Lacrimal Sac Tumors

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Lacrimal sac tumors are rare but often malignant neoplasms, frequently misdiagnosed as chronic dacryocystitis or nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Early recognition is critical, as delayed diagnosis can lead to invasion, recurrence, and metastasis. Management requires accurate histopathology and a multidisciplinary approach with surgery and adjuvant therapy.

Disease

Lacrimal sac tumors are rare, but their early recognition and management is imperative as the tumors can be locally invasive and potentially life threatening. While these tumors can be benign or malignant, approximately 55% of lacrimal sac tumors are malignant. Mortality rates for malignant tumors are variable and dependent on the type and stage of the malignancy. Notably, fatal outcomes are reported in up to a third of patients. Patients can present with a wide variety of signs and symptoms, including with symptoms of secondary acquired nasolacrimal obstruction. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

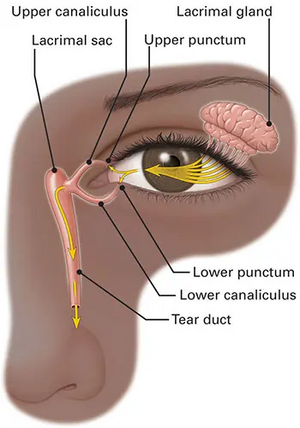

Anatomy of the lacrimal-canalicular system

Secretory component

- Composed of the Main Lacrimal Gland and the Accessory Lacrimal Glands (Wolfring and Krause).

- Purpose: produce the middle aqueous component of the tear which then reaches the globe and receives the oily layer and the mucin layer from the conjunctiva and sebaceous glands of the eyelid.

Excretory component

- Composed of the puncta (orifice) that leads to the ampulla, and enters the superior and inferior canaliculus, which then combine to form the common canaliculus.

- The common canaliculus enters the lacrimal sac (located within the lacrimal fossa) by passing through the Valve of Rosenmüller.

- The nasolacrimal duct extends inferiorly from lacrimal sac into the nasolacrimal canal. The Valve of Hasner is located at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct, opening into the inferior meatus of the nasal cavity, just beneath the inferior turbinate.[6]

Physiology of the Lacrimal Drainage Apparatus

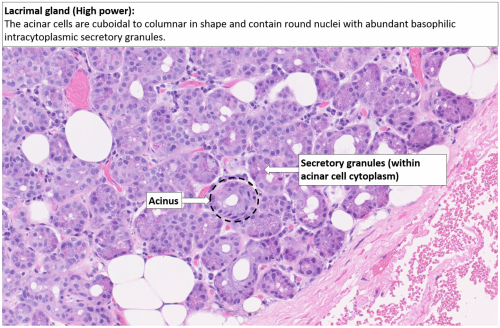

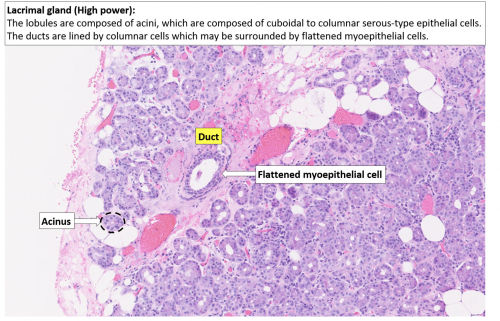

The lacrimal gland produces tears which are composed of three layers: inner mucus layer (produced by conjunctival epithelium and goblet cells), aqueous middle layer (produced by the main lacrimal gland, Wolfring, and Krause glands), and outer oil layer (meibomian and Zeiss glands). The lacrimal gland sits in the anterior, superolateral orbit within the lacrimal fossa (located within the frontal bone) and is a type of exocrine (exits to the surface), eccrine sweat gland. The lacrimal gland is divided by the lateral portion of the levator aponeurosis into two lobes: the orbital and the palpebral lobe. There are also accessory lacrimal glands in the eyelid known as the Wolfring and Krause glands.

