Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy does not have a designated code per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature; however, it can be classified as ICD-10 H35.89 (Other specified retinal disorders).

Disease

Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy (AEPVM) is a rare retinal disorder characterized by bilateral multifocal yellow-white subretinal lesions that correspond to serous retinal detachments. It was first described by Gass, et al. in 1988, after which several case series and reports have been published.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Etiology

The etiology of AEPVM is poorly understood, but it is believed to be an autoimmune-mediated retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) dysfunction leading to lipofuscin accumulation and secondary exudative retinal detachments.[1][5][6][7][8][9] It is separated into two forms based on the underlying mechanism: idiopathic and paraneoplastic.

- Idiopathic AEPVM. Idiopathic AEPVM is often associated with antecedent trauma, infectious disease (hepatitis C, Coxsackie B, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, COVID-19, syphilis, herpes zoster, Lyme disease), or idiopathic processes.[6][10][11][12][13][14] These agents are hypothesized to precipitate an immune reaction that targets the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and/or photoreceptor proteins via activation of inflammatory cells or cross-reaction with pathogenic antigens.[8][10][15]

- Paraneoplastic AEPVM. AEPVM can also manifest as a paraneoplastic process. It is seen most commonly in patients with cutaneous and choroidal melanoma, although carcinomas of the breast, lung, and colon have been documented in a few cases.[16][17][18][19] Symptoms often emerge following the initiation of BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) or PD-1 inhibitors (pembrolizumab, nivolumab), but whether the condition is tumor-induced, drug-induced, or a combination of both remains unclear.[6][7][20][21] The proposed mechanism is similar to idiopathic AEPVM: immune system activation and development of autoantibodies against the RPE and/or photoreceptor proteins. Putative antigens include recoverin, transducin-⍺, peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3), carbonic anhydrase 2 (CA2), a 120 kDa photoreceptor protein, and a 145 kDa interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein.[6][10][22]

Epidemiology

AEPVM was initially described in young males but has since been recognized in older patients and females.[2][10] Although it predominantly affects Caucasian individuals, a few cases have been documented in Hispanic, Black, and Native American populations.[1][14][23] Paraneoplastic AEPVM occurs in the context of malignancy and is therefore typically seen in older adults.[24]

Pathophysiology

The yellow-white lesions characteristic of AEPVM represent the deposition of vitelliform material and the accumulation of subretinal fluid (SRF), leading to retinal detachments. It is postulated that autoimmune-mediated RPE dysfunction results in lipofuscin-rich exudate that comprises the lesions.[2][5][9][25] Other theories posit that the material is composed of shed photoreceptor outer segments, cellular debris, or fluorophores, either in addition to or instead of lipofuscin.[1][5][14]

Clinical Features

History

Idiopathic AEPVM may be accompanied by a history of recent viral prodrome, bacterial infection, HIV, syphilis, or trauma.[6][10][11][12][13][14] A typical history for paraneoplastic AEPVM includes melanoma (cutaneous, choroidal) or carcinoma (lung, breast, colon) and BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) or PD-1 inhibitor (pembrolizumab, nivolumab) therapy.[16][17][18][19] AEPVM may also present in an otherwise healthy patient with no significant history, either as an idiopathic process or the initial manifestation of an occult primary neoplasm.[26]

Physical Examination

Examination of the fundus is performed using indirect ophthalmoscopy and slit-lamp biomicroscopy with appropriate lenses.

Signs

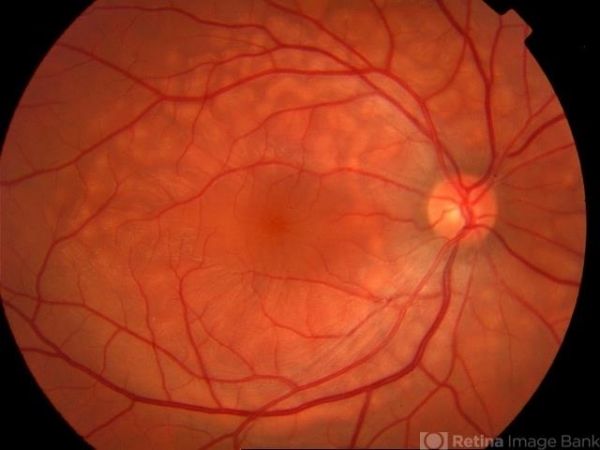

The fundoscopic hallmark of AEPVM is the presence of symmetric, bilateral, multifocal, yellow-white subretinal lesions of varying morphology (round, oval, curvilinear) which are located predominantly in the macular region and correspond to serous retinal detachments on OCT.[2][8][27] In a subset of patients, these lesions may also be found in a honeycomb-like pattern along the major retinal vascular arcades and tend to have a bleb-like appearance.[1][8]

