Ocular Manifestations of Hantavirus Infection

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of hantavirus infection, including virology, systemic manifestations, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. It then focuses on the spectrum of ocular manifestations, which range from transient refractive and anterior segment changes to rare but vision-threatening complications. By synthesizing the available ophthalmic literature, this review highlights the importance of recognizing ocular findings that may precede systemic illness and underscores the role of ophthalmologists in facilitating timely multidisciplinary care.

Disease

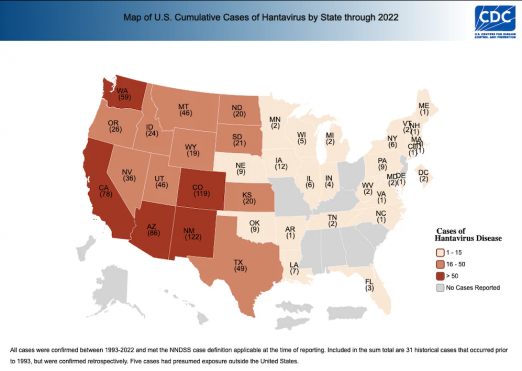

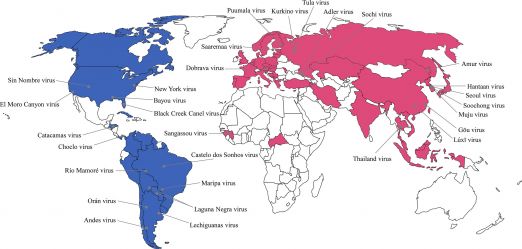

Hantaviruses are enveloped, negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses in the Hantaviridae family, classified as Old World or New World species. Old World viruses (Puumala, Hantaan, Dobrava, Seoul) cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), while New World viruses (Sin Nombre, Andes) cause hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS). Although these syndromes are distinct, they share overlapping clinical and pathologic features.[1][2] The geographic distribution of confirmed hantavirus cases in the United States is shown in Figure 1, while the global distribution of hantavirus strains is illustrated in Figure 2.[3][4]

Systemic Manifestations of Hantavirus

Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome

HFRS (Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome) consists of five stages: the febrile, hypotensive, oliguric, diuretic, and convalescent phases.

- Febrile phase: fever, facial flushing, myalgia, headache, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and blurred vision.[5][6]

- Hypotensive phase: hypotension shock, reflex tachycardia, hematemesis, epistaxis, and hematuria.

- Oliguric phase: oliguria or anuria, peripheral and pulmonary edema; some patients may require hemodialysis.

- Diuretic phase: brisk diuresis (several liters/day) leading to dehydration and hypotension.

- Convalescent phase: recovery lasts weeks to months, and renal function typically recovers.

Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome

- Initial symptoms of Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome (HCPS) include headache, myalgia, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

- Within days, respiratory compromise develops: dyspnea, pulmonary edema, hypotension, and shock; mechanical ventilation is often required.

- Overlapping HFRS features may include thrombocytopenia, petechiae, hematuria, and oliguria.

Etiology

Rodents are the primary reservoirs, though bats, moles, shrews, reptiles, and fish may also carry hantaviruses. Rodents shed virus in saliva, urine, and feces; humans are infected mainly by inhaling aerosolized excreta or, rarely, via rodent bites.[1] Person-to-person transmission has been documented for Andes virus.[7]

Pathophysiology

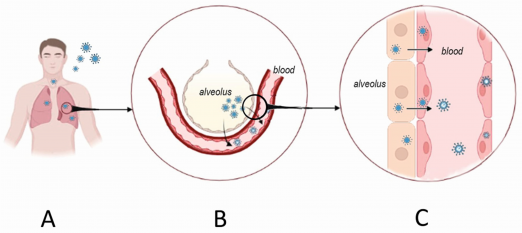

Hantaviruses enter endothelial cells by binding β3 integrins, highly expressed in pulmonary and renal microvasculature. Normally, β3 integrins regulate endothelial responses to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Viral binding disrupts this regulation, causing exaggerated VEGF sensitivity and increased vascular permeability.[8] Infected cells also show heightened activity of Factor XII and kallikrein with elevated bradykinin production, further promoting vasodilation and leakage.[9] Immune activation contributes additional injury: CD8⁺ T cells release cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ, which destabilize endothelial junctions.[10] These mechanisms underlie the pulmonary and renal manifestations of both HFRS and HCPS (Figure 3).

