, Lalane RA, 3rd, Sarraf D, Figueroa MS, Hubschman JP. Insights into epiretinal membranes: presence of ectopic inner foveal layers and a new optical coherence tomography staging scheme. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;175:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.12.006.