Scar Assessment Scales in Oculoplastic Surgery

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Scar assessment is a critical outcome measure in oculoplastic surgery, where periocular scars occur in uniquely thin, mobile, and cosmetically sensitive tissue. Even subtle scar irregularities in this region can influence eyelid function, facial expression, and patient satisfaction. Although multiple validated scar assessment instruments are widely used in plastic surgery and dermatology, none were specifically developed to capture the functional, dynamic, and aesthetic considerations unique to the eyelids and periocular region. Nevertheless, several of these tools have been applied in periocular contexts, providing insight into their feasibility, strengths, and limitations. This review synthesizes existing scar assessment scales and objective technologies, with a focus on their applicability to periocular scars, to guide clinicians and researchers in selecting appropriate outcome measures for oculoplastic practice.

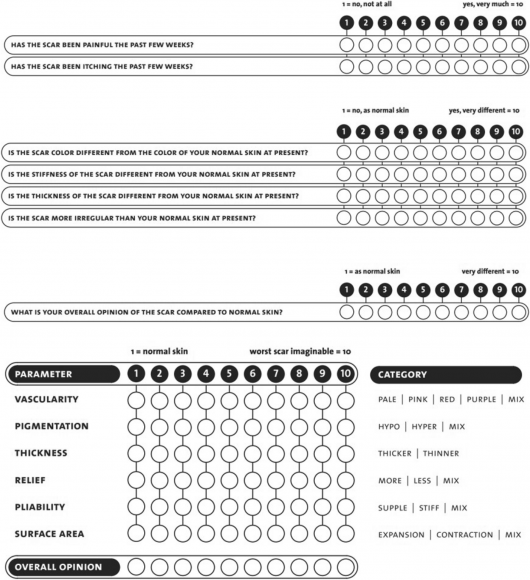

Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale

Introduced in 2004, the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) was the first validated instrument to incorporate the patient’s perspective in scar assessment.[1] The scale consists of two complementary components: the Patient Scale and Observer Scale which respectively assesses the patient and clinician perspectives of scar quality (the visual, tactile and sensory characteristics of a scar).[2]

The Patient Scar Assessment Scale (PSAS) assesses six patient-reported parameters: pain, itching, color, stiffness, thickness, and irregularity, using a 10-point scale for each item (Figure 1).[3]

The Observer Scar Assessment Scale (OSAS) evaluates six parameters: vascularity, pigmentation, thickness, relief, pliability, and surface area. Each domain is also scored on the 10-point scale, with a total score ranging from 6 to 60 (lower scores indicating better outcomes).

A key limitation of earlier POSAS versions was that the Patient Scale was developed without direct patient input, potentially limiting its ability to fully capture patient-perceived scar symptoms. To address this point, a third version of the POSAS (POSAS 3.0) was developed.[2] Compared with prior versions, the POSAS 3.0 Patient Scale:

- Expands the number of items from 6 to 17

- Increases sensory domains from 2 items (pain and itchiness) to 11 sensory items[4]

POSAS 3.0 consists of 2 scales, with each item in the scales scored from 1 (normal skin) to 5 (worst imaginable scar):

- Patient Scale: color, shininess, raised/sunken scar, hardness, irregularity, sensitiveness, numbness, pain, shooting sensation, burning sensation, itch, tingling, scar tightness at rest, tightness during movement, fragility, dryness, and overall opinion of the severity of the scar

- Observer Scale: vascularity, pigmentation, surface level, surface texture, firmness, adhering, tension, and overall opinion of the visual and tactile characteristics of the scar

The Patient Scale and the Observer Scale are two separate instruments that measure scar quality from different perspectives, and, therefore, are complementary to each other. The sum score of both instruments provides no additional meaning.[5]

Ocular Applications of POSAS

As POSAS 3.0 was recently developed, its use is underexplored; however, POSAS 2.0 has been studied extensively, and while its applicability to ocular scars is still limited, existing periocular studies support its feasibility and potential validity in this anatomically distinct region.