The lacrimal gland is composed of cuboidal epithelium in a round formation with the nucleation on the outer edge of the acinus. These acini exit into the lacrimal ducts which are composed of two cell layers: an inner cuboidal epithelium, with an outer lining of flat, myoepithelial cells. The cuboidal cells in the acini produce secretory proteins inside zymogen granules. The zymogen granules are composed of lysozyme, lactoferrin, peroxidase, immunoglobulin and lipocalin.

After the middle aqueous layer of tears are deposited on the globe from the main lacrimal gland and the accessory lacrimal glands, the mucin and oily layers are added to form the complete tear film. The tear lubricates the globe, and with each eyelid closure, the tears are collected into the puncta, The superior and inferior puncta and then drain into the inferior and superior canaliculi. From the common canaliculus the tears pass through the valve of Rosenmüller into the lacrimal sac, where they then flow down the nasolacrimal duct, the Valve of Hasner, and finally into the nasal cavity via the inferior meatus.

Neurovascular supply of the Secretory Component:

- Arterial supply: Lacrimal branch of the ophthalmic artery (Lacrimal artery) and the infraorbital branch of the internal maxillary artery.

- Venous supply: Lacrimal vein

- Main lacrimal gland is innervated by Afferent pathway (CN V1), and the efferent pathway (Facial n.)

- The lacrimal nerve carries the sensory fibers FROM the lacrimal gland to the V1 branch of the Trigeminal nerve.

- The facial nerve carries the parasympathetic fibers to the lacrimal gland which can cause reflex tears in the lacrimal gland.

Epidemiology

Benign tumors tend to present in younger patients, while malignant tumors present more commonly in the fifth decade.[4] Chronic inflammation, viral oncogenesis, and radiation exposure are other contributing factors.[7]

Signs and Symptoms

Most patients with lacrimal sac tumors present with signs and symptoms of chronic nasolacrimal duct obstruction, typically presenting as unilateral epiphora with or without a palpable mass in the lacrimal sac area. Hemolacria (blood-stained tears), have also been reported.

The diagnosis of lacrimal sac tumor is typically made incidentally; unusual tissue is noticed during a dacryocystorhinostomy and so a biopsy is done. Late-stage tumors may present with signs of orbital invasion, such as proptosis and nonaxial globe displacement (hypoglobus, hyperglobus, or deviation away from the mass), lymphadenopathy, overlying skin ulceration, and rarely, distant metastasis. . [4][8] [9]

Pathology

Lacrimal sac tumors can be divided into epithelial and non-epithelial tumors, and further sub-categorized as benign or malignant.

Epithelial tumors

Epithelial tumors account for 60-94% of tumors. The lacrimal sac, like the upper respiratory tract, is lined by a pseudostratified columnar epithelium with cilia and goblet cells.

Benign Epithelial Tumors

Benign epithelial tumors include papillomas, oncocytomas, adenomas and cylindromas.

- Papillomas are the most common and comprise 36% of epithelial tumors. They are believed to develop secondary to pre-existing inflammation through squamous metaplasia. It is important to note that though papillomas are designated as "benign," the inverted papilloma type is associated with aggressive growth and recurrence, requiring careful management.

- Papillomas present as an exophytic or endophytic growth on histopathology. They develop as a painless slow-growing mass in the medial canthal region and have a 5-year recurrence-free survival rate of 67%.

- Management is endoscopic surgical excision or laser thermos-ablation, and there is no risk of malignant transformation.[10][11]

- Adenomas typically arise from the lacrimal duct but there have been cases reported of ectopic lacrimal gland tissue in other parts of the orbit, including the lacrimal sac, which have a potential for malignant transformation.

- Oncocytomas (oxyphil cell adenomas) are composed of polyhedric cells with abundant oxyphil cytoplasm, which is granular and contains large numbers of abnormal mitochondria. The tumor cells stain strongly for antimitochondrial antibody MU213-UC, cytokeratin (CK) 5/6, CK 7, CK 17, CK 8/18 and CK 19.