Hantaviruses also disrupt platelet function. Viral binding to platelets via β3 integrins promotes their sequestration and reduces circulating counts, while infected endothelium becomes hyperadhesive, causing platelets to coat vessel walls. Together, these changes impair hemostasis and contribute to mucosal bleeding, ecchymoses, and coagulopathy.[11] Similar permeability mechanisms in the eye allow plasma to leak from ocular microvasculature, explaining eyelid edema, subconjunctival hemorrhage, and elevated intraocular pressure.

Ocular Manifestations

Although the systemic manifestations of hantavirus infection are well described, its ocular effects are less commonly recognized. Yet multiple studies indicate that ophthalmic findings such as blurred vision and periorbital pain are frequent, especially in milder cases of HFRS, known as nephropathia epidemica (NE). Understanding these ocular manifestations is thus important for clinicians who may encounter visual symptoms of varying severity during outbreaks.

Myopia

- Reversible myopia is the most common ocular finding, affecting up to 78% of patients.[12][13][14]

- Refractive changes are usually bilateral and correlate with anterior-segment alterations, most commonly lens thickening (reported in > 80% of cases),[13][14] and anterior chamber shallowing.[14]

- Diagnosis: reduced uncorrected distance visual acuity and a cycloplegic autorefraction of -0.50 diopter or lower.[15]

- Visual acuity doesn’t always worsen; hyperopic patients may temporarily see better.[14]

- All NE-associated myopic changes are transient, with refraction and anatomy returning to baseline as the illness resolves.[14]

Intraocular Pressure (IOP) Changes

Reports on intraocular pressure (IOP) in NE are mixed:

- IOP elevation:

- Some studies describe acute angle-closure glaucoma during infection.[16][17]

- Proposed mechanisms include ciliary body edema or hemorrhage, anterior uveitis, and zonular relaxation with forward lens shift.[18][19]

- Elevated IOP are usually self-resolving, although one case detailed a 32-year-old patient who developed bilateral IOP elevation with choroidal effusion on anterior segment optical coherence tomography and ultrasound biomicroscopy; the effusion resolved following a week of anti-glaucoma and cycloplegic therapy.[17]

- IOP reduction:

- Clinical Approach:

- Clinicians should monitor both hypotony and pressure spikes using serial tonometry.

- If treatment is required for elevated IOP, prostaglandin analogs are first-line agents.[20]

Eyelid Edema and Ocular Surface Findings

- Ocular findings that may be seen without specialized imaging include eyelid swelling, conjunctival chemosis, hyperemia, and subconjunctival hemorrhages (Figure 4).[12][13][18][21]

- Chemosis is especially common, reported in up to 87% of affected eyes.[14]

- Mechanism: hantavirus-induced endothelial dysfunction, leading to increased capillary permeability, and consequently, plasma leakage and red blood cell extravasation.

- These changes reflect transient shifts in vascular integrity rather than direct structural injury to ocular tissues. Thus, they typically resolve as the infection enters recovery.

Uveitis-like Presentation

- Uveitis as an ocular finding in NE is controversial.

- Two case series reported 11 total cases of anterior uveitis that resolved without treatment.[13][18]

- In contrast, a prospective study of 92 eyes found no cases of anterior or posterior uveitis.[14]

- Some reported “uveitis” may reflect transient ciliary body vascular leakage rather than true uveal inflammation. Spontaneous resolution without treatment supports a non-inflammatory mechanism.

Retinal Findings

- Retinal involvement in hantavirus infection is rare but includes:

- Unilateral retinal edema with hemorrhages (1 of 37 patients in one cohort).[13]

- Macular dot-blot hemorrhages and peripapillary streak hemorrhages, likely related to thrombocytopenia.[22]

- Self-limiting posterior necrotizing retinitis with retinal vasculitis. Fundus exam shows:

- Confluent retinal whitening around the optic disc.

- Flame-shaped and patchy retinal hemorrhages.