A retrospective review of 67 patients that underwent upper blepharoplasty reported an observer average of 11.26 points (almost imperceptible scar).[6] The researchers divided patients into three groups based on where the scar lay relative to the lower eyelid crease/ridge:

- Group A: ≥ 2 mm above the crease/ridge

- Group B: within the crease/ridge to 2 mm above

- Group C: within the crease/ridge to 2 mm below

Group B had the lowest (best) POSAS scores (mean 20.9 ± 2.4), compared with Group A (22.7 ± 8.0) and C (32.5 ± 4.1).

POSAS score was positively correlated with the distance between eyelid margin and scar (DMS), meaning the farther the scar from the eyelid margin, the worse the scar quality (higher POSAS).[7]

Interpretation: Scars that are farther from the eyelid margin are more visible or less well hidden by the eyelid crease, so observers and patients tend to rate them worse.

Strengths:

- Dual perspective: POSAS uniquely captures both objective and subjective experiences, which is crucial in cosmetically sensitive areas like the periocular region.

- Developed for all scar types, whereas other assessments are specific to surgery, burn, and trauma scars.[2]

- Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) values are interpreted as follows: poor (<0.50), moderate (≥0.50 to <0.75), good (≥0.75 to <0.90), and excellent (≥0.90). POSAS 3.0 demonstrates excellent reliability, with interobserver and intraobserver ICCs exceeding 0.90 for both the Observer and Patient subscales.[8]

Limitations:

- POSAS 3.0 is a recently introduced instrument, and while its development was rigorous, large-scale independent validation studies are still limited.

- Although POSAS 3.0 incorporated patient input, patients with periocular scars were not specifically targeted as a distinct subgroup during development, which means that eyelid-specific concerns such as visibility during blinking, social gaze, and facial expression asymmetry remain underrepresented and unaddressed.

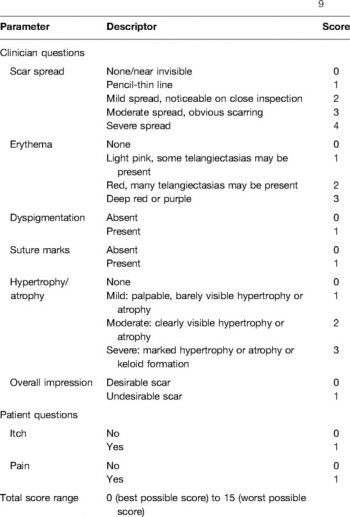

Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating

The Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating (SCAR) Scale is a tool specifically designed for postoperative linear scars, developed to assess cosmesis in live patients and photographs. It consists of 6 observer-scored items and 2 patient-scored items, with scores ranging from 0 (best possible scar) to 15 (worst possible scar) (Figure 2):

- Clinician items: scar spread, erythema, dyspigmentation, hypertrophy/atrophy, suture marks/track marks, overall impression

- Patient items: itch (yes/no), pain (yes/no)

Ocular Applications of SCAR

A recent retrospective case series (6 patients) of periocular skin defects repaired using acellular fish skin grafts after Mohs excision of basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma reported a mean SCAR score of 4.2 (range: 3-7).[9]

This case series is notable for its use of fish skin grafts, a novel biologic scaffold for wound healing, and demonstrates their potential to achieve favorable wound healing and cosmetic outcomes as indicated by the low mean SCAR score.

Strengths:

- Most oculoplastic procedures (blepharoplasty, ptosis repair, Mohs closures) produce short, linear scars along relaxed skin tension lines, which directly matches the scar morphology SCAR was designed to assess.

- The demonstrated equivalence between photographic and live scar assessment is particularly advantageous in allowing remote grading without requiring repeated in-person visits that may require patients to travel long distances.[10]

Limitations:

- The SCAR scale's focus on linear postoperative scars limits its applicability to other scar types. In ocular surgery, this may be less suited for complex scars, such as Z-plasties, flaps, or multi-directional incisions common in larger reconstructions.

