Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE) is an inflammatory chorioretinopathy first described by Gass in 1968.[1] It is classified among the White Dot Syndromes and is uncommon, with an estimated incidence of approximately 0.15 cases per 100,000 persons.[2][3][4] Patients most frequently present with blurred vision accompanied by central or paracentral scotomas, often following a flu-like prodrome and headache. Additional visual symptoms may include photopsias and metamorphopsia. APMPPE is typically bilateral, affects women and men equally, and most commonly occurs in the second to fourth decades of life.

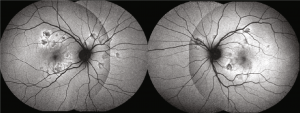

On dilated fundus examination, the characteristic finding is multiple creamy yellow or gray-white placoid lesions at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the posterior pole.[5] The disease course is often self-limited, with visual symptoms resolving within 4 to 8 weeks. There is no consensus regarding treatment; however, corticosteroids have been used to hasten visual recovery, particularly in cases with macular involvement or neurological symptoms due to the risk of associated cerebral vasculitis.[6] Recurrence is rare but is typically associated with a worse prognosis, and a diagnosis of relentless placoid chorioretinitis should be considered if disease activity persists beyond six months.[3]

Etiology

Several hypotheses have been proposed regarding the underlying etiology of APMPPE. In his original 1968 description, Gass coined the term "pigment epitheliopathy" to reflect his belief that the retinal pigment epithelium was the primary tissue affected.[1] With the subsequent development of fundus fluorescein angiography, Van Buskirk et al[7] and Deutman et al[8] suggested choriocapillaris ischemia as the more likely primary pathogenic mechanism. More recently, Steptoe et al proposed a direct neurotropic infectious etiology.[9] In contrast to a primary choriocapillaris pathology, their findings demonstrated that changes within the retinal nerve fiber layer precede alterations in the outer retina, along with the presence of axonal spheroids along the unmyelinated photoreceptor axons comprising the Henle fiber layer.[9]

Risk Factors

Approximately 33% of patients report a preceding viral or flu-like illness prior to the onset of APMPPE symptoms.[1][10] The condition has been associated with a wide range of systemic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, including erythema nodosum, sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, scleritis, thyroiditis, nephritis, ulcerative colitis, and central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis, as well as with post-vaccination states.[11][12] Reported implicated vaccines include polio, tetanus, varicella, hepatitis A and B, meningococcal C, yellow fever, typhoid, and influenza.[13] Infectious associations have also been described, including group A Streptococcus, adenovirus type 5, influenza, coxsackie B virus, hepatitis B, Lyme disease, mumps, and tuberculosis. Genetic susceptibility may contribute to disease risk, as associations with specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes, including HLA-B7 and HLA-DR2, have been reported.[14]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathogenesis of APMPPE remains controversial. An earlier theory proposed by Gass suggests that primary inflammation of the outer retina and RPE gives rise to the characteristic placoid lesions observed in APMPPE.[1] A second theory proposed by Van Buskirk is an occlusive vasculitis, potentially mediated by inflammatory or autoimmune mechanisms, affects the choriocapillaris, leading to hypoperfusion and ischemia of the RPE and photoreceptors.[7] This ischemic injury to the outer retina and RPE subsequently produces the characteristic placoid appearance.[15] In later stages, inflammation of the choroid and retina may result in RPE atrophy and hyperpigmentation.[10] The prevailing theory supports primary involvement of the choriocapillaris with secondary injury to the RPE and outer retina. The ultimate outcome of the disease process is atrophy of the choriocapillaris, RPE, and photoreceptors. Notably, some authors have suggested that the term choroidopathy may be more appropriate than epitheliopathy to reflect the primary site of pathology.[6]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of APMPPE is primarily based on clinical presentation and fundoscopic examination, with many studies also advocating for a multimodal imaging approach.[3][6][15] According to a study by the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group, informatics and machine learning based consensus classification criteria for APMPPE include the presence of "choroidal lesions with a plaque-like or placoid appearance" and "characteristic imaging on fluorescein angiography (lesions block early and stain late diffusely)."[16] The Multimodal Imaging in Uveitis (MUV) Taskforce Report further emphasizes important diagnostic features, including the detection of outer retinal hyper-reflectivity on optical coherence tomography (OCT) and the evaluation of choriocapillaris involvement using optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), fundus autofluorescence (FAF), fluorescein angiography (FA), and indocyanine green angiography (ICG).[17]