- Venous sheathing.[23]

General Evaluation

While ocular complications may occur, they are less common than systemic manifestations. Nevertheless, recognition of ocular findings associated with hantavirus infection may facilitate timely diagnosis and coordinated management with other medical specialties, particularly in patients in whom ocular manifestations may precede systemic symptoms.

Early recognition may help reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with hantavirus infection and systemic dissemination. Accordingly, ophthalmologists who suspect hantavirus infection should strongly consider the following general diagnostic evaluations, in addition to appropriate management of ocular specific complications discussed in this article. Such strategies may reduce the overall systemic disease burden and, in turn, potentially mitigate ocular morbidity as well.

Diagnosis

- Gold standard test: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for hantavirus IgM or IgG.

Laboratory Tests

- Complete blood count (CBC): often shows thrombocytopenia and leukocytosis.

- Coagulation studies: prolonged PT/aPTT, prolonged bleeding time, elevated fibrin-degradation products, and decreased fibrinogen.

- Renal & metabolic labs: elevated serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN).

- Urinalysis: presence of proteinuria or hematuria.

Imaging

- Chest X-ray may reveal pulmonary infiltrates, edema, and pleural effusions.

- Renal imaging (ultrasound, CT, MRI) may reveal hydronephrosis or bleeding in the kidneys.

General Treatment

Supportive Care

All suspected hantavirus patients with systemic manifestations should be admitted inpatient to the hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) for close hemodynamic and respiratory monitoring as early recognition of shock or respiratory failure is critical.[24][25]

Fluid Management and Hemodynamic Support

- Correct hypovolemia during the hypotensive phase while avoiding fluid overload (particularly important in HPS where pulmonary edema risk is high). Vasopressors are indicated for persistent hypotension despite fluids.[25]

- If patient has fluid overload or has oliguria, diuretics are recommended.[25]

- Inotropic agents such as dobutamine are recommended early on to maintain cardiac output and blood pressure.[26]

Respiratory Support

- Treat hypoxemia and respiratory failure in HPS. Patients have an 80% survival rate when provided early extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.[24]

- If patients are not appropriately managed with fluids, they tend to require mechanical ventilation.[26]

Corticosteroids

- While no clinical trials have evaluated the use of corticosteroids in treating hantavirus infections, it has been proposed that corticosteroids could improve symptoms given that the pathophysiology of hantavirus largely involves immune system overactivation.[25]

Antiviral Therapy

- Intravenous ribavirin has shown benefit in decreasing viral load in HFRS when given early in the disease course. Its efficacy decreases as the disease course progresses. Evidence for its use in HCPS, however, is lacking.[24]

Management of Coagulopathy

- While there are no guidelines for coagulopathy and bleeding management in the context of hantavirus infection specifically, some general guidelines suggest platelet transfusions to maintain platelet counts above 50 × 10⁹/L in most bleeding situations, and above 15-20 × 10⁹/L if patient is not bleeding but has an infection.[27]

Broad Spectrum Antibiotics

- While antibiotics are not indicated for confirmed hantavirus infections, it is recommended that patients should be given empiric antibiotics if bacterial infections are in the differential while diagnostic tests are pending.[24]

Ocular-directed Management

Most reported hantavirus-associated ocular findings are transient and self-limited, often resolving with supportive care and close observation. Nevertheless, select presentations may warrant targeted ophthalmic intervention based on the underlying mechanism and severity of ocular involvement.

- Persistent IOP elevation: Sustained IOP elevation is uncommon in hantavirus infection and, when reported, is typically secondary to transient anatomic or inflammatory changes rather than primary glaucomatous disease. In patients who develop persistent IOP elevation, management should follow established principles for secondary ocular hypertension rather than hantavirus-specific treatment recommendations.

- Prostaglandin analogs, such as latanoprost, are commonly used first-line agents for chronic IOP elevation in general ophthalmic practice; however, therapy should be individualized based on the suspected mechanism of IOP elevation and the presence of active intraocular inflammation. In cases associated with active uveitis or secondary angle closure, initial use of aqueous suppressants and control of inflammation may be preferred.[20]

- Anterior uveitis or uveitis-like presentations: Although it remains unclear whether hantavirus directly causes anterior uveitis or produces inflammatory findings that mimic uveitis, anterior chamber inflammation has been described in association with infection. If true anterior uveitis is confirmed on slit-lamp examination, topical corticosteroids and cycloplegic agents may be considered for clinically significant inflammation, with careful monitoring for IOP changes. Treatment decisions should be guided by the severity of inflammation and overall systemic status.[28][29]

- Refractive and anterior segment changes: Transient myopic shifts, anterior chamber shallowing, and lens or ciliary body changes have been reported and generally resolve without intervention. These findings typically require reassurance and observation rather than active treatment, unless associated with secondary complications such as angle narrowing or symptomatic IOP elevation.