Symptoms

Patients often present with bilateral central blurred vision and/or vision loss. Acute-onset headaches is a frequent complaint among patients with idiopathic AEPVM.[1][2]

Disease Progression

There are two stages of AEPVM:

- acute and

- convalescent.

The acute stage is characterized by the fundoscopic findings described above and may involve the formation of a large vitelliform retinal detachment that resembles a pseudohypopyon. During the convalescent stage, central visual acuity typically improves as the subretinal fluid resolves first, leaving behind vitelliform material that precipitates and gravitates in the form of a meniscus in the inferior macular region. These yellow polymorphous deposits can be asymmetric and may resolve completely or persist for years.[1][8][16][25][28]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of this disease is primarily clinical and relies on characteristic multimodal imaging findings, including Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF), and Fluorescein Angiography (FA).

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

The vitelliform lesions seen on fundoscopy in the acute stage correspond to neurosensory retinal detachments with subretinal fluid and hyperreflective subretinal deposits on spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT). The macular retinal detachments are large and dome-shaped, while the honeycomb-pattern detachments along the vascular arcades, if present, tend to be smaller and show subretinal fluid in a wave-like distribution. A thick layer of hyperreflective material representing the vitelliform deposits is present on the outer retinal surface of the detachments.[1][29]

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) in the convalescent stage reveals resolution of the serous fluid and reattachment of the retina to the RPE. The hyperreflective deposits that remain migrate towards the inferior aspects of the lesions.[1]

Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF)

In the acute stage, the serous fluid is not autofluorescent and the vitelliform material is hyperautofluorescent. The hyperautofluorescent deposits shift towards the inferior aspect of the detachments forming a pseudohypopyon and potentially resolve in the recovery stage.[1][20][30]

Fluorescein Angiography (FA)

The serous fluid in the acute stage exhibits faint early hyperfluorescence on FA, while the vitelliform material tends to be hypo- or nonfluorescent. There are no signs of contrast leakage or hot disc.[1][20][26][31]

In the convalescent stage, as the fluid resolves and only the deposits remain, the lesions appear nonfluorescent.[25] FA and FAF represent inverted images in AEPVM, as the hyperautofluorescent vitelliform material seen on FAF masks choroidal fluorescence in FA.[1]

Visual Electrophysiology

Electrooculogram (EOG) may be normal or abnormal, with a decreased Arden ratio indicating RPE dysfunction.[2][15][29] Electroretinogram (ERG) may also demonstrate abnormalities suggestive of photoreceptor dysfunction, such as reduced amplitudes.[11] These electrophysiologic findings can appear in the acute phase and may persist throughout the recovery phase and beyond.[5][32]

Laboratory Tests

Because paraneoplastic AEPVM may present prior to discovery of the associated primary neoplasm, a complete work-up to exclude systemic malignancy is indicated for patients with a negative oncologic history who present with AEPVM.[4]

All AEPVM patients tested for mutations in BEST1 and peripherin/RDS genes have been negative, rendering genetic testing a valuable diagnostic tool to exclude similarly presenting diseases (see Differential Diagnosis below).[1]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of AEPVM may include:

- Best vitelliform macular dystrophy,

- adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy,

- atypical presentation of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease, and

- the ocular-CNS form of large cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL): primary vitreoretinal lymphoma.