- Binary outcomes may sacrifice the ability to capture subtle changes in scar quality.

- The limited patient component does not comprehensively capture other important subjective experiences.

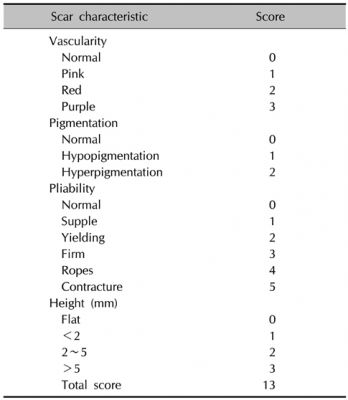

Vancouver Scar Scale

The Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) is a widely used observer-rated tool for assessing scar quality, originally developed for burn scars. The VSS assesses four parameters: vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, and height/thickness of skin scars. The maximum score possible is 13, indicating the worst possible scar result, with a score of 0 indicating normal skin (Figure 3).[11]

Ocular Applications of VSS

In a prospective randomized study of zygomaticomaxillary fracture repair, 44 patients underwent repair via an upper blepharoplasty approach, while 44 patients were treated using a supraorbital eyebrow approach.[12]

- Upper blepharoplasty approach: 10-mm curvilinear incision is made superior to the upper eyelid margin, extending from the mid-pupillary line to the lateral orbital rim.

- Supraorbital eyebrow approach: a 2-cm incision is placed within the lateral eyebrow, oriented parallel to the hair shafts and carried down to the periosteum.

- At 6 months postoperatively, 34 patients (77.3%) in the SE group demonstrated mild scarring (VSS score 1-5), while 10 patients (22.7%) had moderate scarring (VSS score 6-10). In contrast, all patients in the UB group exhibited mild scarring (VSS score 1-5).[12]

A mild VSS score (1–5) reflects minimal scar height, low vascularity, satisfactory pigmentation, and good pliability, which translates into scars that are less visible and cosmetically more acceptable.

The findings suggest that the upper blepharoplasty approach, which follows natural eyelid crease lines, yields more cosmetically favorable scars than the supraorbital eyebrow incision, justifying its increasing use for orbital access in fracture management.

Strengths:

- Assigns differential weighting to key scar characteristics, reflecting the greater clinical relevance of features such as vascularity. This weighted structure emphasizes scar components that disproportionately affect scar severity and treatment decision-making.[13]

Limitations:

- VSS completely lacks patient-reported components.

- The VSS categorizes pigmentation as hypopigmented, normal, and hyperpigmented but objective measurements reveal that pigmentation exists on a continuous spectrum that cannot be adequately captured by these broad categories.[14]

Manchester Scar Scale

Similar to SCAR, the Manchester Scar Scale (MSS) is an observer-rated tool developed specifically for assessing linear scars. The MSS evaluates the following parameters: color, matte versus shiny, contour, distortion, and texture. A score of 5 corresponds to the best scar outcome, and a score of 18 corresponds to the worst possible scar outcome (Figure 4).[15]

Ocular Applications of MSS

One study applied the MSS to compare postoperative scars between patients who had upper eyelid blepharoplasty versus those who had external dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR).

- Blepharoplasty scars demonstrated higher MSS scores (worse scar outcomes) than DCR scars.

- MSS scores showed a significant correlation with patient dissatisfaction, indicating that worse observer-rated appearance aligned with poorer patient perception.

Despite blepharoplasty incisions being placed in natural eyelid creases, subtle differences in contour irregularity, texture, or color mismatch were detectable by MSS. This suggests that even cosmetically “concealed” eyelid scars can still be meaningfully differentiated.

In another study, MSS was used to compare scars from two different upper eyelid blepharoplasty suture techniques: interrupted versus running sutures.

- Interrupted sutures produced significantly lower (better) overall MSS scores than running sutures at both 1 month and 3 months after upper eyelid blepharoplasty.