While most reports suggest that ocular-specific interventions are rarely required, ophthalmologists play an important role in recognizing potential ocular manifestations of hantavirus infection. Close coordination with other specialties, particularly infectious disease and nephrology, is recommended to ensure optimal systemic management, which may in turn also reduce the risk of ocular morbidity.

Follow-Up Care

Early involvement of multidisciplinary teams, including intensive care, infectious disease, nephrology (for HFRS), pulmonology or critical care (for HCPS), and ophthalmology for visual complaints, facilitates coordinated multi-organ management during the acute phase of illness.

As mentioned above, for patients with ocular involvement, long-term follow-up should be guided by the specific clinical findings and severity of presentation:

- Intraocular pressure monitoring: Patients with elevated or fluctuating intraocular pressure should undergo repeat tonometry during the acute illness and convalescent phase to confirm normalization, as IOP changes are often transient. Persistent elevation warrants continued long-term surveillance and management according to secondary ocular hypertension protocols.

- Refractive changes and visual acuity: Patients experiencing acute myopic shifts or blurred vision should have visual acuity reassessed after systemic stabilization. Cycloplegic autorefraction may be helpful to document resolution of transient refractive changes and to distinguish accommodative effects from true biometric alterations.

- Anterior segment evaluation: Slit-lamp examination should be repeated in patients with ocular discomfort, photophobia, or suspected inflammation to assess for anterior chamber cells or flare. Although true uveitis is uncommon, repeat examination may be warranted in symptomatic patients or those receiving topical anti-inflammatory therapy.

- Posterior segment surveillance: In rare cases with reported retinal findings such as edema, hemorrhage, or retinitis, serial dilated fundus examinations should be performed to monitor resolution and detect potential complications. Optical coherence tomography may be considered when retinal edema is suspected or visual symptoms persist.

Overall, most ocular findings resolve without long-term sequelae; however, short-term ophthalmic follow-up is prudent to document resolution and exclude uncommon but potentially vision-threatening complications.

Vaccination and Prevention

Although no vaccines against hantavirus are currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the World Health Organization, inactivated Orthohantavirus vaccines have been developed and deployed in China and South Korea. These vaccines have demonstrated a favorable safety profile and evidence of protective effectiveness in endemic populations, though robust large-scale, randomized data remain limited, and long-term durability of protection is still being evaluated. Potential future preventive strategies include DNA-based vaccines targeting viral subunit antigens, which are under active preclinical and early clinical investigation.[25]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Vial PA, Ferrés M, Vial C, et al. Hantavirus in humans: a review of clinical aspects and management. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2023;23(9):e371-e382. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00128-7

- ↑ Jeyachandran AV, Irudayam JI, Dubey S, et al. Differential tropisms of old and new world hantaviruses influence virulence and developing host-directed antiviral candidates. PLoS Pathog. 2025;21(8):e1013401. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1013401

- ↑ CDC. Reported Cases of Hantavirus Disease. Hantavirus. Published June 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/data-research/cases/index.html

- ↑ Kim WK, Cho S, Lee SH, et al. Genomic Epidemiology and Active Surveillance to Investigate Outbreaks of Hantaviruses. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;10:532388. Published 2021 Jan 8. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.532388

- ↑ Avšič-Županc T, Saksida A, Korva M. Hantavirus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;21S:e6-e16. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12291

- ↑ Jiang H, Du H, Wang LM, Wang PZ, Bai XF. Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome: Pathogenesis and Clinical Picture. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:1. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2016.00001

- ↑ Watson DC, Sargianou M, Papa A, Chra P, Starakis I, Panos G. Epidemiology of Hantavirus infections in humans: A comprehensive, global overview. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2014;40(3):261-272. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2013.783555