Genetic testing for mutations in the BEST1 or peripherin/RDS genes can exclude the bestrophinopathies; vitelliform lesions on fundoscopy and an absence of hot disc on FA are inconsistent with VKH disease; the multifocal yellow subretinal lesions with serous macular detachments seen in large cell NHL tend to be asymmetric and more closely resemble fundus flavimaculatus than AEPVM.[1][8][23][25][33]

Management

AEPVM is considered a self-limiting condition, as its natural course is spontaneous resolution of the serous fluid with associated restoration of central visual function over several months.[13][34] In some cases, it may recur years after onset or develop into a chronic illness with slow visual recovery, if at all.[28]

Medical therapy

Medical therapy is not indicated as AEPVM resolves on its own over the course of several months. Discontinuation of PD-1 or BRAF inhibitor therapy in the paraneoplastic form is controversial, as some studies report resolution and others find no improvement upon medication cessation.[6][20][21] Treatment of the primary neoplasm with alternative immune therapy agents can be considered in these cases.[21][34]

Medical follow up

Close observation with serial fundus examination and OCT is recommended.[14][34]

Prognosis

Prognosis for AEPVM is favorable, as most patients recover to normal or near-normal visual acuity.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Barbazetto I, Dansingani KK, Dolz-Marco R, et al. Idiopathic Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy: Clinical Spectrum and Multimodal Imaging Characteristics. Ophthalmology. Jan 2018;125(1):75-88. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.07.020

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Gass JD, Chuang EL, Granek H. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1988;86:354-66.

- ↑ Grenga PL, Fragiotta S, Cutini A, Vingolo EM. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy: To bolus or not to bolus? Oman J Ophthalmol. Sep-Dec 2018;11(3):280-283. doi:10.4103/ojo.OJO_12_2017

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Grunwald L, Kligman BE, Shields CL. Acute exudative polymorphous paraneoplastic vitelliform maculopathy in a patient with carcinoma, not melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. Aug 2011;129(8):1104-6. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.215

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Koreen L, He SX, Johnson MW, Hackel RE, Khan NW, Heckenlively JR. Anti-retinal pigment epithelium antibodies in acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy: a new hypothesis about disease pathogenesis. Arch Ophthalmol. Jan 2011;129(1):23-9. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.316

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Sandhu HS, Kolomeyer AM, Lau MK, et al. Acute Exudative Paraneoplastic Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy during Vemurafenib and Pembrolizumab Treatment for Metastatic Melanoma. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Spring 2019;13(2):103-107. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000604

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lambert I, Fasolino G, Awada G, Kuijpers R, Ten Tusscher M, Neyns B. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy during pembrolizumab treatment for metastatic melanoma: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. Jun 5 2021;21(1):250. doi:10.1186/s12886-021-02011-4

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Van Camp S, Vande Walle S, Casteels I, et al. Acute bilateral serous retinal detachments with spontaneous resolution in a 6-year-old boy. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2020;10:Doc37. doi:10.3205/oc000164

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Yung M, Klufas MA, Sarraf D. Clinical applications of fundus autofluorescence in retinal disease. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2016;2:12. doi:10.1186/s40942-016-0035-x

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Dalvin LA, Johnson AA, Pulido JS, Dhaliwal R, Marmorstein AD. Nonantibestrophin Anti-RPE Antibodies in Paraneoplastic Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy. Transl Vis Sci Technol. May 2015;4(3):2. doi:10.1167/tvst.4.3.2

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Gameiro Filho AR, Sturzeneker G, Rodriguez EEC, Maia A, Morales MC, Belfort RN. Acute exudative polymorphous paraneoplastic vitelliform maculopathy (AEPPVM) associated with choroidal melanoma. Int J Retina Vitreous. Apr 1 2021;7(1):27. doi:10.1186/s40942-021-00300-0

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lentzsch AM, Dooling V, Wegner I, et al. Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy Associated with Primary Epstein-Barr Virus Infection. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Nov 1 2022;16(6):740-746. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000001066

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Osman M, Mehana O, Eissa M, Zeineldin S, Sinha A. Coronavirus Disease 2019-induced Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. Oct-Dec 2022;29(4):235-237. doi:10.4103/meajo.meajo_61_23

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Zhang W, Sharma S, Reichstein DA, Fekrat S. Possible Herpetic Viral Association in Cases of Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy. Journal of VitreoRetinal Diseases. 2019;3(1):31-35.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Baddar D, Fayed AE, Tawfik CA, Bassily S, Gergess MM, El-Agha MH. Covid-19 Vaccine-Induced Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy: Case Reports. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Jan 1 2024;18(1):66-70. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000001319