Running sutures can lead to tissue overlap and increased tissue prominence, which may adversely affect wound healing. In contrast, the superior outcomes observed with interrupted sutures in eyelid closure may be attributed to improved tissue approximation and thus associated with more favorable scar formation following upper eyelid blepharoplasty.[16]

Strengths:

- Emphasizes item descriptors based on clinical relevance. For example, scar height is assessed using contour-based descriptors (flush, slightly raised or indented, hypertrophic, or keloid) rather than numerical measurements.

- Addresses limitations of color assessment by incorporating a single item that evaluates contrast with the surrounding skin, rather than separating color into multiple components such as pigmentation or vascularity.

Limitations:

- Does not differentially weight scar characteristics, treating all features as equally important despite clinical evidence that certain characteristics (like hypertrophy and spread) have greater impact on scar quality.

- Fails to include scar spread, perhaps the most important measure of linear scar quality.[11]

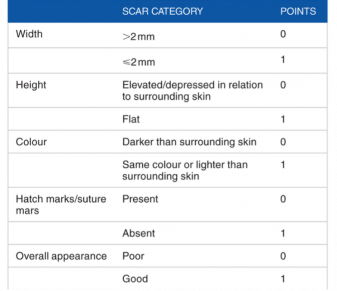

Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale

The Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale (SBSES) is another observer-rated tool designed to assess postoperative scars. The SBSES evaluates 5 scar characteristics: width, height, color, suture or staple marks, and overall appearance. It has a simple scoring system ranging from 0 (worst) to 5 (best) to rate scar quality (Figure 5).[17]

Ocular Applications of SBSES

SBSES was used to rate medial canthal scars following epicanthoplasty incorporating blepharoplasty (scar hiding epicanthoplasty) versus conventional Y-V epicanthoplasty (involves making a Y-shaped incision in the medial canthal region and closing it in a V-shaped fashion) in East Asian populations.[18]

- Scar-hiding epicanthoplasty achieved significantly higher (better) SBSES scores than the conventional Y-V procedure at both 3 and 6 months postoperatively.

The scar-hiding epicanthoplasty technique achieves measurably better medial canthal scar outcomes and greater patient satisfaction than the conventional Y-V approach, making it a clinically preferable option in epicanthal surgery.[18]

Strengths:

- Similar to SCAR, SBSES allows photographic evaluation

Limitations:

- Not designed for long-term scar assessment

- Does not include patient assessment

Colorimetry

Colorimetry is a non-invasive technique that objectively measures skin and scar color by quantifying light reflection at specific wavelengths, providing numerical values for erythema (redness/vascularity) and melanin (pigmentation). Colorimetric devices use either tristimulus colorimeters or narrow-band spectrophotometers.[19][20]

Tristimulus colorimeters such as the Minolta Chromameter and DSM II ColorMeter compute the intensity of light reflected from skin using the CIELAB color space. This system expresses color as three values: L* (lightness, ranging from black to white), a* (red-green axis), and b* (yellow-blue axis).[21]

Narrow-band spectrophotometers like the Mexameter and DermaSpectrometer measure light reflection at wavelengths specific to hemoglobin (for erythema/vascularity) and melanin (for pigmentation). These devices generate separate erythema and melanin indices that quantify the concentration of these chromophores in the tissue.[20]

Three-Dimensional Photography

Three-dimensional (3D) photography, also known as 3D stereophotogrammetry, is a non-invasive imaging technique that captures the surface topography of scars to provide objective, quantitative measurements of scar parameters including volume, surface area, height/depth, and surface irregularity.[22][23]

Image Acquisition

The technology uses either passive stereophotogrammetry or active stereophotogrammetry.

Passive stereophotogrammetry:

- Multiple cameras positioned at different angles simultaneously capture images of the scar.

- The parallax (differences in perspective) between these images are then used to calculate depth and create a 3D model.[24]

Active stereophotogrammetry:

- Multiple cameras project structured light patterns (such as grids or stripes) onto the skin surface, then capture how these patterns deform over the scar's topography.