- ↑ Gavrilovskaya IN, Gorbunova EE, Mackow NA, Mackow ER. Hantaviruses Direct Endothelial Cell Permeability by Sensitizing Cells to the Vascular Permeability Factor VEGF, while Angiopoietin 1 and Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Inhibit Hantavirus-Directed Permeability. J Virol. 2008;82(12):5797-5806. doi:10.1128/JVI.02397-07

- ↑ Taylor SL, Wahl-Jensen V, Copeland AM, Jahrling PB, Schmaljohn CS. Endothelial cell permeability during hantavirus infection involves factor XII-dependent increased activation of the kallikrein-kinin system. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(7):e1003470. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003470

- ↑ Terajima M, Ennis FA. T Cells and Pathogenesis of Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome and Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome. Viruses. 2011;3(7):1059-1073. doi:10.3390/v3071059

- ↑ Gavrilovskaya IN, Gorbunova EE, Mackow ER. Pathogenic hantaviruses direct the adherence of quiescent platelets to infected endothelial cells. J Virol. 2010;84(9):4832-4839. doi:10.1128/JVI.02405-09

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Saari KM, Luoto S. Ophthalmological findings in nephropathia epidemica in Lapland. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1984;62(2):235-243. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1984.tb08400.x

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Kontkanen M, Puustjärvi T, Kauppi P, Lähdevirta J. Ocular characteristics in nephropathia epidemica or Puumala virus infection. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1996;74(6):621-625. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.1996.tb00748.x

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 Hautala N, Kauma H, Vapalahti O, et al. Prospective study on ocular findings in acute Puumala hantavirus infection in hospitalised patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(4):559-562. doi:10.1136/bjo.2010.185413

- ↑ Modjtahedi BS, Abbott RL, Fong DS, et al. Reducing the Global Burden of Myopia by Delaying the Onset of Myopia and Reducing Myopic Progression in Children: The Academy’s Task Force on Myopia. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(6):816-826. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.10.040

- ↑ Saari M, Alanko H, Järvi J, Vetoniemi-Korhonen SL, Räsänen O. Nephropathia Epidemica: The Scandinavian Form of Hemorrhagic Fever With Renal Syndrome. JAMA. 1977;238(8):874-877. doi:10.1001/jama.1977.03280090038018

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Baillieul A, Le TL, Rouland JF. Acute angle-closure glaucoma with choroidal effusion revealing a hantavirus infection: Description of ultrasound biomicroscopy imagery and optical coherence tomography Visante. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021;31(1):NP4-NP8. doi:10.1177/1120672119858895

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Saari KM. Acute Glaucoma in Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome (Nephropathia Epidemica). American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1976;81(4):455-461. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(76)90301-9

- ↑ Zimmermann A, Lorenz B, Schmidt W. [Bilateral acute angle-closure glaucoma due to an infection with Hantavirus]. Ophthalmologe. 2011;108(8):753-758. doi:10.1007/s00347-010-2311-8

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Gedde SJ, Vinod K, Wright MM, et al. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(1):P71-P150. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.10.022

- ↑ Kontkanen M, Puustjärvi T. Hemorrhagic fever (Puumala virus infection) with ocular involvement. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1998;236(9):713-716. doi:10.1007/s004170050146

- ↑ Mehta S, Jiandani P. Ocular features of hantavirus infection. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55(5):378-380. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.33827

- ↑ Cao Y, Zhao X, Yi J, Tang R, Lei S. Hantavirus retinitis and concurrent hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017;52(1):e41-e44. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.09.017

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 CDC. Clinician Brief: Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS). Hantavirus. March 13, 2025. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/hcp/clinical-overview/hps.html

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Romero MG, Rout P, Hashmi MF, Anjum F. Hemorrhagic Fever Renal Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed November 27, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560660/

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Moore RA, Griffen D. Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed November 27, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513243/

- ↑ Platelet transfusion: Indications, ordering, and associated risks - UpToDate. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/platelet-transfusion-indications-ordering-and-associated-risks#H558395184

- ↑ Maghsoudlou P, Epps SJ, Guly CM, Dick AD. Uveitis in Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2025;334(5):419-434. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.4358

- ↑ Angulo MI, Barajas M, Vela M. What Is Uveitis? JAMA. Published online October 30, 2025. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.16917