Malignant Epithelial Tumors

Malignant epithelial tumors or carcinomas generally arise de novo but can also arise from an existing papilloma.

- Squamous cell carcinomas present histopathologically as a well-differentiated tumor with keratin pearls and are most common.[7][16] Inverted papillomas are locally aggressive tumors with a propensity for recurrence and malignant transformation, typically transforming to squamous cell carcinoma. A risk factor for both inverted papilloma and squamous cell carcinoma is human papillomavirus, specifically strains HPV-6 and HPV-18. Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended for most cases of squamous cell carcinoma, especially with positive margins or advanced disease. Chemotherapy or immunotherapy may be considered for recurrent or metastatic disease.

- Transitional cell carcinomas present as aggressive tumors with a papillary growth pattern arising from the transitional epithelium that lines the lacrimal drainage system. Management is complete surgical excision with wide local resection. Long-term follow-up is needed as these have high recurrence rates. [17][18][19]

- Oncocytic adenocarcinomas are aggressive tumors with nuclear atypia arranged in a pseudoglandular pattern on histopathology. Management is surgical excision with wide local resection. Adjuvant radiation therapy is often indicated as well. These have high recurrence rates and need close follow-up. [20][21][22]

- Mucoepidermoid carcinomas are rare tumors composed of a mixture of mucus-secreting cells, epidermoid cells, and basal cells. Management is surgical excision with clear margins. There is a risk of late recurrence, so long-term follow-up is important. [23]

- Cystic adenoid carcinomas are tumors composed of cells arranged in a cribriform pattern of epithelial and myoepithelial cells. Management is complete surgical excision with adjuvant radiation therapy. Recurrence rates are very high, and are between 70-100% in different studies. [24] [25]

Non-Epithelial Tumors

As compared to epithelial tumors, non-epithelial tumors are rarer, representing about 25% of lacrimal sac tumors. Non-epithelial tumors can be further divided into lymphoproliferative, melanocytic, and mesenchymal tumors.

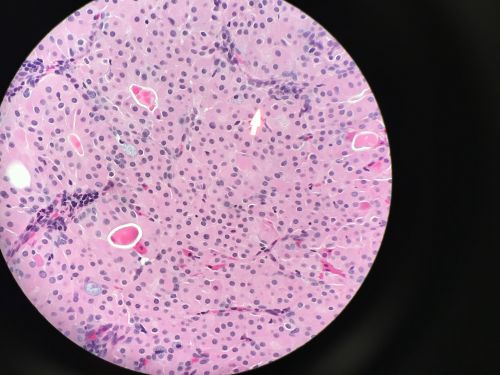

- Lymphoproliferative tumors account for approximately 2-8% of lacrimal sac tumors. These tumors may be primary tumors of the lacrimal sac, but more commonly arise secondary to systemic spread in a patient with leukemia or lymphoma.[26] The majority of are low-grade non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas, and may be primary or secondary to systemic disease.

- MALT lymphomas are the most common and are identified by small mature B cells in the mucosal layers. Management is local radiation therapy or systemic therapy for disseminated disease. Prognosis is excellent with treatment.[27][28]

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas are very aggressive and present histopathologically as large pleomorphic cells with high mitotic rates. Management is systemic chemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone). They have higher recurrence rates. [29][30][31]

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (SLL) are typically secondary to systemic disease, and orbital involvement usually represents later disease. They both contain small, mature lymphocytes with clumped chromatin and proliferation, but they can be differentiated by their cell count. CLL has a persistent peripheral blood monoclonal B-cell count greater than 5 × 10⁹/L, while SLL has less than 5 × 10⁹/L. They are treated similarly by systemic therapy with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies or BTK inhibitors. Local radiotherapy may be added for symptomatic benefit. [31]