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Al-Dahmash SA, Shields CL, Bianciotto CG, Witkin AJ, Witkin SR, Shields JA. Acute exudative paraneoplastic polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy in five cases. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. Sep-Oct 2012;43(5):366-73. doi:10.3928/15428877-20120712-01

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gao J, Panse K, Foster CS, Anesi SD. Paraneoplastic acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy improved with intravitreal methotrexate. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. Dec 2020;20:100930. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100930

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Gunduz K, Condu G, Shields CL. Acute Exudative Polymorphous Paraneoplastic Vitelliform Maculopathy Managed With Intravitreal Aflibercept. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. Oct 1 2017;48(10):844-850. doi:10.3928/23258160-20170928-11

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Modi KK, Roth DB, Green SN. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy in a young man: a case report. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Summer 2014;8(3):200-4. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000042

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Kemels D, Ten Berge J, Jacob J, Schauwvlieghe PP. The Role of Checkpoint Inhibitors in Paraneoplastic Acute Exudative Polymorphous Vitelliform Maculopathy: Report of Two Cases. Retin Cases Brief Rep. Sep 1 2022;16(5):614-618. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000001040

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Samalia P, Niederer R. Reversible BRAF inhibitor-induced acute exudative paraneoplastic polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. N Z Med J. Aug 13 2021;134(1540):89-92.

- ↑ Mueller CM, Hojjatie SL, Lawson DH, et al. Clinical correlation between acute exudative polymorphous paraneoplastic vitelliform maculopathy and metastatic melanoma disease activity: a 48-month longitudinal case report. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2022;30(2):330-337.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Baxter CR, Abbas A, Lin AL. Multifocal Macular Lesions in a Middle-aged Woman. JAMA Ophthalmol. Apr 1 2022;140(4):428-429. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.4983

- ↑ Singh RS, Tran LH, Kim JE. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy in a patient with Lyme disease. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. Sep-Oct 2013;44(5):493-6. doi:10.3928/23258160-20130909-14

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Chan CK, Gass JD, Lin SG. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy syndrome. Retina. Aug 2003;23(4):453-62. doi:10.1097/00006982-200308000-00002

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Neves GdF, Bastos ALCdM. Acute exsudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy: a case report. Revista Brasileira de Oftalmologia. 2017;76:94-97.

- ↑ Fernandes JS, Gomes PP, Neves P, Marques JP. Idiopathic acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy: the importance of multimodal imaging, systemic workup and genetic testing. BMJ Case Rep. Jun 28 2023;16(6)doi:10.1136/bcr-2022-253969

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Astakhov YS, Astakhov SY, Lisochkina AB, Nechiporenko PA. Eight-year multimodal follow-up of recurrent idiopathic acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. J Fr Ophtalmol. Jun 2020;43(6):500-516. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2020.01.004

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Heng JS, Kim JM, Jones DK, et al. Autoimmune retinopathy with associated anti-retinal antibodies as a potential immune-related adverse event associated with immunotherapy in patients with advanced cutaneous melanoma: case series and systematic review. BMJ open ophthalmology. 2022;7(1):e000889.

- ↑ Lee RM, Robson AG, Hughes EH. Electrooculogram (EOG) findings in a case of acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy (AEPVM) detected following trauma. Doc Ophthalmol. Dec 2013;127(3):255-9. doi:10.1007/s10633-013-9408-8

- ↑ Sommer M, Singer C, Djavid D, Seidel G. Imaging features and functional outcome in a case of idiopathic acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. Dec 2020;20:100870. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100870

- ↑ Kozma P, Locke KG, Wang YZ, Birch DG, Edwards AO. Persistent cone dysfunction in acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. Retina. Jan 2007;27(1):109-13. doi:10.1097/01.iae.0000226537.95346.ca

- ↑ Cruz-Villegas V, Villate N, Knighton RW, Rubsamen P, Davis JL. Optical coherence tomographic findings in acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. Oct 2003;136(4):760-3. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00426-4

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Yu H, Ma X, Tong N, Zhou Z, Zhang Y. Acute exudative paraneoplastic polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy in a patient with thymoma, myasthenia gravis, and polymyositis. Eur J Ophthalmol. May 2022;32(3):NP56-NP61. doi:10.1177/1120672121994042