- The distortion of the projected pattern provides direct depth information that the software uses to construct the 3D model.[24]

Measurement

Volume

- The analysis software defines a region of interest (the scar area) and a reference surface (a flat plane/normal skin).

- Volume is calculated as the space between the scar surface and the reference surface:

- For hypertrophic scars and keloids, this measures positive volume (elevation above normal skin)

- For atrophic scars like acne scars, it measures negative volume (depression below normal skin)

Height and Depth

- Height or depth is measured as the vertical (z-axis) distance between the scar surface and the reference surface.

Surface Irregularity

- Each point on the scar surface is compared to the reference surface.

- The vertical distance (z-axis) at each point is calculated.

- The software analyzes how much these distances vary across the scar:

- In a smooth scar, most points lie close to the reference surface and would have a low irregularity score

- On the contrary, in an uneven scar, there’d be a high irregularity score

Surface Area

- After 3D reconstruction, the scar surface is represented as a mesh of tiny triangles.

- Surface area is calculated by adding up the area of all triangles within the selected scar region.

Key Takeaways

- Even though a number of scar assessment scales have been applied to periocular scars, they generally fail to address the functional and dynamic eyelid-specific outcomes, such as blink mechanics, visual acuity, and lid symmetry, which are central to patient satisfaction.

- Observer-based scales remain valuable for clinical practicality and aesthetic assessment but should be interpreted with awareness of their limited eyelid-specific metrics.

- Objective technologies such as colorimetry and 3D photography are useful complementary tools in that they help overcome the subjectivity inherent in visual scar assessment scales.

- For instance, studies have found that 27% of scars were incorrectly classified as "hyperpigmented" by observers despite showing low melanin measurements on devices.[25]

- Scar assessment scales are not only research tools but can serve as guides for clinical management.

References

- ↑ Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FRH, Botman YAM, et al. The Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale: A Reliable and Feasible Tool for Scar Evaluation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;113(7):1960. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000122207.28773.56

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Carrière ME, Tyack Z, Westerman MJ, et al. From qualitative data to a measurement instrument: A clarification and elaboration of choices made in the development of the Patient Scale of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) 3.0. Burns. 2023;49(7):1541-1556. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2023.02.009

- ↑ O’Connell DA, Diamond C, Seikaly H, Harris JR. Objective and Subjective Scar Aesthetics in Minimal Access vs Conventional Access Parathyroidectomy and Thyroidectomy Surgical Procedures: A Paired Cohort Study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(1):85-93. doi:10.1001/archotol.134.1.85

- ↑ Carrière ME, Mokkink LB, Tyack Z, et al. Development of the Patient Scale of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) 3.0: a qualitative study. Qual Life Res. 2023;32(2):583-592. doi:10.1007/s11136-022-03244-6

- ↑ User instructions POSAS 3.0. POSAS. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.posas.nl/instructions/

- ↑ Gómez VHA, Espinoza JAG, López JCM, et al. Upper Blepharoplasty Scar and Patient Satisfaction Evaluation in a Plastic Surgery Center in Mexico. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines. 2020;8(6):77-88. doi:10.4236/jbm.2020.86008

- ↑ Oh SJ, Kim KS, Choi JH, Hwang JH, Lee SY. Scar formation after lower eyelid incision for reconstruction of the inferior orbital wall related to the lower eyelid crease or ridge in Asians. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2021;22(6):310-318. doi:10.7181/acfs.2021.00521

- ↑ Vercelli S, Razza S, Laurelli D, Negrini F, Bravini E, Ferriero G. Cross-cultural adaptation, validation, and reliability of the Italian version of the patient and observer scar assessment scale (POSAS-I) version 3.0. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2025;0(0):1-14. doi:10.1080/09638288.2025.2582195

- ↑ Wang D, Maliakkal J, Sadat O, Codrea V, Nguyen J. Acellular Fish Skin Grafts for Treatment of Periocular Skin Defects. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2024;40(6):681. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000002699