- Melanocytic tumors account for 4-5% of lacrimal sac tumors. Benign lesions are incredibly rare with only a single case of a benign lacrimal sac nevus, and a handful of cases of lacrimal sac benign melanosis reported in the literature. Malignant melanomas account for 0.7% of ocular melanomas. The tumors arise either from melanocytes in the epidermal lining of the lacrimal sac or secondary to seeding of conjunctival melanomas along the lacrimal drainage system.[4][32] [33] They are histologically similar to skin melanomas and have similar staining on immunohistochemistry (S100, HMB-45, Melan-A). They are treated by surgical excision and radiation therapy. [34][35]

- Mesenchymal tumors constitute 12-14% of lacrimal sac tumors. Benign mesenchymal tumors include fibrous histiocytoma, which is the most common, followed by fibroma, hemangioma, hemangiopericytoma, angiofibroma, lipoma, leiomyoma, and osteoma. Malignant mesenchymal tumors of the lacrimal sac include Kaposi sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. [4][36] [37]

- Benign lesions are incredibly rare with only a single case of a benign lacrimal sac nevus, and a handful of cases of lacrimal sac benign melanosis reported in the literature.

Benign Mesenchymal Tumors

- Fibrous histiocytomas are the most common type and are characterized by spindle-shaped cells arranged in a storiform pattern, often with foamy histiocytes and areas of hypo- and hyper-cellularity. These often present in younger patients as a slowly enlarging rubbery or firm mass with no bony or other local involvement. Management is with surgical excision and monitoring for possible recurrence, although malignant transformation is very rare. These often present in younger patients. [38][39]

- Fibromas are characterized by spindle-shaped cells in a collagenous or myxoid stroma on histopathology. Immunohistochemistry is positive for vimentin and negative for S-100. Management is complete surgical excision and there is low risk of recurrence if margins are clear. They do not have any storiform or histiocytic patterns, which differentiates them from fibrous histiocytomas.[40]

- Hemangiomas are are identified on histopathology by endothelial cells and are positive for CD31, CD34, Factor VIII-related antigen and negative for D2-40 (present in lymphangioma). These are rarer and can be cavernous or vascular. Due to their vascularity, hemangiomas are more likely to bleed if irritated. Management is complete resection with an excellent prognosis and a very low risk of recurrence. [41]

- Hemangiopericytomas demonstrate a histologic pattern of tightly packed spindle cells around branching, thin-walled "staghorn" vessels. Immunohistochemistry is often positive for CD34 and vimentin and negative for S-100. Management is complete surgical excision and long-term follow up due to risk of late recurrence (up to 15 years later). There has been only a handful of cases reported.[42][43]

- Angiofibromas are rare vascular/fibrous tumors that are identified by a proliferation of stellate and spindled cells around blood vessels with or without concentric collagen bundles.

- Lipomas are a benign tumor of adipocytes that can be diagnosed by imaging or histopathology. They are very rare in the lacrimal sac and may mimic a dacryocystocele. More often, they present in the orbit or the eyelids. Management is surgical excision, externally or endoscopically. There is a good prognosis after excision and a very low chance of recurrence.

- Leiomyomas on histology contain intersecting bundles of spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and cigar-shaped nuclei. Immunohistochemistry is positive for smooth muscle actin and desmin. Management is complete surgical excision with rare likelihood of recurrence. [44]

- Osteomas are rare benign osseous tumors that present as a medial canthal mass with ocular pain and swelling and are often congenital. CT shows a well-circumscribed, radiodense lesion, which is highly suggestive of osteoma due to its bony density. Management is by endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy or complete surgical excision. These have a good prognosis with very rare recurrence, and therefore long-term follow-up is not needed. [45][46][47]

Diagnosis

Physical Exam

The workup for a patient with a lacrimal mass and epiphora includes a full history, a complete ophthalmic exam, lacrimal probe and irrigation, and gross examination of the nose. If concerned, a multidisciplinary approach with ENT preforming an endoscopy can help determine management.

Given that a mass may not be appreciated during early stages, diagnosis may be difficult to differentiate from chronic dacryocystitis.[4] On examination, a lacrimal sac pathologic entity can present with swelling from the medial canthal tendon inferiorly, is typically firm in consistency, and is usually adherent to the underlying structures.