History

Patients with APMPPE typically experience a rapid onset of blurred vision, often accompanied by central and paracentral scotomas. Photopsias and metamorphopsia may precede the visual loss.[5] Symptoms are usually bilateral but asymmetric and can develop several days apart. Visual acuity ranges from 20/40 to counting fingers, depending on the degree of foveal involvement. Headache and other neurological manifestations, including sensorineural hearing loss, may occur and sometimes appear months after the ocular presentation.[18] All patients with a new diagnosis of APMPPE should undergo a comprehensive neurologic and systemic evaluation to assess for CNS vasculitis and other associated systemic conditions, as APMPPE-associated cerebral vasculitis can be life-threatening. Additional CNS disorders occasionally reported in association with APMPPE include optic neuritis, peripheral vestibular disorders, meningoencephalitis, seizures, venous sinus thrombosis, intracerebral hemorrhage, and cerebrovascular events such as stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA).[18][19]

Physical Examination

Anterior segment examination is usually unremarkable, although anterior uveitis may be present, and mild vitritis occurs in approximately 50% of cases.[10] Fundoscopic evaluation typically reveals multiple bilateral creamy yellow-white placoid lesions at the level of the RPE and choroid, each measuring 1–2 disc diameters, predominantly located posterior to the equator within the posterior pole. These lesions gradually fade over 1–2 weeks, though new lesions may appear peripherally up to three weeks after onset, often in a radial or linear pattern. Papillitis can occur, but cystoid macular edema (CME) is uncommon. Older lesions are replaced by RPE atrophy or hyperpigmentation. Rarely, APMPPE has been associated with retinal vasculitis, vein occlusion, subhyaloid hemorrhage, retinal neovascularization, exudative retinal detachment, and choroidal neovascular membrane formation.

Diagnostic Procedures

No specific laboratory tests are available to confirm the diagnosis of APMPPE. Diagnosis typically relies on multimodal imaging, which may include spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), fundus autofluorescence (FAF), fluorescein angiography (FA), and indocyanine green angiography (ICG).[3][6][15][17] Characteristic findings on these modalities include:

- Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT): Acute lesions show hyperreflectivity extending from the outer plexiform layer to the RPE, usually with preserved retinal thickness.[6] Absence of the ellipsoid zone (EZ) may indicate foveal involvement and correlates with visual acuity loss.[20] During lesion resolution, outer retinal hyperreflectivity diminishes, the EZ reappears, and focal photoreceptor/RPE atrophy may develop.[6][20][21]

- Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA): Acute lesions may demonstrate reduced choriocapillaris flow, while healing lesions show formation of vascular channels with partial flow restoration. The flow deficits in acute lesions may reflect either signal attenuation due to outer retinal and/or RPE thickening or true choriocapillaris hypoperfusion.[15][22]

- Fundus autofluorescence (FAF): Placoid lesions generally appear hypoautofluorescent, often with hyperautofluorescent edges. Hypoautofluorescence at lesion borders may persist even after resolution.[6]

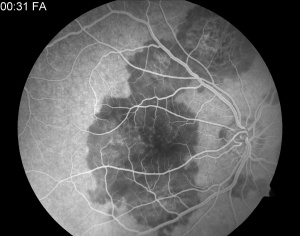

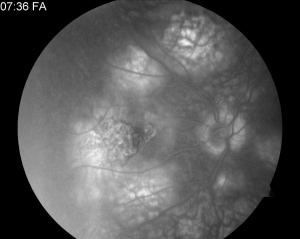

- Fluorescein angiography (FA): Active lesions typically demonstrate early hypofluorescence corresponding to the placoid lesions, followed by late, irregular hyperfluorescent staining.[5] Early hypofluorescence may represent choriocapillaris hypoperfusion or signal attenuation from overlying outer retinal and RPE thickening. Late hyperfluorescence is thought to result from vascular leakage, which resolves in subacute or healed lesions.[22]