- ↑ Kantor J. Reliability and Photographic Equivalency of the Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating (SCAR) Scale, an Outcome Measure for Postoperative Scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(1):55-60. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3757

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Chae JK, Kim JH, Kim EJ, Park K. Values of a Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale to Evaluate the Facial Skin Graft Scar. Annals of Dermatology. 2016;28(5):615-623. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.5.615

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mirza HH, Ahmed F, Rahber M, et al. Post-Operative Scar Comparison With Supraorbital Eyebrow and Upper Blepharoplasty Approach in the Management of Zygomaticomaxillary Complex Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2022;16(4):268-274. doi:10.1177/19433875221124406

- ↑ Erkan Pota Ç, Bilgiç A, Çetinkaya Yaprak A, İlhan HD, Kahraman U. Evaluation of periocular scars after blepharoplasty and external dacryocystorhinostomy according to Manchester and modified Vancouver scar score. Int Ophthalmol. 2025;45(1):190. doi:10.1007/s10792-025-03567-6

- ↑ Gankande TU, Duke JM, Wood FM, Wallace HJ. Interpretation of the DermaLab Combo® pigmentation and vascularity measurements in burn scar assessment: An exploratory analysis. Burns. 2015;41(6):1176-1185. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2015.01.012

- ↑ Fearmonti R, Bond J, Erdmann D, Levinson H. A Review of Scar Scales and Scar Measuring Devices. Eplasty. 2010;10:e43.

- ↑ Aydemir E, Kiziltoprak H, Aydemir GA. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes of Upper Eyelid Blepharoplasty Using Two Different Suture Techniques. Beyoglu Eye J. 2022;7(1):18-24. doi:10.14744/bej.2021.36349

- ↑ Singer AJ, Arora B, Dagum A, Valentine S, Hollander JE. Development and Validation of a Novel Scar Evaluation Scale. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;120(7):1892. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000287275.15511.10

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Jia FY, Xiong L, Qiu LH, Yan J, Chen J, Gang Yi C. Blepharoplasty incorporating epicanthoplasty using the scar-hiding procedure. clinical-practice. 2018;15(2). doi:10.4172/clinical-practice.1000389

- ↑ Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FRH, Botman YAM, Kreis RW, Middelkoop E, van Zuijlen PPM. Colour evaluation in scars: tristimulus colorimeter, narrow-band simple reflectance meter or subjective evaluation? Burns. 2004;30(2):103-107. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2003.09.029

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 van der Wal M, Bloemen M, Verhaegen P, et al. Objective color measurements: clinimetric performance of three devices on normal skin and scar tissue. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34(3):e187-194. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e318264bf7d

- ↑ Ly BCK, Dyer EB, Feig JL, Chien AL, Del Bino S. Research Techniques Made Simple: Cutaneous Colorimetry: A Reliable Technique for Objective Skin Color Measurement. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(1):3-12.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.11.003

- ↑ Stekelenburg CM, Jaspers MEH, Niessen FB, et al. In a clinimetric analysis, 3D stereophotogrammetry was found to be reliable and valid for measuring scar volume in clinical research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(7):782-787. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.02.014

- ↑ Peake M, Pan K, Rotatori RM, et al. Incorporation of 3D stereophotogrammetry as a reliable method for assessing scar volume in standard clinical practice. Burns. 2019;45(7):1614-1620. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2019.05.005

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Singh P, Bornstein MM, Hsung RTC, et al. Frontiers in Three-Dimensional Surface Imaging Systems for 3D Face Acquisition in Craniofacial Research and Practice: An Updated Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2024;14(4). doi:10.3390/diagnostics14040423

- ↑ Bagheri M, von Kohout M, Fuchs PC, et al. How to evaluate scar colour after burn injuries - A clinical comparison of the Mexameter® and the subjective scar assessment (POSAS/VSS). Burns. 2024;50(3):691-701. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2023.11.010