Differential Diagnosis

- Dacryocystitis

- Dacryocystocele

- Mucocele

- Nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- Orbital tumor

- Keratoconjunctivitis

Imaging

Imaging can aid in diagnosis, determining extent of disease, and for surgical preparation.

- CT of the orbit and sinus is helpful for identifying changes to bone and invasion through bone while CT dacryocystography of the lacrimal system can be used to demonstrate a lacrimal sac filling defect but does not delineate soft tissue well.

- MRI provides increased visualization of the soft tissue. Examples of lacrimal sac tumors evident on CT and MRI imaging are included below.

- Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of lacrimal sac tumors is not recommended as interpretation of results are difficult and complications include hemorrhage, infection, and inadequate biopsy. Instead, a direct incisional biopsy is recommended for adequate tissue samples.

A careful histopathologic assessment and diagnosis is needed to both confirm tumor type and guide treatment. Once detected, communication with oncology specialists is required to coordinate and assess the necessity of a metastatic workup. [4][8][26]

Prognosis

The prognosis of lacrimal sac tumors depends on tumor type, malignancy, stage, grade, and the patient’s overall health. However, the overall mortality of malignant lacrimal sac tumors is approximately 38%, with transitional cell carcinoma and melanoma having the worst prognosis. [4]

Management

Benign epithelial or mesenchymal tumors confined to the lacrimal sac are often treated with complete surgical excision and follow-up for recurrence or risk of malignant transformation, such as in adenomas. Medical management is usually not indicated.

In cases of malignancy, complete tumor excision with removal of local periosteum is recommended, as cancer recurrence is believed to be due to the extension of premalignant lesions along the nasolacrimal duct. In cases with radiological evidence of tumors which have spread beyond the lacrimal drainage system, resection of the orbital and nasal walls may also be necessary.

Postoperative radiation and or chemotherapy may be indicated in cases with bony and/or lymphatic invasion, or in cases with systemic disease, both to aid in tumor clearance and to decrease recurrence risk. Lymphoproliferative tumors in the lacrimal sac are often secondary to systemic disease and usually respond to standard systemic treatment. Local radiation therapy may be added to decrease mass symptoms, but surgical intervention is typically not indicated.

Recurrent tumors often require additional surgical intervention and occasionally palliative radiation therapy.[4][8][48] Patients should be managed by a multidisciplinary team with both short- and long-term monitoring, as recurrence and metastasis can occur years after initial management.

References

- ↑ Ashton N, Choyce DP, Fison LG. Carcinoma of the lacrimal sac. Br J Ophthalmol.1951;35:366-376.

- ↑ Radnot M, Gall J. Tumors of the lacrimal sac. Ophthalmologica.1966;151: 2-22.

- ↑ Stefanyszyn MA, Hidayat AA, Pe’er JJ, et al. Lacrimal sac tumors. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg.1994;10:169-184.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Krishna Y, Coupland SE. Lacrimal Sac Tumors--A Review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2017;6(2):173–178. doi:10.22608/APO.201713

- ↑ Elner VM, Burnstine MA, Goodman ML, Dortzbach RK. Inverted Papillomas that Invade the Orbit. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(9):1178-83.

- ↑ Newell FW. The lacrimal apparatus. In: Ophthalmology: Principles and Concepts, 6th, CV Mosby, St. Louis 1986. p.254.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ramberg I, Toft PB, Heegaard S. Carcinomas of the lacrimal drainage system. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2020;65(6):691-707. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2020.04.001

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kim HJ, Shields CL, Langer PD. Lacrimal sac tumors: diagnosis and treatment. In: Black EH, Nesi FA, Cavana CJ, et al, eds. Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New York: Springer; 2012: 609-614.

- ↑ Schaefer DP. Acquired causes of lacrimal system obstructions. In: Black EH, Nesi FA, Cavana CJ, et al, eds. Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New York: Springer; 2012:609-614.