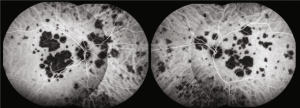

- Indocyanine green angiography (ICG): Active placoid lesions appear hypofluorescent both early and late, reflecting impaired choriocapillaris perfusion. Normalization of the ICG signal may occur as lesions resolve.[5]

- In addition to ocular imaging, CNS evaluation—including brain MRI +/- MRA and, in some cases, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis—should be considered in all newly diagnosed patients to rule out CNS vasculitis.[23]

Differential Diagnosis

- Several other White Dot Syndromes can resemble APMPPE, including:

- Other infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic etiologies such as syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, choroidal metastases, and lymphoma may also present with placoid lesions and should be excluded with appropriate testing when clinically suspected.

Management

General Treatment and Prognosis

APMPPE is generally self-limiting and associated with a favorable visual prognosis, with the majority of patients achieving a visual acuity of better than 20/25.[24] Visual recovery typically occurs within four weeks but may extend up to six months in some cases. Foveal involvement is a significant predictor of poorer visual outcomes.[6] Other atypical features associated with a worse prognosis include age over 60 years, unilateral disease, an interval of six months or more before involvement of the second eye, disease recurrence, and leakage from choroidal veins.[25]

There is currently no consensus on treatment to prevent visual loss in APMPPE. Corticosteroids have been employed and reported to be beneficial, particularly in cases with foveal involvement or associated CNS vasculitis.[6] Some clinicians also choose to initiate steroids even in the absence of these features. In patients with CNS vasculitis, intravenous methylprednisolone followed by an oral steroid taper may be considered.[4] Further studies are needed to clarify optimal dosing, duration, and efficacy of steroid therapy. All patients with newly diagnosed APMPPE should undergo a comprehensive neurologic and systemic evaluation to rule out CNS vasculitis and other associated systemic conditions, particularly autoimmune and infectious disorders outlined in the Risk Factors section.

Recurrent or chronic APMPPE may represent Relentless Placoid Chorioretinitis (RPC), also known as Ampiginous Choroiditis, a condition with features overlapping APMPPE and Serpiginous Choroidopathy. RPC is characterized by a high recurrence rate, prolonged disease activity, and numerous multifocal lesions (>50) scattered throughout the fundus.[3] Correct diagnosis here is important, as the relapses of RPC and SC may warrant treatment with immunomodulatory therapy.[26][27]

Additional Resources

A case with imaging has been presented at https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/the-case-of-aches-and-pains-and-blurry-vision

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Gass JD. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. Aug 1968;80(2):177-185.

- ↑ Abu-Yaghi NE, Hartono SP, Hodge DO, Pulido JS, Bakri SJ. White dot syndromes: a 20-year study of incidence, clinical features, and outcomes. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. Dec 2011;19(6):426-430.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Raven ML, Ringeisen AL, Yonekawa Y, Stem MS, Faia LJ, Gottlieb JL. Multi-modal imaging and anatomic classification of the white dot syndromes. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2017;3:12.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Testi I, Vermeirsch S, Pavesio C. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE). J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2021 Nov 1;11(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12348-021-00263-1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Ma DJ. Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy. In: Yu HG, ed. Inflammatory and Infectious Ocular Disorders. Singapore: Springer; 2020:1-7.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Oliveira MA, Simão J, Martins A, Farinha C. Management of Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy (APMPPE): Insights from Multimodal Imaging with OCTA. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2020;2020:7049168.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Van Buskirk EM, Lessell S, Friedman E. Pigmentary Epitheliopathy and Erythema Nodosum. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85(3):369-372. doi:10.1001/archopht.1971.00990050371025

- ↑ Deutman A, Oosterhuis J, Boen-Tan T, Aan de Kerk A. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy - Pigment epitheliopathy or choriocapillaritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1972;56(12):863-874. doi:10.1136/bjo.56.12.863

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Steptoe PJ, Pearce I, Beare NAV, et al. Proposing a Neurotropic Etiology for Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy and Relentless Placoid Chorioretinitis. Front Ophthalmol 2022;1:802962.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Holt WS, Regan CD, Trempe C. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. Apr 1976;81(4):403-412.