- ↑ Vahdani K, Rose GE. Long-Term Outcome for Primary Papillomas of the Lacrimal Drainage System. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;40(5):538-543. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000002636

- ↑ Arosio AD, Valentini M, Canevari FR, et al. Endoscopic Endonasal Prelacrimal Approach: Radiological Considerations, Morbidity, and Outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(8):1715-1721. doi:10.1002/lary.29330

- ↑ Nagendran S, Alsamnan M, Strianese D, Malhotra R. Ectopic Lacrimal Gland Tissue: A Systematic Review. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36(6):540-544. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001621

- ↑ Baredes S, Ludwin DB, Troublefield YL, Langer PD, Mirani N. Adenocarcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma of the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(6):940-942. doi:10.1097/00005537-200306000-00005

- ↑ Domanski H, Ljungberg O, Andersson LO, Schele B. Oxyphil cell adenoma (oncocytoma) of the lacrimal sac. Review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1994;72(3):393-396. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1994.tb02782.x

- ↑ Mikkelsen LH, Andreasen S, Melchior LC, et al. Genomic and immunohistochemical characterisation of a lacrimal gland oncocytoma and review of literature. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(4):4176-4182. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.6713

- ↑ Valenzuela AA, McNab AA, Selva D, O’Donnell BA, Whitehead KJ, Sullivan TJ. Clinical features and management of tumors affecting the lacrimal drainage apparatus. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(2):96-101. doi:10.1097/01.iop.0000198457.71173.7b

- ↑ Eweiss AZ, Lund VJ, Jay A, Rose G. Transitional cell tumours of the lacrimal drainage apparatus. Rhinology. 2013;51(4):349-354. doi:10.4193/Rhino13.016

- ↑ Miller HV, Siddens JD. Rare transitional cell carcinoma of the lacrimal sac. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020;20:100899. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100899

- ↑ Nomura T, Maki D, Matsumoto F, Mori T, Yoshimoto S. A rare case of coexisting lacrimal sac adenocarcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97(10-11):E32-E35.

- ↑ Takizawa D, Ohnishi K, Hiratsuka K, et al. Primary adenocarcinoma of the lacrimal sac with 5-year recurrence-free survival after radiation therapy alone: a case report. Int Canc Conf J. 2025;14(2):124-130. doi:10.1007/s13691-025-00747-0

- ↑ Zhang AS, Selva D, Tong JY, James C, Le H, Psaltis AJ. Mucosal Spread of Sinonasal Adenocarcinoma into the Nasolacrimal Duct Without Bony Erosion of the Nasolacrimal Canal: A Case Report. Ophthalmic Plast

- ↑ Mudhar HS, Tan JHY, Wagner BE, Salvi SM. Lacrimal sac ciliated HPV16 positive, adenosquamous carcinoma-A case report of a unique histological variant at this site and a review of the literature. Orbit. 2024;43(3):369-374. doi:10.1080/01676830.2022.2145613

- ↑ Chandrakapure D, Sachdeva K, Sachdeva N. Primary Mucinous Eccrine Carcinoma in Nasomaxillary Region: a Rare Case Report and Management Insights. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;76(2):1984-1987. doi:10.1007/s12070-023-04312-0

- ↑ Font RL, Smith SL, Bryan RG. Malignant Epithelial Tumors of the Lacrimal Gland: A Clinicopathologic Study of 21 Cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(5):613-616. doi:10.1001/archopht.116.5.613

- ↑ Noh JM, Lee E, Ahn YC, et al. Clinical significance of post-surgical residual tumor burden and radiation therapy in treating patients with lacrimal adenoid cystic carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):60639-60646. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.10259

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Yip CC, Bartley GB, Habermann TM, et al. Involvement of the lacrimal drainage system by leukemia or lymphoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg.2002;18:242-246.