- ↑ Comu S, Verstraeten T, Rinkoff JS, Busis NA. Neurological manifestations of acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Stroke. May 1996;27(5):996-1001.

- ↑ Hernández-Da Mota SE. [Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Case report]. Cir Cir. 2016 Mar-Apr 2016;84(2):135-139.

- ↑ Kraemer LS, Montgomery JR, Baker KM, Colyer MH. ACUTE POSTERIOR MULTIFOCAL PLACOID PIGMENT EPITHELIOPATHY AFTER IMMUNIZATION WITH MULTIPLE VACCINES. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Jan 2020.

- ↑ Wolf MD, Folk JC, Panknen CA, Goeken NE. HLA-B7 and HLA-DR2 antigens and acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. May 1990;108(5):698-700.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Heiferman MJ, Rahmani S, Jampol LM, et al. ACUTE POSTERIOR MULTIFOCAL PLACOID PIGMENT EPITHELIOPATHY ON OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY. Retina. Nov 2017;37(11):2084-2094.

- ↑ Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Classification Criteria for Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Aug;228:174-181.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Carreño E, Maghsoudlou P, Fonollosa A, Leal I, Schlaen A, Abraham AR, Dick AD, Agarwal A, Gangaputra S, Invernizzi A, Fawzi A, Miserocchi E, Agrawal R, Jabs DA, Sarraf D, Gupta V; Multimodal Imaging in Uveitis (MUV) Taskforce. Evidence and Consensus-Based Imaging Guidelines in Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy (APMPPE) - Multimodal imaging in Uveitis (MUV) Taskforce Report 7. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025 Oct;278:38-51.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Maamari RN, Stunkel L, Kung NH, et al. Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy Complicated by Fatal Cerebral Vasculitis. J Neuroophthalmol. Jun 2019;39(2):260-267.

- ↑ Tsuboyama M, Chandler JV, Scharf E, et al. Neurologic Complications of Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy: A Case Series of 4 Patients. Neurohospitalist. Jul 2018;8(3):146-151.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Browne A, Ansari W, Hu M, et al. Quantitative Analysis of Ellipsoid Zone in Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy. Journal of VitreoRetinal Diseases. 2020;4(3):192-201.

- ↑ Scheufele TA, Witkin AJ, Schocket LS, et al. Photoreceptor atrophy in acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy demonstrated by optical coherence tomography. Retina. Dec 2005;25(8):1109-1112.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Desai R, Nesper P, Goldstein DA, Fawzi AA, Jampol LM, Gill M. OCT Angiography Imaging in Serpiginous Choroidopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 04 2018;2(4):351-359.

- ↑ Algahtani H, Alkhotani A, Shirah B. Neurological Manifestations of Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy. J Clin Neurol. 2016 Oct;12(4):460-467. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2016.12.4.460.

- ↑ Fiore T, Iaccheri B, Androudi S, Papadaki TG, Anzaar F, Brazitikos P, D'Amico DJ, Foster CS. Acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy: outcome and visual prognosis. Retina. 2009 Jul-Aug;29(7):994-1001.

- ↑ Pagliarini S, Piguet B, Ffytche TJ, Bird AC. Foveal involvement and lack of visual recovery in APMPPE associated with uncommon features. Eye (Lond). 1995;9 ( Pt 1):42-47.

- ↑ Asano S, Tanaka R, Kawashima H, Kaburaki T. Relentless Placoid Chorioretinitis: A Case Series of Successful Tapering of Systemic Immunosuppressants Achieved with Adalimumab. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2019 Jan-Apr 2019;10(1):145-152.

- ↑ Jyotirmay B, Jafferji SS, Sudharshan S, Kalpana B. Clinical profile, treatment, and visual outcome of ampiginous choroiditis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. Jan 2010;18(1):46-51.