- ↑ Zhong Q, Yan Y, Li S. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the lacrimal gland: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(21):e38303. doi:10.1097/MD.000000000003830

- ↑ Vest SD, Mikkelsen LH, Holm F, et al. Lymphoma of the Lacrimal Gland - An International Multicenter Retrospective Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;219:107-120. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2020.06.015

- ↑ Rasmussen PK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma of the ocular adnexal region, and lymphoma of the lacrimal gland: an investigation of clinical and histopathological features. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91 Thesis 5:1-27. doi:10.1111/aos.12189

- ↑ Kim J, Kim J, Baek S. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Arising in the Lacrimal Sac. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33(1):e19-e21. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000007861

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Delestre F, Blanche P, Bouayed E, et al. Ophthalmic involvement of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A systematic review of 123 cases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2021;66(1):124-131. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2020.05.001

- ↑ Ren M, Zeng JH, Luo QL, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of lacrimal sac. Int J Ophthalmol.2014;7:1069-1070.

- ↑ Jakobiec FA, Stagner AM, Sutula FC, Freitag SK, Yoon MK. Pigmentation of the Lacrimal Sac Epithelium. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;32(6):415–423. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000541

- ↑ Lee HM, Kang HJ, Choi G, et al. Two cases of primary malignant melanoma of the lacrimal sac. Head Neck. 2001;23(9):809-813. doi:10.1002/hed.1116

- ↑ Vinciguerra A, Rampi A, Giordano Resti A, Barbieri D, Bussi M, Trimarchi M. Melanoma of the lacrimal drainage system: A systematic review. Head Neck. 2021;43(7):2240-2252. doi:10.1002/hed.26705

- ↑ Pe’er JJ, Stefanyszyn M, Hidayat AA. Non epithelial tumors of the lacrimal sac. Am J Ophthalmol.1994;118:650-658.

- ↑ Anderson NG, Wojno TH, Grossniklaus HE. Clinicopathologic findings from lacrimal sac biopsy specimens obtained during dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg.2003;19:173-176.

- ↑ Choi G, Lee U, Won NH. Fibrous histiocytoma of the lacrimal sac. Head Neck. 1997;19(1):72-75. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199701)19:1<72::aid-hed14>3.0.co;2-t

- ↑ Santamaria JA, Gallagher CF, Mehta A, Davies BW. Fibrous Histiocytoma of the Lacrimal Sac in an 11-Year-Old Male. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34(3):e90-e91. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001086

- ↑ Maharaj ASR, Lee S, Yen MT. Fibromyxoma masquerading as dacryocystitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(4):e95-96. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182368417

- ↑ Leroux K, den Bakker MA, Paridaens D. Acquired capillary hemangioma in the lacrimal sac region. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(5):873-875. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2006.05.052

- ↑ Roth SI, August CZ, Lissner GS, O’Grady RB. Hemangiopericytoma of the lacrimal sac. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(6):925-927. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32201-2

- ↑ Jung WS, Ahn KJ, Park MR, et al. The radiological spectrum of orbital pathologies that involve the lacrimal gland and the lacrimal fossa. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8(4):336-342. doi:10.3348/kjr.2007.8.4.336

- ↑ Korn BS, Glasgow BJ, Kikkawa DO. Epiphora as a presenting sign of angioleiomyoma of the lacrimal sac. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(6):490-492. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e318158edb4

- ↑ Kim JY, Kwon JH. An isolated nasolacrimal duct osteoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(4):e319-320. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182869f57

- ↑ Knani L, Oueslati M, Ben Abdessalem N, et al. Isolated congenital osteoma cutis of the lateral canthus. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2022;45(9):e417-e418. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2022.01.024

- ↑ Najmi H, Aleid S, Badghaish F, Alnashwan Y. Congenital solitary osseous choristoma of the left lateral canthus: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024;24(1):140. doi:10.1186/s12886-024-03403-y

- ↑ Stokes DP, Flanagan JC. Dacryocystectomy for tumors of the lacrimal sac. Ophthalmic Surg.1977;8:85-90.